Benner’s Philosophy in Nursing Practice

Karen A. Brykczynski

A caring, involved stance is the prerequisite for expert, creative problem solving. This is because the most difficult problems to solve require perceptual ability as well as conceptual reasoning, and perception requires engagement and attentiveness.

History and Background

More than 30 years ago, Benner began what she describes as an articulation project of the knowledge embedded in nursing practice (Benner, 1999). Her initial thrust toward further understanding of the theory/practice gap in nursing (Benner, 1974; Benner & Benner, 1979) became transformed while conducting the Achieving Methods of Intra-professional Consensus, Assessment and Evaluation (AMICAE) project, which provided the data for the widely acclaimed book From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice, abbreviated FNE in this chapter (Benner, 1984). Profound exemplars of nursing practices were uncovered from observations and interviews with clinical nurses during this project that demonstrated that clinical nursing practice was more complex than theories of nursing could describe, explain, or predict. This constituted a paradigm shift in nursing by demonstrating that knowledge can be developed in practice, not just applied, and signifying that practice is a way of knowing in its own right.

Two direct outcomes of the AMICAE research project were (1) validation and interpretation of the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition for nurses and (2) description of the domains and competencies of nursing practice. Benner’s ongoing research studies have continued the development of these two components that have been applied extensively in clinical practice development models (CPDMs) for nursing staff in hospitals around the world (Alberti, 1991; Balasco & Black, 1988; Brykczynski, 1998; Dolan, 1984; Gaston, 1989; Gordon, 1986; Hamric, Whitworth, & Greenfield, 1993; Huntsman, Lederer, & Peterman, 1984; Nuccio, Lingen, Burke, et al., 1996; Silver, 1986). These findings have also been used for preceptorship programs (Neverveld, 1990), symposia on nursing excellence (Ullery, 1984), and competency validation in maternal and child community health nursing (Patterson, Leff, Luce, et al., 2004).

The books FNE (Benner, 1984), Expertise in Clinical Nursing Practice (Benner, Tanner, & Chesla, 1996, 2009), and Clinical Wisdom and Interventions in Critical Care (Benner, Hooper-Kyriakidis, & Stannard, 1999, 2011) report studies of skill development in nursing and research-based interpretations of the nature of clinical nursing knowledge. The ongoing development of interpretive phenomenology as a narrative qualitative research method is described and illustrated in each of Benner’s knowledge development publications. The growing body of research that this work has generated is highlighted in the books Interpretive Phenomenology: Embodiment, Caring, and Ethics in Health and Illness (Benner, 1994b) and Interpretive Phenomenology in Health Care Research (Chan, Brykczynski, Malone, et al., 2010). Interpretive phenomenology is both a philosophy and a qualitative research methodology. In these books, Benner and colleagues delineate the historical background, philosophical foundations, and methodological processes of interpretive phenomenological research and examine caring practices and aspects of the moral dimensions of caring for and living with both health and illness.

Benner’s thesis (1984) that caring is central to human expertise, to curing, and to healing was extended in The Primacy of Caring: Stress and Coping in Health and Illness (Benner & Wrubel, 1989). The meaning of caring in this work is that persons, events, projects, and things matter to people. This work examines the relationships between caring, stress and coping, and health. It claims that caring is primary for the following reasons (Benner & Wrubel, 1989):

This book articulates the nursing perspective of approaching persons in their lived experiences of stress and coping with health and illness. It is based on “the notion of the good inherent in the practice and the knowledge embedded in the expert practice of nursing” (Benner & Wrubel, 1989, p. xi). The primacy of caring has been used as a framework for nursing curricula in several schools of nursing including the University of Toronto in Ontario and McMurray College in Illinois (P. Benner, personal communication, January 12, 2000).

Benner’s work is research based and derived from actual practice situations. Darbyshire (1994) stated that her “work is among the most sustained, thoughtful, deliberative, challenging, empowering, influential, empirical [in true sense of being based on data) and research-based bodies of nursing scholarship that has been produced in the last 20 years” (p. 760). Benner’s work has been developed and applied in general staff nursing, critical care nursing, community health nursing, advanced practice nursing, and nursing education.

Benner’s research offers a radically different perspective from the cognitive rationalist quantitative paradigm prevalent during the 1970s and 1980s (Chinn, 1985; Webster, Jacox, & Baldwin, 1981). Her research constitutes an interpretive turn—a move away from epistemological, linear, analytical, and quantitative methods toward a new direction of ontological, hermeneutic, holistic, and qualitative approaches. Benner (1992) has stated that “the platonic quest to get to the general so that we can get beyond the vagaries of experience was a misguided turn….We can redeem the turn if we subject our theories to our unedited, concrete, moral experience and acknowledge that skillful ethical comportment calls us not to be beyond experience but tempered and taught by it” (p. 19).

Overview of Benner’s Philosophy

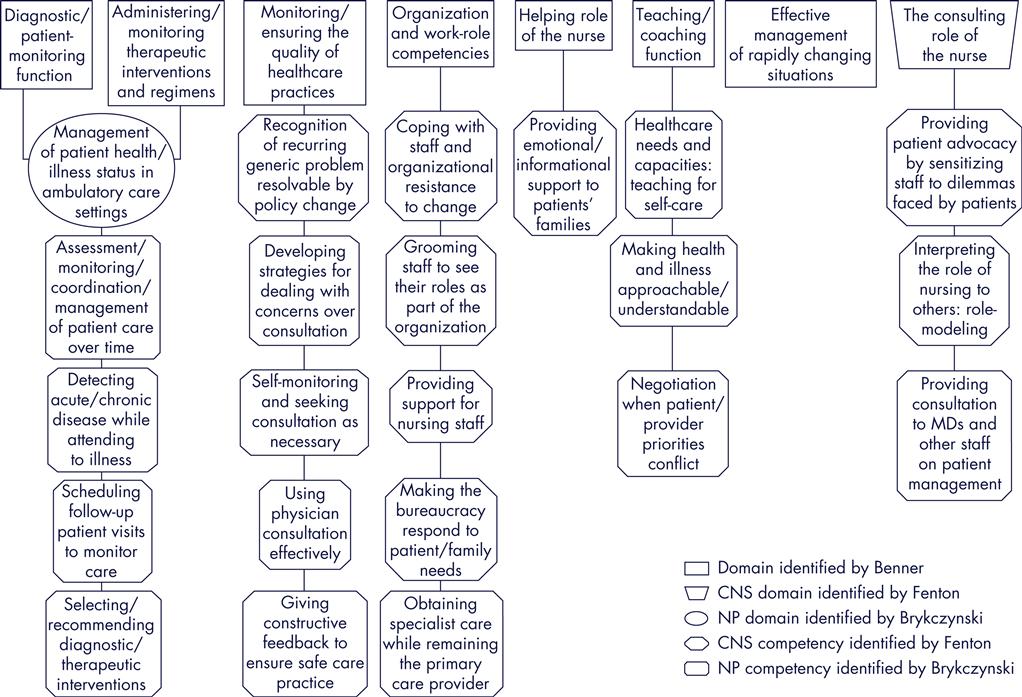

Nursing is a caring practice guided by the moral art and ethics of care and responsibility that unfolds in relationships between nurses and patients (Benner & Wrubel, 1989). The original domains and competencies of nursing practice (Benner, 1984) were identified and described inductively from clinical situation interviews and observations of novice and expert staff nurses in actual practice. This interpretive phenomenological study used a situational approach to the study of the knowledge and meanings embedded in the everyday practice of nurses. “The strength of this method lies in identifying competencies from actual practice situations rather than having experts generate competencies from models or hypothetical situations” (Benner, 1984, p. 44). A holistic perspective such as this provides details of the situational contexts that guide interpretation. Thirty-one interpretively defined competencies were identified and described from the narrative data. These competencies were grouped according to similarities of function, intent, and meaning to form seven domains of nursing practice (Box 7-1).

The helping role domain includes competencies related to establishing a healing relationship, providing comfort measures, and inviting active patient participation and control in care. Timing, readying patients for learning, motivating change, assisting with lifestyle alterations, and negotiating agreement ongoals are competencies in the teaching-coaching function domain. The diagnostic and patient-monitoring function domain refers to competencies in ongoing assessment and anticipation of outcomes. Competencies in the effective management of rapidly changing situations domain include the ability to contingently match demands with resources and to assess and manage care during crisis situations. The domain administering and monitoring therapeutic interventions and regimens incorporates competencies related to preventing complications during drug therapy, wound management, and hospitalization. Monitoring and ensuring the quality of health care practices domain includes competencies concerned with maintenance of safety, continuous quality improvement, collaboration and consultation with physicians, self-evaluation, and management of technology. The organizational and work-role competencies domain refers to competencies in priority setting, team building, coordinating, and providing for continuity of care.

The domains and competencies of nursing practice are nonlinear, with no precise beginning or endpoint. Instead, the nurse enters the hermeneutic circle of caring for the patient by way of whichever competency is needed at the time. One competency in one domain may be more prominent at a particular point in time, but all seven domains and numerous competencies (some not yet identified) will perhaps overlap and come into play at various times in the transitional (ongoing) process of caring for a patient.

The domains and competencies of nursing practice (Benner, 1984) were initially presented as an open-ended interpretive framework for enhancing understanding of the knowledge embedded in nursing practice. The expectation was that they be interpreted in the context of the situations from which they arise along with articulation of ideas of the good or ends of nursing practice. Narrative text must accompany the identification and description of domains and competencies. They are not mutually exclusive, jointly exhaustive categories that can be abstracted from their narrative sources. Because of the socially embedded, relational, and dialogical nature of clinical knowledge, the domains and competencies need to be adapted for each institution. This is achieved through study of clinical practice at each specific locale by systematically collecting 50 to 100 clinical narratives that are then interpreted to identify strengths, challenges, or silences in that practice community. A CPDM can then be designed specifically for the particular setting (Benner & Benner, 1999).

Benner’s work focuses on developing understanding of perceptual acuity, clinical judgment, skilled know-how, ethical comportment, and ongoing experiential learning. Benner’s proposal (1994b) that narrative data be interpreted as text rather than being coded with formal criteria is useful for understanding her work, specifically with regard to expertise, practical knowledge, and intuition. When these terms are considered as formal, explicit criteria (Cash, 1995; Edwards, 2001; English, 1993; Gobet & Chassy, 2008), erroneous interpretations of conservatism, traditionalism, or mysticism may arise. Therefore, each term is discussed in detail in the following sections.

The Dreyfus (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986) model of skill acquisition maintains that expert practice is holistic and situational. Qualitative distinctions betweenthe levels of competence, from the novice to expert skill acquisition model (Benner, et al., 1996), reflect “the situational and relational nature of common-sense understanding and developing expert practice” (Darbyshire, 1994, p. 757). According to this model, which Benner (1984) validated for nursing, expert practice develops over time through committed, involved transactions with persons in situations.

Clinical nursing expertise is embodied—that is, the body takes over the skill. Embodied expertise means that as human beings, we know things with our feelings and bodily senses (sight, sound, touch, smell, intuition), rather than just our rational minds. According to Brykczynski (1998):

To say that expertise is embodied is to say that, through experience, skilled performance is transformed from the halting, stepwise performance of the beginner—whose whole being is focused on and absorbed in the skilled practice at hand—to the smooth, intuitive performance of the expert. The expert performs so deftly and effortlessly that the rational mind, feelings, and perceptions are available to notice the patient and others in the situation and to perceive salient aspects of the situational context (p. 352).

Because expertise in this model is situational rather than defined as a trait or talent, one is not expert in all situations. When a novel situation arises or the usually expert nurse incorrectly grasps a situation, his or her performance in that particular situation relates more to competent or proficient levels. This experience then becomes part of the nurse’s repertoire of background experiences. In future encounters this nurse will approach a similar situation more expertly. This variable nature of expertise is very troublesome for those seeking abstract, objective, mutually exclusive, jointly exhaustive categories. However, it is quite compatible with the holistic, interpretive phenomenological approach. Experts functioning according to this perspective maintain a flexible and proactive stance with regard to possibly forming an incorrect grasp of the particular situation. For example, the intensive care unit (ICU) nurse described in FNE (Benner, 1984) who negotiated for more time for a patient to relax and stop resisting ventilator assistance before administration of additional sedation based her actions on the premise of a concern that she might be wrong. This model of expertise is open to possibilities in the particular situation, which fosters innovative interventions that maximize patient, staff, and other resources and supports to achieve an optimal outcome.

Next, an understanding of distinctions between practical and theoretical knowledge is essential for grasping this perspective (Kuhn, 1970; Polanyi, 1958). Embodied knowledge is the kind of global integration of knowledge that develops when theoretical concepts and practical know-how are refined through experience in actual situations (Benner, 1984). The more tacit knowledge of experienced clinicians is uniquely human. It is the kind of knowledge that computers do not have (Dreyfus, 1992). It requires a living person, actively involved in a situation with the complexity of background and context. The following distinction between human and computer capabilities clarifies aspects of the theory-practice gap so widely discussed in practice disciplines:

All of knowledge is not necessarily explicit. We have embodied ways of knowing that show up in our skills, our perceptions, our sensory knowledge, our ways of organizing the perceptual field. These bodily perceptual skills, instead of being primitive and lower on the hierarchy, are essential to expert human problem-solving which relies on recognition of the whole (Benner, 1985b, p. 2).

Theoretical knowledge may be acquired as an abstraction through reading, observing, or discussing, whereas the development of practical knowledge requires experience in an actual situation because it is contextual and transactional. Clinical nursing requires both types of knowledge. Table 7-1 provides definitions and examples of aspects of practical knowledge based on Benner (1984).

TABLE 7-1

Aspects of Practical Knowledge

| Aspect | Definition | Examples |

| Qualitative distinctions | Perceptual, recognitional clinical judgment that refers to accurate detection of subtle alterations that cannot be quantified and that are often context dependent | Discrete alterations in skin color Significance of changes in mood Different manifestations of anxiety |

| Maxims | Cryptic statements that guide action and require deep situational understanding to make sense | When you hear hoofbeats in Kansas, think horses, not zebras. Follow the body’s lead. |

| Assumptions, expectations, and sets | Knowledge from past experience that helps orient and provide a frame of reference for anticipatory guidance along the typical trajectory Assumptions are beliefs that something is true; expectations are outcomes that can be reasonably anticipated following a certain scenario; sets are inclinations or tendencies to respond to anticipated situations | Assumptions include the ability to maintain and communicate hope in situations based on possibilities learned from previous similar situations. It is expected that an obese person with essential hypertension who loses weight and engages in aerobic exercise 3 times a week will experience a decrease in blood pressure. A set can be illustrated by thinking about the difference in the way a nurse would approach a woman in labor for whom everything seemed to be going normally and the way a nurse would approach the woman if there was a known fetal demise. |

| Common meanings | Shared, taken for granted, background knowledge of a cultural group that is transmitted in implicit ways | It is often better to know even bad news than not to know. The need to advocate for the vulnerable and voiceless |

| Paradigm cases | Clinical experiences that stand out in one’s memory as having made a significant impact on the nurse’s future practice and profoundly alter perceptions and future understanding | The first patient a nurse worked with who stops smoking The first patient with a breast lump who a nurse refers for evaluation |

| Exemplars | Robust clinical examples that convey more than one intent, meaning, or outcome and can be readily translated to other clinical situations that may be quite different An exemplar might constitute a paradigm case for a nurse depending on its impact on personal knowledge and future practice | Helping a patient/family to experience a peaceful death Teaching/coaching a patient/family to live with a chronic illness |

| Unplanned practices | Knowledge that develops as the practice of nursing expands into new areas | Experience gained with available alternative therapies and patient responses to them |

Developed from Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley.

The examples of aspects of practical knowledge described in Table 7-1 are self-explanatory. However, maxims require explanation. The maxim “When you hear hoofbeats in Kansas, think horses, not zebras” reminds clinicians that for most common conditions time-consuming, extensive searches for rare conditions are usually not warranted. The maxim “Follow the body’s lead” relates to the perceptual acuity developed by nurses to intuitively sense the meaning of a patient’s bodily responses. It appears, for example, in situations in which patients are being assessed for readiness to be weaned from ventilator assistance and when nurses evaluate comfortable positions preferred by a particular infant.

In the interpretive phenomenological perspective, the body is indispensable for intelligent behavior rather than interfering with thinking and reasoning. According to Dreyfus (1992), the following three areas underlie all intelligent behavior:

Finally, intuition, rather than mystical, is defined as immediate situation recognition (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986). This definition is based on Merleau-Ponty’s (1962) ideas that “the body allows for attunement, fuzzy recognition of problems, and for moving in skillful, agentic, embodied ways” (Benner, 1995, p. 31). Intuition functions on a background understanding of prior similar and dissimilar situations and depends on the performer’s capacity to be confident in and trust his or her perceptual awareness. This ability is similar to the ability to recognize family resemblances in faces of relatives whose objective features may be quite different. Benner (1996) argues that “[c]linical reasoning is necessarily reasoning in transition, and the intuitive powers of understanding and recognition only set up the condition of possibility for confirmatory testing or a rapid response to a rapidly changing clinical situation” (p. 673).

Interfacing with Practice

Practice and theory are seen as interrelated and interdependent. An ongoing dialogue between practice and theory creates new possibilities (Benner & Wrubel, 1989). In Benner’s work, practice is viewed as a way of knowing in its own right(Benner, 1999). As noted earlier, Benner’s approach to articulating nursing practice is inductive, developmental, and interpretive. She locates it in “the feminist tradition of consciousness raising that seeks to name silences and to bring into public discourse poorly articulated areas of knowledge, skill, and self-interpretations in clinical nursing practice” (Benner, 1996, p. 670).

Articulation is defined as “describing, illustrating, and giving language to taken-for-granted areas of practical wisdom, skilled know-how, and notions of good practice” (Benner, Hooper-Kyriakidis, & Stannard, 1999, p. 5). Since the publication of FNE in 1984, which involved staff nurses from various clinical areas, Benner and colleagues have focused on articulating skill acquisition processes and competencies of nurses in acute and critical care areas (Benner, et al., 1996, 2009; Benner, et al., 1999, 2011). Domains and competencies have also been useful for articulation of knowledge embedded in advanced nursing practice (Brykczynski, 1999; Fenton, 1985; Fenton & Brykczynski, 1993; Lindeke, Canedy, & Kay, 1997; Martin, 1996).

Selected studies illustrate applications of Benner’s work and continued articulation of the competencies of advanced nursing practice. Fenton’s (1985) study indicated that the original domains were present in the practice of clinical nurse specialists (CNSs). She identified additional competencies for three of Benner’s original domains and described one additional domain, the consulting role of the nurse (Figure 7-1). Fenton described the competency making the bureaucracy respond in her study of CNSs. This involved knowing how and when to work around bureaucratic roadblocks in the system so patients and families could receive needed care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree