Chapter 1 Australian and New Zealand healthcare and maternity services

Learning outcomes for this chapter are:

1. To define primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare

2. To explore why maternity services need to be recognised as primary healthcare rather than secondary and tertiary services

3. To investigate the relationship between health and the social structures and concepts of affluence, social wellbeing, education and social capital

4. To describe the structure and funding of New Zealand’s maternity services

5. To describe the structure and funding of Australia’s maternity services

6. To explain how funding models affect the provision of services and outcomes of care

7. To discuss the role of midwives within the New Zealand and Australian maternity services

8. To explore how maternity service models affect maternity outcomes for mothers and babies.

Maternal and Newborn Information System (MNIS)

National Minimum Dataset (NMDS)

National Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC)

The chapter discusses the role that midwives and women have played in the development of maternity services. It identifies how the maternity service structure in each country supports, or does not support, the provision of midwife-led maternity care and what effect it has on outcomes for maternity care for women and babies.

WHAT IS HEALTH?

Beginning in antiquity, there have been six key approaches to public health; their influences are still visible today. The first approach aimed to protect the community from disease through enforcement of society’s social structure such as religious and cultural rules and regulations—for example quarantine of leprosy sufferers (Leviticus 13) and illegal migrants, as well as theologically sanctioned rules about diet or hand washing. Beginning in the 1840s, during the Industrial Revolution, the era known as Miasma Control (Awofeso 2005) began. In 1848 Edwin Chadwick’s Report on An Inquiry into the Sanitary Conditions of the Labour Population in Great Britain was published. Chadwick demonstrated the overwhelming influence of filthy environmental conditions on adverse health outcomes. In fact, this early work laid the groundwork for contemporary epidemiology and health surveillance as well as legislation concerned with correct disposal of sewerage and refuse. In the 1880s Robert Koch, among others, postulated ‘germ theory’, demonstrating the presence of disease-causing bacteria in infected media and their pathogenesis.

The third era of public health was one of contagion control and heralded the beginning of evidence-based healthcare practice as well as the scientific basis for immunisation and chemotherapy. From the 1940s to the 1960s, the fourth era of public health introduced the concept of preventative medicine. Public health measures focused on ‘high risk populations’ such as pregnant women, the elderly and school children. Physicians began to play an increasingly important role in shaping political and public perceptions of healthcare policy and healthcare interventions (Awofeso 2005). The key elements of the fifth public health era, primary health care, were outlined in the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration. Its dominant paradigm is Health Care for All: effective healthcare geared towards the community, for the community, and by the community. This is achieved through primary healthcare as the first point of contact between people in the community and the healthcare system, and thus primary healthcare aims to be coordinated, universally accessible and available through a range of providers with appropriate skills.

The sixth public health era, known as the New Public Health or the era of health promotion, was ratified by the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986). It built on the progress made through the Declaration on Primary Health Care at Alma-Ata. However, the New Public Health is primarily concerned with the relationship between health on the one hand and social conditions such as affluence, social wellbeing and education on the other. Social capital, as the networks or relationships between social structures, both influences and is affected by the health of societies. While the New Public Health remains alarmed by all threats to health (including chronic disease and mental illness), it is increasingly focused on the sustainability and viability of the physical environment. Further, proponents argue that medicine is only one of the professions contributing to healthcare services and outcomes, so that sociologists, health economists, health promotion educators, midwives and nurses now share the limelight with public health physicians. The New Public Health advocates for health, enabling individuals and communities to attain optimal health, by: healthy public health policy; creation of supportive environments; strengthening of community action; development of personal skills and the reorientation of healthcare services towards health promotion (WHO 1986). In Australia and New Zealand the New Public Health has been reflected by the steady rise in health promotion. Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control and improve their health. ‘To reach a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, an individual or group must be able to identify and realise aspirations, to satisfy needs and to change or cope with the environment’ (WHO 1986).

DEFINITIONS OF HEALTHCARE SERVICES

Primary healthcare is the first level of service provision. It is usually the initial point of contact that people have with the healthcare system. Primary healthcare aims to be universally accessible to individuals and families in the community. Services are coordinated, accessible to all, and accessed through a variety of providers (not all of whom are healthcare professionals) who possess the appropriate skills to meet the needs of individuals and the community they serve.

MIDWIFERY AND PRIMARY HEALTHCARE

While New Zealand has a well functioning and integrated model of maternity care based in primary midwifery care, Australian maternity services are still based largely in secondary-care hospital facilities and in the primary medical care arena. However, many states are moving towards community and primary healthcare models to provide maternity services, including primary midwifery care. Australia is in the process of introducing major national maternity reforms which will enhance the provision of midwifery services in a primary healthcare model (Commonwealth of Australia 2009). Both countries have developed mechanisms for linkages between primary, secondary and tertiary maternity services, and these services and referral guidelines are described in the relevant service specifications issued by the Ministry of Health in New Zealand or by Australian state and federal departments of health.

PRINCIPLES OF PRIMARY HEALTHCARE

Care should be equitable and accessible

This principle espouses the notion of equity—resources should be distributed fairly according to need, with more directed at those who require it most. In 2010, even in comparatively rich countries there are still gaping inequities and social injustices between individuals, communities and states that leave large segments of the population without basic healthcare.

New Zealand’s maternity service is free and universally accessible, with every pregnant woman expected to have access to her own lead maternity carer (LMC) for the duration of her pregnancy, birth and puerperium regardless of her economic status. There is emerging evidence that this universal access has improved outcomes for women who are in the higher (most deprived) socioeconomic decile populations. The Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Report (2009) identifies that New Zealand’s perinatal mortality rates are low with no clear association between socioeconomic deprivation index and mortality outcomes (Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee 2009). This is the first reported major reduction in the equity gap between the wealthy and the poor since records have been kept.

Primary healthcare should include essential, appropriate activities

In New Zealand, midwives are the main providers responsible for referring mothers to the well child services for their babies to start their immunisation program at six weeks. Some 95% of babies receive their first vaccination, indicating an effective integration from maternity care into the next primary healthcare service, the well child service. Regrettably, this level of vaccination in infants is not maintained in the well child service, with coverage rates of between 65% at six months and 80% at 24 months reported. This is still short of the goal of full vaccination coverage of 95% of New Zealand children by the age of two years (National Immunisation Register, New Zealand 2009). Despite this drop in vaccination coverage in the well child service, the six-week example demonstrates that integration from service to service is a possible consequence of a well-organised one-on-one primary maternity healthcare service.

Care should be accessible and acceptable to everybody

Dr Lowitja O’Donoghue (1999), a prominent Australian Aboriginal activist, told her audience at a rural health conference that members of remote Aboriginal communities who are ill experience triple jeopardy. First, they are Aboriginal with all the socioeconomic disadvantages that go with that; second, many live far from

Clinical point

Maternity services are often most needed by those who cannot access them. Over 12% of Aboriginal people have to travel more than 100 kilometres to get to a hospital. More than half of Indigenous people living in rural Australia have to travel more than 50 kilometres to a hospital (O’Donoghue 1999). Many do not own or have access to vehicles. It is little wonder, then, that Aboriginal women are ‘poor attendees’ at antenatal clinics; they have no means of getting there. A hallmark of quality maternity care is a good transportation system to enable referrals to a higher level of care.

medical services. And finally, in rural and remote areas in particular, Indigenous people have little involvement in the healthcare services they can access; and even if they do, they feel alienated from mainstream facilities.

Primary healthcare should be affordable

The picture is very different in New Zealand, where all maternity care is free. All women expect to have their own LMC and 78% choose a midwife LMC (Ministry of Health 2009a). Women can choose where they give birth, and home birth is also fully funded. Women who do not require referral to specialist care can still choose a private obstetrician to be their LMC instead of the public obstetric service, although the private obstetrician is likely to charge a fee.

Primary healthcare should contribute to the self-reliance and self-determination of communities

Health bureaucrats and funding bodies often pay lip-service to the ideal of community participation in decision-making. Although structures for consultation may exist, stakeholders are rarely delegated any serious power or decision-making authority. Hence the wishes and priorities of the community are often buried in many layers of the consultation process. Moreover, a token ‘consumer’ on a Board of Health usually has little say in proceedings. For example, the Western Australian government consistently invites the community to join it in the identification of priority issues and to have input into the creation and implementation of programs to solve them (Thorogood 2001). However, the wishes of the community are often overruled if they are not in alignment with the needs of the powerful medical lobby.

There is good evidence (Barnett et al 2005) that community-based initiatives aimed at lowering maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality are effective, sustainable and more likely to achieve high coverage in the poorest communities than are secondary or tertiary hospital-based approaches. The Strong Women, Strong Babies, Strong Culture (SWSBSC) program (see Box1.1) is a good example of such an approach. The SWSBSC program provides health promotion through local women’s groups. This social intervention harnesses the creativity and self-organising skills of Indigenous women living in the Top End of Australia.

Box 1.1 Strong women, strong babies

The Strong Women, Strong Babies, Strong Culture Program

(Source: d’Espaignet et al 2003)

Box 1.2 Section 88 specifications

The service specifications of the Section 88 Notice provide that:

• LMCs receive written authorisation from the Ministry of Health to provide maternity services, as authorised practitioners, in order to be able to work under the conditions of the Notice.

• Payment is made to authorised practitioners via HealthPAC, the business unit of the Ministry of Health, which administers payment for primary care services.

• Each woman chooses an LMC, who works with the woman to assess, plan and provide her primary maternity care, coordinate and arrange access to additional care as required. This allows for continuity of carer throughout the maternity care episode.

• An LMC can be either a midwife, a GP with a diploma in obstetrics, or an obstetrician.

• Care is from the woman’s registration with an LMC to four to six weeks postpartum according to clinical need. There are four modules of care, with the expectation that all four will be provided by the same carer.

• In the first trimester prior to registration with an LMC and for all consultations with obstetric specialists, the service is funded on a fee-for-service basis.

• After the first trimester, the payment structure is modular and based on: the second and third pregnancy trimester; labour and birth; and postnatal care. Each module of care is capped at a set price but there various of mechanisms to enable LMC work to be recompensed if it falls outside these module definitions.

• Childbirth education other than the usual information provided by the woman’s individual LMC also has a separate budget, and a variety of educators contract with the Ministry to provide this service.

• A woman can only have one LMC at a time but there is provision for her to change at any time.

The choice of LMC depends to some extent on where a woman lives, as the full range of options is not available in all areas. There is a nationwide government-funded telephone service that provides women with information on LMCs available in their area. This is the 0800 MUM2BE number. The College also provides this service nationally. A full copy of the Maternity Advice Notice is accessible from the Ministry of Health website (www.moh.govt.nz) and more information about midwifery practice in New Zealand is available from the NZCOM website (www.midwife.org.nz).

Box 1.3 Community midwifery

The WA Community Midwifery Program, 1996–2005

(Source: Thiele & Thorogood 1998a, 1998b, 2001)

Critical thinking exercise

1. High rates of perinatal mortality are observed in Ethiopian-Australian babies born at an inner-city public hospital. What might be the reasons for this?

2. You have been asked to evaluate a Smoking Cessation Service for pregnant women. Think of how you could measure the following outcomes:

MIDWIFERY IS A PRIMARY HEALTHCARE WORKFORCE

The underlying principles of primary healthcare provision apply to maternity services. That is, services should be provided equitably and at the most accessible level of the healthcare system capable of performing them adequately. It is considered internationally that the person best equipped to provide community-based, appropriate technology, and safe and cost-effective care to women during their reproductive lives, is the person with midwifery skills who lives in the community alongside the women she attends (WHO 2004).

MIDWIFERY AND MATERNITY SERVICES IN NEW ZEALAND

New Zealand has a similar history to other Commonwealth colonies in the development of its maternity services. In the absence of an easily accessible healthcare service due to a scattered, isolated geographic environment, the maternity system was built from personal experience and women helping other women. Māori had a similar history of family/whānau-centred attendance at birth. As with non-Māori, the nature and style of Māori birth attendance differed with each hapū/iwi (family or tribe), depending on their experience and belief systems. In the 1800s and early 1900s there were women (or men for some iwi) who were considered midwives, although few had structured or formal education specific to midwifery. The introduction of midwifery regulation in 1904 was an attempt to provide a more formal framework for midwifery and to give women a better standard of maternity care. However, this support for midwifery was not to last. A fuller discussion on the early maternity systems can be read in the historical accounts provided by Philippa Mein-Smith (1986), Joan Donley (1986), Elaine Papps and Mark Olssen (1997), Jane Stojanovich (2004) and Sally Pairman (2005a, 2005b, 2006).

Historical background

As discussed earlier in this chapter, any maternity system must always be seen in the social and political context of the time, and then in the context of the healthcare system overall. In New Zealand the 1990s was a decade notable for economic reforms and considerable changes in the healthcare sector (Gauld 2001). These changes provided a context that was favourable to the development of the current maternity services model, and politically aware women and midwives were able to capitalise on these healthcare sector changes or ‘reforms’ to create the successful maternity service that New Zealand enjoys today (Pairman & Guilliland 2003).

Consumer voice

From the 1920s through the 1980s, women in consumer advocacy organisations voiced their concerns over maternity care. They did not like the impersonal, hospital-controlled birthing culture and they lobbied hard over many years for a more woman- and family-centred maternity service (Dobbie 1990). They identified a need for the midwife to be more visible, and demanded that she take a stronger role in providing maternity care (Strid 1987).

For most of these years the midwifery profession was submerged within the nursing profession and not well organised to use its collective voice. While some individual midwives, in particular the home-birth midwives, were very clear about what midwifery was and had solid links to the consumer movement, the profession overall was slow to align itself with women. However, as women’s organisations became stronger and more universal, midwives also became more organised, and by the late 1980s had become part of this women-led movement. Once politicised, women’s groups and the midwifery profession worked together to make birthing services a political issue that could not be ignored (Guilliland & Pairman 1995). Helen Clark, the then Minister of Health, not only understood the foundation of the women’s health movement but was also strongly focused on the essential role of primary healthcare. She was sympathetic to the view that birth was a normal life event that should be controlled by each woman and her family in their own community. She understood that in order for this to happen, women would need midwives who were educated and resourced in a way that would make this care available and effective (Guilliland & Pairman 2010).

Maternity choices pre-1990

Women accessed the maternity service mostly through the GPs, who confirmed pregnancy and then directed the care in a variety of ways. Some provided the care themselves, although (according to the Health Department’s submissions to the Maternity Benefit Tribunal in 1992) at best only about 20% ever offered a full maternity service (McKendry & Curtin 1992). A larger number offered antenatal services to 28 weeks gestation before referring the woman to the hospital clinic, private obstetric specialist or a GP colleague who did provide full care.

Medical ‘teams’ provided the hospital antenatal clinic service. An obstetrician, who delegated the majority of care to registrars or house surgeon trainees, led the teams; midwives provided support. There were very few instances of midwife-led clinics. Antenatal clinics were crowded and women waited hours to be seen. As was the case in most of the Western world, a woman could be seen by as many as 50 healthcare professionals during pregnancy, labour, birth and the postpartum period (Flint 1986). Fathers and other family members struggled to be involved, and the information provided was heavily risk averse and based on hospital and medical priorities. There was little reporting or analysis of maternity services or practitioner outcomes either regionally or nationally.

Care was also delegated when a woman was in labour. If women were ‘normal’, midwives conducted the births regardless of who the client was booked under, and this was considered the midwife’s role. Doctors could still claim the $300 ‘delivery’ fee even though they were not present. Prior to 1990, midwives, rather than GPs, medical trainees or obstetricians, conducted between 66% and 90% of normal births (NZCOM 1992). However, the rate and type of midwife-managed care depended on hospital protocols, the type of midwifery leadership, the number and availability of obstetricians and the influence that obstetrics had over service delivery. It seldom relied on women’s wishes.

Medical education

As the medical specialty of obstetrics developed and grew during the 1970s and 1980s, obstetricians slowly displaced the GP in maternity care, particularly in urban hospitals. By 1990 most GPs referred to obstetricians for operative procedures such as forceps and other specialised interventions, as did midwives. Rural GPs kept their obstetric skills for longer but they too eventually dropped out of intrapartum care. A 1990 report to the Canterbury Area Health Board found that the GPs in Canterbury who did provide maternity care did so for an average of 10 women per year (Canterbury Area Health Board 1990). While the style and method of service delivery may have been different, the scope of practice of most GPs was essentially the same as that of midwives by 1990. General practitioners have been reluctant to acknowledge this. Furthermore, general practice struggled to attract new graduates to maternity service provision. From 1990 onwards there was a decrease in the number of GPs providing maternity services. This exit of GPs from providing intrapartum care was a worldwide phenomenon and had similar causes in each country. These causes included doctors being less willing to provide 24-hour care (also manifested in the establishment of arrangements to provide care outside of 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., such as after-hours clinics and sports clinics) and the perception that general practice was a low-income, lower-status choice than some of the highly specialised options in medicine.

Midwifery education

Midwives’ education prior to 1990 was based on a general and obstetric nursing qualification followed by the Advanced Diploma of Nursing (ADN) in which midwifery was a 12-week module. The ADN was theoretically focused on primary healthcare and midwifery philosophy but struggled to provide clinical experience outside the tertiary hospital system (Pairman 2002). Most midwives were unhappy with their training and in 1986 an overwhelming 88% trained overseas (Pairman 2002). Registered midwives were also disillusioned with their limited role, and increasing numbers left midwifery practice (Department of Education 1987). It had been clear to midwives for decades that midwifery education required a major review, and the 1990 Nurses Amendment Act paved the way for development of direct-entry degree-level midwifery education (Pairman 2002, 2005a).

The Nurses Amendment Act 1990

Government steps to improve the situation included strengthening the midwifery profession’s ability to provide continuity of care. The Nurses Amendment Act 1990 (NAA) enabled midwives to practise all the competencies within a midwifery scope of practice. Midwives could now offer women the full range of antenatal, labour, birth and postnatal services from conception to six weeks postpartum without the supervision of a doctor.

Midwifery’s right to claim from the MBS was challenged by the New Zealand Medical Association in 1992. The Minister of Health convened the Maternity Benefits Tribunal, and after a week-long legal hearing the Tribunal confirmed that midwives provided the same or similar services and outcomes for pregnant and birthing women as GPs. The Tribunal accepted the principle that if the work was the same then it must be of equal value, and therefore midwives were entitled to claim the same payment as medical practitioners from the MBS (Maternity Benefit Tribunal 1993).

The New Zealand College of Midwives

The College is the umbrella under which individual midwives and the profession as a whole are guided. It retains its primary functions of setting and maintaining professional standards, providing professional indemnity cover for practising midwives, and promoting to and providing New Zealand women with an effective and women-responsive midwifery service. The College provides a detailed framework for midwifery practice (NZCOM 2008a). This includes a statement of philosophy, definition of midwifery scope of practice, a code of ethics, detailed standards of practice, and decision points for midwifery care.

The College brings its professional voice to its other arms through representation on each structure. A midwife must be a member of the College in order to be able to access membership of the midwifery union (MERAS; see below) or the business arm (MMPO; see below) of the College. (See also ch 12.)

Contemporary maternity services in New Zealand

The New Zealand healthcare system

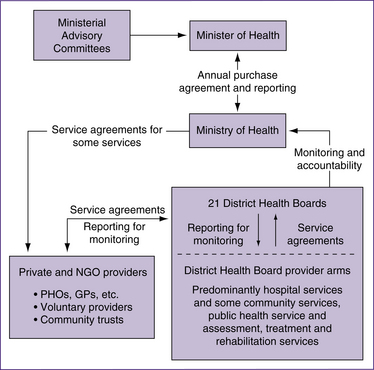

At the time of writing community (primary) maternity and well child services remain outside the management of the regional DHBs and the PHOs, and are funded nationally by the Ministry of Health. Other nationally operated services that affect maternity services in general include: the National Screening Unit which directs policy for all the national screening programs (such as cervical, breast, HIV and antenatal screening); the New Zealand Health Information Service, which manages the health data provided by hospitals and healthcare professionals (such as midwives and GPs); HealthPAC, the payment arm of the Ministry, which pays health providers for services; and the National Health Committee, which advises the Minister on policy issues.

The maternity service

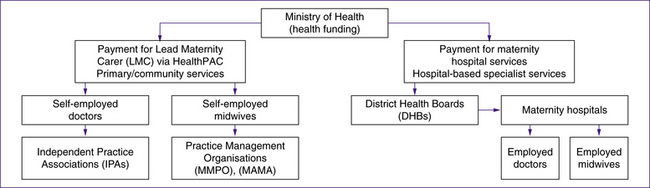

Figure 1.1 The structure of New Zealand’s health system, 2008

(based on Structure of the New Zealand health and disability sector, Ministry of Health, www.moh.govt.nz)

Vision for the maternity service

The influence of New Zealand’s pioneering women and midwives is obvious in this statement. The health system, including maternity, is overseen by a strong code of patients’ rights and a culture of informed consent. In 2010 New Zealand has a free maternity service, with equity of access for women to all the levels of care required. These levels of care cover primary care in the community and hospital-based specialist or secondary and tertiary care. All levels of service cross the geographic boundaries of 21 different DHBs and numerous PHOs. See Figure 1.2 for the funding mechanisms of New Zealand’s maternity services.

The majority of women can have an LMC to provide and coordinate their maternity care, develop a care plan with them and attend their labour, birth and postpartum period of up to six weeks. The LMC service is a primary healthcare one and therefore is provided mainly in the community. Most antenatal care is in women’s homes or in community clinics. If not birthing at home, the majority of women in the first 12–48 hours following birth have their postnatal care in the hospital or birthing unit but then receive visits at home for four to six weeks. This primary healthcare service is centrally funded by the Ministry of Health, and LMCs claim from the Ministry for their service fees. When a woman requires additional medical or hospital care her LMC can choose to provide the care herself, arrange additional medical or other specialist carers but continue to provide midwifery care, or transfer the care to a hospital team including obstetricians, midwives and paediatricians.

In 2009 the Ministry of Health consulted on a national maternity strategy as a result of disquiet in the sector regarding variances between DHBs and inequity of service provision as a result of workforce shortages. While the current draft circulating is a reframing and simplifying of the original vision, it does reaffirm the woman-centred LMC model of care which is based on childbirth as a normal life event (Ministry of Health 2009b).