Chapter 33 BOWEL ELIMINATION

THE DIGESTIVE TRACT

ANATOMY

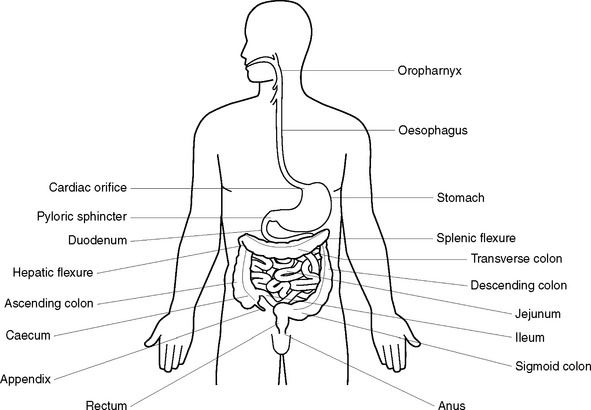

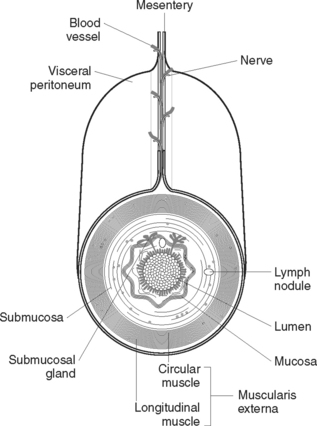

The digestive tract is a muscular tube about 9–10 metres in length, which extends from the mouth to the anus (Figure 33.1). The structure of the alimentary canal is similar for most of its length and consists of an outer covering, middle layers of involuntary muscle and connective tissue, and an inner mucous membrane lining (Figure 33.2).

The outer covering of the alimentary canal consists of fibrous tissue (the serosa) or, in the abdomen, peritoneum. The peritoneum is a double-layer serous membrane that secretes serous fluid to prevent friction between the abdominal organs. The inner layer is called the visceral serous membrane and the outer layer the parietal serous membrane. The two layers of the peritoneum are kept proximate and separated by peritoneal fluid. The peritoneum forms a lining for the abdominal cavity (parietal layer) and a covering for most of the abdominal organs (visceral layer). The mesentery, which is formed by the peritoneum, covers the intestines and attaches them to the posterior abdominal wall. Ligaments are formed by folds of peritoneum to attach some organs to each other or to the abdominal wall. The greater omentum is attached to the lower border of the stomach and hangs down like an apron and loops up to be attached to the transverse colon. The lesser omentum extends from the lower border of the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach.

The mouth

Components of the mouth

The oesophagus

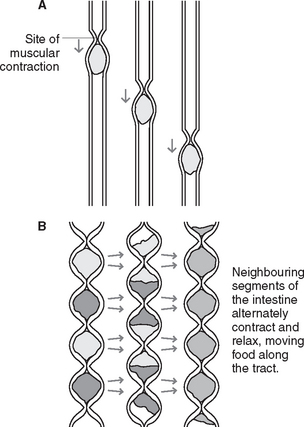

Peristalsis is a wave-like progression of alternate contraction and relaxation of the muscle fibres of the oesophagus or intestines, by which contents are propelled along the alimentary canal. At rest, the opening between the oesophagus and pharynx (oesophageal sphincter) is closed. During swallowing the muscles contract and cause the sphincter to open, thereby allowing the bolus of food to pass down into the oesophagus. A wave of contraction in the circular muscle layer then propels the bolus down to the stomach. The bottom end of the oesophagus acts as a functional sphincter, which is normally in a state of tonic contraction. As the peristaltic wave approaches the sphincter, the muscle relaxes and allows food to enter the stomach. The sphincter then closes again and prevents regurgitation of gastric contents back into the oesophagus.

The stomach

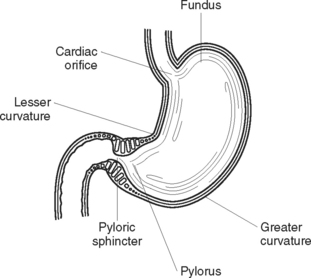

The stomach is a hollow muscular organ that lies primarily in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen, beneath the diaphragm (Figure 33.3). It is commonly described as being ‘J shaped’, but the size and shape of the stomach varies according to its contents. The stomach is divided into four areas: the fundus (the upper portion); the cardia, where the oesophagus joins the stomach; the body, or main part of the stomach; and the pylorus (the narrowed lower portion).

The stomach wall consists of four layers:

Functions of the stomach

The small intestine

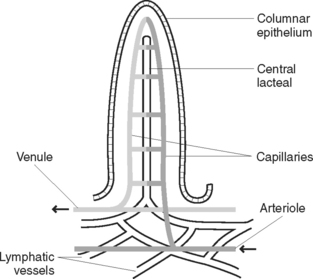

Covering the mucosa are very fine projections called villi (Figure 33.4). Intestinal glands in the mucous membrane secrete an intestinal juice containing enzymes to complete the digestion of food. Solitary and aggregated patches of lymphatic tissue (Peyer’s patches) are also found in the mucosa of the intestinal wall, especially in the lower ileum. An opening in the duodenum (ampulla of Vater) allows for the entry of the common bile duct, carrying bile from the liver, and the pancreatic duct, carrying pancreatic juice. At the junction of the ileum and the caecum of the large intestine is the ileo-caecal valve, which prevents a backward flow of contents from the large to the small intestine.

The large intestine

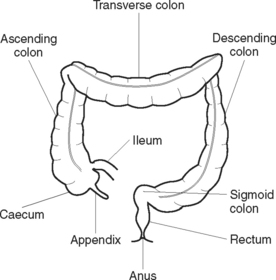

The large intestine is a muscular tube about 1.5 m in length and 6 cm in diameter, and extends from the end of the ileum to the anus (Figure 33.5). Lying in the abdominal and pelvic cavities, the large intestine may be divided into regions that are distinguished by their anatomical structure and position:

Functions of the large intestine

The four functions of the large intestine are:

THE ACCESSORY DIGESTIVE ORGANS

The pancreas

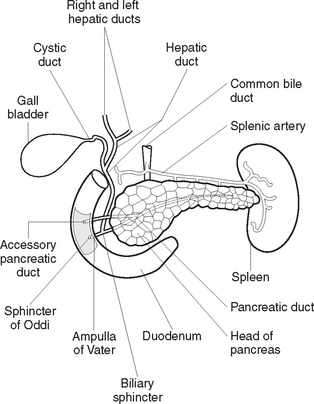

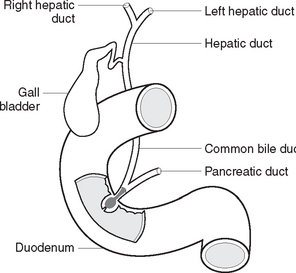

The pancreas is a soft gland, lying across the abdominal cavity behind the stomach. It is divided into a head, which fits into the curve of the duodenum; a central portion, or body; and a tail, which extends out to the spleen. The pancreatic duct runs centrally through the length of the pancreas, while smaller ducts carry the pancreatic juice secreted by the pancreas into the central duct. The pancreatic duct joins the common bile duct from the liver, to enter the duodenum (Figure 33.6).

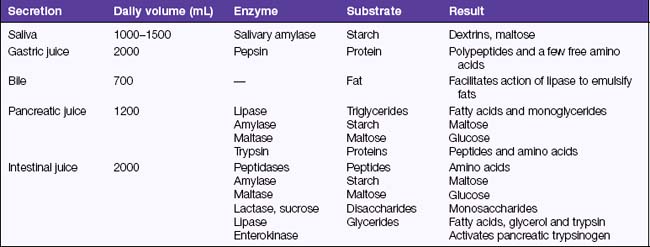

The bulk of the tissue in the pancreas is composed of exocrine cells, which produce pancreatic juice. The pancreas secretes about 1200 mL of pancreatic juice daily. Pancreatic juice is a watery alkaline fluid rich in digestive enzymes. The enzymes and their actions are summarised in Table 33.1. The overall function of pancreatic juice is the digestion of nutrients. Scattered among the exocrine tissue are groups of hormone-secreting cells, the islets of Langerhans. The function of the islets of Langerhans is described in Chapter 41 on endocrine health, as these cells belong to the endocrine system.

The liver

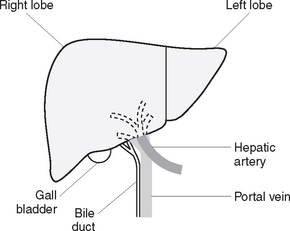

The liver is an organ situated in the upper part of the abdominal cavity, immediately beneath the diaphragm. The greater part of the liver lies in the right upper abdomen but the organ extends across to the left upper abdomen (Figure 33.7). The liver is divided into two parts, a large right lobe and a much smaller left lobe. Like the alimentary canal, the liver is almost entirely covered by a layer of peritoneum. Beneath this is a fibrous capsule, which is continuous with areolar connective tissue situated within the liver. The areolar tissue forms a tree-like structure, which carries branches of the hepatic artery, hepatic portal vein, bile ducts and lymphatic vessels. These vessels enter and leave the liver through the porta hepatis, a short transverse fissure on the inferior surface of the liver.

The hepatic artery carries oxygenated blood to the liver. The portal vein carries deoxygenated blood, rich in nutrients from the small intestine, to the liver. Three hepatic veins carry deoxygenated blood from the liver to the inferior vena cava. The right and left hepatic ducts carry bile, secreted by the liver, to the common hepatic duct. The latter combines with the cystic duct from the gall bladder to form the common bile duct, which drains into the duodenum. The biliary tract, which transports bile from the liver to the duodenum, consists of the left and right hepatic ducts, the common hepatic duct, the cystic duct, the gall bladder and the common bile duct (Figure 33.8).

The gall bladder

Functions of the liver and gall bladder include:

PHYSIOLOGY OF DIGESTION

DIGESTION OF FOOD

Digestion in the mouth

After the food has been formed into a bolus it is passed through the pharynx and down the oesophagus into the stomach by the act of swallowing. Swallowing is a complex reflex regulated by a ‘swallowing centre’ in the medulla oblongata of the brain. Swallowing is initiated when the tongue muscles push the bolus upwards and backwards into the oropharynx. The soft palate is elevated and comes into contact with the posterior wall of the pharynx, thereby closing off the nasopharynx. The larynx is pulled upwards and forwards, and the bolus pushes the epiglottis back over the glottis to prevent food from entering the respiratory tract. The oesophageal sphincter opens and the bolus enters the oesophagus.

Digestion in the stomach

Digestion in the small intestine

ABSORPTION OF DIGESTED FOOD

Most substances, for example, amino acids and monosaccharides, are absorbed through the villi walls by the process of active transport, and enter the capillaries in the villi to be transported in the blood to the liver via the portal vein. The exception is lipids (fats), which are absorbed passively by the process of diffusion. Lipids enter central lacteals in the villi to be transported in the lymph. Lymphatic vessels empty their contents into the thoracic duct, which then drains the lymph into the blood at the subclavian vein. The proximal colon is the main site for the absorption of certain substances from chyme, including mineral salts and water. Vitamins B and K are synthesised by bacteria in the colon and absorbed into the bloodstream.