C

Cardiomyopathy

Description

Cardiomyopathy (CMP) is a group of diseases that directly affect myocardial structure or function. CMP can be classified as primary or secondary:

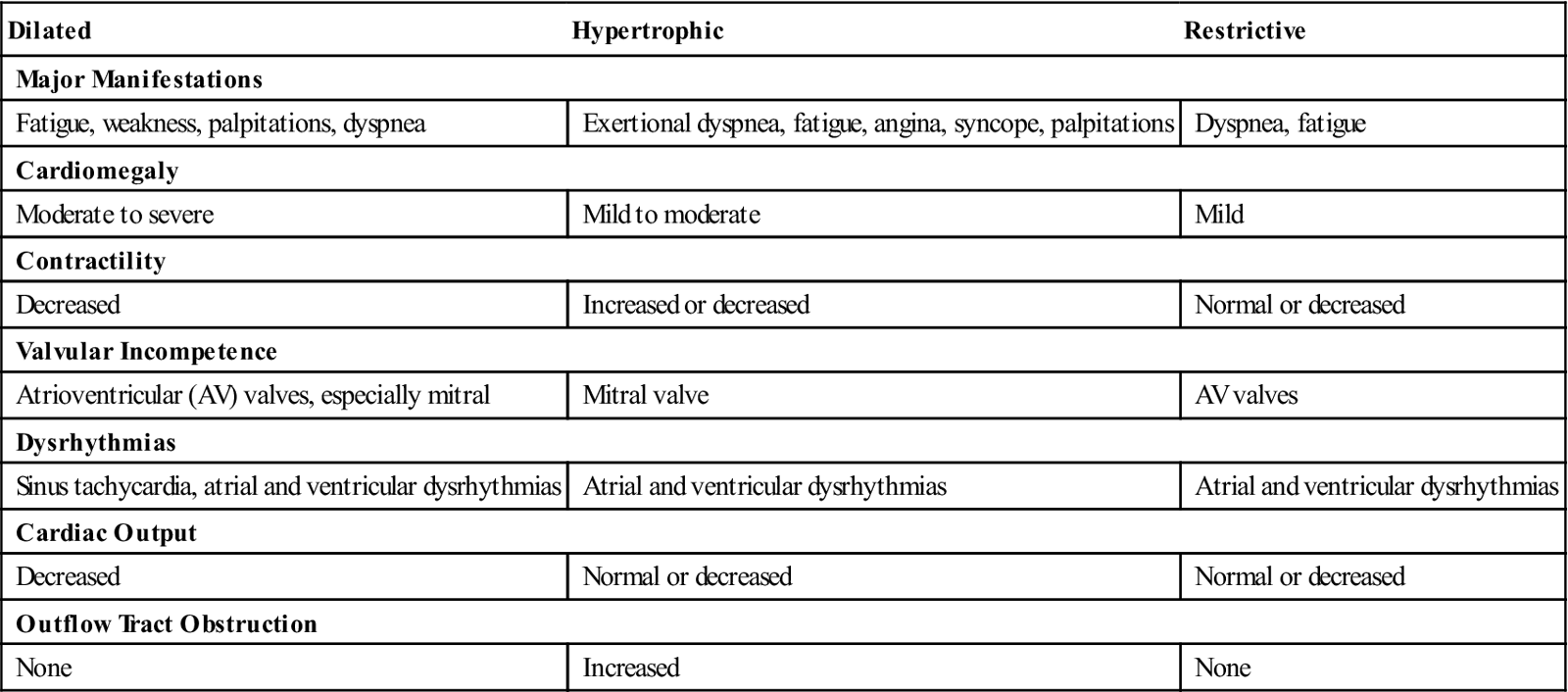

Three major types of CMP are dilated, hypertrophic, and restrictive. Each type has its own pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and treatment protocols (Table 21). CMP can lead to cardiomegaly and heart failure (HF). CMP is the primary reason why heart transplants are performed.

Table 21

Comparison of Types of Cardiomyopathy

| Dilated | Hypertrophic | Restrictive |

| Major Manifestations | ||

| Fatigue, weakness, palpitations, dyspnea | Exertional dyspnea, fatigue, angina, syncope, palpitations | Dyspnea, fatigue |

| Cardiomegaly | ||

| Moderate to severe | Mild to moderate | Mild |

| Contractility | ||

| Decreased | Increased or decreased | Normal or decreased |

| Valvular Incompetence | ||

| Atrioventricular (AV) valves, especially mitral | Mitral valve | AV valves |

| Dysrhythmias | ||

| Sinus tachycardia, atrial and ventricular dysrhythmias | Atrial and ventricular dysrhythmias | Atrial and ventricular dysrhythmias |

| Cardiac Output | ||

| Decreased | Normal or decreased | Normal or decreased |

| Outflow Tract Obstruction | ||

| None | Increased | None |

Dilated cardiomyopathy

Pathophysiology

Dilated cardiomyopathy is the most common type of CMP. It is characterized by diffuse inflammation and rapid degeneration of myocardial fibers that results in ventricular dilation, impairment of systolic function, atrial enlargement, and stasis of blood in the left ventricle. The ventricular walls do not hypertrophy.

Clinical manifestations

Signs and symptoms of dilated CMP may develop acutely after a systemic infection or slowly over time. Most people eventually develop HF. Symptoms can include fatigue, dyspnea at rest, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and orthopnea. Dry cough, abdominal bloating, and anorexia may occur as the disease progresses. Signs can include an irregular heart rate with an abnormal S3 and/or S4, pulmonary crackles, edema, pallor, hepatomegaly, heart murmurs, dysrhythmias, and jugular venous distention.

Diagnostic studies

A diagnosis is made on the basis of patient history and exclusion of other causes of HF.

■ Doppler echocardiography is the basis for the diagnosis of dilated CMP.

■ Chest x-ray may show cardiomegaly with pulmonary venous hypertension and pleural effusion.

■ ECG may reveal tachycardia, bradycardia, and dysrhythmias with conduction disturbances.

■ Serum levels of b-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) are elevated in the presence of HF.

Nursing and collaborative management

Interventions focus on controlling HF by enhancing myocardial contractility and decreasing preload and afterload.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Pathophysiology

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is asymmetric left ventricular hypertrophy without ventricular dilation. HCM occurs less commonly than dilated CMP and is more common in men than in women. It is usually diagnosed in young adulthood and is often seen in active, athletic individuals. Hypertrophic CMP is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in otherwise healthy young people.

Clinical manifestations

Patients may be asymptomatic. The most common symptom is dyspnea, which is caused by an elevated left ventricular diastolic pressure. Other manifestations include fatigue, angina, syncope (especially during exertion), and dysrhythmias.

Diagnostic studies

Clinical findings on examination may be unremarkable. The following diagnostic studies may be used:

Nursing and collaborative management

Goals of care are to improve ventricular filling by reducing ventricular contractility and relieving LV outflow obstruction. This can be done with the use of β-adrenergic blockers (e.g., metoprolol) or calcium channel blockers (e.g., verapamil [Calan]).

Nursing interventions focus on relieving symptoms, observing for and preventing complications, and providing emotional support.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy

Pathophysiology

Restrictive cardiomyopathy is the least common type of cardiomyopathic condition. It is a disease of the heart muscle that impairs diastolic filling and stretch.

Clinical manifestations

Classic symptoms of restrictive CMP are fatigue, exercise intolerance, and dyspnea. Other manifestations may include angina, orthopnea, syncope, palpations, and signs of HF.

Diagnostic studies

Chest x-ray may be normal or show cardiomegaly with pleural effusions and pulmonary congestion.

Nursing and collaborative management

Currently, no specific treatment for restrictive CMP exists. Interventions are aimed at improving diastolic filling and the underlying disease process. Treatment includes conventional therapy for HF and dysrhythmias. Heart transplant may also be a consideration.

Nursing care is similar to the care of a patient with HF. As in the treatment of patients with HCM, teach patients to avoid situations such as strenuous activity and dehydration that impair ventricular filling and increase systemic vascular resistance.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Description

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a condition caused by compression of the median nerve, which enters the hand through the narrow confines of the carpal tunnel. The carpal tunnel is formed by ligaments and bones. This condition is often caused by pressure from trauma or edema caused by inflammation of a tendon (tenosynovitis), neoplasm, rheumatoid arthritis, or soft tissue masses such as ganglia. CTS is the most common compression neuropathy in the upper extremities.

■ Women are affected more than men, possibly because of a smaller carpal tunnel.

Clinical manifestations

Manifestations are weakness (especially of the thumb), pain and numbness, impaired sensation in the distribution of the median nerve, and clumsiness in performing fine hand movements. Numbness and tingling may awaken the patient at night. Shaking the hands will often relieve these symptoms. Physical signs of CTS include Tinel’s sign and Phalen’s sign.

In late stages, there is atrophy of the thenar muscles around the base of the thumb, resulting in recurrent pain and eventual dysfunction of the hand.

Nursing and collaborative management

Teach employees and employers about risk factors for CTS to prevent its occurrence. Adaptive devices such as wrist splints may be worn to relieve pressure on the median nerve. Special keyboard pads and mice are available for computer users. Other ergonomic changes include workstation modifications, change in body positions, and frequent breaks from work-related activities.

Early symptoms of CTS can usually be relieved by stopping the aggravating movement and by resting the hand and wrist by immobilizing them in a hand splint. Splints worn at night help keep the wrist in a neutral position and may reduce night pain and numbness. Injection of a corticosteroid drug directly into the carpal tunnel may provide short-term relief.

If symptoms persist for more than 6 months, surgery is generally recommended, which involves severing the band of tissue around the wrist to reduce pressure on the median nerve. Surgery is done in the outpatient setting under local anesthesia. Endoscopic carpal tunnel release is performed through a small puncture incision(s) in the wrist and palm.

■ After surgery, assess the neurovascular status of the hand regularly.

■ Instruct the patient about wound care and the appropriate assessments to perform at home.

Although symptoms may be relieved immediately after surgery, full recovery may take months.

Cataract

Description

A cataract is an opacity within the lens of one or both eyes, causing a gradual decline in vision. Almost 22 million Americans ages 40 years and older have cataracts, and by age 80 more than 50% have cataracts. Cataract removal is the most common surgical procedure in the United States.

Pathophysiology

Although most cataracts are age related (senile cataracts), they can be associated with other factors including trauma, congenital factors such as maternal rubella, radiation or ultraviolet (UV) light exposure, certain drugs such as systemic corticosteroids or long-term topical corticosteroids, and ocular inflammation. The patient with diabetes mellitus tends to develop cataracts at a younger age.

Clinical manifestations

Diagnostic studies

Collaborative care

The presence of a cataract does not necessarily indicate a need for surgery. For many patients the diagnosis is made long before they actually decide to have surgery. Currently no treatment is available to “cure” cataracts other than surgical removal.

Almost all patients have an intraocular lens (IOL) implanted at the time of cataract extraction surgery. Depending on the type of anesthesia, the patient’s eye may be covered with a patch or protective shield, which is usually worn overnight and removed during the first postoperative visit. Most patients experience little visual impairment after surgery. IOL implants provide immediate visual rehabilitation, and many patients achieve a usable level of visual acuity within a few days after surgery.

Nursing management

Goals

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

For the patient who chooses not to have surgery, suggest vision enhancement techniques and a modification of activities and lifestyle to accommodate the visual deficit.

For the patient who elects surgery, provide information, support, and reassurance about the surgical and postoperative experience to reduce or alleviate patient anxiety. Postoperatively, offer mild analgesics for slight scratchiness or mild eye pain. The physician needs to be notified if severe pain, increased or purulent drainage, increased redness, or decreased visual acuity is present.

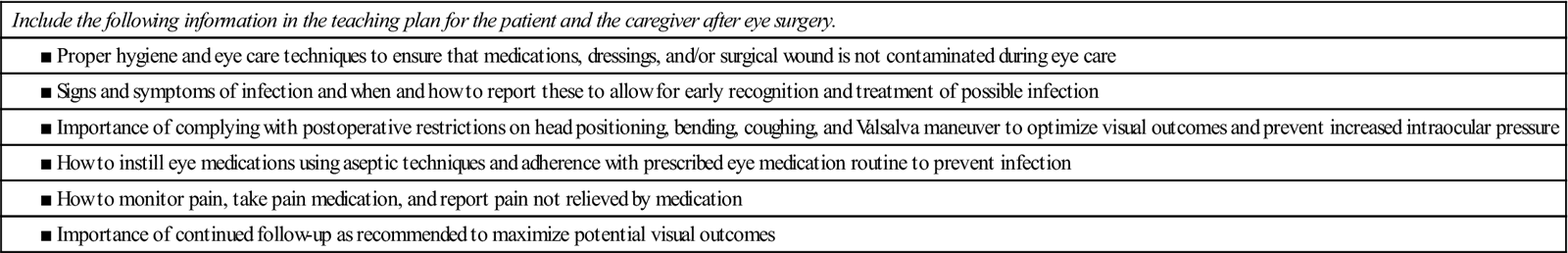

Patient and caregiver teaching

Patient and caregiver teaching

■ Written and verbal discharge teaching should include postoperative eye care, activity restrictions, medications, follow-up visit schedule, and signs of possible complications (Table 22).

Table 22

Patient and Caregiver Teaching Guide

After Eye Surgery

| Include the following information in the teaching plan for the patient and the caregiver after eye surgery. |

Source: Lamb P, Simms-Eaton S: Core curriculum for ophthalmic nursing, ed. 3, Dubuque, Iowa, 2008, Kendall-Hunt.

Celiac disease

Description

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease characterized by damage to the small intestinal mucosa from the ingestion of wheat, barley, and rye in genetically susceptible individuals. It is a relatively common disease that occurs at all ages and has a wide variety of symptoms.

Celiac disease is not the same as the disease tropical sprue, a chronic disorder acquired in tropical areas that is characterized by progressive disruption of jejunal and ileal tissue resulting in nutritional difficulties. Tropical sprue is treated with folic acid and tetracycline.

The incidence of celiac disease is thought to be about 1% of the U.S. population. High-risk groups include first- or second-degree relatives of someone with celiac disease and people with disorders associated with the disease such as migraine and myocarditis. It is slightly more common in women, and symptoms often begin in childhood. Many people seek treatment for nonspecific complaints for years before celiac disease is diagnosed.

Pathophysiology

Three factors necessary for the development of celiac disease are a genetic predisposition, gluten ingestion, and an immune-mediated response.

Clinical manifestations

Classic manifestations of celiac disease include foul-smelling diarrhea, steatorrhea, flatulence, abdominal distention, and symptoms of malnutrition. Some people may instead have atypical symptoms such as decreased bone density and osteoporosis, dental enamel hypoplasia, iron and folate deficiencies, peripheral neuropathy, and reproductive problems.

Diagnostic studies

Celiac disease is confirmed by (1) histologic evidence when a biopsy is taken from the small intestine and (2) the symptoms and histologic evidence disappearing when the person eats a gluten-free diet.

Nursing and collaborative management

Treatment with a gluten-free diet halts the process. Most patients recover completely within 3 to 6 months of treatment, but they need to maintain a gluten-free diet for life. If the disease is untreated, chronic inflammation and hyperplasia continue. Individuals with celiac disease have an increased risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and gastrointestinal cancers.

Patient and caregiver teaching

Patient and caregiver teaching

■ The Celiac Sprue Association website (www.csaceliacs.info) and the Celiac Disease Foundation (www.celiac.org) provide suggestions for maintaining a gluten-free diet and living with celiac disease.

Cervical cancer

Description

Approximately 12,000 women in the United States are diagnosed annually with cervical cancer. Noninvasive cervical cancer (in situ) is about four times more common than invasive cervical cancer.

Pathophysiology

The progression from normal cervical cells to dysplasia and on to cervical cancer appears to be related to repeated injuries to the cervix. The progression occurs slowly over years rather than months. There is a strong relationship between dysplasia and HPV infections. HPV types 16 and 18 together cause about 70% of cervical cancers. Cancer rates are expected to decline further with vaccines (e.g., Gardasil, Cervarix) now being used for the prevention of HPV.

Clinical manifestations

Early cervical cancer is generally asymptomatic, but leukorrhea and intermenstrual bleeding eventually occur.

Diagnostic studies

Collaborative care

Vaccines against HPV reduce the incidence of both cervical-related neoplasia and cervical cancer due to infection from HPV types 16 and 18. Vaccination against HPV is recommended for females and males at ages 11 or 12 years.

The treatment of cervical cancer is guided by the patient’s age, general health, and stage of the tumor (see Table 54-11, Lewis et al, Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1293).

Four procedures can preserve fertility. Conization may be the only therapy needed for noninvasive cervical cancer if analysis of removed tissue indicates that a wide area of normal tissue surrounds the excised tissue. Laser treatments can be used to destroy abnormal tissue. Cautery and cryosurgery may also be used.

Invasive cancer of the cervix is treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation.

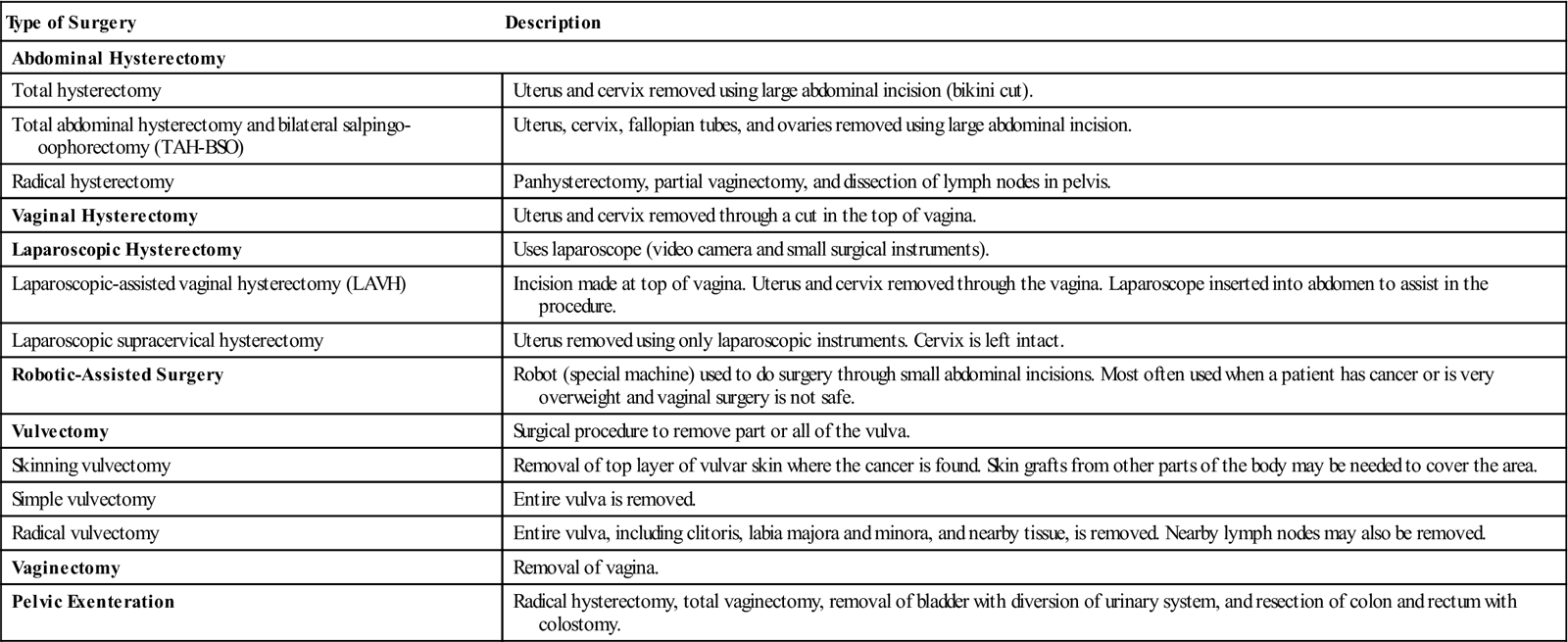

■ Surgical procedures include hysterectomy, radical hysterectomy, and, rarely, pelvic exenteration (Table 23).

■ Cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens benefit patients with cancer spread beyond the cervix.

Table 23

Surgical Procedures Involving the Female Reproductive System

| Type of Surgery | Description |

| Abdominal Hysterectomy | |

| Total hysterectomy | Uterus and cervix removed using large abdominal incision (bikini cut). |

| Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH-BSO) | Uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes, and ovaries removed using large abdominal incision. |

| Radical hysterectomy | Panhysterectomy, partial vaginectomy, and dissection of lymph nodes in pelvis. |

| Vaginal Hysterectomy | Uterus and cervix removed through a cut in the top of vagina. |

| Laparoscopic Hysterectomy | Uses laparoscope (video camera and small surgical instruments). |

| Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) | Incision made at top of vagina. Uterus and cervix removed through the vagina. Laparoscope inserted into abdomen to assist in the procedure. |

| Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy | Uterus removed using only laparoscopic instruments. Cervix is left intact. |

| Robotic-Assisted Surgery | Robot (special machine) used to do surgery through small abdominal incisions. Most often used when a patient has cancer or is very overweight and vaginal surgery is not safe. |

| Vulvectomy | Surgical procedure to remove part or all of the vulva. |

| Skinning vulvectomy | Removal of top layer of vulvar skin where the cancer is found. Skin grafts from other parts of the body may be needed to cover the area. |

| Simple vulvectomy | Entire vulva is removed. |

| Radical vulvectomy | Entire vulva, including clitoris, labia majora and minora, and nearby tissue, is removed. Nearby lymph nodes may also be removed. |

| Vaginectomy | Removal of vagina. |

| Pelvic Exenteration | Radical hysterectomy, total vaginectomy, removal of bladder with diversion of urinary system, and resection of colon and rectum with colostomy. |

Nursing management: Cervical cancer and other cancers of the female reproductive system

In addition to cervical cancer, malignant tumors of the female reproductive system can be found in the endometrium, ovaries, vagina, and vulva. Management of the patient with any cancer of the female reproductive system includes many similar interventions.

Goals

The patient with a malignant tumor of the female reproductive system will actively participate in treatment decisions, achieve satisfactory pain and symptom management, recognize and report problems promptly, maintain preferred lifestyle as long as possible, and continue to practice cancer detection strategies.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

Through your contact with women in a variety of settings, teach women the importance of routine screening for cancers of the reproductive system. Cancer can be prevented when screening reveals precancerous conditions of the vulva, cervix, endometrium, and rarely the ovaries. Assist women to view routine cancer screening as an important self-care activity and recommend vaccination against cervical cancer.

Hysterectomy.

Preoperatively, the patient is prepared for surgery with the standard perineal or abdominal preparation. A vaginal douche and enema may be given according to surgeon preference. The bladder should be emptied before the patient is sent to the operating room. An indwelling catheter is often inserted.

Postoperatively, the patient who has had a hysterectomy will have an abdominal dressing (abdominal hysterectomy) or a sterile perineal pad (vaginal hysterectomy).

The loss of the uterus may bring about grief responses similar to any great personal loss. The ability to bear children may be essential to a woman’s image of being a female. Elicit the woman’s feelings and concerns about her surgery.

Teach the patient what to expect after surgery (e.g., she will not menstruate). Instructions should include specific activity restrictions. Intercourse should be avoided until the wound is healed (about 4 to 6 weeks). If a vaginal hysterectomy is performed, inform the patient that there may be a temporary loss of vaginal sensation.

Salpingectomy and oophorectomy.

Postoperative care of the woman who has undergone removal of a fallopian tube (salpingectomy) or an ovary (oophorectomy) is similar to that for any patient having abdominal surgery. When both ovaries are removed (bilateral oophorectomy), surgical menopause results. Symptoms are similar to those of regular menopause but may be more severe because of the sudden withdrawal of hormones.

Pelvic exenteration.

When other forms of therapy are ineffective in controlling cancer spread and no metastases have been found outside the pelvis, pelvic exenteration may be performed. This radical surgery usually involves removal of the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina, bladder, urethra, and pelvic lymph nodes. In some situations the descending colon, rectum, and anal canal may also be removed. Postoperative care involves that of a patient who has had a radical hysterectomy, an abdominal perineal resection, and an ileostomy or colostomy. Physical, emotional, and social adjustments to life on the part of the woman and her family are great. There are urinary or fecal diversions in the abdominal wall, a reconstructed vagina, and the onset of menopausal symptoms.

Chlamydial infections

Description

Chlamydia trachomatis is a gram-negative bacterium recognized as a genital pathogen responsible for a variety of illnesses. In the United States and Canada, chlamydial infections are the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infection (STI). Infection rates have increased over the past 20 years, with more than 1.3 million cases reported in 2010. This increase may be due in part to better and more intensive screening for the infection. Underreporting is significant because many people are asymptomatic and do not seek testing.

Pathophysiology

Chlamydia can be transmitted during vaginal, anal, or oral sex. Numerous different strains of C. trachomatis cause urogenital infections (e.g., nongonococcal urethritis [NGU] in men and cervicitis in women), ocular trachoma, and lymphogranuloma venereum. As with gonorrhea, chlamydial infections result in a superficial mucosal infection that can become more invasive.

Risk factors include women and adolescents, new or multiple sex partners, sexual partners who have had multiple partners, history of STIs and cervical ectopy, coexisting STIs, and inconsistent or incorrect use of a condom.

Clinical manifestations

Symptoms may be absent or minor in most infected women and many men.

Men

Signs and symptoms in men include urethritis (dysuria, urethral discharge), epididymitis (unilateral scrotal pain, swelling, tenderness, fever), and proctitis (rectal discharge and pain during defecation).

Women

Signs and symptoms in women include cervicitis (mucopurulent discharge and hypertrophic ectopy [area that is edematous and bleeds easily]), urethritis (dysuria, pyuria, and frequent urination), dyspareunia (painful intercourse), bartholinitis (purulent exudate), and menstrual abnormalities.

Complications

Complications often develop from poorly managed, inaccurately diagnosed, or undiagnosed chlamydial infections.

Diagnostic studies

Chlamydial infections in men and women can be diagnosed by urine or collecting swab specimens from the endocervix or vagina (women) and urethra (men). Rectal swab specimens are tested in people engaging in anal sex. Cell culture can be used to detect Chlamydia organisms.

The most common diagnostic tests include the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test, and enzyme immunoassay (EIA). These tests can be used with urine samples rather than urethral and cervical swabs.

Collaborative care

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all sexually active females 25 years of age or younger be routinely screened for Chlamydia. Annual screening of all women older than 25 years of age with one or more risk factors for the infection is also advised.

Doxycycline (Vibramycin) or azithromycin (Zithromax) are used to treat patients and their partners. Treatment of pregnant women usually prevents transmission to the fetus.

The high incidence of recurrence may be due to failure to treat the sexual partners of infected people. Because of the high prevalence of asymptomatic infections, screening of high-risk populations is needed to identify those who are infected.

Nursing management

See Nursing Management: Sexually Transmitted Infections, p. 564.

Cholelithiasis/cholecystitis

Description

The most common disorder of the biliary system is cholelithiasis (stones in the gallbladder). The stones may be lodged in the neck of the gallbladder or in the cystic duct. Cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder) may be acute or chronic, and it is usually associated with cholelithiasis.

Gallbladder disease is a common health problem in the United States. Approximately 8% to 10% of American adults have cholelithiasis.

Pathophysiology

The cause of gallstones is unknown. Cholelithiasis develops when the balance that keeps cholesterol, bile salts, and calcium in solution is altered so that these substances precipitate. Conditions that upset this balance include infection and disturbances in the metabolism of cholesterol. Mixed cholesterol stones, which are predominantly cholesterol, are the most common gallstones.

The stones may remain in the gallbladder or migrate to the cystic duct or common bile duct. They cause pain as they pass through the ducts and may lodge in the ducts and cause obstruction. Stasis of bile in the gallbladder can lead to cholecystitis.

Cholecystitis is most commonly associated with obstruction resulting from gallstones or biliary sludge. Cholecystitis in the absence of obstruction occurs most frequently in older adults and in patients who are critically ill. Bacteria reaching the gallbladder by the vascular or lymphatic route or chemical irritants in the bile can also produce cholecystitis. Escherichia coli, streptococci, and salmonellae are common causative bacteria. Other etiologic factors include adhesions, neoplasms, anesthesia, and opioids.

Clinical manifestations

Cholelithiasis may produce severe symptoms or none at all. Many patients have “silent cholelithiasis.” Severity of symptoms depends on whether the stones are stationary or mobile and whether obstruction is present.

Manifestations of cholecystitis vary from indigestion to moderate to severe pain, fever, and jaundice. Initial symptoms include indigestion and pain and tenderness in the right upper quadrant, which may be referred to the right shoulder and scapula. Pain may be acute and is accompanied by restlessness, diaphoresis, and nausea and vomiting.

Complications

Complications of cholecystitis include gangrenous cholecystitis, subphrenic abscess, pancreatitis, cholangitis (inflammation of biliary ducts), biliary cirrhosis, fistulas, and rupture of the gallbladder, which can produce bile peritonitis.

Diagnostic studies

Collaborative care

The treatment of gallstones in cholelithiasis depends on the stage of disease. Bile acids (cholesterol solvents) such as ursodeoxycholic (ursodiol) and chenodeoxycholic (chenodiol) are used to dissolve stones. ERCP with sphincterotomy (papillotomy) may be used for stone removal. ERCP allows for visualization of the biliary system and placement of stents and sphincterotomy (if warranted).

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) may be used to treat cholelithiasis. In this procedure a lithotriptor uses high-energy shock waves to disintegrate gallstones.

Drug therapy for gallbladder disease includes analgesics, anticholinergics (antispasmodics), fat-soluble vitamins, and bile salts. Morphine may be used initially for pain management. Cholestyramine, which may be used to provide relief from pruritus, is a resin that binds bile salts in the intestine, increasing their excretion in the feces.

During an acute episode of cholecystitis, treatment focuses on pain control, control of possible infection with antibiotics, and maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance. Treatment is mainly supportive and symptomatic. A cholecystostomy may be used to drain purulent material from the obstructed gallbladder.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred surgical procedure for symptomatic cholelithiasis. In this procedure, the gallbladder is removed through one of four small punctures in the abdomen. Most patients experience minimal postoperative pain and are discharged the day of surgery or the day after. In most cases they are able to resume normal activities and return to work within 1 week.

After surgery people have fewer problems if they eat smaller, more frequent meals with some fat at each meal to promote gallbladder emptying. If obesity is a problem, a reduced-calorie diet is indicated. The diet should be low in saturated fats and high in fiber and calcium.

Nursing management

Goals

The patient with gallbladder disease will have relief of pain and discomfort, no postoperative complications, and no recurrent attacks of cholecystitis or cholelithiasis.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

Nursing goals for the patient undergoing conservative therapy include relieving pain, relieving nausea and vomiting, providing comfort and emotional support, maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance and nutrition, making accurate assessments to ensure effective treatment, and observing for complications.

The patient with acute cholecystitis or cholelithiasis is frequently experiencing severe pain. Medications ordered to relieve pain should be given as required before it becomes more severe.

Assess what drugs relieve the pain and how much medication is required. Observe for signs of obstruction of the ducts by stones, including jaundice; clay-colored stools; dark, foamy urine; steatorrhea; fever; and increased white blood cell (WBC) count.

Postoperative nursing care after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy includes monitoring for complications such as bleeding, making the patient comfortable, and preparing the patient for discharge.