Cardiovascular problems

Just the facts

Just the factsIn this chapter, you’ll learn:

anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system

diagnostic testing for cardiovascular problems

treatments and procedures for cardiovascular problems

cardiovascular system disorders that occur in children

nursing care for the child with cardiovascular problems.

Anatomy and physiology

Understanding cardiovascular problems in children requires a sound, working knowledge of normal cardiac structure and function.

Structures of the heart

The heart is a muscular organ located behind the sternum in the chest and covered by a sac called the pericardium. Its main purpose is to pump blood throughout the body by continuous rhythmic contractions. The heart is composed of four chambers (two atria and two ventricles) and four valves.

|

Heart chambers

The four chambers of the heart are the right and left atria and the right and left ventricles.

Atria

The atria serve as reservoirs during ventricular contraction (systole) and as pumps during ventricular relaxation (diastole). The

right atrium and left atrium are separated by an atrial septum.

right atrium and left atrium are separated by an atrial septum.

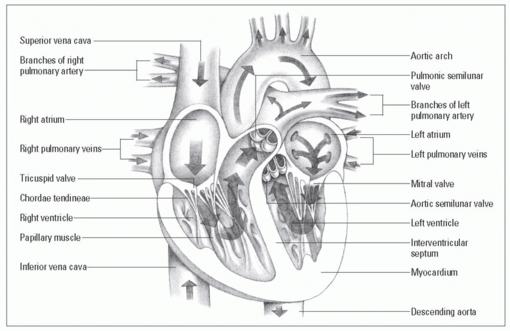

A look inside the heart

Within the heart lie four chambers (two atria and two ventricles) and four valves (two atrioventricular and two semilunar valves). A system of blood vessels carries blood to and from the heart.

|

Ventricles

The left ventricle propels blood through the aorta to the rest of the body. The right ventricle sends blood through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. The ventricles are separated by an

interventricular septum.

Equal at birth

At birth, the ventricles are relatively equal in size because of lowresistance placental circulation. When the left ventricle begins functioning against systemic resistance that increases after birth, however, it becomes thicker than the right ventricle. (See A look inside the heart.)

Heart valves

The heart has four valves:

Tricuspid and mitral valves

The tricuspid and mitral valves are known as the atrioventricular (AV) valves. They prevent blood backflow from the ventricles to the atria during ventricular contraction.

Location, leaflets, and muscles

The tricuspid valve is located between the right atrium and ventricle. It has three leaflets, or cusps, and three papillary muscles. The mitral valve is situated between the left atrium and ventricle. It has two leaflets and two papillary muscles.

Lovely leaflets

The leaflets of both the tricuspid and the mitral valve are attached to the papillary muscles of the ventricles by thin, fibrous bands called chordae tendineae.

Aortic and pulmonic valves

The aortic and pulmonic valves are known as the semilunar valves. These valves prevent backflow of blood from the aorta and pulmonary artery into the ventricles during ventricular relaxation. The aortic valve is located between the left ventricle and the aorta. The pulmonic valve is located between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery.

Circulation

Blood is returned to the heart via the veins. Veins are small, thin-walled blood vessels that carry deoxygenated blood from the capillaries to the heart.

A long day’s journey

Blood enters the right atrium from the inferior and superior vena cavae and then goes into the right ventricle. From there, it’s pumped into the pulmonary artery to the lungs, where it gains oxygen and loses carbon dioxide.

Return to sender

The pulmonary veins bring the oxygenated blood from the lungs to the left atrium. The oxygenated blood then passes into the left ventricle, is pumped into the aorta, and is delivered to the rest of the body via the arteries. Arteries are large, thick-walled blood vessels that distribute oxygenated blood to the capillaries.

Pulmonary role reversal

The pulmonary artery is the only artery in the body that carries deoxygenated blood. The pulmonary veins are the only veins in the body that carry oxygenated blood.

Conduction system

The heart’s conduction system is an electrical system that initiates myocardial contractions to move blood through the heart and maintain its rhythmic pumping action. This system is composed of several specialized cells:

The sinoatrial node (also called the pacemaker of the heart) is located within the right atrial wall near the opening of the superior vena cava. It initiates electrical impulses and sends them throughout the atria.

The AV node is located within the right atrium near the lower end of the septum. It transmits impulses from the atria to the ventricle.

|

Bundles and branches

The AV bundle (bundle of His) extends from the AV node to each side of the interventricular septum and divides into right and left bundle branches. It facilitates rapid conduction of the impulses through the ventricles.

The Purkinje fibers extend from the AV bundle into the walls of the ventricles and rapidly conduct impulses through the heart muscle.

Cardiac physiology

The heart’s primary purpose is to pump the blood that delivers oxygen and nutrients to tissues throughout the body and to remove waste products such as carbon dioxide. To do this, the heart must maintain an adequate cardiac output.

Cardiac output is the amount of blood ejected by the heart in 1 minute. Cardiac output can be determined by multiplying the heart rate in 1 minute by the stroke volume. Stroke volume

is the amount of blood ejected by the heart at each heartbeat (or contraction).

is the amount of blood ejected by the heart at each heartbeat (or contraction).

Stroke volume is affected by three factors:

Afterload is the resistance against which the ventricle must pump during its contraction, which can be affected by blood pressure. (Hypertension will increase afterload, as the heart must pump harder to force blood into circulation.)

Afterload is the resistance against which the ventricle must pump during its contraction, which can be affected by blood pressure. (Hypertension will increase afterload, as the heart must pump harder to force blood into circulation.)Chillin’ with homeostasis

To maintain homeostasis, the body will make many adjustments to the factors that contribute to cardiac output.

Cardiac adaptations at birth

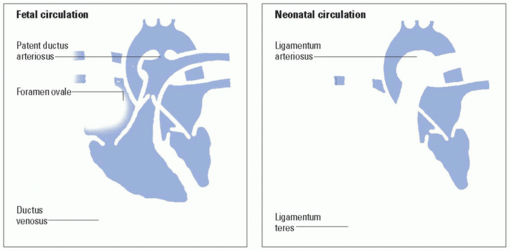

During fetal circulation, blood is oxygenated and waste products are removed in the placenta. Blood is shunted away from those organs that aren’t yet fully functional, such as the lungs and the liver.

|

Perfusion only—no exchange

In the fetus, the lungs are filled with fluid and aren’t yet the site of gas exchange. The amount of blood that passes through the lungs is just enough to perfuse lung tissue.

Farewell placenta, hello lungs!

At birth, however, the neonate must transition from a reliance on the placenta to a reliance on his lungs for oxygenation. This transition is normally accomplished within the first few breaths after birth.

Many keys, one lock

Key structures that maintain fetal circulation include:

umbilical vein, which carries oxygenated blood from the placenta to the fetus

umbilical arteries, which carry deoxygenated blood from the fetus to the placenta

foramen ovale, which serves as the septal opening between the atria of the fetal heart

ductus arteriosus, which connects the pulmonary artery to the aorta, allowing blood to bypass the fetal lungs

ductus venosus, which carries oxygenated blood from the umbilical vein to the inferior vena cava (IVC), bypassing the liver.

Out with fluid, in with air

Cardiac adaptations at birth occur gradually, resulting from structural and pressure changes in the lungs, heart, and major vessels. With the first few breaths after birth, the fluid in the neonate’s lungs is absorbed and replaced with air. Inspired oxygen dilates the pulmonary vessels, resulting in decreased pulmonary vascular resistance and increased pulmonary blood flow as the lungs fill with air and expand. More blood will now travel to and from the lungs.

|

The drama unfolds

The pressure in the right atrium, right ventricle, and pulmonary artery decreases. Simultaneously, a gradual increase in systemic vascular resistance occurs when the umbilical cord is clamped and the low-resistance placental circulation is removed. At that point, left atrial pressure increases more than right atrial pressure. The foramen ovale, which was a one-way door, closes as a result of this unequal pressure. The ductus arteriosus begins to close because of increased pulmonary blood flow and the dramatic reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance. Later, the ductus arteriosus (and ductus venosus) will become ligaments and will be closed structurally.

Out of a job

Function of the foramen ovale ceases immediately or soon after birth. Ductus arteriosus functioning ceases after the infant is about 4 days old. Anatomic closure, however, takes considerably longer. If the foramen ovale or ductus arteriosus fails to close, persistent shunting of fetal blood away from lungs will result. (See From fetal to neonatal circulation, page 270.)

Murmurs

Murmurs are produced by vibrations within the chambers of the heart or major arteries from the back-and-forth flowing of blood through these structures. In children, murmurs may be called:

innocent, which means there’s no anatomic or physiologic cause

functional when there’s a physiologic cause, such as anemia, but no anatomic abnormality

organic when there’s some anatomic defect in the heart, with or without the existence of a physiologic abnormality.

From fetal to neonatal circulation

These illustrations show the changes in circulation that occur at birth, allowing all neonatal blood to pass through the lungs.

|

Sit, stand, recline

When auscultating for murmurs, position the child in the sitting and reclining positions. Also, auscultate the heart with the child standing, sitting and leaning forward, and in a left side-lying position. (See Grading murmurs.)

Diagnostic tests

Diagnostic tests of the cardiovascular system in children include:

echocardiography

electrocardiography (ECG)

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is used to evaluate cardiac structures and functions using echoes from pulsed, high-frequency sound waves. An ultrasound transducer is placed on the chest, and the sound waves

produce an image of the heart. The test is noninvasive and painless and is one of the most commonly used tests to detect cardiac problems in children.

produce an image of the heart. The test is noninvasive and painless and is one of the most commonly used tests to detect cardiac problems in children.

Ultrasound-endoscopy combo

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) combines ultrasound with endoscopy. It’s an alternative method for detecting cardiovascular problems in children and is used when the transthoracic approach isn’t possible or would be difficult. During the procedure, the transducer is passed into the esophagus to an area behind the atria. The procedure is more complicated than the transthoracic approach and may require sedation and intubation to preserve the airway in young children.

Nursing considerations

Explain the procedure to the child and his parents; tell the child what he’ll see, hear, and feel and be honest about any pain or discomfort he might experience. In addition, follow these steps:

Stress the importance of holding still during the test and assist as necessary. (Tell the child that holding still is his “very important job.”)

Administer mild sedation if needed. Use distractions such as a videotape to help calm the child.

For TEE, administer sedation as ordered and assist with endotracheal intubation as necessary. Explain that the child must have nothing to eat or drink before the procedure.

Electrocardiography

ECG provides a graphic representation of the heart’s electrical activity. It’s used to detect the presence of ischemia, injury, necrosis, bundle-branch block, fascicular blocks, conduction delay, chamber enlargement, and arrhythmias.

Nursing considerations

Explain the test to the child and his parents, stressing that there’s no pain involved. In addition:

Describe the equipment that will be used for the test; show the child a picture or, if possible, the actual equipment.

Explain that the child may have to lie on his left side, inhale and exhale slowly, or hold his breath at intervals during the test.

Encourage the child to be still during the test; he may sit on his parent’s lap if necessary.

Grading murmurs

Use the system outlined here to describe the intensity of a murmur. When recording your findings, use Roman numerals as part of a fraction, always with “VI” as the denominator. For example, a grade III murmur would be recorded as “grade III/VI.”

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI uses magnetic fields and radio frequencies to show a crosssectional view of the heart and its structures. It’s useful in identifying some congenital heart defects. MRI is generally a noninvasive test; however, contrast media may be used.

Nursing considerations

When explaining the test to the child, show him a picture of the scanner or, whenever possible, let the child see the actual scanner. Tell the child that no pain is involved; prepare him if contrast media must be used. In addition:

Tell the child that his parents may stay in the room with him during the scan.

Prepare the child for the movements and the loud, clicking noises made by the scanner; reassure him that the machine won’t touch him.

Because no metal can go in the scanner, assist the child in removing hair clips, jewelry, and other metal items as necessary.

If necessary, provide sedation to ensure that the child remains still during the test.

Assess for a history of iodine or seafood allergies before the procedure if a contrast medium is to be used.

Exercise testing

Exercise testing may be done for some children, depending on their age and general condition. With it, the child’s doctor can evaluate the extent of disease from any heart or lung disease that may be present. In addition, it can help to determine what kinds of activity ease or aggravate the child’s condition, as well as his or her conditioning, both aerobic and musculoskeletal. Either a treadmill or a stationary bike may be used while the child’s heart and respiratory rate are monitored. The blood pressure and pulse oximetry are also monitored during the exercise test.

Nursing considerations

Most children know what a bicycle looks like, but they may not be familiar with the concept of a stationary bike. They may not recognize a treadmill at all. So, good instructions and explanations may be necessary. Pictures or other visual aids may be helpful. Let the child know that there will be monitoring equipment, which may contain several wires that may be attached to him or her. Assure the child that there is no pain involved. In addition:

The child’s parents may remain in the room with the child, unless the child prefers to test alone (a possibility for an older school-age child or an adolescent).

Be sure the child knows that the doctor needs to be notified right away if there is any discomfort, or if there is any difficulty keeping up with the exercise.

Treatments and procedures

Treatments and procedures used for cardiac problems in childhood include:

valve replacement

cardiac catheterization

cardiac surgery

cardiac transplantation.

Teach expectations

Many of the treatments and procedures done for children with cardiac problems involve surgery. When a child knows what to expect before a surgical procedure, he’ll be less frightened, more cooperative, and more trusting of the nurses who provide his care. (See Preparing children for surgery, page 274.)

Valve replacement

Valve replacement with a prosthetic valve is indicated for heart valve narrowing (stenosis) and heart valve leaking (insufficiency). Valvular problems are commonly caused by rheumatic fever and congenital heart defects. They may also be caused by heart failure and infective endocarditis.

Nursing considerations

Nursing interventions focus on monitoring and educating the patient and his parents.

After surgery, monitor for hypotension, arrhythmias, and thrombus formation.

Monitor vital signs, arterial blood gas (ABG) values, intake, output, daily weight, blood chemistries, chest X-rays, and pulmonary artery catheter readings.

Heed the signs

• Because lifelong anticoagulant therapy will be necessary, teach the parents (and the child, if old enough) to recognize the signs and symptoms of bleeding, including black, tarry stools (from GI bleeding); oral bleeding (a small, soft bristle toothbrush should be used to prevent this); and excessive bleeding from minor cuts and scrapes.

Preparing children for surgery

Many of the interventions performed for cardiac problems involve major surgery. What a child imagines about surgery is likely much more frightening than the reality. A child who knows what to expect ahead of time will be less fearful and more cooperative and will learn to trust his caregivers. A child who’s well prepared for medical procedures is much less likely to experience emotional trauma, which can have longlasting effects.

Developmental concerns

Many of the concerns that children may have about hospitalization and surgery relate to their particular stage of development.

Infants, toddlers, and preschoolers

Infants and toddlers are most concerned about separation from their parents. Stranger anxiety may make a necessary separation (during surgery) especially difficult.

Because toddlers think concretely, showing is a necessary adjunct to telling when preparing a toddler for surgery.

Preschoolers may view medical procedures, including surgeries, as punishments for some type of perceived bad behavior.

Preschoolers are also likely to have many misconceptions about what will happen during surgery.

School-age children

School-age children have concerns about fitting in with peers and may view surgery as something that sets them apart from their friends.

A desire to appear “grown up” may make the school-age child reluctant to express his fears.

Because this age is a time when children are especially curious and interested in learning, school-age children are very receptive to preoperative teaching and will likely ask many important questions (although they may need to be given the “permission” to do so).

Adolescents

Adolescents struggle with the conflict between wanting to assert their independence and needing their parents (and other adults) to take care of them during illness and treatment.

Adolescents may want to discuss their illness and treatment without a parent present.

In addition, adolescents may have a hard time admitting that they’re afraid or experiencing pain or discomfort.

Before surgery

Whenever the situation permits, arrange for the child to visit the hospital before he’s admitted for surgery. Ideally, the formal preparation for surgery is done during the preadmission visit.

Explanations should be honest and age-appropriate and should involve the parents (unless the adolescent would rather be prepared alone). The explanation should focus on what the child will see, hear, and feel; where his parents will be waiting for him; and when they’ll be reunited.

If a child will initially be cared for in an intensive care setting, allow him to visit the area ahead of time and to meet some of the nurses who will be caring for him. Prepare him for the equipment and the other patients he’ll see.

Principles of preparation

Here are some principles to keep in mind when preparing a child for surgery:

Begin by asking the child to tell you what he thinks is going to happen during his surgery.

Ask the child about worries or fears. He may be worried about something that isn’t going to happen at all.

Provide a developmentally appropriate explanation of why the surgery is being performed; encourage the child to ask questions. Pictures or illustrations can be very helpful in assisting the child to understand the explanations.

Reassure the child that he won’t wake up during the surgery but that the doctor knows how and when to wake him up afterward.

Show the child an induction mask (if it will be used) and allow him to “practice” by placing it on his face (or yours).

Prepare the child for equipment (monitors, drains, and intravenous [I.V.] injections, for example) he’ll wake up with.

Tell the child about the sights and sounds of the operating room.

Tell the child that his doctor and nurse will be in the operating room with him. Reassure him that they’ll talk to him and tell him what’s happening.

If possible, show the child where he’ll be waking up in the recovery room and where his parents will be waiting for him.

Tell the child it’s perfectly fine to be afraid and to cry.

After the surgery, encourage the child to talk about the experience; he may also express his feelings through art or play.

Stress to the child and parents the importance of antibiotic therapy before dental work and other invasive procedures to prevent infective endocarditis. Children who undergo valve replacement will always need this type of prophylactic antibiotic therapy.

Teach the child and parents the importance of good oral hygiene to reduce the risk of oral infection, which may lead to bacteremia.

Inform the child and parents that clicking of the mechanical heart valve may be heard outside of the chest. Reinforce that this sound is normal.

Cardiac catheterization

Cardiac catheterization is performed with a radiopaque catheter that’s passed through the femoral artery directly into the heart and lungs. It may also be performed in conjunction with angiography, in which a radiopaque contrast medium is injected through the catheter into the circulation, allowing visualization of blood circulation through the heart chambers.

Measure for measure

Cardiac catheterization is used to evaluate ventricular function and measure heart chamber pressures and oxygen saturation in the blood. It also serves as a method for obtaining cardiac muscle biopsy specimens and for performing electrophysiologic studies.

Complications

Complications of cardiac catheterization include acute hemorrhage, transient arrhythmias, temporary diminished circulation to the catheterized extremity because of clot or hematoma formation, allergic reaction to the contrast medium, nausea and vomiting, and the possibility of infection.

Nursing considerations

Nursing interventions for cardiac catheterization begin when the procedure is scheduled and continue throughout the recovery period.

Before the procedure

Before catheterization, nursing interventions focus on preparing the child for the procedure, both physically and emotionally.

Describe to the child and parents the procedure room as well as the equipment that will be used during the procedure. Show the child where on his body the catheter will be inserted, using doll play to prepare him, as necessary.

Tell the child that the lights in the room will be dimmed after the catheter is placed. Reassure him that you’ll be right there with him and will talk to him throughout the procedure.

Tell the child that he may feel warm after the contrast medium is injected.

Weigh the child and take his vital signs.

Assess the child’s color, temperature of his extremities, and pedal pulses. Mark the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses with indelible ink before the procedure, allowing for easy assessment after the procedure.

|

After the procedure

After catheterization, nursing care focuses on preventing complications, monitoring the catheterized extremity, and ensuring adequate fluid intake.

Keep the affected extremity immobile to prevent hemorrhage, usually for 4 to 6 hours after the procedure.

Keep the catheter site clean and dry; monitor for bleeding and hematoma formation.

Compare postcatheterization assessment data to precatheterization baseline data, paying special attention to pulses and neurovascular status in the catheterized extremity.

Ensure adequate fluid intake (I.V. and oral) to compensate for blood loss during the procedure and the diuretic action of some contrast media used. Doing so will also aid in flushing the contrast medium from the circulation.

Because cardiac catheterization is commonly done on an outpatient basis, provide thorough postprocedure teaching for the parents. (See Instructions after cardiac catheterization.)

Cardiac surgery

Treatment of almost all congenital heart defects is achieved through cardiac surgery. The specific procedure performed will depend on the defect. Even so, certain methods are used no matter which procedure is performed.

Heart-lung vacation

Cardiopulmonary bypass machines are typically used to oxygenate body tissues because surgery may necessitate stopping the heart. During the procedure, the patient is placed in a hypothermic state to minimize blood loss (which enhances patient recovery) and to reduce the body’s need for oxygen. An incision into the chest (thoracotomy) is commonly performed, and chest tubes are placed.

It’s all relative

It’s all relativeInstructions after cardiac catheterization

Cardiac catheterizations are commonly performed on an outpatient basis. Provide parents with these clear instructions about caring for their child at home:

Remove the pressure dressing the day after the procedure.

Keep the site covered with an adhesive bandage for several days after the procedure.

Keep the insertion site clean and dry; give only sponge baths until the site is healed.

Observe the site for redness, swelling, drainage, and bleeding.

Monitor the child’s temperature, and report fever promptly.

Have the child avoid strenuous exercise.

Provide a regular diet for the child.

Administer acetaminophen or ibuprofen as needed for discomfort or pain.

Keep follow-up appointments.

Complications

Complications of cardiac surgery may include arrhythmias, acidbase and electrolyte imbalances, hypoxia, and trauma to the conduction pathways of the heart.

Nursing considerations

Prepare the child (and his parents) for what he’ll see, hear, and feel after surgery. When a child and his parents know ahead of time that certain events are “normal,” those events will be less stressful and frightening when they occur.

Monitor the patient’s heart rate closely. (It will normally increase after surgery.) Changes in regularity and rhythm should be reported to the doctor immediately.

Auscultate the lungs every hour, assessing for diminished or absent breath sounds, which may require further medical evaluation and intervention.

Keep the heat

Keep the child warm to prevent heat loss. (Infants may be placed under radiant heat warmers.)

Monitor body temperature closely. It may rise to about 100° F (37.8° C) in the first 48 hours after surgery due to the inflammatory process initiated by tissue trauma. (Further temperature elevation may indicate an infection, requiring immediate action to determine the cause.)

Chest tube removal

Follow these guidelines to prepare the child for chest tube removal and to reduce complications:

Tell the child he’ll experience momentary sharp pain as the chest tube is removed.

Administer anesthetics or analgesics as ordered.

Instruct the child to take a deep breath. (The tube should be removed at the end of inspiration.)

Cover the wound with sterile petroleum gauze, topped with a clear, occlusive film dressing, such as Tegaderm, making sure all sides are securely attached to the skin for an airtight seal.

Monitor the site for drainage, bleeding, and infection. Change the dressing according to your facility’s policy.

Maintain mechanical ventilation of the child in the immediate postoperative period. Extubation may occur in the operating room or in the early postoperative period.

After extubation, an oxygen mask, hood, or tent or nasal cannula is used to deliver humidified oxygen. If the patient is in an oxygen tent, change his linens and clothes frequently to keep them dry, preventing excessive chilling that would increase metabolic needs and, consequently, increase cardiac and oxygen demand.

Turn and breathe

Implement turning and deep breathing hourly, using adjunct analgesics and splinting of the incision to minimize discomfort and pain. Firm stuffed animals can be used effectively for incisional support during deep-breathing and spirometry exercises.

Prepare the child for chest tube removal (typically between the first and third postoperative day), which can be a painful and frightening procedure for a child. Topical anesthetics or analgesics are commonly administered before removal. (See Chest tube removal.)

Rx: TLC

Provide emotional support and comfort because surgery can be frightening as well as painful to the child. (Encourage parental involvement in the child’s care to foster feelings of comfort and security.)

Provide detailed discharge teaching. (See Teaching about cardiac surgery.)

Cardiac transplantation

For infants and children with worsening heart failure and limited life expectancy, heart transplantation has become an option. Indications for transplantation in children include cardiomyopathy and end-stage congenital heart disease.

One of two

There are two surgical options for cardiac transplantation:

orthotopic procedure, in which the diseased heart is removed in its entirety and a new, healthy heart from a donor (who has been declared brain dead) is implanted

heterotopic procedure (rarely performed in children), in which the patient’s own heart is kept in place and a “piggyback” heart is implanted to serve as an additional pumping organ to assist the diseased heart.

Who knows UNOS?

The process begins by placing the child on the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) list to match a donor with the recipient. Due to limited donor supply, 30% of infants on the UNOS list die before a new heart can be found for them. Approximately 300 to 400 transplants are performed per year on pediatric patients.

Crucial 6 months

Complications are most common during the first 6 months to 1 year after transplantation. During this period, the family must adjust to a totally new lifestyle that will require lifelong management. The leading cause of demise after heart transplantation is organ rejection. Because lifelong immunosuppressive therapy is required, infection is always a risk.

Nursing considerations

The child and his parents must be prepared thoroughly for this major procedure. Preparation should include a brief visit to the coronary intensive care unit (CICU) and, if possible, the child should be introduced to the nurses who will be providing his care. Parents should be made aware of the visiting policies in the CICU and should be assisted in making arrangements (in the hospital and at home) to spend as much time with their child as possible.

It’s all relative

It’s all relativeTeaching about cardiac surgery

Be sure to include these points in your teaching plan for the parents of a child who has undergone cardiac surgery:

dietary restrictions, if any

fluid requirements and restrictions

activity and exercise restrictions

operative site care and inspection

medication regimen

follow-up tests and doctor visits

home care needs

importance of encouraging the child to talk and express his feelings about the surgery and hospitalization.

The hard part is over

Postoperative care involves:

|

monitoring the patient closely for signs of rejection, infection, and adverse reactions from immunosuppressive therapy

restricting fluids as ordered to prevent hypervolemia and heart strain

providing adequate rest periods with gradual activity increases to further decrease the workload of the heart

encouraging compliance with the complex drug regimen required, especially in adolescents

providing emotional support to the child and family and offering resources for additional support

helping the parents (and the child, if age appropriate) come to terms with the reality that someone had to die for a heart to become available. (This concept is too confusing and upsetting for most young children; parents should be encouraged to provide age-appropriate explanations when the child begins to ask where his new heart came from.)

Congenital heart defects that increase pulmonary blood flow

Congenital heart defects that increase pulmonary blood flow include atrial septal defect (ASD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and ventricular septal defect (VSD).

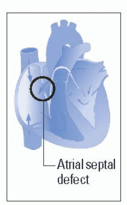

Atrial septal defect

In a child with ASD, an opening between the left and right atria allows blood to flow from the left side of the heart to the right side, resulting in ineffective pumping of the heart, thus increasing the risk of heart failure. (See Looking at ASD.)

ASDs come in threes

The three types of ASDs are:

ostium secundum defect, the most common type, which occurs in the region of the fossa ovalis at the center of the atrial septum and, occasionally, extends inferiorly, close to the vena cava

ostium secundum defect, the most common type, which occurs in the region of the fossa ovalis at the center of the atrial septum and, occasionally, extends inferiorly, close to the vena cava sinus venosus defect, which occurs in the superior-posterior portion of the atrial septum, sometimes extends into the vena cava,

sinus venosus defect, which occurs in the superior-posterior portion of the atrial septum, sometimes extends into the vena cava, and is almost always associated with abnormal drainage of pulmonary veins into the right atrium

Benign when small

ASD accounts for about 10% of congenital heart defects and is almost twice as common in females as in males, with a strong familial tendency. Although an ASD is usually a benign defect during infancy and childhood, delayed development of symptoms and complications makes it one of the most common congenital heart defects diagnosed in adults.

The prognosis is excellent for asymptomatic patients and for those with uncomplicated surgical repair. The prognosis is poor, however, in patients with cyanosis caused by large, untreated defects.

What causes it

The cause of ASD is unknown. Ostium primum defects commonly occur in patients with Down syndrome.

How it happens

In ASD, blood shunts from the left atrium to the right atrium because the left atrial pressure is normally slightly higher than the right atrial pressure. The difference in pressure forces large amounts of blood through the defect. This shunt results in right heart volume overload, affecting the right atrium, right ventricle, and pulmonary arteries.

Enlarge and dilate

Eventually, the right atrium enlarges, and the right ventricle dilates to accommodate the increased blood volume. If pulmonary artery hypertension develops, increased pulmonary vascular resistance and right ventricular hypertrophy follow.

Looking at ASD

An ASD is an opening between the left and right atria that allows blood to flow from the left side of the heart to the right side, as shown here.

|

What to look for

Signs and symptoms of ASD include:

fatigue after exertion

early to midsystolic murmur at the second or third left intercostal space

low-pitched diastolic murmur at the lower left sternal border (more pronounced on inspiration)

fixed, widely split S2 due to delayed closure of the pulmonic valve

systolic click or late systolic murmur at the apex

clubbing and cyanosis if a right-to-left shunt develops. (See Cyanosis and crying.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access