CHAPTER 6 Calculating parenteral doses

large volume

Introduction

When the fluid balance of the body is compromised by, say, diarrhoea, vomiting or trauma (burns) and the oral route cannot be used, fluids and electrolytes are administered parenterally (Sexton and Rahman 2008).

Intravenous infusions

Special points

Practice aspects

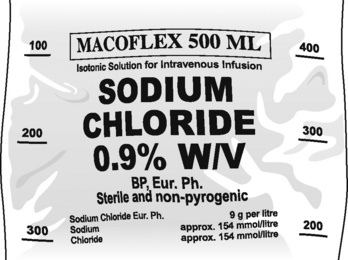

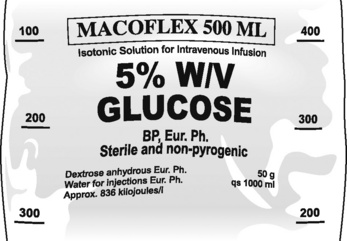

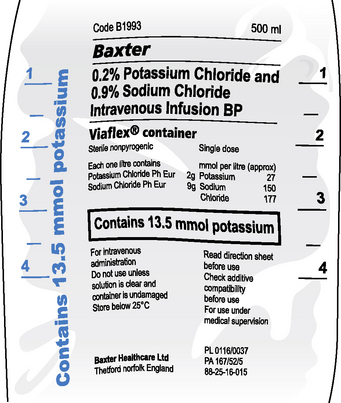

Products

The more common solutions used for intravenous infusion (large volumes) are listed in Table 6.1. The information on a typical infusion solution bag is shown in Figs. 6.1–6.3. Nurses have to be ready to interpret common abbreviations and chemical symbols (see Abbreviations). Normal volumes in containers are 100 mL, 500 mL and 1000 mL.

Table 6.1 Common infusion solutions

| Active ingredient of solution | Content and common strengths w/v | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose (dextrose anhydrous) | 5% | Commonly used solution to replace water deficit |

| Energy source | ||

| Potassium chloride | Potassium chloride 0.3% or 0.15% with 5% glucose | Used to correct hypokalaemia. In view of dangers of overdose, use ready made up solution rather than add a concentrated solution to an infusion solution. |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Used to control severe metabolic acidosis | |

| Sodium chloride | 0.9% (normal saline) often in combination with glucose and other electrolytes | Used for electrolyte/water imbalance and as a vehicle for drug administration |

| Sodium lactate compound infusion | Sodium chloride, sodium lactate, potassium chloride, calcium chloride (see BNF for details) (BMA and RPSGB 2009) | Used for electrolyte and water deficiency |

* These solutions are hypertonic.

Administration

Infusions are administered using an administration set which conveys the fluid from the bag either to a cannula already sited in a peripheral vein or by central venous access. Administration sets vary depending on whether the infusion is to be administered by gravity or by pump and whether the infusion is of a clear fluid or of blood. It is essential to select the appropriate set as the rate of flow has been predetermined in the different types available.

For adults, the set to use for:

If there is any doubt about which set to use, reference should be made to the administration set packaging.

Gravity-assisted infusion

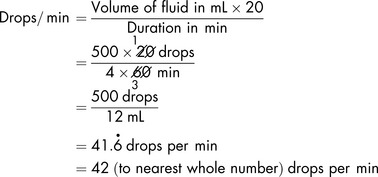

To calculate how to set the infusion at the prescribed rate, you need to know the amount to be infused and the length of time the infusion is to take. The next step is to work out how much will be infused in 1 hour. This is done by dividing the total volume by the time the infusion is to take:

For example, 500 mL of a clear fluid is to be transfused over 4 hours:

The prescribed rate is 125 mL/h.

The infusion can be controlled at 42 drops per minute.

Pump-assisted infusion

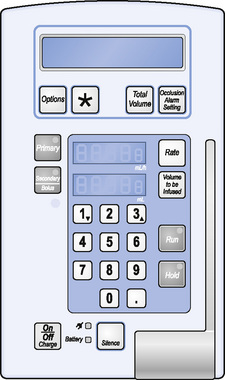

When using an infusion pump (Fig. 6.4), the appropriate administration set (specifically for use with a pump) must be used.

Once the calculation has been made, and only then, the rate and the total volume to be infused can be keyed in to the pump.

If a volume of 1000 mL is to be infused over 8 hours, it can be represented as:

The rate is therefore 125 mL per hour.

Reconstitution and dilution of parenteral medicines

Some parenteral medicines may need to be reconstituted, by adding a suitable volume of a diluent and then being further diluted for administration. Often dilution is required because of the irritancy of the drug to the tissues. Whenever possible, dilution to the required strength should be undertaken in a controlled environment (in pharmacy) in order to minimise the risk of microbial contamination. The BNF gives details of any necessary dilutions. The dilution will depend on the method of administration (Table 6.2), i.e.:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree