Chapter 28 Candida in HIV infection

Epidemiology

Candidiasis is caused by fungi of the Candida species, which are yeasts that are ubiquitous in the environment. Candida species are common human commensal organisms on skin and mucous membranes; between 30% and 80% of adults and children are colonized with Candida species [1, 2]. The point prevalence of carriage is higher in at-risk groups, such as cancer patients and HIV-infected persons [3–5]. In general, such colonization with Candida does not cause infection. The primary defense mechanisms involved in protection against local infection with Candida involve the cell-mediated immune system. Progressive loss of T-cell function associated with HIV disease leads to an increased risk of direct local invasion of Candida and localized infection. Other host factors important in the defense against Candida infections include blood group secretor status, salivary flow rates, epithelial barrier, antimicrobial constituents of saliva, and the presence of normal bacterial flora. Several studies suggest that HIV infection is associated with impairment in a number of these local mucosal defense mechanisms.

Prior to the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART, or ART), between 50 and 75% of HIV-infected individuals developed at least one episode of mucosal candidiasis. Recurrent episodes are frequent with progressive immune deficiency. The incidence has declined since the introduction of ART in the late 1990s. Higher HIV viral load is significantly associated with increased oral or vaginal colonization and candidiasis, an association that has been reduced by ART [6]. However, in parts of the world where ART is not widely available, mucosal candidiasis continues to represent a significant cause of morbidity. Esophageal candidiasis affects between 10% and 20% of patients with AIDS. Candida infection is the most common cause of esophageal disease in persons with HIV infection.

The majority of cases of candidiasis in the setting of HIV infection are confined to mucosal surfaces i.e. oropharyngeal, esophageal, and vulvovaginal; systemic candidiasis is rare and usually occurs in patients with advanced HIV/AIDS (often in the setting of neutropenia) or occurs as a result of nosocomial acquisition. While oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis are clearly HIV-associated illnesses, it is likely that vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is not. HIV-seropositive women have a higher prevalence of vaginal colonization with Candida compared with seronegative women. However, the incidence of vulvovaginal candidiasis is unrelated to HIV serostatus and tends to reflect other risk factors for vulvovaginal Candida infection such as sexual activity and socioeconomic status. The prevalence of vulvovaginal disease is also independent of CD4 count and does not increase with advancing immunodeficiency. However, the severity and frequency of recurrence of vulvovaginal candidiasis may be linked to progressive HIV infection, and, as a consequence, this remains an important source of morbidity in infected women. This may indicate a difference in pathogenesis of Candidal infection at the two sites, oropharynx and vagina [7].

The most common causative organism is Candida albicans [8], found in over 90% of isolates from patients with their first episode of oropharyngeal candidiasis. In patients with recurrent disease, the same strain causes the relapse in approximately half of cases, but other strains or species may also be implicated. The majority of disease is caused by organisms that are part of the normal flora of an individual, although rare cases of person-to-person transmission have been documented. In patients with prolonged or recurrent antifungal use, non-albicans species with different antimicrobial susceptibilities become more commonly isolated. These include C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, and C. dubliniensis [9, 10]. Some of these species are more likely to be associated with decreased susceptibility to azole antifungals [11].

Clinical Manifestations

Oropharyngeal candidiasis

The differential diagnosis of oropharyngeal candidiasis includes:

1. Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL). OHL is characterized by raised white lesions in the oral mucosa, usually found on the sides of the tongue. It is associated with herpes viruses in the epithelial cells, particularly Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). It can be differentiated from candidiasis by inability to scrape off the plaque or by lack of response to antifungal therapy. Antiviral therapy with acyclovir can be used for treatment, although specific antiviral treatment is not usually required as the condition is typically asymptomatic. OHL is an indication for ART.

2. Oral ulcers. Extensive oral ulceration can be seen in the setting of HIV infection. It has many causes, including herpes simplex virus (HSV) type I and II, cytomegalovirus (CMV), drug toxicities (e.g. Stevens–Johnson syndrome due to co-trimoxazole or antiretrovirals). However, the most common cause is idiopathic aphthous ulceration. Patients typically have single or multiple discrete ulcers that are usually painful and may coalesce or become secondarily infected. Treatment involves identifying the cause and discontinuing the causative agent if relevant. In the case of viral ulceration, systemic antivirals such as acyclovir may be useful. With aphthous ulceration, topical steroids or analgesic mouthwashes are helpful, and oral thalidomide therapy has been shown to be effective in severe cases [12].

3. Gingivitis and periodontitis. Severe oral cavity disease has been seen in HIV infection. It usually presents with painful bleeding gums, halitosis, and dental loosening. There may be ulceration of gums. It is caused by mixed aerobic and anaerobic infection and responds to topical agents; systemic therapy with metronidazole may be required.

4. Kaposi’s sarcoma. When present in the oral cavity, the typical purple lesions of KS are usually seen on the palate. If large, the lesions may ulcerate due to local trauma. Biopsy establishes the diagnosis.

5. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma can cause oral cavity disease in HIV patients. It may present as a mass lesion, tonsillar in origin, or as ulceration of the mucosa. Biopsy establishes the diagnosis.

Disseminated candidiasis and candidemia

In HIV-infected individuals, this is a rare and usually late event, typically occurring in patients with advanced immunosuppression. It is most often a hospital-acquired infection, with non-albicans Candida playing a significant role in pathogenesis. There has been a significant reduction in the incidence of nosocomial candidemia in HIV-infected patients in the post-HAART era [13]. Risk factors are those of nosocomial acquisition, including presence of a central venous catheter, use of gastric acid suppressants, nasogastric tubes, antibiotics, ICU admission [14], severe esophageal mucosal disease, advanced AIDS, concomitant opportunistic infections, non-albicans species, and neutropenia. Virtually every body organ can be affected by Candida infection. Involvement of the eyes (endophthalmitis), central nervous system (meningitis [15], encephalitis), and heart (endocarditis) are described but rare in the setting of HIV infection.

Community-acquired candidemia and disseminated candidiasis in HIV is sometimes seen in countries where injection drug users make up a significant proportion of the HIV-infected population. This can present as end-organ disease such as endocarditis, endophthalmitis or skin lesions [16–18].

Diagnosis

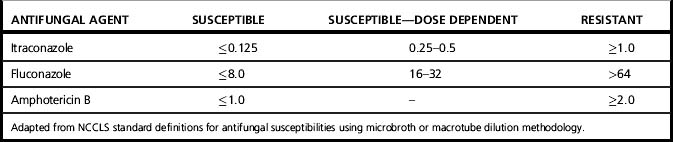

Efforts to develop a standardized reproducible and clinically relevant method of susceptibility testing for yeasts have resulted in development of the NCCLS M27-A2 methodology [19], which has data-driven interpretive breakpoints for susceptibility of Candida spp. to antifungal agents (Table 28.1). Data relating to fluconazole and itraconazole are more readily available than for other antifungals. Susceptibility testing of Candida spp. is not routinely used in most laboratories. The identification of the species is often enough to predict likely antifungal susceptibility, and further testing is not required. However, in the setting of recurrent infection, failure to respond to initial therapy or systemic infection with non-albicans species, susceptibility testing may contribute to clinical decision making and can also be used to support a decision to switch from a parenteral to oral agent. The dose and delivery of the antifungal agent are important in interpreting the data, and host factors play a significant role in the clinical response to a particular agent irrespective of laboratory susceptibility data [20].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree