Assessment of the baby

Assessment at birth

Learning outcomes

Having read this chapter, the reader should be able to:

There are two components to assessing the baby at birth – the Apgar score which is undertaken to determine how well the baby is adjusting from intrauterine to extrauterine life, and the top-to-toe physical examination that looks to confirm normality and detect any deviations from this so that referral can be made. These examinations are usually undertaken by the midwife as part of the care of the baby at birth (NICE 2014); thus it is important the midwife is competent in both of these assessments and understands the significance of what is being assessed and the findings. This chapter focuses on the assessments of the baby at birth, how they are undertaken, what is looked for, and the significance of what is found. Although in some countries the midwife will undertake a fuller examination to include looking for the red eye reflex, examining the hips for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), palpating femoral pulses, listening to the heart and lungs, and palpating the abdomen for organomegaly, this is only undertaken in the UK if the midwife has had further training and thus these aspects are not discussed within this chapter.

The Apgar score

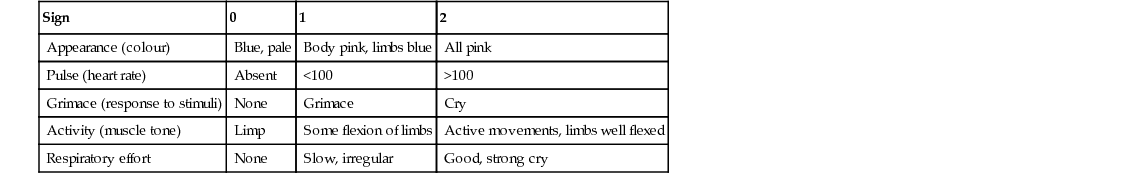

The Apgar score was formulated by Dr. Virginia Apgar in the 1950s as a way of assessing the baby’s condition at birth and the need for resuscitation. Five inter-related variables, assessed at 1, 5, and 10 minutes (although these can be repeated at different time frames), are based on what happens and can be seen if the baby does not breathe effectively at birth (Pinheiro 2009). Each of the five variables is given a score of 0, 1, or 2 with a total score out of 10 (Table 37.1). The variables are breathing, heart rate, colour, tone and reflex irritability. If the baby is not breathing, there is less oxygen reaching cardiac tissue causing the heart rate to decrease which results in less oxygen reaching the tissues. This will affect the colour, muscle tone, and reflex irritability. Thus a low score will indicate the need for resuscitation. As breathing occurs, the heart rate improves resulting in the baby becoming pinker, improved muscle tone, and reflex irritability. A high score reflects a baby who does not need resuscitation and can reflect the baby who has made the adjustment well or has had a good response to resuscitative measures undertaken. However, it must be remembered that resuscitation should begin before 1 minute if indicated by the condition of the baby and an Apgar score calculated during resuscitation is not equivalent to that of a baby who is breathing spontaneously. There is no accepted standard for calculating Apgar scores for babies who are being resuscitated (Pinheiro 2009).

A low score at 1 minute does not correlate with future outcome, whereas at 5 minutes it is associated with neonatal mortality from 24 weeks’ gestation, but there is conflicting evidence around neurological disability (Lee et al 2010, Li et al 2013, O’Donnell et al 2006, Pinheiro 2009). Iliodromiti et al (2014) found an increased risk of infant death for babies who had a 5-minute Apgar score of 0–3.

Dijxhoorn et al (1986) suggest changes in the fetal heart rate do not compare well with Apgar scores at delivery, making it difficult to anticipate which babies will have a low score at birth. This may account for why some emergency caesarean sections undertaken because of serious concerns regarding the fetal heart rate deliver a baby with a total Apgar score of 9 or 10. Additionally a persistently low Apgar score on its own should not be considered a specific indicator of intrapartum asphyxia. Salustiano et al (2012) undertook a retrospective study to assess risk factors associated with an Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes and found prolonged second stage of labour and repeated late decelerations on the cardiotocograph (CTG) were predictive but age, parity and breech birth were not. They also found these babies had an increased risk of respiratory distress, mechanical ventilation, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, and a strong association with hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy (Salustiano et al 2012).

The Apgar score is vulnerable to bias, as it is a subjective score and is often undertaken retrospectively. McCarthy et al (2013) found that babies being resuscitated were given an Apgar score at 1 minute even though there was no documented evidence that the heart rate had been recorded and suggest the score does not accurately reflect the events occurring during resuscitation or when interventions are occurring. Ideally it should be undertaken by someone other than the midwife in attendance at the birth, as the midwife can be distracted by what is happening to the mother and the baby. The retrospective scoring is often based on what happened to the baby; thus a baby who had no resuscitative measures will score high. In some situations the Apgar score is jointly assigned by all midwives and doctors present at delivery but again is often retrospective and O’Donnell et al (2006) caution there is poor interobserver reliability even when undertaken independently.

There are a number of factors that can influence the score, e.g. the quality of lighting can affect the perception of the baby’s colour as can skin pigmentation and haemoglobin levels. Tone can be affected by gestational age, congenital abnormality and maternal drugs. Silverton (1993) advises that skin pigmentation in non-Caucasian babies usually develops from the fifth day of life which can make these babies appear less well perfused. If the skin is darkly pigmented, colour can be assessed by observing the mucous membranes, palms of the hand, and soles of the feet, as these should be pink. The preterm baby has an immature neurological system resulting in poorer muscle tone and slower reflexes, as well as a bluish-red skin colour, which can lead to a low Apgar score, even though the baby requires no resuscitation.

Assessing the Apgar score

The five variables have been made into the acronym ‘APGAR’ – appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration.

The scores are added and a total score is documented. Babies scoring above seven rarely need resuscitation.

Birth examination

The initial birth examination is a physical examination undertaken to confirm normality and detect deviations from normal and is part of the midwife’s competencies (NMC 2010). It is usually undertaken within the first couple of hours of life, having given the baby time for skin-to-skin contact with his mother and to complete his first feed (NICE 2014). The examination should be undertaken in a warm environment, free from draughts (to ensure the baby does not become cold), and with a good light source. This examination is likely to reveal obvious abnormalities but others, some of which may not be apparent at birth, will be detected during the physical examination undertaken within the first 72 hours of birth (NSC 2008) by a midwife who has undertaken further training and assessment in the examination of the newborn (NMC 2012) or a paediatrician.

The midwife will develop her own systematic approach to examining the baby, the order is less important than ensuring the examination is thorough and complete.

PROCEDURE: birth examination

■ thermometer suitable for use with a baby (p. 35)

■ scales for weighing the baby

■ nappy.

• Wash and dry hands and put on non-sterile gloves.

• Dispose of disposable sheet and gloves, wash and dry hands.

• Discuss the findings with the parents during the procedure or at the end if they are not present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree