Lymphedema results from the accumulation of fluid and other elements (such as protein) in the tissues due to an imbalance between interstitial fluid production and transport (usually low output failure). It may arise from congenital malformation of the lymphatic system or from damage to lymphatic vessels or lymph nodes. The resulting swelling typically involves one or more limbs and possibly the corresponding quadrant of the trunk. Swelling also may affect other areas, such as the head, neck, breast, or genitalia. In patients with chronic lymphedema, large amounts of subcutaneous adipose tissue may form.

Although not completely understood, this adipocyte proliferation may explain why conservative treatment may not completely reduce the swelling and return the affected area to its usual dimensions. When lymphedema is inadequately treated, the stagnant, protein-rich fluid not only causes tissue channels to increase in size and number, but also reduces oxygen availability, disrupts wound healing, and fosters bacterial growth and the risk of lymphangitis.

Lymphedema may produce significant physical and psychological morbidity. Increased limb size can interfere with mobility and affect body image. Pain and discomfort are common, and increased susceptibility to acute cellulitis and erysipelas can result in frequent hospitalization and long-term dependence on antibiotics.

At birth, the risk of lymphedema is about 1 in 6,000. The overall prevalence has been estimated at 0.13% to 2%. In developed countries, the main cause of lymphedema is widely assumed to be cancer treatment. Indeed, 12% to 60% of cases have been reported in breast cancer patients and 28% to 47% in patients treated for gynecologic cancer. However, it appears that about one-quarter to one-half of affected patients have other forms of lymphedema, such as primary lymphedema and lymphedema associated with poor venous function, trauma, limb dependency, or cardiac disease.

This chronic condition is as yet incurable and, if ignored, can progress and become difficult to manage. Indeed, many people receive inadequate treatment, are unaware that treatment is available, or do not know where to seek help. However, lymphedema may be greatly alleviated by appropriate management. Appropriate specialized training is required before undertaking much of what this chapter presents.

RISK FACTORS FOR LYMPHEDEMA

Although the true risk factor profile for lymphedema isn’t known, many factors may predispose a person to developing lymphedema or predict the progression, severity, and outcome of the condition. (See

Risk factors for lymphedema.) Further epidemiology is required to completely identify these factors, and research is needed to establish how risk factors themselves can be modified to reduce the likelihood or severity of consequent lymphedema. Effective identification of patients at risk for lymphedema relies on awareness of causes, risk factors, preventive strategies, and self-monitoring.

Patients, caregivers, and health care professionals should be aware that there may be a considerable delay of several years from a causative event to the appearance of lymphedema.

Patients at risk of developing lymphedema and their partners and caregivers need to know what lymphedema is, why the patient is at risk, how to maintain good health, how to minimize the risk of developing lymphedema, early signs and symptoms, and whom to contact if swelling develops. A number of organizations disseminate information helpful in meeting these goals.

Steps to help reduce the risk of lymphedema include:

taking good care of skin and nails

maintaining an optimal body weight

eating a balanced diet

avoiding injury to at-risk areas

avoiding tight underwear, clothing, watches, and jewelry

avoiding exposure to extreme cold or heat

using high-factor sunscreen and insect repellent

using mosquito nets in areas where lymphatic filariasis is endemic

wearing prophylactic compression garments, if prescribed

getting exercise, movement, and limb elevation

wearing comfortable, supportive shoes.

ASSESSMENT

Effective assessment of a patient at risk of or with possible lymphedema should be comprehensive, structured, and ongoing. Here, assessment has been divided into medical assessment and lymphedema assessment, but the two may run in parallel within the same health care setting.

Medical assessment

The medical assessment is used to diagnose lymphedema and to identify or exclude other causes of swelling. (See

Differential diagnosis of lymphedema above.) If the patient presents to a primary care setting, the general practitioner may choose to conduct some initial screening investigations to exclude other causes of swelling before referring the patient for confirmation of the lymphedema diagnosis.

If the patient presents to secondary or tertiary care, assessment may be by a medical specialist. Most cases of lymphedema are diagnosed on the basis of the medical history and physical examination. The choice of investigations used to elucidate the cause of the swelling will depend on the history, presentation, and examination of the patient. They may include a complete blood count, urea and electrolytes, thyroid function tests, liver function tests, plasma total protein and albumin, fasting glucose, C-reactive protein, and others.

Specialist investigations may include:

ultrasound to assess for skin thickening and tissue fibrosis

color Doppler ultrasound to exclude deep vein thrombosis and evaluate venous abnormalities

lymphoscintigraphy to identify lymphatic insufficiency when the cause of swelling is unclear and to differentiate lipedema and lymphedema

micro-lymphangiography using fluorescein-labeled human albumin to assess dermal lymph capillaries

indirect lymphography using water-soluble contrast media to differentiate lipedema and lymphedema

CT/MRI scan to detect thickening of the skin, the honeycomb pattern characteristic of lymphedema, or a tumor that could be causing lymphatic obstruction

bioimpedance to detect edema and monitor the outcome of treatment

filarial antigen card test to detect infection with Wuchereria bancrofti in a person who has visited or is living in an area where lymphatic filariasis is endemic.

Primary lymphedema is usually diagnosed after exclusion of secondary lymphedema. Genetic screening and counseling may be required if there is a suspected familial link. Three gene mutations have been linked with primary lymphedema:

LYMPHEDEMA ASSESSMENT

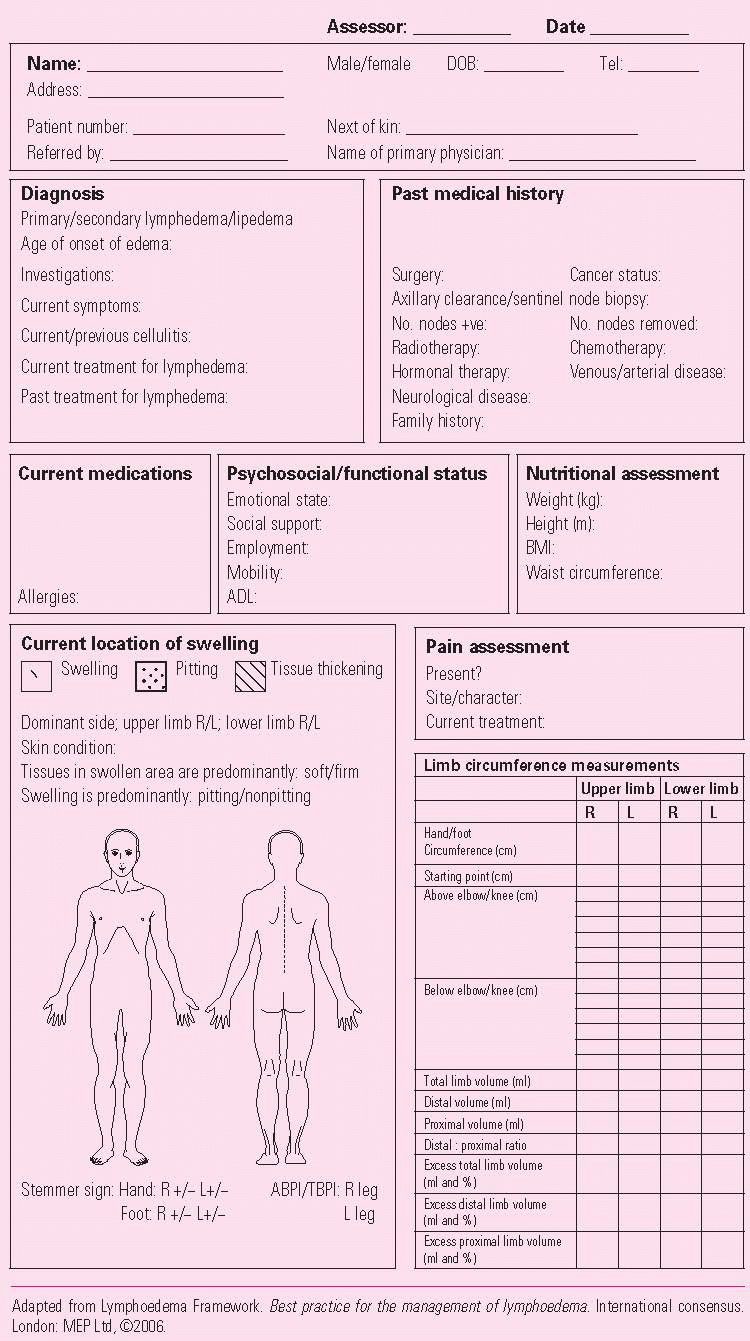

Assessment should be performed at the time of diagnosis and periodically throughout treatment. Findings should be recorded systematically and form the baseline from which management is planned and progress monitored. (See

Lymphedema assessment form, page 88.) Lymphedema assessment usually is carried out by a practitioner with specialist training.

Lymphedema staging

Several staging systems for lymphedema have been devised, including the International Society of Lymphology system. None has achieved international agreement, and each has its limitations.

Classification of severity

One method of establishing the severity of unilateral limb lymphedema is based on the difference in the limb volume between the affected and unaffected limbs. There is currently no formal system for classifying the severity of bilateral limb swelling or lymphedema of the head and neck, genitalia, or trunk. The severity of lymphedema can also be based on the physical and psychosocial impact of the condition. Factors to consider include:

tissue swelling—mild, moderate, or severe; pitting or nonpitting

skin condition—thickened, warty, bumpy, blistered, lymphorrheic, broken or ulcerated

subcutaneous tissue changes—fatty/rubbery, nonpitting or hard

shape change—normal or distorted

frequency of cellulitis or erysipelas

associated complications of internal organs (such as pleural fluid, chylous ascites)

movement and function—impairment of limb or general function

psychosocial morbidity.

A more detailed and comprehensive classification applicable to primary and secondary lymphedema remains to be formulated.

Assessment of swelling

The duration, location, and extent of swelling and pitting should be recorded, along with the location of any lymphadenopathy, the quality of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, and the degree of shape distortion. Limb circumference and volume should be measured.

Limb volume measurement

Limb volume measurement is one of the methods used to determine the severity of lymphedema, the appropriate management, and the effectiveness of treatment. Typically, limb volume is measured on diagnosis, after 2 weeks of intensive therapy with multi-layer inelastic lymphedema bandaging (MLLB), and at follow-up assessment. In unilateral limb swelling, both the affected and unaffected limbs are measured. The difference in limb volume is expressed in milliliters (mL) or as a percentage. In bilateral limb edema, the volume of both limbs is measured and used to track treatment progress.

There is no effective method for measuring edema of the head, neck, breast, trunk, or genitalia. Digital photography is recommended as a way to record and monitor facial and genital lymphedema.

Edema is considered present if the volume of the swollen limb is more than 10% greater than that of the unaffected limb. The dominant limb should be noted because, even in unaffected patients, the dominant limb may have a circumference up to 2 cm greater and a volume as much as 9% higher than the nondominant limb. Several methods are available for estimating volume.

Water displacement method

Also known as water plethysmography, this method is the gold standard for calculating limb volume and is the only reliable method available for measuring edematous hands and feet. It uses the principle that an object will displace its own volume of water.

Circumferential limb measurement

Calculation of volume from circumferential measurements is the most widely used method. It is easily accessible and its reliability can be improved by following a standard protocol.

Perometry

Perometry uses infrared light beams to measure the outline of the limb. From these measurements, limb volume (but not hand or foot volume) can be calculated quickly and accurately.

Bioimpedance

Bioimpedance measures tissue resistance to an electrical current to determine extracellular fluid volume. The technique is not yet established in routine practice. However, it may prove useful in demonstrating early lymphedema, identifying lipedema, and in monitoring the outcome of treatment.

Limitations of excess limb volume

Calculation of excess limb volume is of limited use in bilateral lymphedema. In such cases, measurements can be used to track sequential changes in limb circumference to indicate treatment progress. In patients with extensive hyperkeratosis, elephantiasis, or tissue thickening, some of the excess volume will be from factors other than fluid accumulation.

Assessment of skin condition

The general condition of the patient’s skin and that of the affected area should be assessed for:

dryness

pigmentation

fragility

redness, pallor, cyanosis

warmth, coolness

dermatitis

cellulitis, erysipelas

fungal infection

hyperkeratosis

lymphangiectasia

lymphorrhea

papillomatosis

scars, wounds, ulcers

lipodermatosclerosis

orange peel skin (peau d’orange)

deepened skin folds

Examples of some skin changes in lymphedema can be found in the source document for this chapter, along with indications for referring patients to dermatology or other specialist services.