Coronary Artery Disease

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death in the United States. CAD is characterized by the accumulation of plaque within the layers of the coronary arteries. The plaques progressively enlarge, thicken, and calcify, causing a critical narrowing (>70% occlusion) of the coronary artery lumen, resulting in a decrease in coronary blood flow and an inadequate supply of oxygen to the heart muscle.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is an umbrella term that is used to describe many of the complications associated with CAD. These include unstable angina, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Pathophysiology and Etiology

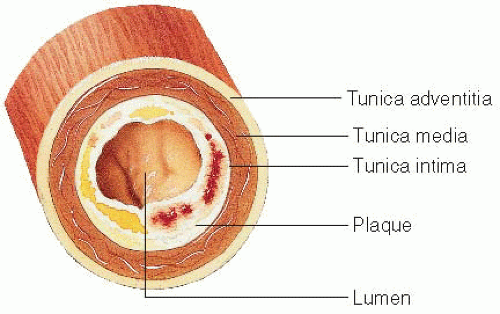

The most widely accepted cause of CAD is atherosclerosis (see

Figure 13-1), which is the gradual accumulation of plaque within an artery forming an atheroma. Plaque consists of lipid-filled macrophages (foam cells), fibrin, cellular waste products, and plasma proteins, covered by a fibrous outer layer (smooth muscle cells and dense connective tissue).

When the endothelium is injured by being exposed to low-density lipoproteins, by-products of cigarette smoke, hypertension, hyperglycemia, infection, and increased homocysteine, hyperfigrinogenemia, and lipoprotein(a), an inflammatory response occurs, making the endothelium sticky and thereby attracting adhesion molecules.

Over time, the plaque thickens, extends, and calcifies, causing narrowing of the lumen.

Eventual hemorrhage and ulceration of the plaque may cause significant coronary obstruction.

Angina pectoris, caused by inadequate blood flow to the myocardium, is the most common manifestation of CAD.

Angina is usually precipitated by physical exertion or emotional stress, which puts an increased demand on the heart to circulate more blood and oxygen.

The ability of the coronary artery to deliver blood to the myocardium is impaired because of obstruction by a significant coronary lesion (>70% narrowing of the vessel).

Angina can also occur in other cardiac problems, such as arterial spasm, aortic stenosis, cardiomyopathy, or uncontrolled hypertension.

Noncardiac causes include anemia, fever, thyrotoxicosis, and anxiety/panic attacks.

ACS is caused by a decrease in the oxygen available to the myocardium due to:

Unstable or ruptured atherosclerotic plaque.

Coronary vasospasm.

Atherosclerotic obstruction without clot or vasospasm.

Inflammation or infection.

Unstable angina due to a noncardiac cause.

Risk factors for the development of CAD include:

Nonmodifiable: age (risk increases with age), male sex (women typically suffer from heart disease 10 years later

than men due to the postmenopausal decrease in cardiacprotective estrogen), race (nonwhite populations have increased risk), and family history.

Modifiable: elevated lipid levels, hypertension, obesity, tobacco use, metabolic syndrome (obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus), sedentary lifestyle, and stress.

Recent studies have shown that there are new risk factors associated with the development of CAD. These include increased levels of homocysteine, fibrin, lipoprotein(a), and infection or inflammation (measured by C-reactive protein [CRP]).

The American Heart Association (AHA) also lists left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) as a risk factor.

The Framingham Scoring Method is used to determine the 10-year risk of development of coronary heart disease (CHD) in men and women based on age, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level, systolic blood pressure (BP), presence of hypertension, and cigarette smoking. More information can be found at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/index.htm.

Clinical Manifestations

Chronic Stable Angina Pectoris

Chest pain or discomfort that is provoked by exertion or emotional stress and relieved by rest and nitroglycerin.

Character—substernal chest pain, pressure, heaviness, or discomfort. Other sensations include a squeezing, aching, burning, choking, strangling, and/or cramping pain.

Pain may be mild or severe and typically presents with a gradual buildup of discomfort and subsequent gradual fading.

May produce numbness or weakness in arms, wrists, or hands.

Associated symptoms include diaphoresis, nausea, indigestion, dyspnea, tachycardia, and increase in blood pressure.

Women may experience atypical symptoms of chest pain, such as jaw pain, shortness of breath, or indigestion. Patients with diabetes or history of heart transplant may not experience chest pain.

Location—behind middle or upper third of sternum; the patient will generally make a fist over the site of the pain (positive Levine’s sign, indicating diffuse deep visceral pain) rather than point to it with his or her finger.

Radiation—usually radiates to neck, jaw, shoulders, arms, hands, and posterior intrascapular area. Pain occurs more commonly on the left side than the right.

Duration—usually lasts 2 to 15 minutes after stopping activity; nitroglycerin relieves pain within 1 minute.

Other precipitating factors—exposure to weather extremes, eating a heavy meal, and sexual intercourse all increase the workload of the heart, thus increasing oxygen demand.

Unstable (Preinfarction) Angina Pectoris

Chest pain occurring at rest; no increase in oxygen demand is placed on the heart, but an acute lack of blood flow to the heart occurs because of coronary artery spasm or the presence of an enlarged plaque or hemorrhage/ulceration of a complicated lesion. Critical narrowing of the vessel lumen occurs abruptly in either instance.

A change in frequency, duration, and intensity of stable angina symptoms is indicative of progression to unstable angina.

Unstable angina pain lasts longer than 10 minutes, is unrelieved by rest or sublingual nitroglycerin, and mimics signs and symptoms of impending MI.

Silent Ischemia

The absence of chest pain with documented evidence of an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand (ST depression of 1 mm or more) as determined by electrocardiography (ECG), exercise stress test, or ambulatory (Holter) ECG monitoring.

Silent ischemia most commonly occurs during the first few hours after awakening (circadian event) due to an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity, causing an increase in heart rate, blood pressure, coronary vessel tone, and blood viscosity.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Characteristic chest pain and clinical history.

Nitroglycerin test—relief of pain with nitroglycerin.

Blood tests.

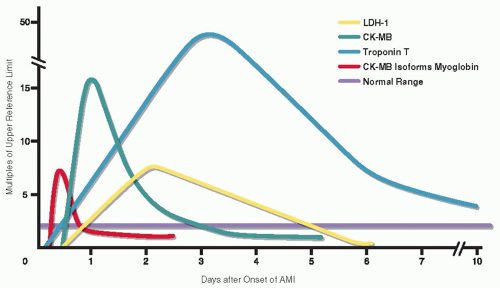

Cardiac markers, creatine kinase (CK) and its isoenzyme CK-MB, and troponin-I to determine the presence and severity if acute cardiac insult is suspected.

HbA1C and fasting lipid panel to rule out modifiable risk factors for CAD.

Coagulation studies, CRP, homocysteine, and lipoprotein(a) (increased levels are associated with a twofold risk in developing CAD).

Hemoglobin to rule out anemia, which may reduce myocardial oxygen supply.

12-lead ECG—may show LVH, ST-T wave changes, arrhythmias, and Q waves.

ECG stress testing—progressive increases of speed and elevation while walking on a treadmill increase the workload of the heart. ST-T wave changes occur if myocardial ischemia is induced.

Radionuclide imaging—a radioisotope, thallium 201, injected during exercise is imaged by camera. Low uptake of the isotope by heart muscle indicates regions of ischemia induced by exercise. Images taken during rest show a reversal of ischemia in those regions affected.

Radionuclide ventriculography (gated blood pool scanning)—red blood cells tagged with a radioisotope are imaged by camera during exercise and at rest. Wall motion abnormalities of the heart can be detected and ejection fraction estimated.

Cardiac catheterization—coronary angiography performed during the procedure determines the presence, location, and extent of coronary lesions.

Positron-emission tomography (PET)—cardiac perfusion imaging with high resolution to detect very small perfusion differences caused by stenotic arteries. Not available in all settings.

Electron-beam computed tomography (CT)—detects coronary calcium, which is found in most, but not all, atherosclerotic plaque. It is not routinely used due to its low specificity for identifying significant CAD.

Management

Drug Therapy

Antianginal medications (nitrates, beta-adrenergic blockers, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors) are used to maintain a balance between oxygen supply and demand. Coronary vessel relaxation promotes blood flow to the heart, thereby increasing oxygen supply. Reduction of the workload of the heart decreases oxygen demand and consumption. The goal of drug therapy is to maintain a balance between oxygen supply and demand.

Nitrates—caused by generalized vasodilation throughout the body. Nitrates can be administered via oral, sublingual, transdermal, intravenous (IV), or intracoronary (IC) route and may provide short- or long-acting effects.

Short-acting nitrates (sublingual) provide immediate relief of acute anginal attacks or prophylaxis if taken before activity.

Long-acting nitrates prevent anginal episodes and/or reduce severity and frequency of attacks.

Beta-adrenergic blockers—inhibit sympathetic stimulation of receptors that are located in the conduction system of the heart and in heart muscle.

Some beta-adrenergic blockers inhibit sympathetic stimulation of receptors in the lungs as well as the heart (“nonselective” beta-adrenergic blockers); vasoconstriction of the large airways in the lung occurs; generally contraindicated for patients with chronic obstructive lung disease or asthma.

“Cardioselective” beta-adrenergic blockers (in recommended dose ranges) affect only the heart and can be used safely in patients with lung disease.

Calcium channel blockers—inhibit movement of calcium within the heart muscle and coronary vessels; promote vasodilation and prevent/control coronary artery spasm.

ACE inhibitors—have therapeutic effects by remodeling the vascular endothelium and have been shown to reduce the risk of worsening angina.

Antilipid agents—reduce total cholesterol and triglyceride levels and have been shown to assist in the stabilization of plaque.

Antiplatelet agents—decrease platelet aggregation to inhibit thrombus formation.

Folic acid and B complex vitamins—treat increased homocysteine levels.

Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

Other Interventional Strategies

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

Transmyocardial revascularization—by means of a laser beam, small channels are formed in the myocardium to encourage new blood flow.

Secondary Prevention

Cessation of smoking.

Control of high blood pressure (below 130/85 mm Hg in those with renal insufficiency or heart failure; below 130/80 mm Hg in those with diabetes; below 140/90 mm Hg in all others).

Diet low in saturated fat (<7% of calories), cholesterol (<200 mg/day), trans-fatty acids, sodium (<2 g/day), alcohol (2 or fewer drinks/day in men, 1 or fewer in women).

Low-dose aspirin daily for those at high risk.

Physical exercise (at least 30 to 60 minutes of moderateintensity exercise most days).

Weight control (ideal body mass index 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2); waist circumference less than 40 inches for men, less than 35 inches for women.

Control of diabetes mellitus (fasting glucose < 110 mg/dL and HbA1C < 7%).

Control of blood lipids with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) goal less than 100 mg/dL (less than 70 mg/dL in high-risk patients).

Nursing Assessment

Ask patient to describe anginal attacks.

When do attacks tend to occur? After a meal? After engaging in certain activities? After physical activities in general? After visits of family/others?

Where is the pain located? Does it radiate?

Was the onset of pain sudden? Gradual?

How long did it last—Seconds? Minutes? Hours?

Was the pain steady and unwavering in quality?

Is the discomfort accompanied by other symptoms? Sweating? Light-headedness? Nausea? Palpitations? Shortness of breath?

Is there anything that makes it worse (such as moving, deep breathing, food)?

How is the pain relieved? How long does it take for pain relief?

Obtain a baseline 12-lead ECG.

Assess patient’s and family’s knowledge of disease.

Identify patient’s and family’s level of anxiety and use of appropriate coping mechanisms.

Gather information about the patient’s cardiac risk factors. Use the patient’s age, total cholesterol level, LDL and HDL levels, systolic BP, and smoking status to determine the patient’s 10-year risk for development of CHD according to the Framingham Risk Scoring Method.

Evaluate patient’s medical history for such conditions as diabetes, heart failure, previous MI, or obstructive lung disease that may influence choice of drug therapy.

Identify factors that may contribute to noncompliance with prescribed drug therapy.

Review renal and hepatic studies and complete blood count (CBC).

Discuss with patient current activity levels. (Effectiveness of anti-anginal drug therapy is evaluated by patient’s ability to attain higher activity levels.)

Discuss patient’s beliefs about modification of risk factors and willingness to change.

Nursing Diagnoses

Acute Pain related to an imbalance in oxygen supply and demand.

Decreased Cardiac Output related to reduced preload, afterload, contractility, and heart rate secondary to hemodynamic effects of drug therapy.

Anxiety related to chest pain, uncertain prognosis, and threatening environment.

Nursing Interventions

Relieving Pain

Determine intensity of patient’s angina.

Ask patient to compare the pain with other pain experienced in the past and, on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain), rate current pain.

Observe for associated signs and symptoms, including diaphoresis, shortness of breath, protective body posture, dusky facial color, and/or changes in level of consciousness (LOC).

Position patient for comfort; Fowler’s position promotes ventilation.

Administer oxygen, if appropriate.

Obtain BP, apical heart rate, and respiratory rate.

Obtain a 12-lead ECG.

Administer anti-anginal drug(s), as prescribed.

Report findings to health care providers.

Monitor for relief of pain and note duration of anginal episode.

Take vital signs every 5 to 10 minutes until angina pain subsides.

Monitor for progression of stable angina to unstable angina: increase in frequency and intensity of pain, pain occurring at rest or at low levels of exertion, pain lasting longer than 5 minutes.

Determine level of activity that precipitated anginal episode.

Identify specific activities patient may engage in that are below the level at which anginal pain occurs.

Reinforce the importance of notifying nursing staff when angina pain is experienced.

Maintaining Cardiac Output

Carefully monitor the patient’s response to drug therapy.

Take BP and heart rate in a sitting and a lying position on initiation of long-term therapy (provides baseline data to evaluate for orthostatic hypotension that may occur with drug therapy).

Recheck vital signs as indicated by onset of action of drug and at time of drug’s peak effect.

Note changes in BP of more than 10 mm Hg and changes in heart rate of more than 10 beats/minute.

Note patient complaints of headache (especially with use of nitrates) and dizziness (more common with ACE inhibitors).

Administer or teach self-administration of analgesics, as directed, for headache.

Encourage supine position to relieve dizziness (usually associated with a decrease in BP; preload is enhanced by lying supine, thereby providing a temporary increase in BP).

Institute continuous ECG monitoring or obtain 12-lead ECG as directed. Interpret rhythm strip every 4 hours and as needed for patients on continuous monitoring (beta-adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blockers can cause significant bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block).

Evaluate for development of heart failure (beta-adrenergic blockers and some calcium channel blockers have negative inotropic properties).

Obtain daily weight and intake and output.

Auscultate lung fields for crackles and assess for shortness of breath and decrease in oxygen saturation.

Monitor for the presence of edema.

Monitor central venous pressure (CVP), if applicable.

Assess jugular vein distention.

Assess liver engorgement and check liver function studies.

Monitor laboratory tests as indicated (cardiac markers).

Monitor for poor perfusion.

Be sure to remove previous nitrate patch or paste before applying new paste or patch (prevents hypotension) and to reapply on different body site. To decrease nitrate tolerance, transdermal nitroglycerin may be worn only in the day-time hours and taken off at night when physical exertion is decreased.

Be alert to adverse reaction related to abrupt discontinuation of beta-adrenergic blocker and calcium channel blocker therapy. These drugs must be tapered to prevent a “rebound phenomenon”: tachycardia, increase in chest pain, hypertension.

Discuss use of chromotherapeutic therapy with health care provider (tailoring of anti-anginal drug therapy to the timing of circadian events).

Report adverse drug effects to health care provider.

Decreasing Anxiety

Rule out physiologic etiologies for increasing or new-onset anxiety before administering as-needed sedatives. Physiologic causes must be identified and treated in a timely fashion to prevent irreversible adverse or even fatal outcomes; sedatives may mask symptoms delaying timely identification and diagnosis and treatment.

Assess patient for signs of hypoperfusion, auscultate heart and lung sounds, obtain a rhythm strip, and administer oxygen, as prescribed. Notify the health care provider immediately.

Document all assessment findings, health care provider notification and response, and interventions and response.

Explain to patient and family reasons for hospitalization, diagnostic tests, and therapies administered.

Encourage patient to verbalize fears and concerns about illness through frequent conversations—conveys to patient a willingness to listen.

Answer patient’s questions with concise explanations.

Administer medications to relieve patient’s anxiety as directed. Sedatives and tranquilizers may be used to prevent attacks precipitated by aggravation, excitement, or tension.

Explain to patient the importance of anxiety reduction to assist in control of angina. (Anxiety and fear put increased stress on the heart, requiring the heart to use more oxygen.) Teach relaxation techniques.

Discuss measures to be taken when an anginal episode occurs. (Preparing patient decreases anxiety and allows patient to describe angina accurately.)

Patient Education and Health Maintenance

Instruct Patient and Family about CAD

Assess readiness to learn (pain free, shows interest, and comfortable), learning style, cognition, and education level.

Review the chambers of the heart and the coronary artery system, using a diagram of the heart.

Show patient a diagram of a clogged artery; explain how the blockage occurs; point out on the diagram the location of patient’s lesions.

Explain what angina is (a warning sign from the heart that there is not enough blood and oxygen because of the blocked artery or spasm).

Review specific risk factors that affect CAD development and progression; highlight those risk factors that can be modified and controlled to reduce risk.

Discuss the signs and symptoms of angina, precipitating factors, and treatment for attacks. Stress to patient the importance of treating angina symptoms at once.

Distinguish for patient the different signs and symptoms associated with stable angina versus preinfarction angina.

Give patient and family handouts to review and encourage questions for a later teaching session.

Identify Suitable Activity Level to Prevent Angina

Advise the patient about the following:

Participate in a normal daily program of activities that do not produce chest discomfort, shortness of breath, and undue fatigue. Spread daily activities out over the course of the day; avoid doing everything at one time. Begin regular exercise regimen, as directed by health care provider.

Avoid activities known to cause anginal pain—sudden exertion, walking against the wind, extremes of temperature, high altitude, and emotionally stressful situations, which my accelerate heart rate, raise BP, and increase cardiac workload.

Refrain from engaging in physical activity for 2 hours after meals. Rest after each meal, if possible.

Do not perform activities requiring heavy effort (eg, carrying heavy objects).

Try to avoid cold weather, if possible; dress warmly and walk more slowly. Wear scarf over nose and mouth when in cold air.

Lose weight, if necessary, to reduce cardiac load.

Instruct patient that sexual activity is not prohibited and should be discussed with health care provider.

Instruct about Appropriate Use of Medications and Adverse Effects

Carry nitroglycerin at all times.

Nitroglycerin is volatile and is inactivated by heat, moisture, air, light, and time.

Keep nitroglycerin in original dark glass container, tightly closed to prevent absorption of drug by other pills or pillbox.

Nitroglycerin should cause a slight burning or stinging sensation under the tongue when it is potent.

Place nitroglycerin under the tongue at first sign of chest discomfort.

Stop all effort or activity, sit, and take nitroglycerin tablet—relief should be obtained in a few minutes.

Repeat dosage in 5 minutes for total of three tablets if relief is not obtained.

Keep a record of the number of tablets taken to evaluate change in anginal pattern.

Take nitroglycerin prophylactically to avoid pain known to occur with certain activities.

Demonstrate for patient how to administer nitroglycerin paste correctly.

Place paste on calibrated strip.

Remove previous paste on skin by wiping gently with tissue. Be careful to avoid touching paste to fingertips as this will lead to increased dosing from absorption.

Rotate site of administration to avoid skin irritation.

Apply paste to skin; use plastic wrap to protect clothing if not provided on strip.

Have patient return demonstration.

Instruct patient on administration of transdermal nitroglycerin patches.

Remove previous patch; fold in half so that medication does not touch fingertips and will not be accessible in trash. Wipe area with tissue to remove any residual medication.

Apply patch to a clean, dry, nonhairy area of body.

Rotate administration sites.

Instruct patient not to remove patch for swimming or bathing.

If patch loosens and part of it becomes nonadherent, it should be folded in half and discarded. A new patch should be applied.

Teach patient about potential adverse effects of other medications. Instruct patient not to stop taking any of these without discussing with health care provider.

Constipation—verapamil.

Ankle edema—nifedipine.

Heart failure (shortness of breath, weight gain, edema)— beta-adrenergic blockers or calcium channel blockers.

Dizziness—vasodilators, antihypertensives.

Impotence-decreased libido and sexual functioning— beta-adrenergic blockers

Ensure that patient has enough medication until next follow-up appointment or trip to the pharmacy. Warn against abrupt withdrawal of beta-adrenergic blockers or calcium channel blockers to prevent rebound effect.

Counsel on Risk Factors and Lifestyle Changes

Inform patient of methods of stress reduction, such as biofeedback and relaxation techniques.

Review low-fat and low-cholesterol diet. Explain AHA guidelines (see www.heart.org), which recommend eating fish at least twice per week, especially fish high in omega-3 oils.

Omega-3 oils have been shown to improve arterial health and decrease BP, triglycerides, and the growth of atherosclerotic plaque.

Omega-3 oils can be found in fatty fish, such as mackerel, salmon, sardines, herring, and albacore tuna.

Suggest available cookbooks (AHA) that may assist in planning and preparing foods.

Have patient meet with dietitian to design a menu plan.

Inform patient of available cardiac rehabilitation programs that offer structured classes on exercise, smoking cessation, and weight control.

Instruct patient to avoid excessive caffeine intake (coffee, cola drinks), which can increase the heart rate and produce angina.

Tell patient not to use “diet pills,” nasal decongestants, or any over-the-counter (OTC) medications that can increase heart rate or stimulate high BP.

Encourage patient to avoid alcohol or drink only in moderation (alcohol can increase hypotensive adverse effects of drugs).

Encourage follow-up visits for control of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Have patient discuss supplement therapy (ie, vitamins B6, B12, C, E, folic acid, and L-arginine) with health care provider.

For additional information, refer patient to the AHA (www. americanheart.org).

Refer patient to health care provider to discuss the use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors (PDe5) for erectile dysfunction.

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

Verbalizes relief of pain.

BP and heart rate stable.

Verbalizes lessening anxiety, ability to cope.

Myocardial Infarction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is one of the manifestations of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and refers to a dynamic process by which one or more regions of the heart experience a prolonged decrease or cessation in oxygen supply because of insufficient coronary blood flow; subsequently, necrosis or “death” to the affected myocardial tissue occurs. The onset of the MI process may be sudden or gradual, and the progression of the event to cell death takes approximately 3 to 6 hours. MI is one manifestation of ACS.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Acute coronary thrombosis (partial or total)—associated with 90% of MIs.

Severe atherosclerosis (>70% narrowing of the artery) precipitates thrombus.

Thrombus formation begins with plaque rupture and platelets’ adhesion to the damaged area.

Activation of the exposed platelets causes expression of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors that bind fibrinogen.

Further platelet aggregation and adhesion occurs, enlarging the thrombus and occluding the artery.

Other etiologic factors include coronary artery spasm, coronary artery embolism, infectious diseases causing arterial inflammation, hypoxia, anemia, and severe exertion or stress on the heart in the presence of significant CAD (ie, surgical procedures, shoveling snow).

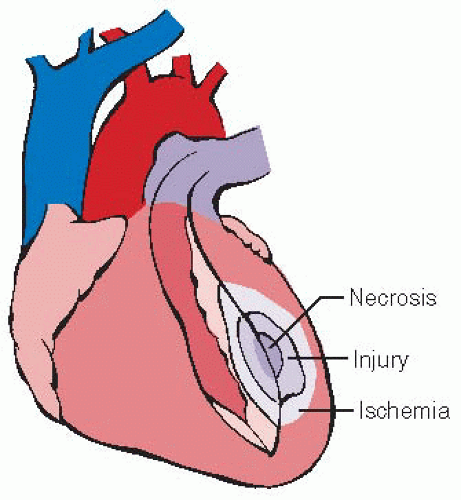

Different degrees of damage occur to the heart muscle (see

Figure 13-2):

Zone of necrosis—death to the heart muscle caused by extensive and complete oxygen deprivation; irreversible damage.

Zone of injury—region of the heart muscle surrounding the area of necrosis; inflamed and injured, but still viable if adequate oxygenation can be restored.

Zone of ischemia—region of the heart muscle surrounding the area of injury, which is ischemic and viable; not endangered unless extension of the infarction occurs.

Classification of MI:

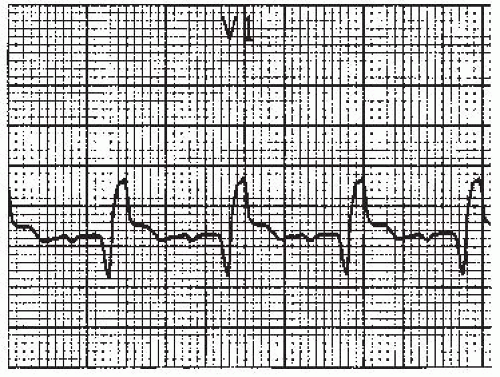

STEMI—whereby ST-segment elevations are seen on ECG. The area of necrosis may or may not occur through the entire wall of heart muscle.

NSTEMI—no ST-segment elevations can be seen on ECG. ST depressions may be noted as well as positive cardiac markers, T-wave inversions, and clinical equivalents (chest pain). Area of necrosis may or may not occur through the entire myocardium.

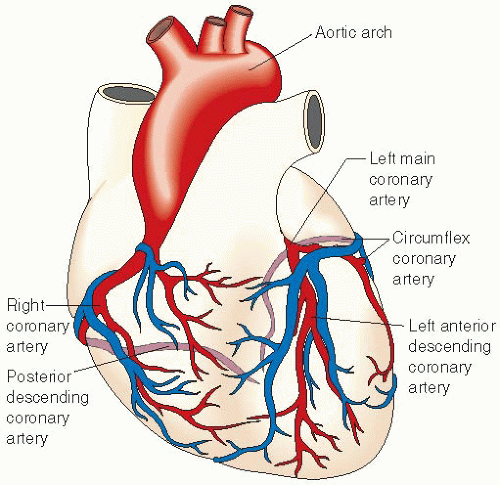

The region(s) of the heart muscle that becomes affected depends on which coronary artery(ies) is/are obstructed (see

Figure 13-3).

Left ventricle is a common and dangerous location for an MI because it is the main pumping chamber of the heart. The left anterior descending artery supplies oxygen to this part of the heart.

Right ventricular infarctions commonly occur with damage to the inferior and/or posterior wall of the left ventricle. Occlusion in the right coronary or circumflex arteries can lead to this type of infarct.

The severity and location of the MI determines prognosis.

Clinical Manifestations

Chest pain.

Severe, diffuse, steady substernal pain; may be described as crushing, squeezing, or dull.

Not relieved by rest or sublingual vasodilator therapy such as nitroglycerine, but requires opioids (ie, morphine).

May radiate to the arms (usually the left), shoulders, neck, back, and/or jaw.

Continues for more than 15 minutes.

May produce anxiety and fear, resulting in increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate.

Some patients, women or diabetics, may exhibit no complaints of pain (silent MI).

Diaphoresis; cool, clammy skin; facial pallor.

Hypertension or hypotension.

Bradycardia or tachycardia.

Premature ventricular and/or atrial beats.

Palpitations, severe anxiety, dyspnea.

Disorientation, confusion, restlessness.

Fainting, marked weakness.

Nausea, vomiting, hiccups.

Atypical symptoms: epigastric or abdominal distress, dull aching or tingling sensations, shortness of breath, extreme fatigue.

Diagnostic Evaluation

ECG Changes

Generally occurs within 2 to 12 hours, but may take 72 to 96 hours.

Necrotic, injured, and ischemic tissues alter ventricular depolarization and repolarization.

Location of the infarction (anterior, anteroseptal, inferior, posterior, lateral) is determined by the leads in which the ST changes (elevation vs. depression) are seen. Of note, the changes must be in two contiguous or related leads to be diagnostic.

Cardiac Markers

Cardiac enzymes (biochemical markers) are not diagnostic of an acute MI with a single elevation; serial markers are drawn (see

page 328).

Other Findings

Elevated CRP and lipoprotein(s) due to inflammation in the coronary arteries.

Abnormal coagulation studies (prothrombin time [PT], partial thromboplastin time [PTT]).

Elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and sedimentation rate due to the inflammatory process involved in heart muscle cell damage.

Radionuclide imaging allows recognition of areas of decreased perfusion.

PET determines the presence of reversible heart muscle injury and irreversible or necrotic tissue; extent to which the injured heart muscle has responded to treatment can also be determined.

Cardiac muscle dysfunction noted on echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Management

The ACCF/AHA (2011) issued “Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina and Non-ST-Elevation MI.” These guidelines call for clinicians to begin treatment for acute chest pain immediately, based on risk level and ECG changes, rather than waiting for cardiac marker results, which was the traditional approach to diagnosis and treatment of MI.

The goals for UA/NSTEMI therapy are immediate relief of ischemia and prevention of severe outcomes such as death or myocardial infarction or reinfarction. To achieve this requires administration of anti-ischemic therapy (ie, rest, supplemental oxygen, nitroglycerin, beta blockers, ACE inhibitors); antithrombotic therapy (ie, aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine); and ongoing risk stratification and use of invasive procedure (ie, cardiac catheterization) to provide early restoration of coronary blood flow.

Pharmacologic Therapy

The pharmacologic therapy for MI is standard (see

Table 13.1, page 390). Use the MONA acronym to outline immediate pharmacologic interventions.

M (morphine)—IV rather than intramuscular (I.M.) administration to prevent spurious elevation in serial biomarkers. Used to treat chest pain. Endogenous catecholamine release during pain imposes an increase in the workload on the heart, thus causing an increase in oxygen demand. Morphine’s analgesic effects decrease the pain, relieve anxiety, and improve cardiac output by reducing preload and afterload.

O (oxygen)—given via nasal cannula or face mask. Increases oxygenation to ischemic heart muscle.

N (nitrates)—given sublingually via spray or through IV administration. Vasodilator therapy reduces preload by decreasing blood return to the heart and decreasing oxygen demand.

A (aspirin)—immediate dosing by mouth (chewed) is recommended to halt platelet aggregation.

Other Medications

Fibrinolytic agents such as tissue plasma activator, streptokinase, and reteplase reestablish blood flow in coronary vessels by dissolving thrombus.

Anti-arrhythmics, such as amiodarone, and correction of electrolyte imbalances decrease the ventricular irritability that occurs after MI.

Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

Surgical Revascularization

Cardiac surgery (ie, CABG) following STEMI is associated with high mortality in the first 3 to 7 days, thus the benefit of revascularization must be weighed against the risk of cardiac surgery.

Benefits of this therapy include definitive treatment of the stenosis and less scar formation on the heart.

Nursing Assessment

Gather information regarding the patient’s chest pain:

Nature and intensity—describe the pain in patient’s own words and compare it with pain previously experienced.

Onset and duration—exact time pain occurred as well as the time pain relieved or diminished (if applicable).

Location and radiation—point to the area where the pain is located and to other areas where the pain seems to travel.

Precipitating and aggravating factors—describe the activity performed just before the onset of pain and if any maneuvers and/or medications alleviated the pain.

Question patient about other symptoms experienced associated with the pain. Observe patient for diaphoresis, facial pallor, dyspnea, guarding behaviors, rigid body posture, extreme weakness, and confusion.

Evaluate cognitive, behavioral, and emotional status.

Question patient about prior health status with emphasis on current medications, allergies (opiate analgesics, iodine, shellfish), recent trauma or surgery, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) ingestion, peptic ulcers, fainting spells, drug and alcohol use.

Analyze information for contraindications for fibrinolytic therapy and PCI.

Gather information about presence or absence of cardiac risk factors.

Identify patient’s social support system and potential caregivers.

Identify significant others’ reaction to the crisis situation.

Nursing Diagnoses

Anxiety related to chest pain, fear of death, threatening environment.

Activity Intolerance related to insufficient oxygenation to perform activities of daily living, deconditioning effects of bed rest.

Risk for Injury (bleeding) related to dissolution of protective clots.

Risk for Decreased Cardiac Tissue Perfusion related to coronary restenosis, extension of infarction.

Ineffective Coping related to threats to self-esteem, disruption of sleep-rest pattern, lack of significant support system, loss of control, and change in lifestyle.

Nursing Interventions

Alleviating Anxiety

Rule out physiologic etiologies for increasing or new-onset anxiety before administering as-needed sedatives. Physiologic causes must be identified and treated in a timely fashion to prevent irreversible adverse or even fatal outcomes; sedatives may mask symptoms, delaying timely identification, diagnosis, and treatment.

Autonomic signs of anxiety are increases in heart rate, BP, respiratory rate, and tremulousness, but they may also be signs of physiologic complications.

Anxiety with dyspnea, tachypnea, and tachycardia may indicate pulmonary embolism; frothy pink sputum and orthopnea indicate pulmonary edema.

Appearance of heart murmurs or friction rub indicates valvular dysfunction, possible intraventricular septal rupture, and pericarditis.

Whenever anxiety increases, assess patient for signs of hypoperfusion, auscultate heart and lung sounds, obtain a rhythm strip, and administer oxygen, as prescribed. Notify the health care provider immediately.

Assess and document emotional status frequently. Document all assessment findings, health care provider notification and response, and interventions and response.

Explain to patient and family reasons for hospitalization, diagnostic tests, and therapies administered.

Explain equipment, procedures, and need for frequent assessment to patient and significant others.

Discuss with patient and family the anticipated nursing and medical regimen.

Administer anti-anxiety agents, as prescribed.

Explain to patient the reason for sedation: undue anxiety can make the heart more irritable and require more oxygen.

Assure patient that the goal of sedation is to promote comfort and, therefore, should be requested if anxious, excitable, or “jittery” feelings occur.

Observe for adverse effects of sedation, such as lethargy, confusion, and/or increased agitation.

Maintain consistency of care with one or two nurses regularly assisting patient, especially if severe anxiety is present.

Offer massage, imagery, and progressive muscle relaxation to promote relaxation, reduce muscle tension, and reduce workload on the heart.

Increasing Activity Tolerance

Promote activity tolerance with early gradual increase in mobilization—prevents deconditioning, which occurs with bed rest.

Minimize environmental noise.

Provide a comfortable environmental temperature.

Avoid unnecessary interruptions and procedures.

Structure routine care measures to include rest periods after activity.

Discuss with patient and family the purpose of limited activity and visitors—to help the heart heal by lowering heart rate and BP, maintaining cardiac workload at lowest level, and decreasing oxygen consumption.

Promote restful diversional activities for patient (reading, listening to music, drawing, crossword puzzles, crafts).

Encourage frequent position changes while in bed.

Assist patient with prescribed activities.

Assist patient to rise slowly from a supine position to minimize orthostatic hypotension related to medications.

Encourage passive and active range-of-motion (ROM) exercise as directed while on bed rest.

Measure the length and width of the unit so patients can gradually increase their activity levels with specific guidelines (walk one width [150 ft] of the unit).

Elevate patient’s feet when out of bed in chair to promote venous return.

Implement a step-by-step program for progressive activity, as directed. Typically can progress to the next step if they are free from chest pain and ECG changes during the activity.

Preventing Bleeding

Take vital signs every 15 minutes during infusion of fibrinolytic agent and then hourly.

Observe for hematomas or skin breakdown, especially in potential pressure areas such as the sacrum, back, elbows, ankles.

Be alert to verbal complaints of back pain indicative of possible retroperitoneal bleeding.

Observe all puncture sites every 15 minutes during infusion of fibrinolytic therapy and then hourly for bleeding.

Apply manual pressure to venous or arterial sites if bleeding occurs. Use pressure dressings for coverage of all access sites.

Observe for blood in stool, emesis, urine, and sputum.

Minimize venipunctures and arterial punctures; use heparin lock for blood sampling and medication administration.

Avoid I.M. injections.

Caution patient about vigorous tooth brushing, hair combing, or shaving.

Avoid trauma to patient by minimizing frequent handling of patient.

Monitor laboratory values: PT, International Normalized Ratio, PTT, hematocrit (HCT), and hemoglobin.

Check for current blood type and crossmatch.

Administer antacids or GI prophylaxis, as directed, to prevent stress ulcers.

Implement emergency interventions, as directed, in the event of bleeding: fluid, volume expanders, blood products.

Monitor for changes in mental status and headache.

Avoid vigorous oral suctioning.

Avoid use of automatic BP device above puncture sites or hematoma. Use care in taking BP; use arm not being used for fibrinolytic therapy.

Maintaining Cardiac Tissue Perfusion

Observe for persistent and/or recurrence of signs and symptoms of ischemia, including chest pain, diaphoresis, hypotension—may indicate extension of MI and/or reocclusion of coronary vessel.

Report immediately.

Administer oxygen, as directed.

Record a 12-lead ECG.

Prepare patient for possible emergency procedures: cardiac catheterization, bypass surgery, PCI, fibrinolytic therapy, intra-aortic balloon pump.

Strengthening Coping Abilities

Listen carefully to patient and family to ascertain their cognitive appraisals of stressors and threats.

Assist patient to establish a positive attitude toward illness and progress adaptively through the grieving process.

Manipulate environment to promote restful sleep by maintaining patient’s usual sleep patterns.

Be alert to signs and symptoms of sleep deprivation—irritability, disorientation, hallucinations, diminished pain tolerance, aggressiveness.

Minimize possible adverse emotional response to transfer from the intensive care unit to the intermediate care unit:

Introduce the admitting nurse from the intermediate care unit to the patient before transfer.

Plan for the intermediate care nurse to answer questions the patient may have and to inform patient what to expect relative to physical layout of unit, nursing routines, and visiting hours.

Patient Education and Health Maintenance

Goals are to restore patient to optimal physiologic, psychological, social, and work level; to aid in restoring confidence and self-esteem; to develop patient’s self-monitoring skills; to assist in managing cardiac problems; and to modify risk factors.

Inform the patient and family about what has happened to patient’s heart.

Explain basic cardiac anatomy and physiology.

Identify the difference between angina and MI.

Describe how the heart heals and that healing will not be complete for 6 to 8 weeks after infarction.

Discuss what the patient can do to assist in the recovery process and reduce the chance of future heart attacks.

Instruct patient on how to judge the body’s response to activity.

Introduce the concept that different activities require varying expenditures of oxygen.

Emphasize the importance of rest and relaxation alternating with activity.

Instruct patient how to take pulse before and after activity as well as guidelines for the acceptable increases in heart rate that should occur.

Review signs and symptoms indicative of a poor response to increased activity levels: chest pain, extreme fatigue, shortness of breath.

Design an individualized activity progression program for patient as directed.

Determine activity levels appropriate for patient, as prescribed, and by predischarge low-level exercise stress test.

Encourage patient to list activities he or she enjoys and would like to resume.

Establish the energy expenditure of each activity (ie, which are most demanding on the heart) and rank activities from lowest to highest.

Instruct patient to move from one activity to another after the heart has been able to manage the previous workload as determined by signs and symptoms and pulse rate.

Give patient specific activity guidelines and explain that activity guidelines will be reevaluated after heart heals.

Walk daily, gradually increasing distance and time, as prescribed.

Avoid activities that tense muscles, such as weightlifting, lifting heavy objects, isometric exercises, pushing and/or pulling heavy loads, all of which can cause vagal stimulation.

Avoid working with arms overhead.

Gradually return to work.

Avoid extremes in temperature.

Do not rush; avoid tension.

Advise getting at least 7 hours of sleep each night and taking 20- to 30-minute rest periods twice per day.

Advise limiting visitors to three to four daily for 15 to 30 minutes and shorten phone conversations.

Tell patient that sexual relations may be resumed on advice of health care provider, usually after exercise tolerance is assessed.

If patient can walk briskly or climb two flights of stairs, can usually resume sexual activity; resumption of sexual activity parallels resumption of usual activities.

Sexual activity should be avoided after eating a heavy meal, after drinking alcohol, or when tired.

Discuss impotence as an adverse effect of drug therapy and phosphodiesterase contraindications.

Advise eating three to four small meals per day rather than large, heavy meals. Rest for 1 hour after meals.

Advise limiting caffeine and alcohol intake.

Driving a car must be cleared with health care provider at a follow-up visit.

Teach patient about medication regimen and adverse effects.

Instruct the patient to call 911 when chest pressure or pain not relieved in 5 minutes by nitroglycerin or rest.

Instruct the patient to notify health care provider when the following symptoms appear:

Assist patient to reduce risk of another MI by risk factor modification.

For additional information and support, refer patient to AHA (www.americanheart.org) and the ACC (www.acc.org).

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

No signs of anxiety or agitation.

Activity slowly progressing and tolerated well.

No signs of bleeding.

No recurrent chest pain.

Sleeps well; emotionally stable.

Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia is a group of metabolic abnormalities resulting in combinations of elevated serum cholesterol. Total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) are two of the major lipids in the body. They are transported through the bloodstream by lipoproteins. Lipoproteins are made up of a phospholipid and specific proteins called apoproteins or apo lipoproteins. There are five main classes of lipoproteins:

Chylomicrons

Very low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs)

Intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDLs)

Low-density lipoproteins (LDLs)

High-density lipoproteins (HDLs)

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Primary Hyperlipidemias

Genetic metabolic abnormalities resulting in the overproduction or underproduction of specific lipoproteins or enzymes. They tend to be familial.

Primary hyperlipidemias include hypercholesterolemia, defective apolipoproteinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, combined hyperlipidemia, dysbetalipoproteinemia, polygenic hypercholesterolemia, lipoprotein lipase deficiency, apoprotein C-II deficiency, lethicin cholesterol acetyltransferase deficiency.

Secondary Hyperlipidemias

Very common and are multifactorial.

Etiologic factors include chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, and liver disease.

Other etiologic factors are obesity, dietary intake, pregnancy, alcoholism.

Medications include beta-adrenergic blockers, alpha-adrenergic blockers, diuretics, glucocorticoid and anabolic steroids, and estrogen preparations.

Consequences

Atherosclerotic plaque formation in blood vessels.

Causes narrowing, possible ischemia, and may lead to thromboembolus formation.

Result in cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease.

Clinical Manifestations

Usually asymptomatic until significant target organ damage is done.

May be metabolic signs, such as corneal arcus, xanthoma, xanthelasma, pancreatitis.

Chest pain, MI.

Carotid bruit, transient ischemic attacks, stroke.

Intermittent claudication, arterial occlusion of lower extremities, loss of pulses.

Diagnostic Evaluation and Management

The National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines recommend a nine-step process for the diagnosis and treatment of hypercholesterolemia.

Fasting (9 to 12 hours) lipoprotein profile every 5 years for people ages 20 and older, more frequent if abnormal (see

Table 13-2, page 396).

Assess the presence of clinical atherosclerotic disease that confers high risk for CHD events or CHD risk equivalents.

Clinical CHD: history of MI, unstable angina, stable angina, coronary artery procedures, or evidence of clinically significant MI.

CHD risk equivalents: carotid artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, diabetes. (Some experts include chronic renal insufficiency, defined by plasma creatine concentration that exceeds 1.5 mg/dL or an estimated glomerular filtration rate that is less than 60 mL/minute per 1.73 m2.)

Two or more risk factors with 10-year risk for CHD greater than 20%.

Determine presence of major risk factors other than LDL.

Cigarette smoking.

Hypertension (BP ≥140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medications).

Low HDL (<40 mg/dL).

Family history of premature CHD (first-degree relative, male under age 55, female under age 65).

Age (men 45 or older, women 55 or older).

Note: HDL ≥ 60 mg/dL counts as a negative risk factor (its presence removes one risk factor from the total count).

If two or more risk factors (other than LDL) are present without CHD or CHD risk equivalent, assess 10-year CHD risk using Framingham Scoring Method (see www.nhlbi.nih. gov/guidelines/cholesterol/index.htm). There are three levels of 10-year risk:

Determine risk category and subsequent therapy (see

Table 13-3).

Establish LDL goal of therapy.

Determine need for therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLC)

Determine level for drug consideration.

Initiate TLC if LDL is above goal.

Consider adding drug therapy if LDL exceeds levels shown in

Table 13-3.

Identify metabolic syndrome and treat, if present, after 3 months of TLC (see

page 969).

Treat elevated TGs.

Aim for LDL goal, intensify weight management, and increase physical activity.

If TGs are 200 mg/dL or greater after LDL goal is reached, set secondary goal for non-HDL-C (total cholesterol minus HDL) to <130 mg/dL.

If TGs are 200 to 499 mg/dL after LDL goal is reached, consider adding drug if needed to reach non-HDL goal (increase primary drug or add nicotinic acid or fibrate).

If TGs are 500 mg/dL or greater, first lower TGs to prevent pancreatitis.

Very-low-fat diet (15% or fewer calories from fat).

Weight management and physical activity.

Fibrate or nicotinic acid.

When TGs are less than 500 mg/dL, return to LDL-lowering therapy.

Treat low HDL (<40 mg/dL) by first aiming for LDL goal, then intensifying weight management by increasing physical activity. If triglycerides of 200 to 499 mg/dL achieve non-HDL goal and, if triglycerides are <200 mg/dL (isolated low HDL) in CHD or CHD equivalent, consider adding nicotinic acid or fibrate.

Drug Classifications

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are the most effective way to lower elevated LDL and TC. They also raise levels of HDL, lower levels of CRP, and may lower TGs. They can be used alone or in combination with other lipid-lowering drugs.

Require liver function monitoring.

Should not be taken with grapefruit juice; can increase risk of myopathy.

Should not be taken by women who are pregnant, lactating, or plan to get pregnant.

Cholesterol absorption inhibitors—the newest class of lipid-lowering drugs; inhibit intestinal absorption of phytosterols and cholesterol and reduce LDL. Do not require liver function testing if given as monotherapy.

Bile acid sequestrants bind to cholesterol in gut, decreasing absorption Contraindicated in those with history of bile obstruction and phenylketonuria (aspartame-containing agent only).

Nicotinic acid (vitamin B3)—works by inhibiting VLDL secretion, thus decreasing production of LDL. Main adverse effect is severe flushing; however, taking 81 to 325 mg of aspirin beforehand may help. Newer sustained-release forms have fewer adverse effects. Niacin should be avoided in patients with severe peptic disease.

Fibrinic acid derivatives—inhibit synthesis of VLDL, decrease TG, increase HDL. Liver, biliary, or kidney disease— contraindicated.

Other Treatment Considerations

TLC should be considered immediately for all patients with hyperlipidemia and are an important adjunct therapy for patients who receive medications.

Children and adolescents should be considered for screening and treatment of hyperlipidemia if they have positive family history and a family history of obesity. Other indications for screening (in these populations) include being overweight and exhibiting features of metabolic syndrome (hypertension, type 2 diabetes, central adiposity).

Drug therapy is recommended for boys at or older than age 10 and after the onset of menses in girls following a 6- to 12-month dietary trial. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors are the drug class of choice.

Some dietary products may serve as adjunct therapy, such as omega-3 fatty acids, soy protein, plant stanols, and fiber.

Nursing Interventions and Patient Education

Teach diet basics and obtain nutritional consult.

Teach patient to engage in exercise.

Engage patient in smoking-cessation program.

Tell patients that for every 1% increase in HDL, there is a 2% to 3% decrease in risk for CHD.

Explain goal of recommended cholesterol levels. Encourage patients to keep a log of lipid results.

Encourage follow-up laboratory work—repeat lipoprotein analysis and liver function test monitoring every 3 months for those on HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors.

Teach patient taking bile acid sequestrants not to take other medications for 1 hour before or 2 hours after because it prevents absorption of many medications.

For more information on hyperlipidemia and TLC, refer patient to AHA (www.heart.org) or the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute diseases and conditions index (www. nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci).

Evidence Base

Evidence Base NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT Evidence Base

Evidence Base NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERT Evidence Base

Evidence Base

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT GERONTOLOGIC ALERT

GERONTOLOGIC ALERT NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT GERONTOLOGIC ALERT

GERONTOLOGIC ALERT DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERT Evidence Base

Evidence Base