Chapter 5 Cardiac Health Breakdown

When you have completed this chapter you will be able to

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of disability in Australia, New Zealand and other developed countries. CVD and its manifestation in conditions, such as acute myocardial infarction, stroke and heart failure, are responsible for significant disease burden globally1–3. This chapter focuses on cardiac health breakdown, but it is important to consider the impact of other systems on the aetiology, presentation and progression of heart disease. In particular, you should consider the potential for respiratory dysfunction (Chapter 6), renal dysfunction (Chapter 7), and haematological disturbances (Chapter 12). Although cardiovascular dysfunction can manifest in numerous conditions, this chapter will focus on the discussion of the diagnosis and management of the commonly encountered clinical problems of acute coronary syndromes, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. As you work through this chapter, it is important to remember that cardiac health breakdown often occurs in the elderly and is often only one of their co-morbid chronic diseases. This increases the complexity of management, and, particularly, the potential for drug interactions. For example, a patient may be prescribed a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication for osteoarthritis, but this may have a deleterious effect on the renal function of a patient with chronic heart failure.

CVD, manifested as acute coronary syndrome (ACS) – unstable angina pectoris, or acute myocardial infarction – and heart failure (HF) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in industrialised societies. Australians aged over 60 years account for 70% of acute myocardial infarctions (AMIs), 61% of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) and 73% of coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG)4. By 2020 it is estimated that in developed countries, up to 80% of disease burden with be a result of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease3. Therefore, when assessing and managing a patient, it is important not to only consider other actual or potential co-morbid conditions and the potential for drug interactions, but also the importance of promotion of self-management in the treatment plan.

Although conditions manifesting as cardiac health breakdown are chronic in nature, initial manifestations often present as acute deteriorations such as acute myocardial infarction or acute pulmonary oedema. It is disastrous that the initial presentation for many individuals may be a sudden cardiac death or a catastrophic stroke. Unfortunately, many people ignore the signs of a potential heart attack5,6. This delay in seeking treatment and the concept that cardiac health breakdown is largely preventable are the motivation behind widespread public health campaigns to urge individuals to look at modifiable risk factors such as high blood pressure, obesity and physical inactivity7–10.

Due to the high prevalence of heart disease, cardiology is the focus of substantive research and is a dynamic and evolving science. Consequently, clinical practice changes rapidly and it is important for the clinician to keep abreast of changes and recent developments in detection, management and prevention. A good way to do this is to access the web sites of key professional bodies that are responsible for the development of best practice guidelines. These include the Heart Foundation of Australia; National Heart Foundation of New Zealand, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand; Australian College of Critical Care Nurses, American Heart Association; American College of Cardiology; Heart Failure Society of America and European College of Cardiology. A list of these web sites is given at the end of this chapter.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE HEART

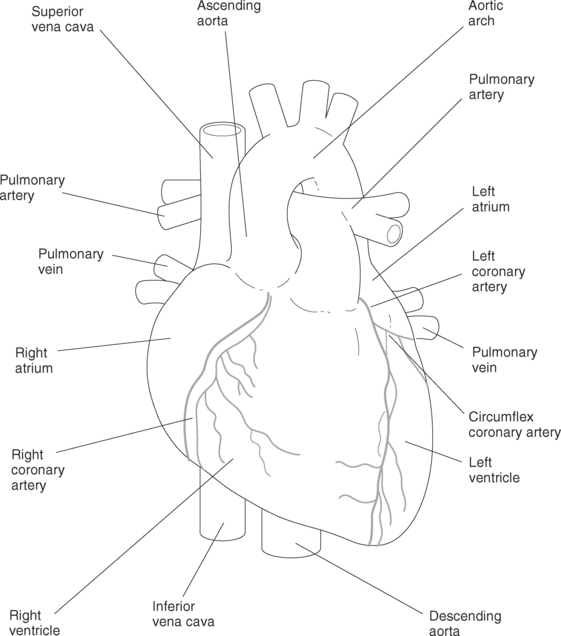

The heart is a four-chambered muscular organ responsible for circulating blood around the body. These chambers are known as the right atrium; the right ventricle; the left atrium and the left ventricle. Blood enters the heart via the atria. There are two large veins, which enter the heart on the right hand side and bring deoxygenated blood into the right atrium. The superior vena cava brings in deoxygenated blood from the upper extremities of the body and the head while the inferior vena cava brings in blood from the body and the lower extremities. This deoxygenated blood is fed into the right ventricle and taken to the lungs where gas exchange occurs (see Chapter 6), before returning to the left atrium through the right and left pulmonary veins. The oxygen-rich blood enters the left side of the heart and is pumped out into the systemic circulation by the larger left ventricle. Blood leaves the heart via the aorta, the largest artery in the body, into the upper body via the arteries branching off the aortic arch and into the thorax, trunk and lower body via the descending aorta. These anatomical features are shown in Figure 5.1.

CORONARY ARTERIES

The right and left coronary arteries branch off the aorta (see Figure 5.1). If the coronary arteries become narrowed by deposits of cholesterol in the lining of the arteries (atherosclerosis) then the flow of blood to the myocardium (heart muscle) may be restricted. This is a common cause of ischaemia and subsequent myocardial infarction.

CARDIAC OUTPUT

The term cardiac output (CO) is defined as the amount of blood, in litres, that is ejected by the heart each minute. The calculation of CO is based on the product of heart rate and stroke volume. Stroke volume is defined as the amount of blood ejected from the heart with each heartbeat. It is determined by factors including preload, afterload and contractility. Preload is the amount of volume or pressure in the ventricle at end-diastole while afterload is the resistance the heart has to overcome in order to eject the blood. Simplistically, contractility is the ability of the heart to stretch and contract11.

PREVENTION, DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF CARDIAC HEALTH BREAKDOWN

SELF-CARE AND SELF-MANAGEMENT IN CARDIAC HEALTH BREAKDOWN

Adjustment to a diagnosis of cardiac health breakdown has implications for self-care12. In order to promote self-care in patients, information, systems, processes and support are required to maximise risk-factor modification and adherence to lifestyle modifications13. Self-care strategies need to be customised to the individual and optimally incorporates family members and significant others in care planning. The growing burden of chronic disease accentuates the importance of self-management principles in chronic-disease management. Given the cultural diversity of contemporary society, it is important that treatment plans are appropriate to culturally and linguistically diverse groups14,15.

KEY ELEMENTS OF DIAGNOSIS OF CARDIAC HEALTH BREAKDOWN

Key elements of a complete cardiac diagnosis include consideration of anatomic and physiological disturbances, functional status and disease aetiology16. Key aspects in taking a focused history include17

In 2003, the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NHF) released a position statement, informed by a systematic review, that clearly identified these issues as significant risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD)20. This review concluded that there is evidence of an independent causal association between depression, social isolation and lack of quality social support and the aetiology and outcome of CHD.

DETERMINING A DIAGNOSIS OF CARDIAC HEALTH BREAKDOWN

Determining a cardiac diagnosis is dependent on a comprehensive history and physical examination of the patient. Despite the myriad technological investigations available to the health professionals (see Table 5.1), clinical assessment remains the basis for the diagnosis of many conditions and the development of a plan for diagnostic testing and cardiovascular therapeutics. Clinical examination and history are facilitated by diagnostic tests including: 1) the electrocardiogram; 2) chest X-ray; 3) echocardiogram; 4) radionuclide and imaging techniques; 5) coronary angiography; and 6) laboratory tests. The chest X-ray can help differentiate patients with a normal-sized heart from patients with an enlarged cardiac silhouette, suggesting acute exacerbation of some underlying form of chronic heart failure, or identify pulmonary oedema (suggesting heart failure secondary to acute myocardial infarction, or valvular insufficiency, or pulmonary congestion)16. Pathophysiological presentations of cardiac health breakdown are numerous and diverse and texts discussing these can be found in the list of recommended readings.

TABLE 5.1 COMMON DIAGNOSTIC TESTS IN SUSPECTED CARDIAC HEALTH BREAKDOWN

| Diagnostic Test | Description |

|---|---|

| Using ultrasound technology these tests show the structure and function of the heart, in particular, the heart valves and muscle function | |

| These tests monitor the electrical function of the heart and diagnose cardiac arrhythmias | |

| These diagnostic tests assess circulation in the coronary system and the pumping function of the heart |

GUIDING PRINCIPLES IN THE MANAGEMENT PLAN OF CARDIAC HEALTH BREAKDOWN

Once a diagnosis of heart disease is made, the therapeutic regimen is developed. Key factors to consider in the development of the treatment plan are the use of evidence-based strategies with consideration of the following factors:

MYOCARDIAL ISCHAEMIA

Myocardial ischaemia can occur as a result of:

Symptoms of myocardial ischaemia are often described as angina and manifest frequently as chest discomfort. In addition, reduction of cardiac output can lead to symptoms such as weakness and fatigue. Chest discomfort, however, may result from a variety of causes other than myocardial ischemia. Conversely, many individuals with myocardial ischaemia may not experience any chest pain or discomfort21,22.

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

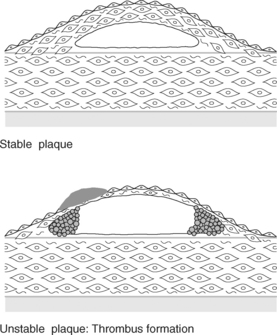

Coronary heart disease is the most common form of heart disease in adults and may manifest as angina, heart failure, arrhythmias, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and sudden cardiac death21,23. Coronary heart disease continues to be the leading cause of death among adults in the Australia and New Zealand, and remains so despite improvements in prevention and treatment of disease24,25. The treatment of AMI has evolved dramatically over the past 20 years from bed rest, and management of associated complications, to aggressive reperfusion strategies (primary angioplasty and thrombolytic therapy) and other measures to minimise myocardial damage26. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) refers to a set of clinical symptoms that result from rupture of vulnerable plaques in the coronary arteries21. Conceptually, ACS is viewed as a continuum representing the relationship between the vulnerable plaque and coronary artery22. The vulnerability of plaque and subsequent clot formation and impairment of coronary artery blood flow, represented schematically in Figure 5.2, dictates the therapeutic management strategies of ACS.

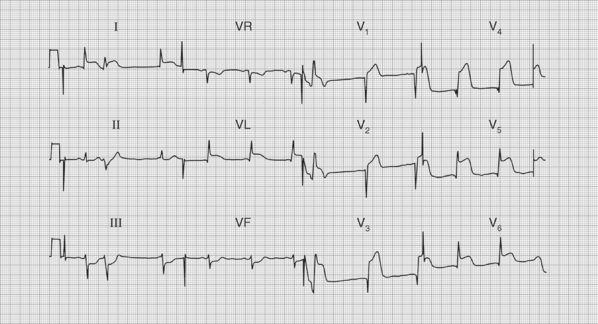

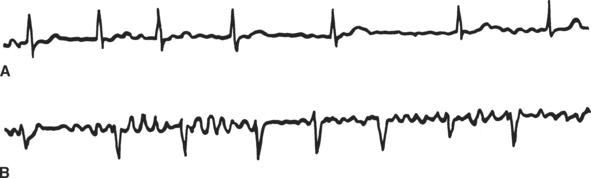

Occasionally, concomitant conditions, such as atrial fibrillation (see Figure 5.3), complicate clinical management. From clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives, this continuum ranges from unstable angina pectoris (UAP), where ischaemic symptoms can occur at rest and be protracted, non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI), where symptoms are associated with electrocardiographic changes and elevation of cardiac markers, through to ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI), as illustrated in Figure 5.4, and sudden cardiac death. The result of ruptured atherosclerotic plaque and decrease of coronary blood flow may lead to development of heart failure or sudden cardiac death. Unfortunately, sudden cardiac death can be the initial, disastrous manifestation of ACS21. A key diagnostic tool in ACS is the electrocardiogram (ECG). An ECG measures and records the electrical activity (depolarisation and repolarisation) of the heart muscle. The configuration of the ECG reflects the patterns of contraction and relaxation throughout the heart. Abnormalities of the ST segment are reflecting changes in the repolarisation pattern of the ventricles. This can be due to myocardial ischaemia or infarction, pericarditis or ventricular hypertrophy. When ST segments are elevated this is highly suggestive of an acute myocardial infarction and is usually termed a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). ST segment elevation in association with symptoms of ischaemia, such as chest pain and shortness of breath, requires urgent treatment to unblock affected arteries. A depressed or horizontal ST wave suggests impaired blood flow to the myocardium. If this finding occurs within the context of ischaemic symptoms and elevated cardiac markers this may be termed non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI).

FIGURE 5.3 Rhythm strip identifying atrial fibrillation

Source: Hampton, J. 2002; The ECG Made Easy (5th ed.), Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 79.

The precipitator of an ACS event is thought to be rupture or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque in a coronary artery due to inflammation followed by thrombosis. Several factors may precipitate the rupture of vulnerable plaque. This rupture leads to the activation, adhesion, and aggregation of platelets and the activation of the clotting cascade, resulting in the formation of an occlusive thrombus. Local thrombosis, occurring after plaque disruption, results from complex interactions between clotting factors, the lipid core of the plaque, exposed smooth-muscle cells, macrophages, and collagen. In response to the disruption of the endothelial wall, platelets aggregate and release their granular contents, which further propagate platelet aggregation and promote vasoconstriction and thrombus formation. If this process leads to complete occlusion of the artery, then acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation occurs. Alternatively, if the process leads to severe stenosis but the artery nonetheless remains patent, then unstable angina occurs. Coronary vasospasm may also contribute to vascular instability by altering pre-existing coronary plaques, which causes intimal disruption and penetration of macrophages or aggregation of platelets. Rapid proliferation and migration of smooth-muscle cells in response to endothelial injury may lead to narrowing of the coronary arteries and ischaemic symptoms22.

UNSTABLE ANGINA PECTORIS

The diagnosis of UAP may be based on any of the following clinical presentations:

NON-ST-SEGMENT ELEVATION MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION (NSTEMI)

NSTEMI differs from UAP in terms of diagnosis, therapy and prognosis on the basis of ECG changes. These two differential diagnoses are often indistinguishable at presentation based upon clinical history. NSTEMI involves ischaemia severe enough to result in myocardial damage, although cardiac markers (cardiac markers such as troponins and enzymes, e.g., creatinine kinase MB) may not be elevated until several hours after onset of ischaemic symptoms. Therapeutically, interventions are aimed at arresting the progression of the ACS presentation from NSTEMI to STEMI where there is greater risk of loss of myocardium and subsequent complications. The complications of STEMI are listed in Table 5.2.

TABLE 5.2 COMPLICATIONS OF STEMI16,80–82

| Recurrent ischaemia |

| Pericarditis |

| Reinfarction |

| Acute heart failure |

| Chronic heart failure |

| Thromboembolism |

| Ventricular septal rupture |

| Reinfarction |

| Infarct extension |

| Left ventricular aneurysm |

| Arrhythmias |

| Mitral valve dysfunction |

INITIAL EVALUATION IN A PATIENT SUSPECTED OF HAVING AN ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME

TABLE 5.3 PREVENTABLE RISK FACTORS FOR CARDIAC HEALTH BREAKDOWN

| Tobacco smoking |

| High blood pressure |

| High blood cholesterol |

| Obesity |

| Insufficient physical activity |

| High alcohol intake |

| Type 2 diabetes |

| Stress and other psychosocial factors |

This information will assist the clinician in developing a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. For example, it is futile to perform a coronary angiogram with the associated risks on a patient who has previously declined coronary artery bypass surgery unless they are prepared to follow through with invasive therapeutic options. Similarly it is important that patients appreciate the risks and benefits associated with thrombolytic therapy and primary angioplasty. The factors above also help the clinician to assess prognosis and risk. This will guide diagnostic, therapeutic and management decisions. For example, it will dictate whether the patient should undergo an immediate percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and where the patient is best managed. That is, whether the patient is best managed in a coronary care unit (CCU) or a step-down or sub acute unit. As the risk of complications increases with treatment delays, clinicians must make certain clinical decisions, concerning the appropriate level of care, immediately after obtaining the ECG27,28.

MAKING A DIAGNOSIS OF ACS AND DEVELOPING A MANAGEMENT PLAN

The presentation of a patient with ACS can be varied, ranging from people with diabetes who do not experience typical ‘chest pain’ associated with heart attack (because of impaired autonomic function), through to the crushing central chest pain we view as ‘typical chest pain’. All patients who present with chest tightness, pressure or pain (which may radiate to the jaw, the neck, or either or both arms) must be assumed to have possible ACS. In addition, people who have symptoms of ‘indigestion’, shortness of breath, extreme fatigue, or dizziness should also be systematically assessed for the presence of heart disease. Dyspnoea, diaphoresis, nausea, and/or vomiting should also increase the index of suspicion of ACS. Older patients may present with syncope, or dyspnoea without experiencing chest pain. Women are more likely than men to present with symptoms considered to be ‘atypical’29. This makes the diagnosis of ACS complex, particularly in busy emergency departments. In the USA, failure to diagnose ACS is the most common cause of litigation for emergency physicians. However, following the steps listed below decreases the likelihood of ‘missing’ a diagnosis of ACS in the clinical setting.

The important inverse relationship between delay from onset of ischaemic symptoms to reperfusion strategies and prognosis underscores the importance of early presentation and the important role of effective triage30. The ECG remains an accessible and effective screening tool in conjunction with an astute physical assessment. Localised pain in the absence of other symptoms; a low-risk profile and a normal ECG may assist in ruling out ACS. Many diagnostic algorithms exist to assist clinicians in making these decisions based on clinical symptoms.

Key elements of making a diagnosis of ACS are the

CARDIAC MARKERS AND ENZYMES

The troponin complex regulates the contraction of striated muscle and consists of three types:

Under usual conditions, cardiac troponin T and cardiac troponin I are not detectable in the blood of healthy persons. Release of these substances occurs when myocytes are damaged by conditions such as trauma, inflammation, and impairment of blood flow due to ACS. Following necrosis of myocardial tissue creatinine kinase (CK) is released. Skeletal muscle contains less than 3% CKMB, whereas the muscle of the heart contains up to 20% of CKMB, therefore CKMB has increased specificity for myocardial damage. Troponin I and T are commonly used as they show earlier elevated levels in the presence of myocardial injury (median 3.8 hours for troponin T versus 4.8 hours for CKMB31,33).

RISK ASSESSMENT DETERMINES TREATMENT IN CARDIAC HEALTH BREAKDOWN

In ACS, the level of risk determines the management strategy and level of intervention. Following are listed the characteristics of high, intermediate and low-risk factors34:

LOW-RISK FEATURES

It is a chilling fact that more than 50% of all heart attack deaths occur before the patient reaches hospital6. This underscores the importance of early symptom recognition and public access to automated defibrillators5,35–37. The great majority of AMI patients currently do not receive the benefit of thrombolytic and other treatments within the first hour of symptom onset6,30. Both acute mortality and subsequent prognosis are related to the extent to which the myocardium is damaged by the infarction. Strategies focusing on early reperfusion can prevent myocardial necrosis, and clinical trials with thrombolytic agents demonstrating a significant reduction in AMI mortality have dramatically improved outcomes for AMI patients. The case study below gives a scenario of a usual or common presentation and management of a patient with a diagnosis of ACS.

Initial actions for management of an ACS event22 are as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree