10 Bones of the limbs

Bones of the upper limb

The bones of the upper limb are:

| |

| |

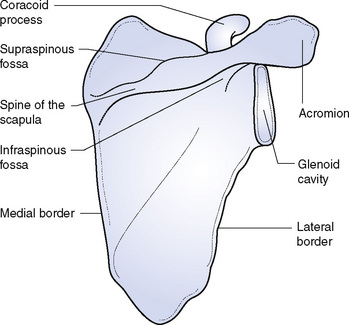

The scapula (Fig. 10.1) is a triangular flat bone; it lies over the ribs at the back of the thorax but does not articulate with them. It is held in place by muscles which attach it to the ribs and vertebral column. This arrangement gives great freedom of movement to the shoulder girdle, making it possible to reach widely both forwards and backwards and to either side of the body. It is not often broken by falls as it is embedded in muscle. It has three borders and three angles; the lowest is spoken of as the angle because it is the sharpest and is easily felt. The front surface is concave to fit over the ribs; the posterior surface is convex and carries a projecting ridge of bone known as the spine of the scapula, which provides attachment for muscles and forms two depressions or fossae, one above and one below it.

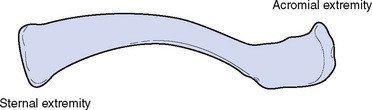

The clavicle (Fig. 10.2) is a long bone, roughly S-shaped. It articulates with the sternum at its inner or sternal extremity and with the scapula at its outer or acromial extremity. The two extremities are easily distinguishable from one another: the inner is roughly like a pyramid in shape, while the outer is flatter and very similar in shape and form to the acromion process of the scapula, with which it articulates. The bone lies close under the skin and is easily felt along its whole course; starting from the sternal extremity, it curves first forwards and then backwards. It keeps the scapula in position and if it is broken the shoulder drops forwards and downwards. It is the only bony link between the bones of the upper limb and the axial skeleton, as the scapula does not articulate with either the ribs or vertebral column. It is a bone that is not found in the skeleton of many four-footed animals as it only becomes necessary to fix the scapula when the limb is moved outwards from the trunk. The bone is easily broken by falls on the shoulder as it is compressed between the sternum and the point of impact; it is, in fact, better that it should break than that there should be an injury at the root of the neck, where there are many important structures, or about the shoulder joint, where injury would be likely to limit subsequent movement.

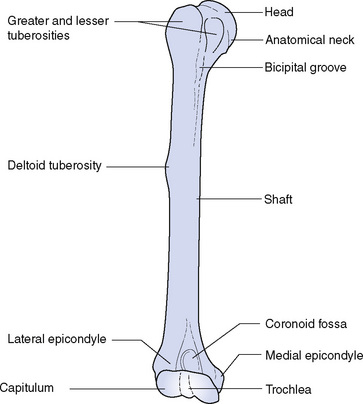

The humerus (Fig. 10.3) is the largest and longest bone of the upper limb. The upper extremity has a hemispherical head, covered with hyaline cartilage, which articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula, forming the shoulder joint. The anatomical neck forms a slight constriction adjoining the head, and the greater and lesser tuberosities lie below the neck and provide attachment for muscles. Between the tuberosities, a deep groove accommodates one of the tendons of the biceps muscle. The shaft of the humerus has many roughened surfaces for the attachment of muscles, the most marked being the deltoid tuberosity on the outer side, which gives insertion to the deltoid muscle. A groove running obliquely round the shaft carries the radial nerve, one of the three main nerves of the upper limb.

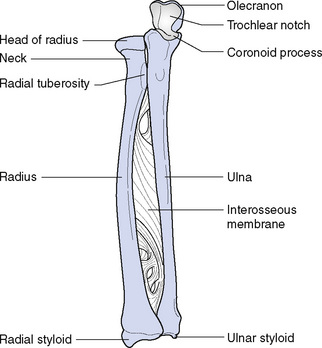

The radius (Fig. 10.4) is the outer bone of the forearm. The upper end is smaller and has a disc-shaped head with a hollowed upper surface to articulate with the capitulum of the humerus. The head also articulates with the ulna. The neck of the radius is the constricted portion below the head, and on the ulnar side there is a projection called the radial tuberosity, which gives insertion to the biceps muscle. The shaft of the bone has a sharp ridge facing the ulna and from it a sheet of fibrous tissue called the interosseous membrane runs to the ulna, connecting the two bones. The lower end of the radius is the wider part and comprises part of the wrist joint; it also has a projection called the styloid process, which can be felt at the base of the thumb.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree