Cancer Epidemiology

Implications for Prevention, Early Detection, and Treatment

OVERVIEW

Cancer continues to be a significant public health problem in the United States and throughout the world. Each year the American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates the number of new cancer cases and deaths expected in the United States in the current year. This report is an epidemiologic report of cancer in the United States that provides insight into trends in cancer and its care. For example, in 2007 the ACS reported that the number of cancer deaths decreased for the second consecutive year in the United States (Jemal et al., 2007).

Epidemiologists believe that illness, disease, or poor health are not necessarily random events. Some persons have risk factors that place them at risk for development of disease. Thus risk assessment is a significant component of epidemiology. General goals of epidemiology and commonly used epidemiologic terms are shown in the boxes below and on page 4.

TYPES OF EPIDEMIOLOGY

Focus of Epidemiologic Studies

• Determine the extent of disease in a community, region, or defined area.

• Identify potential etiologic sources of a disease and risk factors for the disease.

• Study the natural history of the disease.

• Study the prognosis of the disease with and without treatment or intervention.

• Evaluate both existing and new prevention and treatment measures and methods of health care delivery.

• Examine the cost-effectiveness of various prevention and treatment strategies.

• Provide the basis for public health policy and regulatory decisions regarding health care spending and environmental issues.

Common reasons for using epidemiology in health care. Based on information from Gordis L. (2000). Epidemiology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.

Descriptive Epidemiology

Descriptive epidemiology provides information about the occurrence of disease in a population or its subgroups and trends in the frequency of disease over time. In particular, this entails incidence and mortality rates and survival data. Sources of data include death certificates, cancer registries, surveys, and population censuses (Jennings-Dozier & Foltz, 2002). Descriptive measures are useful for identifying populations and subgroups at high and low risk of disease and for monitoring time trends for specific diseases. They provide the leads for analytic studies designed to investigate factors responsible for such disease profiles. Several common descriptive epidemiologic terms are described.

Incidence.

Incidence refers to the number of new cases of disease that occur during a specified period of time in a defined population at risk for development of the disease (ACS, 2007). Incidence rates also provide information about the risk for development of a disease or condition just by virtue of being a member of a specified population. The ACS publishes projected incidence rates annually for common cancers in its annual Cancer Facts & Figures publication (ACS, 2007).

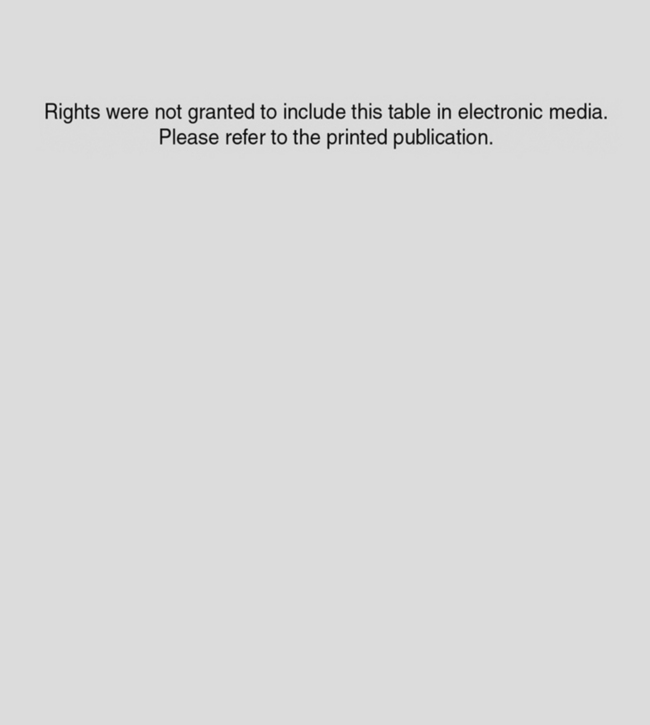

The table on page 5 illustrates that the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the United States for women are cancers of the breast, lung, colon, lymphoma, and melanoma. For men the most commonly diagnosed cancers are cancers of the prostate and lung, lymphoma, and melanoma. The ACS estimates that overall there will be about 1.44 million new cases of cancer in the United States in 2007 (Jemal et al., 2007).

Mortality Rates.

The table on page 5 also shows the projected number of deaths from cancer in the United States. The mortality rate is the number of persons who are estimated to die from a particular cancer during a particular time. The ACS (2007) estimates that approximately 559,650 Americans will die from cancer during 2007. This translates to about 1,500 deaths per day (Jemal et al., 2007). For men, those cancers associated with the highest mortality rates are cancers of the lung, prostate, and colon, and for women the cancers with the highest mortality rates are associated with cancers of the lung, breast, and colon. These four cancers account for half the total cancer deaths among men and women (ACS, 2007).

Many epidemiologists consider the incidence and mortality rates together when making public health decisions. For example, breast cancer affects one in eight women (178,480 new cases) and results in 40,460 deaths annually. It accounts for 26% of new cases of cancer in women and 15% of deaths annually. Compare this with the figures for ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer affects approximately one in 66 women (22,430 new cases) and results in 15,280 deaths annually. Thus it accounts for 3% of new cases of cancer in women but 6% of deaths annually. Examination of these figures suggests that ovarian cancer is either diagnosed at a later stage on average than breast cancer, or treatment is less effective, or both.

Definitions of Terms Used in Cancer Epidemiology

Prevalence: the number of cancers that exist in a defined population at a given point in time

Target population: number of persons in a defined group who are capable of developing the disease and would be appropriate candidates for screening. Population may refer to the general population, or a specific group of people defined by geographic, physical, or social characteristics. For example, nurses who provide cancer genetics counseling need to assess whether a person is of Ashkenazi Jewish background. This special population of Jewish people is at higher risk for three specific mutations for hereditary breast cancer (Struewing et al., 1997).

Validity: measure of how well a test measures what it is supposed to measure

Age-Specific Rates.

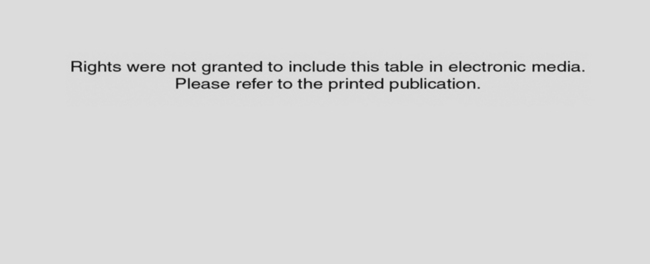

Age-specific rates provide valuable information and insight about how disease risks vary among groups and populations. Often this information is extremely helpful when conveying information about risk to an individual. The table on page 6 provides an example of age-specific rates from the ACS for commonly diagnosed cancers.

Prevalence.

The prevalence of a disease or condition is the proportion of individuals in a specific population who have the disease or condition at a specific point or during a defined period of time. Prevalence includes both newly diagnosed and existing (previously diagnosed or current) cases of a given disease. Cancer prevalence data provide information on the current impact that cancer has on a population and often have implications for the scope of cancer health services needed in a specific community or population.

Estimated New Cancer Cases and Deaths by Sex for All Sites, United States, 2007*

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Source: Estimated new cases are based on 1995–2003 incidence rates from 41 states as reported by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR), representing about 86% of the US population. Estimated deaths are based on data from US Mortality Public Use Data Tapes, 1969 to 2004, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006; From American Cancer Society. (2007). Cancer facts & figures 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

Case-Fatality Rates.

Cancer case-fatality rates are often an important indicator of the effectiveness of a particular cancer detection or treatment method and the impact of the cancer in a defined population. Cancer case-fatality rates provide information about the likelihood of dying from cancer among those diagnosed with the disease (Jennings-Dozier & Foltz, 2002). Case-fatality rates are different than mortality rates in that the mortality rate represents an entire population at risk from dying from a cancer and includes those who do and do not have the cancer. Cancer case-fatality rates include only those who have the disease.

Risk Factor.

A risk factor is a trait or characteristic that is associated with a statistically significant and an increased likelihood of development of a disease (Mahon, 2002). It is important to note, however, that having a risk factor does not mean a person will develop a disease or malignancy, nor does the absence of a risk factor mean one will not develop a disease or malignancy.

Absolute Risk.

Absolute risk is a measure of the occurrence of cancer, either incidence (new cases) or mortality (deaths), in the general population. Absolute risk is helpful when a patient needs to understand what the chances are for all persons in a population having a particular disease. Absolute risk can be expressed either as the number of cases for a specified denominator (e.g., 131 cases of breast cancer per 100,000 women annually) or as a cumulative risk up to a specified age (e.g., one in eight women will develop breast cancer if they live to age 85 years) (ACS, 2007). Another way to express absolute risk is to discuss the average risk of having breast cancer at a certain age. For example, a woman’s risk for development of breast cancer may be 2% at age 50 years but at age 85 years it might be 13%. Risk estimates will be much different for a 50-year-old woman than for an 85-year-old woman because approximately 50% of the cases of breast cancer occur after the age of 65 years. This is illustrated in the table below.

Relative Risk.

The term relative risk refers to a comparison of the incidence or deaths among those with a particular risk factor compared with those without the risk factor. By using relative risk factors, individuals can determine their risk factors and thus better understand their personal chances of development of a specific cancer compared with an individual without such risk factors. If the risk for a person with no known risk factors is 1.0%, the risk for those with known risk factors can be evaluated in relation to this figure.

This can be illustrated by considering several of the relative risk factors for breast cancer. A woman who has her first menstrual period before age 12 years has a 1.3% relative risk for development of breast cancer compared with a woman who has her first menstrual period after age 15 years (Singletary, 2003). For the woman with two first-degree relatives with premenopausal breast cancer, the relative risk is estimated to be 7.1% compared with the woman with no relatives with premenopausal breast cancer. This means she is 7.1 times more likely to develop breast cancer than is the woman without risk factors.

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Source: DevCan: Probability of Developing or Dying of Cancer Software, Version 6.1.0. Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute, 2006. www.srab.cancer.gov/devcan. From American Cancer Society. (2007.) Cancer facts & figures 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree