Chapter 33 Bartonella infections in HIV-infected individuals

Historical Perspective

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA), a unique vascular proliferative lesion, was first described by Stoler and colleagues in 1983 [1] in an HIV-infected patient with multiple subcutaneous nodules. Numerous bacilli were observed by Warthin–Starry staining of the biopsied nodules, and the subcutaneous masses resolved during erythromycin therapy. Subsequently, the BA bacilli visualized using the Warthin–Starry silver stain were noted to have an appearance similar to that of the cat-scratch disease (CSD) bacillus [2, 3]. The BA bacillus remained refractory to isolation attempts for many years, impeding identification efforts. Studies of bacterial DNA extracted from BA lesions subsequently identified the bacillus as closely related to Bartonella (Rochalimaea) quintana [4], and after isolation of the bacillus from the blood of two HIV-infected patients without BA [5], the organism was further characterized and named B. henselae in 1992 [6, 7]. The BA bacillus was directly cultivated from cutaneous BA lesions for the first time in 1992, which led to the identification of two species of the genus Bartonella as causative agents of BA: B. henselae and B. quintana [8].

The Bartonella genus has expanded from a single species in 1993 to 29 officially recognized species (http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/b/bartonella.html) [9, 10], and at least six unofficial Bartonella species. Of these, eight Bartonella species have been isolated from humans: B. henselae, B. quintana, B. elizabethae, B. bacilliformis, B. rochalimae, B. washoensis, B. tamiae, and B. vinsonii subsp. arupensis. Although the Bartonella species causing BA has been identified in more than 60 AIDS patients, only two species have been found to cause BA or bacillary peliosis hepatis [8, 11]. Interestingly, the two different species differ in their predilection to form a specific type of lesion. B. henselae, but never B. quintana, has been associated with peliosis of the liver or spleen, or both [11]. B. henselae also is associated with lymphadenopathy, and B. quintana with subcutaneous nodules in late-stage HIV infection [11].

Clinical Presentation of Bartonella Infections

In patients with severe immunosuppression due to HIV infection, organ transplantation or chemotherapy, infection with B. henselae or B. quintana can produce focal BA lesions composed of proliferating endothelial cells [12, 13]. BA occurs as a late manifestation of HIV infection; in a study of 42 patients with BA, the median CD4 count was 21 cells/mm3 [14]. These vascular proliferative lesions can form in many different organs, including skin, bone, brain parenchyma, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and the gastrointestinal and respiratory tract. A histopathologically different vascular proliferative response to Bartonella infection, known as bacillary peliosis hepatis (BP), is seen in the liver and spleen [15]. One notable aspect of focal Bartonella infection, especially cutaneous BA, is the chronic, indolent nature of the disease: lesions can be present for as long as one year before a diagnosis is made [14, 16].

HIV-infected individuals also can develop manifestations of Bartonella infection other than vascular proliferation. Bacteremia with [17] or without [5, 18] endocarditis has been reported in HIV-infected individuals, in the absence of focal BA or BP involvement. Patients with higher CD4 counts can develop focal necrotizing infections due to B. henselae in lymph nodes, liver or spleen that have an appearance similar to that of CSD in immunocompetent individuals. Rarely, HIV-infected individuals with CD4 counts < 50 cells/mm3 can develop this necrotizing lymphadenitis without vascular proliferation [19].

A case-control study comparing clinical findings of 42 patients with BA and/or BP compared with 84 control patients found that cases were significantly more likely than controls to have fever, abdominal pain, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, a low CD4 count, anemia and/or an elevated serum alkaline phosphatase [14]. With the exception of cutaneous lesions, many of the clinical findings are not specific, and the major obstacle to diagnosis of Bartonella infection in the presence of concomitant HIV infection is recognition of the disease by the physician. BP and BA can be indistinguishable from a number of other infectious or malignant conditions, and the diagnosis can usually be made only after biopsy and careful histopathological evaluation of tissue, or by direct culture of Bartonella species from blood or the affected organ [20].

Cutaneous bacillary angiomatosis

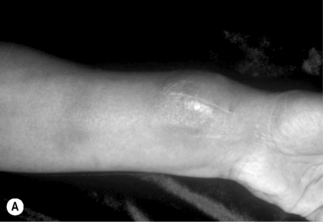

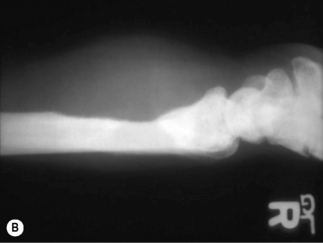

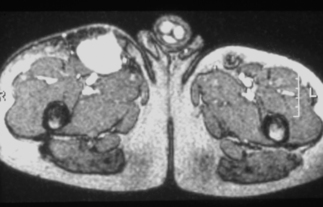

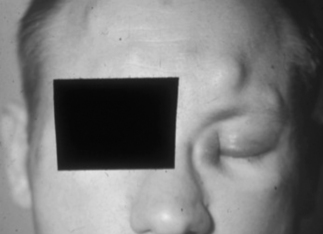

The most frequently diagnosed BA lesions are those affecting the skin [20]. Cutaneous BA lesions can have myriad presentations, including vascular proliferative lesions with a smooth red or eroded surface (Fig. 33.1, groin BA lesion) or papules that enlarge to form friable, exophytic lesions (Fig. 33.1, finger BA lesion). These vascular lesions of cutaneous BA are particularly difficult to distinguish clinically from Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), and thus histopathological examination of biopsied tissue is essential. BA may appear as a cellulitic plaque, usually overlying an osteolytic lesion (Fig. 33.2). Less vascular-appearing lesions can be dry and scaly (Fig. 33.3) and some lesions are subcutaneous, with or without overlying erythema (Fig. 33.4). BA lesions also can develop as very deep, highly vascular soft-tissue masses (Fig. 33.5) [16].

Figure 33.3 Unusual appearing erythematous, dry, scaling plaque of cutaneous BA mimicking staphylococcal pyoderma.

Bartonella quintana was cultured from this lesion.

(Reproduced with permission from Koehler JE, Tappero JW. Bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17:612–624.)

Figure 33.4 Multiple subcutaneous BA nodules in a patient with concomitant KS of the medial left eye canthus.

(Reproduced with permission from Koehler JE, Tappero JW. Bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17:612–624.)

Osseous bacillary angiomatosis

Bartonella infection of the bone causes osteolytic lesions that are extremely painful. The long bones, including tibia, fibula, and radius, are most commonly involved [20, 21], although osseous BA has occurred in a rib [21] and vertebra [22, 23]. A radiograph usually demonstrates well-circumscribed osteolysis and deep soft-tissue swelling (Fig. 33.2B). The BA lytic lesions can be detected by technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate bone scans, and bone scintigraphy allows screening of the entire skeleton for multifocal osteomyelitis [24]. Osseous BA should be a primary consideration in the differential diagnosis of a lytic bone lesion in HIV-infected patients.

Splenic and hepatic bacillary peliosis

Bacillary peliosis hepatis, a vascular lesion of the liver associated with infiltration of Bartonella bacilli, was first described in eight HIV-infected individuals by Perkocha and co-workers [15]. The symptoms of patients with BP hepatis usually include abdominal pain and fever. All eight patients had hepatomegaly, and six also had splenomegaly [15]. Two of the patients underwent splenectomy, and histopathological examination revealed BP of the spleen. One-quarter of the patients also had cutaneous BA lesions. The serum alkaline phosphatase was more prominently elevated than the hepatic transaminases in these patients with BP hepatis. In one HIV-infected patient, BP presented as massive hemoperitoneum and hypotension, and bleeding from the liver was the only source of hemorrhage that could be identified during laparotomy [25]. Abdominal CT of the peliotic liver usually reveals numerous hypodense lesions [20, 26] as shown in Figure 33.6, but this appearance is not specific for BP; thus the diagnosis of Bartonella infection must be confirmed by histopathological evaluation. Additionally, some HIV-infected patients with hepatic Bartonella infection develop inflammatory nodules in the liver without the vascular proliferative characteristics of peliosis hepatis [27]. Patients with splenic BP can have thrombocytopenia or pancytopenia and abdominal ascites [28, 29].

Gastrointestinal and respiratory tract bacillary angiomatosis

Histopathologically proven BA of the gastrointestinal tract has been described by several groups [30–32]. The lesions can involve oral, anal, peritoneal, and gastrointestinal tissue appearing as raised, nodular, ulcerated intraluminal mucosal abnormalities of the stomach and large and small intestine during endoscopy [31]. Extraluminal, intra-abdominal BA presenting with massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage has also been described [32]. Hemorrhage in this patient occurred when the highly vascular mass eroded through the small intestine; B. quintana was cultured from tissue obtained by transabdominal needle biopsy of the mass.

Bacillary angiomatosis lesions of the respiratory tract have been observed in the larynx [30, 33]; in one of these patients, the BA lesions enlarged to cause an asphyxiative death [30]. Endobronchial BA lesions have been visualized during bronchoscopy, and described as polypoid lesions located in the segmental bronchi and the trachea [34, 35]. Several of these patients also had cutaneous BA. Bartonella infection can also cause pulmonary nodules in the immunocompromised patient: a renal transplant patient with chemotherapy-induced immunocompromise developed high fever (41°C) and bilateral pulmonary nodules [36]. Bartonella henselae DNA was demonstrated in parenchymal lung nodule biopsy specimens.

Lymph node bacillary angiomatosis

Lymph node involvement has been described frequently in association with cutaneous lesions or peliosis of the liver or spleen [20]. In these cases, the lymph nodes most commonly affected are those draining the BA lesion, and histopathological examination may reveal angiomatous changes within the lymph node. In other cases, however, BA involves only a single or several lymph nodes, in the absence of cutaneous or other organ involvement.

Central nervous system manifestations of Bartonella infection

Bartonella infection has been associated with aseptic meningitis [19] or parenchymal brain masses [37] in HIV-infected individuals. A left temporal lobe mass due to BA developed in an HIV-infected patient with new onset of seizures and facial nerve deficit [37]. The etiology of the mass remained undetermined for 8 months until the patient developed a cutaneous BA lesion. Treatment with erythromycin led to resolution of the cutaneous lesion and neurologic deficit; the parenchymal mass decreased in size during antibiotic treatment. Another patient developed fever, headache, diabetes insipidus, and altered mental status with multiple, small contrast-enhancing brain lesions, including a single suprasellar lesion [38]. Examination of biopsied brain tissue revealed an inflammatory infiltrate primarily involving the leptomeninges, and clumps of bacillary organisms by Warthin–Starry staining. B. henselae DNA was amplified from the biopsy material. The lesions and symptoms resolved after treatment with doxycycline and rifampin.

Retinal disease can occur in patients with AIDS and infection with B. henselae. The manifestations are often more severe than those seen in immunocompetent patients and can include neuroretinitis and retinochoroiditis [39]. Warren and co-workers [40] described an HIV-infected patient who developed severe and progressive retinal disease that did not respond to treatment for Toxoplasma or CMV. Retinal biopsy revealed vascular proliferation consistent with BA. Sequencing of amplified DNA extracted from the biopsy specimen identified B. henselae DNA. The patient was treated with minocycline or doxycycline, with resolution of the retinitis and improvement in his visual acuity.

Unusual bacillary angiomatosis presentations

Several cases of BA involving the bone marrow have been reported [4, 28, 41]. Hepatosplenomegaly and thrombocytopenia were noted in both of these patients, and both resolved with antibiotic treatment. Venous thrombosis of the left upper extremity occurred in an AIDS patient with B. quintana bacteremia during relapse [16]. This was characterized by multiple non-contiguous, erythematous, tender superficial thromboses in the absence of trauma or intravenous drug use. All rapidly resolved after institution of antibiotic therapy.

Cutaneous BA complicating pregnancy in an HIV-infected woman was reported by Riley and co-workers [42]. Cutaneous lesions resolved after antibiotic treatment, and the subsequent pregnancy and delivery were uneventful. BA lesions have been described in several pediatric patients: one patient was immunocompromised due to chemotherapy [43]; the other was 3.5 years old and had been infected with HIV perinatally [44].

Bacteremia with Bartonella species and fever of unknown origin

Many patients with BA and BP also have Bartonella bacteremia. One-half of our patients with culture-positive focal BA or BP also had the corresponding Bartonella species simultaneously isolated from the blood [11]. Bartonella bacteremia in the absence of focal BA disease has been reported by a number of groups [5, 6, 45], and may be more common than focal Bartonella disease. In a study of 382 patients with fever of undetermined etiology, 68 patients (18%) had evidence of Bartonella infection by serology and/or culture. A total of 12 patients had bacteremia with B. henselae or B. quintana (six each) [45]. When examined carefully by a healthcare provider experienced in the recognition of BA, six of the 12 bacteremic patients were found to have lesions suspicious for BA, and the other six had isolated bacteremia without focal Bartonella disease. The median CD4 count was 33 cells/mm3 for the case patients in this study, indicating that both BA and Bartonella-related fever with bacteremia are usually identified in late-stage HIV infection. Also of note, endocarditis was described in one patient with HIV infection and culture-proven B. quintana [17].

Diagnosis of Bartonella Infections

Histopathological diagnosis

Obtaining tissue for diagnosis

Biopsy is the principal procedure available for the diagnosis of cutaneous BA. Because KS lesions can be clinically indistinguishable from those of BA, any new vascular lesion should be biopsied. In patients with previously diagnosed KS, any vascular lesion that has a different appearance or rate of growth should also be biopsied, because KS and cutaneous BA can occur simultaneously in the same patient [46]. Pedunculated lesions can be biopsied by shave excision, and smaller, papular, or subcutaneous lesions should be examined by punch biopsy. Biopsy of the cellulitic plaque that frequently overlies osteolytic lesions may be sufficient to yield a diagnosis of BA, but in some patients, open excisional bone biopsy is necessary [16]. Fine needle aspiration of BA lymph nodes has not been useful in diagnosis of BA in our center; thus, open excisional or incisional biopsy remains the optimal technique for diagnosis. For BP of the liver or spleen, the diagnostic procedure with greatest yield appears to be excisional wedge biopsy of the liver or splenectomy; however, peliosis hepatis has been diagnosed by either transvenous liver biopsy [47] or percutaneous liver biopsy [29]. As with cutaneous lesions, several opportunistic infections and malignancies can have a similar appearance on computed tomography of the abdomen; thus, biopsy is extremely important to direct specific treatment. No case of hemorrhage following percutaneous biopsy of a peliotic liver has been reported, although this remains a theoretical concern.

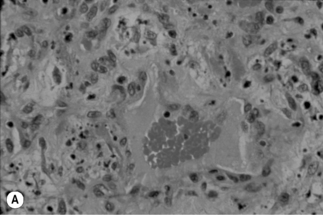

Histopathological characteristics

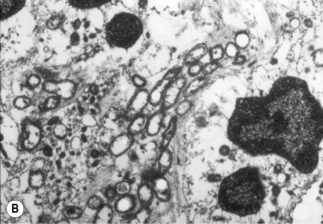

A characteristic vascular proliferation is seen on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining of BA or BP tissue (Fig. 33.7A). Numerous bacilli also can be demonstrated in these lesions by modified silver staining (e.g. Warthin–Starry, Steiner, Dieterle) or electron microscopy (Fig. 33.7B) [13, 15]. Other stains, such as those for tissue Gram-staining, fungi or acid-fast mycobacteria do not stain Bartonella bacilli.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree