Chapter 5 Biological and environmental determinants

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

identify and discuss the range of physical, biological and environmental determinants that impact on health

identify and discuss the range of physical, biological and environmental determinants that impact on health suggest why it is important to the practice of public health that you understand how determinants contribute to health

suggest why it is important to the practice of public health that you understand how determinants contribute to healthIntroduction

This chapter describes biological and environmental determinants of the health of Australians, providing a background to the development of successful public health activity. You will recall from the Introduction to Section Two that health determinants are the biomedical, genetic, behavioural, socioeconomic and environmental factors that impact on health and wellbeing. These determinants can be influenced by interventions and by resources and systems (AIHW 2006). Many factors combine to affect the health of individuals and communities. People’s circumstances and the environment determine whether the population is healthy or not. Factors such as where people live, the state of their environment, genetics, their education level and income, and their relationships with friends and family are all likely to impact on their health. The determinants of population health reflect the context of people’s lives; however, people are very unlikely to be able to control many of these determinants (WHO 2007).

This chapter and Chapter 6 illustrate how various determinants can relate to and influence other determinants, as well as health and wellbeing. We believe it is particularly important to provide an understanding of determinants and their relationship to health and illness in order to provide a structure in which a broader conceptualisation of health can be placed. Determinants of health do not exist in isolation from one another. More frequently, they work together in a complex system. What is clear to anyone who works in public health is that many factors impact on the health and wellbeing of people. For example, in the next chapter we discuss factors such as living and working conditions, social support, ethnicity and class, income, housing, work stress and the impact of education on the length and quality of people’s lives.

In Chapter 3 you were introduced to National Health Priority Areas including: cancer control, injury prevention and control, cardiovascular health, diabetes mellitus, mental health, asthma, arthritis and musculoskeletal conditions. As you will recall from that chapter, the National Health Priority Areas set the agenda for the Commonwealth, states and territories, local governments and not-for-profit organisations to place attention on those areas considered to be the major foci for action. Many of these health issues are discussed in this chapter and the following chapter.

A complex web of determinants

Determinants are in complex interplay and range from the ‘upstream’ background influences (e.g. culture and wealth), with many health and non-health effects that can be difficult to quantify, to immediate or direct influences with highly specific effects on particular aspects of health. They are often described as part of broad causal ‘pathways’ or ‘chains’ that affect health (Keleher & Murphy 2004).

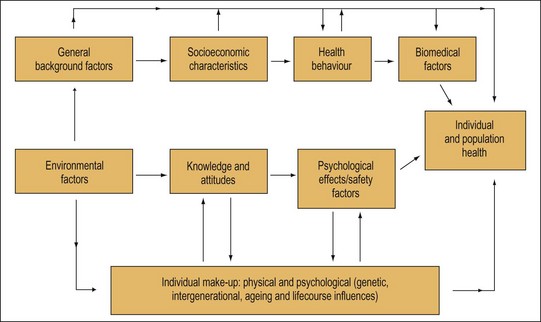

The Public Health Agency of Canada (2007) defines 11 determinants of health (Table 5.1). Examining these issues briefly in tabular form gives you an idea of the range of factors that impact on health. Figure 5.1 collapses these many determinants into a manageable and simple framework for your consideration. Some of these determinants are discussed further in this chapter and the remaining determinants are considered in the following chapter.

TABLE 5.1 Determinants of health

| Determinants of health | Description |

|---|---|

| Income and social status | Much research suggests poor people are less healthy than rich people; income distribution is a key element |

| Social support networks | Support from family, friends and community is linked to health |

| Employment and working conditions | Unemployment and poor health are related; more control over working conditions improves health |

| Education | Low literacy levels are linked to poor health |

| Physical environments | Clean air and water, healthy workplaces, safe houses, communities and roads all contribute to health |

| Genetics | Inherited characteristics play a role in determining how long we live, how healthy we will be and the likelihood of contracting certain illnesses |

| Personal health practices and coping skills | Physical activity, good nutrition, smoking and drinking and coping skills impact on health |

| Healthy child development | Good health in childhood has a positive influence on later life |

| Health services | Access to services that prevent diseases benefits health |

| Gender | Different kinds of diseases and conditions affect women and men differently |

| Culture | Customs and beliefs affect health |

(Source: Public Health Agency of Canada 2007)

Figure 5.1 presents a range of determinants and their pathways. The pathways are not linear and can also occur in reverse. For example, an individual’s health can influence their physical activity levels, employment status and wealth. General background factors and environmental factors can determine the nature of socioeconomic characteristics and both can influence people’s health behaviour, their psychological state and factors relating to their safety. These, in turn, can influence biomedical factors, such as blood pressure and body weight, which may have health effects through various further pathways. At all stages along the path these various factors interact with an individual’s genetic composition. This framework then shows us a simple way of organising and examining the various pathways that may occur in a range of different contexts.

An important use of determinants is to enable us to focus on where best to intervene. Turrell et al. (2006) identify three broad levels of factors affecting health and how interventions might be structured based on these levels, as follows:

Genetics and screening

Genetic determinants are important factors impacting on individual health and they will continue to be important, as nearly every disease has constitutive and/or acquired genetic components. Identifying disease susceptibility genes, as well as identifying acquired somatic mutations underlying a specific disease such as cancer, can provide vital information for a more thorough understanding of many common illnesses. This information can then be used to determine how diseases are diagnosed and how new treatments or particular drug therapies can be identified (Europa 2007).

‘Genes are the units of heredity which control the structure and function of the body by determining the structure of peptide chains that form the building blocks of enzymes and other proteins’ (Harper et al. 1994 p 119). A gene’s role is to ensure that the amino acids are always in the same order. Genes are located at specific points in the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in the cell nucleus and the DNA is arranged into 23 pairs of chromosomes. Of these, 22 are called autosomes while the other pair is the sex chromosomes. One of each pair of chromosomes is derived from each parent. There are several categories of genetic disease depending upon the location and the extent of the genetic abnormality. The categories include single-gene disorders, chromosomal disorders, disorders involving several genes and environmental influences, disorders of cytoplasmic DNA and mutations of somatic cells.

The Human Genome Project commenced in 1990 as a 15-year, large-scale, international project that involved the USA, the UK, France, Canada, Germany, Japan and China. The primary goal was to sequence the entire human genome, with other goals including identifying genes, improvements in technology and data analysis, comparative genomics and the ethical, legal and social implications of such a project. ‘From a public health perspective, there is a danger that the enthusiasm for genomics may deflect attention and resources from the important mission of preventing disease in the population’ (Schneider 2006 p 211). Genomics is the study of how genes act in the body, and how they interact with environmental influences to cause disease. The fundamental question for public health is the extent to which applying this emerging knowledge will divert resources from the mission of public health, which is to prevent disease in the population.

Diabetes is caused by resistance to, or deficient production of, the hormone insulin, which helps glucose move from the blood into the cells. When the body does not produce or use enough insulin, the cells cannot use glucose and the blood glucose level rises. This means that the body will instead start to break down its own fat and muscle for energy. Diabetes may lead to severe problems, including damage to the heart, blood vessels, eyes, nerves and kidneys (Department of Health and Ageing 2006 website). Diabetes is defined as a chronic disease in Australia. In the United States the definition of a chronic disease is different from the Australian definition. There are some websites listed at the end of the chapter that will help you consider different definitions of chronic disease. The last section of the activity asks you how public health might contribute to promotion, prevention and rehabilitation of people with diabetes. Think back to what you have learned about the nature of public health, the determinants that contribute to diabetes and what public health strategies might be put in place as prevention and rehabilitation strategies for diabetes.

Biological and behavioural determinants

Biological determinants

Biology refers to the individual’s genetic make-up, family history and the physical and mental health problems acquired during life. Ageing, diet, physical activity, smoking, stress, alcohol or illicit drug use, injury or violence, or an infectious or toxic agent may result in illness or disability and can produce a ‘new biology’ for the individual (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010; Office of Disease Prevention 2007).

Behavioural determinants

Individual health practices are responses or reactions to internal stimuli and external conditions. Both behaviour and biology can have a reciprocal relationship, with each reacting to the other when a person is exposed to a particular health condition. Examples of the reciprocity of the relationship can be seen in the case of a family history of heart disease (biology), which may motivate an individual to add healthy eating behaviours, maintain an active lifestyle and avoid tobacco smoking (behaviours), thus preventing the development of heart disease (biology). Personal choices and the social and physical environments surrounding individuals can shape behaviours. The social and physical environments also include factors that affect the life of individuals, positively or negatively, many of which may not be under their immediate or direct control (AIHW 2010; Office of Disease Prevention 2007).

Tobacco

Tobacco is clearly responsible for, in part, a worldwide epidemic of coronary heart disease and lung cancer. The work of researchers such as Doll and Hill (1964) clearly linked the smoking patterns of individuals with age and cause of death (Keleher & Murphy 2004). The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Burden of Disease Study (Murray & Lopez 1996) reported that, by 2020, it was expected that tobacco would account for 12.3% of deaths worldwide. Smoking rates have been declining for several decades in Australia. Between 1985 and 2007, the prevalence of smoking declined for both males and females. Despite these trends, tobacco smoking continues to cause more ill health and death than other well-known health determinants such as high blood pressure, overweight/obesity and physical inactivity (AIHW 2010). The impact of passive smoking, particularly on children, has become very important in recent years – increasing the likelihood of a number of illnesses, including chest and ear infections, asthma and sudden infant death syndrome (AIHW 2010).

Alcohol

Alcohol plays an important role in the Australian economy and it also has an important social role. It is a familiar part of traditions and customs in this country and is often used for relaxation, socialisation and celebration. Eighty-three per cent of Australians reported drinking alcohol in 2004. It is a drug that can promote relaxation and feelings of euphoria. It can also lead to intoxication and dependence and a wide range of associated harms (Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy 2006).

Some research suggests that benefits from alcohol consumption only occur at very low levels of drinking or that there is no protective effect from drinking (NHMRC 2009).

Injuries

Injury affects Australians of all ages and is the greatest cause of death in the first half of life. It leaves many with serious disability or long-term conditions. Injury is estimated to account for 6.5% of the burden of disease in 2010 (AIHW 2010). For these reasons, injury prevention and control was declared a NHPA and is the subject of three national prevention plans: the National Injury Prevention and Safety Promotion Plan: 2004–2014 (NPHP 2005a), National Falls Prevention for Older People Plan: 2004 Onwards (NPHP 2004) and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Safety Promotion Strategy (AIHW 2010, NPHP 2005b). Injuries were responsible for almost half of the mortality for people under 45 years of age, and account for a range of physical, cognitive and psychological disabilities that seriously affect the quality of life of injured people and their families. Health costs associated with injury in Australia have been estimated to be $2.6 billion annually (AIHW 2010).

Injury usually means physical harm to a person’s body and the most common types of physical injury are broken bones, cuts, poisoning and burns. Physical injury results from harmful contact between people and objects, substances or other things in their surroundings, for example, being struck by a car, cut by a knife, bitten by a dog or poisoned by inhaled petrol. Some physical injuries are the intended result of acts by people: harm of one person by another (e.g. assault, homicide) or self-harm (AIHW 2010, NPHP 2004).

Over recent years, Australia has achieved some significant gains in preventing a number of different types of injuries where concerted efforts have been made. There have been improvements in road safety over the past 25 years. The reduction in road deaths has occurred despite significant growth in the population, vehicle numbers and kilometres travelled. Initiatives, such as random breath testing, compulsory seat belts, speed blitzes, car design and safety features (e.g. air bags), better roads, ongoing community education regarding road safety and improved life-saving medical procedures and trauma care, have all contributed to the decline in the number of vehicle-related fatalities (AIHW 2010, NPHP 2004).

Mental Health

There is a wide spectrum of mental health disorders with varying levels of severity. Some examples include anxiety, depression, bipolar disorders and schizophrenia. Individuals and families suffer from the effect of mental illness, and its influence is far-reaching for society as a whole. To add to the health issues are a range of social problems commonly associated with mental illness, including poverty, unemployment or reduced productivity, violence and crime (AIHW 2010).

The strategy includes a national mental health policy, a mental health plan and a statement of rights and responsibilities. Since 1992, revisions to the policy and plan have occurred and in 2008 the policy was revised and a revised plan was released in 2009. The vision of the National Mental Health Policy 2008 is for a mental health system that enables recovery; prevents and detects mental illness early; ensures that all Australians with a mental illness can access effective and appropriate treatment and community support to enable them to participate fully in the community (Commonwealth of Australia 2009).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree