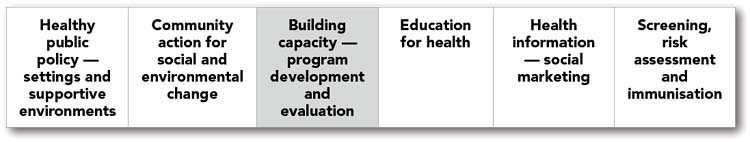

CHAPTER 6 Building capacity for health promotion

program development and evaluation

The continuum of health promotion approaches outlined in Chapter 1 continues to guide health promotion action in this chapter. We continue to work within the socio-environmental approach which fosters community action for social and environmental change to develop and evaluate programs for health enhancement.

WHY DO WE NEED TO PLAN?

The purpose of program-planning is to devise a program that addresses the health issues of concern for the community within the available resources. The Primary Health Care approach ensures that the process and outcome of the planning are acceptable to the community and mindful of social justice, while ensuring the efficiency and effectiveness of the organisation or agency. The fundamental propositions to program development and evaluation are that health and health risks are caused by multiple factors. Efforts to effect environmental and social change must be multidimensional and/or multi-sectoral.

focusing attention on and clarifying what the stakeholders are attempting to do

focusing attention on and clarifying what the stakeholders are attempting to do

allowing for quality and participatory decision-making and better collaboration

allowing for quality and participatory decision-making and better collaboration

knowing what types of interventions are most acceptable and feasible for specific populations and circumstances

knowing what types of interventions are most acceptable and feasible for specific populations and circumstances

taking a multidimensional approach

taking a multidimensional approach

assisting in identifying the resources and activities required

assisting in identifying the resources and activities required

assigning responsibility to specific stakeholders to meet program objectives

assigning responsibility to specific stakeholders to meet program objectives

reducing uncertainty within the program environment

reducing uncertainty within the program environment

informing everyone involved with the program as to the:

informing everyone involved with the program as to the:

reviewing existing practice to assess whether the intervention is meeting a justified need.

reviewing existing practice to assess whether the intervention is meeting a justified need.

The outcome elements of program development are:

understanding the determinants of an issue or problem

understanding the determinants of an issue or problem

ensuring that relevant theory, data and local experience informs the development of the program.

ensuring that relevant theory, data and local experience informs the development of the program.

What is the program development and evaluation planning cycle?

1. Identifying a specific issue, community and focus for a program

The needs assessment — identifying and analysing the health issue:

Specifying the broad purpose of the program:

Converting the analysis of the issue into a draft plan:

Developing roles with key people.

Reviewing available resources.

Ensuring the program is realistic and achievable.

Planning for the organisation of tasks:

Selecting the program strategies.

Preparing materials, resources, activities.

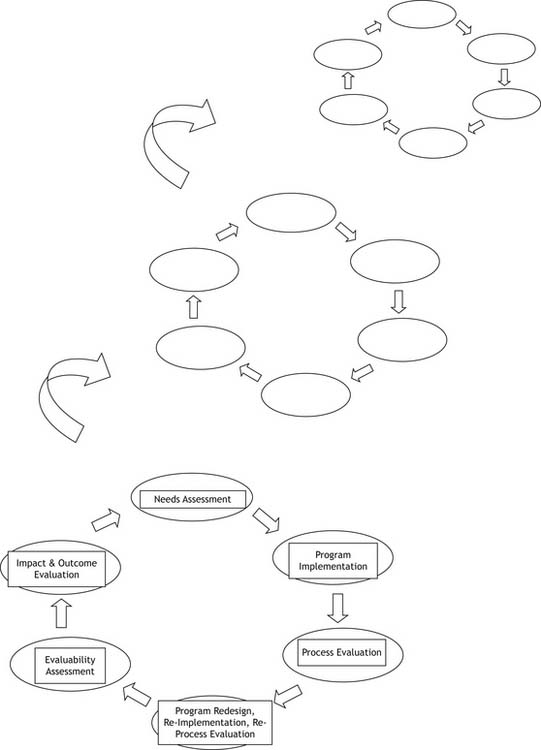

This chapter deals with step 1, identifying a specific issue, step 5, evaluability assessment, and step 6, evaluating the program from the cycle. Designing the program, developing an action plan and implementing the program will be dealt with in other chapters according to the activities the community decides upon. The steps in program-planning and evaluation are best thought of as a continuing cycle (as illustrated in Figure 6.1) rather than as a linear sequence of events. The cyclical process indicates that the process is never ‘finished’; when one round of interventions is complete, one reflects on the evaluation findings and plans relevant new interventions.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS THAT GUIDE PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT AND EVALUATION

Research in Primary Health Care

The inextricable relationship between research and practice means that the additional resources required to carry out research may not be as great as expected. When research is an integral part of practice, it is as much a state of mind and an approach to working as anything else. Certainly there are times, for example, when a major community assessment may be required and this may necessitate an additional commitment of time and resources and the active involvement of people with expertise in community assessment. However, not researching and improving practice may result in wasting the limited resources that are being allocated to health promotion.

Participatory research: the Primary Health Care approach in action

Participatory action research

Participatory action research in community development has been defined as:

Participatory action research is based on a strong set of values relating to social justice and empowerment of oppressed groups, through working to change those things that constrain their lives, including dominating social structures. It is conducted in ways that are ‘democratic, participatory, empowering and life-enhancing’ (Stringer & Genat 2004: 28).

There are several characteristics of participatory action research:

1. The problem originates in the community itself and is defined, analysed and solved by the community.

2. The ultimate goal of research is the radical transformation of social reality and improvement in the lives of the people involved. The primary beneficiaries of the research are the community members themselves.

3. Participatory research involves the full and active participation of the community in the entire research process.

4. Participatory research involves a whole range of powerless groups of people — the exploited, the poor, the oppressed, the marginalised.

5. The process of participatory research can create a greater awareness in people of their own resources and can mobilise them for self-reliant development.

6. Participatory research is a more scientific method, in that community participation in the research process facilitates a more accurate and authentic analysis of social reality.

7. The researcher is a committed participant, facilitator, and learner in the research process, and this leads to militancy, rather than detachment.

Because organisational action research is built on recognition of the inextricable links between research and practice (Carr & Kemmis 1986), it has a great deal to offer health workers. It is ideal as an approach to working with community members, enabling them to reflect on their own experiences, plan how they can act to change their situation, act and then evaluate the impact of the changes in order to then re-plan, re-act and re-evaluate in a continuing cycle of change, development and learning. It can also be used to provide a framework for health workers to continually analyse and develop their own practice. That is, it provides a framework for good reflective practice.

Feminist research

1. There is a recognition that research is not value-free. Therefore, rather than attempting to remain totally distant from and uninvolved with research participants, feminist researchers identify with them sufficiently to see the problem from their perspective as well as their own.

2. The relationship between researcher and research participants is an equal, non-hierarchical and collaborative partnership, not one where researchers are the ‘experts’. This is reflected in the use of the term research ‘participant’, rather than ‘subject’. Without this partnership approach to research, researchers contribute to the oppression of people they are attempting to help.

3. Research is inseparable from the wider actions for improvement of women’s position in society. Therefore, researchers are also engaged in active participation in actions to mediate unequal power relations.

4. The interrelationship between action and research indicates that an inherent part of feminist methodology is built around changes to women’s position in society and the fight for emancipation through participation, reflection and action.

5. The research process must become a process of ‘conscientisation’, or critical consciousness-raising, for both researchers and research participants. That is, through the research process, people are enabled to see the social, political and economic constraints on their lives and therefore recognise the context in which their lives are lived. This process also results in recognition of the experiences individual women share with each other; consequently, the power of the group becomes recognised and can be used for collective action.

Towards a Primary Health Care approach to research

Research is a dynamic cyclical process, inextricably intertwined with action. Its aim is to improve the conditions under which people live.

Research is a dynamic cyclical process, inextricably intertwined with action. Its aim is to improve the conditions under which people live.

The research process is guided by critical self-reflection on the part of the ‘researcher’ and the research participants. The values of researcher and research participants are acknowledged up front and are the subject of critical self-reflection as part of the research process. Conscientisation is a key feature of this process.

The research process is guided by critical self-reflection on the part of the ‘researcher’ and the research participants. The values of researcher and research participants are acknowledged up front and are the subject of critical self-reflection as part of the research process. Conscientisation is a key feature of this process.

The relationship between researcher and research participants is a partnership that itself acts to change the status quo by breaking down the traditionally ‘top-down’ approach of researchers. Thus, all people involved in the research process are best described as research partners.

The relationship between researcher and research participants is a partnership that itself acts to change the status quo by breaking down the traditionally ‘top-down’ approach of researchers. Thus, all people involved in the research process are best described as research partners.

Ethical considerations in program development and evaluation

There are international and national rules governing how research is conducted. It is not proposed that we deal comprehensively with ethical issues here. (See Owen & Rogers 1999 Ch 8 for a comprehensive overview of guidelines for ethical practice in community-based evaluation research.) In Australia, the Australian Health Ethics Committee (http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/health_ethics/ahec/index.htm) advises the National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC) on ethical issues relating to health and the development of guidelines for the conduct of medical research involving humans. Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) oversee research on behalf of this organisation. These committees are found in large organisations such as universities, education departments, health departments and large hospitals. The Centre for Disease Control has excellent resources for ethics principles and standards from various countries (http://www.cdc.gov/eval/resources.htm

The principles of Primary Health Care provide a solid foundation for conducting needs assessments and evaluation within the program-planning cycle. However, research procedures form the basis of these processes and therefore further discussion is needed concerning some of the ethical issues that health workers need to consider, whether they seek HREC approval or not.

Five categories of ethical issues have been identified:

Recognising role conflicts

Why is the research being done?

Why is the research being done?

Who is conducting the research?

Who is conducting the research?

Who will have access to the findings?

Who will have access to the findings?

Using valid methods

When it is clear that the participants can come to no harm and that the potential for conflict is minimised, then it is important to focus on the validity of the project. Research design must fit the needs of those who will utilise the information. Conducting research that is not suitable for the purposes for which it was commissioned is unethical. Experienced data collectors and analysts need to be involved in research. If quantitative methods are to be used, then a standardised test appropriate to the setting will minimise the risk of invalid results (Posavac & Carey 2003). If interviews form part of the process then experienced interviewers are required, to avoid wasting the interviewee’s time and research program funds through meaningless or inadequate interviewing. Interviewing requires tremendous skill.

PLANNING IN PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

The PRECEDE planning model

PRECEDE — an acronym for predisposing, reinforcing and enabling constructs in ecosystem diagnosis and evaluation (http://www.lgreen.net/precede.htm).

PRECEDE — an acronym for predisposing, reinforcing and enabling constructs in ecosystem diagnosis and evaluation (http://www.lgreen.net/precede.htm).

PROCEED — an acronym for policy, regulatory and organisational constructs in educational and environmental development.

PROCEED — an acronym for policy, regulatory and organisational constructs in educational and environmental development.

There are eight phases in the combined PRECEDE–PROCEED model for program development and evaluation. The information gathered is often referred to as primary and secondary data. Phases one to four (PRECEDE) are addressed in this chapter. This model is constantly evolving and so for a detailed discussion on the model refer to Green and Kreuter (2005); to http://www.lgreen.net/precede.htm or to the EVOLVE website where links to useful websites are provided and where you can find articles, chapters and books in which the PRECEDE–PROCEED model has been applied, examined or extended.

The first phase is social assessment, which refers to the needs that are defined by a community in terms of the dimensions of their quality of life. This means asking the community to identify and discuss their needs and aspirations (Green & Kreuter 2005). This phase assists planners to assess the uniqueness of a community. The kinds of social problems a community experiences are a practical and accurate barometer of its quality of life and include such things as discrimination, poverty, isolation, self-esteem or poor nutrition. A range of methods can be used to undertake community assessments, some of which are described in more detail later in this chapter.

Phase three is the educational and ecological assessment. This phase consists of sorting and categorising the factors that seem to have direct impact on the behaviour or the environment. Interventions that are planned within these categories will depend on their relative importance and the resources available. The PRECEDE model groups them according to the educational and organisational strategies likely to be employed in a health promotion program to bring about environmental and behavioural change. Refer back to the iceberg model of disease presented in Chapter 1 and notice how the PRECEDE model can be used to assess needs at all levels in the iceberg.

1. Predisposing factors — a person’s or population’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values and perceptions that facilitate or hinder the capacity for change.

2. Enabling factors — can be viewed as the skills and resources necessary for change. The vehicles or barriers, created mainly by societal forces, can enhance or hinder change. Facilities or community resources may be ample or inadequate; laws may be supportive or restrictive. Enabling factors thus include all the factors that make possible a desired change in behaviour or in the environment.

3. Reinforcing factors — the feedback received from others following adoption of the changed situation may encourage or discourage continuation of the changed situation.

The program is then implemented and evaluated. We will be discussing evaluation later in the chapter; however, listing evaluation last is misleading. Evaluation is an integral and continuous part of working with the entire model from the beginning.

COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT

Community assessments

Community assessment can be defined as a process that results in:

This definition highlights several issues that are central to meaningful community assessment.

1. Community assessment is a process of determining both the needs and the resources of a community. While considerable attention tends to be focused on the needs of communities, and these certainly are important, a focus on needs alone tends to paint a ‘deficit’ picture of communities.

2. Community assessment should be carried out with the active participation of community members. Community members have the right and ability to be meaningfully engaged in determining what their needs and strengths are. Good community assessment is a participatory process.

3. Community assessments are carried out for the specific purpose of achieving change that improves the quality of life of those living as part of that community. A community assessment is not an end in itself, but a guide to action. Unless community assessments are acted on, they are a waste of time and energy (Hawe 1996; McKenzie et al 2005). Community assessments that leave few resources for acting on what is found, or for which there is no real commitment to act on after their completion, are likely to do little to help those for whom the community assessment is purportedly being carried out and are likely to result in significant community frustration (Hawe 1996; Rissel 1991: 30).

Need — what is it?

While comprehensive community assessment examines both the resources and needs of a community, it is true that the notion of needs has a central place in community assessment. This is especially so when there is a focus on social justice and working to achieve equity for those who are disadvantaged. Arguably, any examination of community needs assessment should start, therefore, with an examination of just what need is and a review of some of the issues surrounding the definition of something as a need (Robinson & Elkan 1996). Need has been defined as ‘the condition marked by the lack of something requisite’ (Macquarie Dictionary 2001). This definition highlights the fact that the very concept of need itself is value-based and socially constructed. Whether something is identified as a need will depend on the perspectives and values of those involved. In addition, it is through the way in which issues are defined at a social and political level that individuals, groups and societies come to decide which issues are of concern to them and which things they need. Given the value-laden nature of need, it is important to be clear about which values should be driving the needs-identification process in the Primary Health Care approach.

Felt need

Fourthly, the perspective of a small group of community members may not reflect the perspective of the whole community. Careful consideration needs to be made of whom a group of community informants represent — a section of the community, a small subsection or only themselves (Hawe et al 1990; McKenzie et al 2005; Robinson & Elkan 1996).

Expressed need

Of course, this expressed need has even more limitations on it than felt need, as people can only add their names to waiting lists for services that already exist or are about to come into existence. Indeed, waiting lists are limited to issues of service provision: it is not possible to join a waiting list for a new public policy, for example, although the number of letters written to a politician on a particular issue may be regarded as another form of expressed need.

Comparative need

All of these needs tell us different things. A combination of social, epidemiological, environmental, behavioural and administrative assessments provide us with a comprehensive base from which to plan programs.

In preparing to assess the needs of any individual, group or community, it is vital to know why the particular assessment needs to be done. What needs to be known, and to what end (Robinson & Elkan 1996)? This will help determine how the assessment should be conducted. Adequate resources need to be available. As discussed above, uncovering needs, creating the expectation that something will be done about them, then not acting, is unlikely to develop confidence in those whose time has been wasted. Box 6.1 outlines the principles that underpin a Primary Health Care approach to community assessments and Box 6.2 outlines the steps.

BOX 6.1 Principles of community assessment

1. Community assessment should be an integral part of health promotion work.

2. Community assessment should reflect the social view of health, which is so much a part of health promotion and Primary Health Care.

3. Community assessment should involve both formal and informal assessment of needs and resources or assets.

4. Community assessment should recognise the partnership between people themselves and health workers in determining their needs and resources, planning action and evaluating any outcomes. Part of this process may involve negotiation between community members and health workers.

5. Needs assessment should involve a combination of felt, expressed, normative and comparative need.

BOX 6.2 The steps in community assessment

1. Identify the purpose of the community assessment.

2. Identify available resources.

3. Establish a project team and steering committee.

4. Develop a research plan and time frame.

5. Collect and analyse available information.

6. Complete community research.

(Source: South Australian Community Health Research Unit (SACHRU) 1991 Planning Healthy Communities: a Guide to Doing Community Needs Assessment. SACHRU, Adelaide)

Community needs assessment is a process of determining both the needs and the resources of a community. While considerable attention tends to be focused on the needs of communities, and these certainly are important, a focus on needs alone tends to paint a ‘deficit’ picture of communities (McKenzie et al 2005).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree