CHAPTER 9 Assessment in clinical education

USING THEORIES TO DRIVE EDUCATION METHODS

Example: The Assessment of Physiotherapy Practice (APP) is presented as a practical example of developing clear criteria that can be linked to explicit and detailed performance indicators. These performance indicators have been developed to reduce assessor bias and to provide students with clear practice goals. Such detailed and transparent expectations grounded in the realities of students’ learning experiences assist them to ‘unpack’ and make sense of their professional discourse and clinical practice. The assessment tool encourages students to reflect on their own performance in relation to the explicit behavioural descriptions.

Assessment drives learning

Assessment should impact positively on future learning (van der Vleuten 1996). It provides targets that focus and drive the depth and direction of learning for students. For educators, assessment provides opportunities for feedback to students on current performance, and enables the development of specific strategies to improve performance and achieve learning outcomes. Assessment targets include the foundation knowledge of health sciences, clinical skills and important domains of practice such as habits of reflection and professional behaviour, interpersonal skills, commitment to lifelong learning, and integration of relevant and current knowledge into practice (Epstein 2007, Epstein & Hundert 2002).

Methods used for assessing professional competence

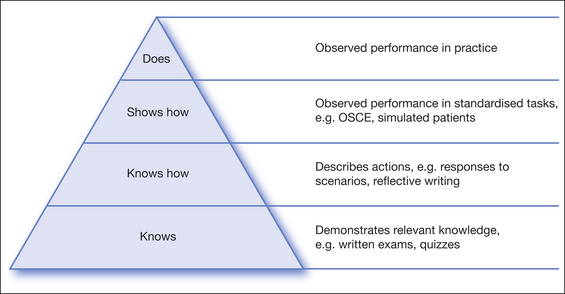

In 1990 psychologist George Miller proposed a pyramid of hierarchy in the assessment of clinical competence. From lowest to highest, the levels were defined as knows, knows how (competence), shows how (performance), and does (action) (Fig 9.1). Assessment of the highest level of ‘action’ involves identifying acceptable performance during typical practice. Rethans et al (2002) draw a clear distinction between (1) competency-based assessments or measuring what is done in testing situations, and (2) performance-based assessments, measuring what is done in practice. Important differences between the two are that competency assesses what is known and uses known conditions, equipment and methods, but performance in practice requires dealing with emotional states, uncertainty, complex circumstances and ongoing changes in systems of service provision and expectations. Performance-based assessments are also predicated on sociocultural theories of learning in which learning is understood as a process of participation in activities situated in appropriate social and cultural contexts (Lave & Wenger 1991). Wass et al (2001) called assessment of the pyramid apex (Fig 9.1) the ‘does’, as ‘the international challenge of the century for all involved in clinical competence testing’ (p 948). This chapter will focus on methods of performance assessment.

Professional education programs typically assess across all levels of clinical competence and include direct assessment of clinical practice. It is assumed that observed practice in the operational context is an indicator of likely professional performance (Wiggins 1989, p 711). The assessment of ‘does’ is required for certifying fitness to practice. Professional practice necessitates understanding and dealing with highly variable circumstances, and assessment is therefore difficult to standardise across students (Rethans et al 2002). A proposed solution to this complexity is to monitor students over a sufficiently long period of time to enable observation of practice in a range of circumstances and across a spectrum of patient types and needs. This has been argued as superior to one-off ‘exit style’ examinations (van der Vleuten 2000). It also enables assessment to encompass local contexts, cultures and workplaces within which learners must demonstrate competence (see Ch 3). Longitudinal monitoring is a form of longitudinal assessment that guides the evolution of professional habits such as reflective practices and ongoing learning. Longitudinal assessment can be subtle and continuous or intermittent and structured.

Formative and summative assessment

In broad terms, assessment can be applied in two ways: to determine competence and to guide skill development. Occasions that provide feedback on performance but are not graded (formative assessment) enable students to attempt the task without the confounding influence of fear of failing. Formative assessment outcomes guide future learning, provide reassurance, promote reflection and shape values (Epstein 2007, Molloy 2006). However it needs to be frequent and constructive (Boud 1995, Epstein 2007). Students need regular, clear and behaviourally specific feedback based on the educator’s assessment of their performance in order to devise and implement strategies to effect positive change.

Other important elements of formative assessment are that it should mimic graded (summative) assessment to familiarise the student with both the expected performance and their current skill levels, and to aid in devising a path for improving performance. When formative assessment mimics summative assessment, anxieties associated with summative assessment can be reduced through clarification of desired performance. Formative assessment provides a vehicle for the important work of gathering evidence of student learning in a way that supports the learning process (Masters 1999, p 20). As described in Chapter 8, learning through feedback, as a form of formative assessement, enables constructive discussion about student practices in a supportive environment where strategies to decrease anxiety and facilitate enquiry are deliberately introduced. These elements are important for students at all levels of achievement and are particularly important when the student is in danger of failing summative assessments. Learning through interaction and discussion is enhanced because formative assessment is less likely to invite a defensive reaction about student ability, as might occur in summative assessment where the effect on a student’s grade can create anxiety.

A further important element is the timing of formative assessment. Ideally it should be provided to enable adequate opportunity for skill development prior to summative assessment so as to further reduce associated anxiety and enable the planning of effective strategies that can be tested and modified to achieve learning goals. An important outcome of formative assessment is documentation of evidence of what was discussed so that all parties are very clear about the behaviours that would signal improved performance. Educators and students can crystallise the elements in performance that require attention and convert these to achievable goals.

Current practice in assessment of competency in allied health professions

Despite extensive literature on the issues underlying the assessment of clinical competence, the choice of assessment approach is typically influenced by historical precedents and the personal experiences of assessors, rather than known psychometric properties of assessment instruments (Newble et al 1994). Given the high stakes of undergraduate summative assessments of clinical competence, assessment procedures should not only be feasible and practical but also demonstrate sufficient reliability and validity for the purpose (Epstein & Hundert 2002, Roberts et al 2006, Wass et al 2001). Standardisation of clinical performance may be confounded by difficulties associated with unavoidable variations in test items, assessors, patients and examination procedures (Roberts et al 2006). Specific difficulties have been reported in relation to:

Concerns regarding valid and reliable measurement of student competencies when assessing workplace performance has in the past led to medical education emphasising standardised and controlled assessments such as Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) and the use of standardised patients. Other professions, including nursing (Govaerts et al 2002) and physiotherapy, have followed suit. While reliability of assessment will be enhanced by the standardised testing, the validity of such controlled examination procedures has been challenged because, as proposed earlier and highlighted in Chapter 3, competence under controlled conditions may not be an adequate surrogate for performance under the complex and uncertain conditions encountered in usual practice. In addition, important professional attributes such as reflection and willingness to learn and adopt new practices is not easily assessed under controlled conditions.

Norcini (2003a) argues that we should develop and refine performance-based assessments. Ideal assessment procedures should facilitate evaluation of the complex domains of competency in the context of the practice environment within which competence is desirable. Assessment of habitual performance in the clinical environment is essential for making judgements about clinical competence and professional behaviours and, importantly, for guiding students towards expected standards of practice performance (Govaerts 2002). In addition, a more longitudinally or context-based assessment enables the important sociocultural perspective of learning to be addressed as students are able to construct their own learning within the context-specific clinical environment (Sfard 1998).

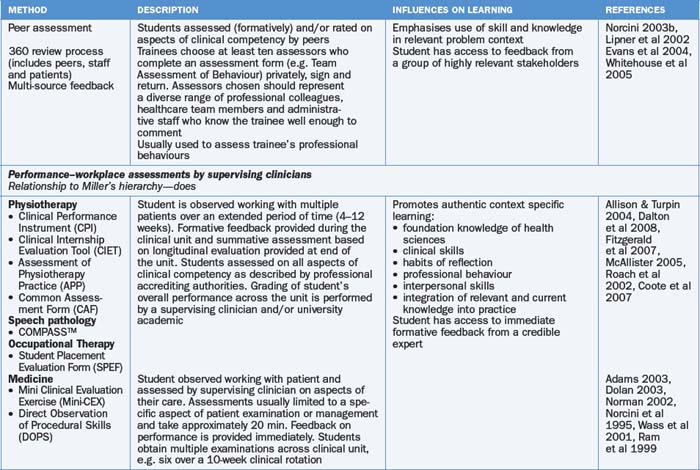

This rationale provides a catalyst for ongoing research into robust and valid assessment instruments and procedures, and was the driver for establishment of the APP tool presented in this chapter. Table 9.1 provides a summary of methods that have been reported for assessing competency in the health professions. All methods of assessment have intrinsic strengths and weaknesses, and assess different aspects of Miller’s hierarchy (1990).

Maximising assessment that improves performance

It is often assumed that providing ongoing feedback as a form of formative assessment is both natural and easy, but student feedback and previous literature indicates that it is frequently done quite poorly (Ende et al 1995, Hewson & Little 1998). To provide consistently useful assessment and feedback, educators need to monitor their attitudes and biases, the way they design targets for student skill development, and the way they utilise language. Assessment and feedback about assessment can be confounded by educator feelings such as negativity, anxiety, frustration, lack of confidence in their own skills in some areas, or even positive regard for the student. Educators are likely to benefit from opportunities and strategies to use to reflect on the way they assess students. For example, the SMART model proposes that assessment should be delivered using methods that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timely (Drucker 1954). These attributes require educators to reflect on how to provide feedback that describes desirable behaviour.

Borrell-Carrió and Epstein (2004) articulate a range of factors that might reduce the quality of clinical decisions and professional performance. These might also be considered as factors that impact on assessment in the clinical environment. Clinical educators are particularly vulnerable to effects of fatigue and of feeling overwhelmed by workload, factors that might translate into an urgency to finish a task or a lack of motivation to model the highest possible standards. Added to this, patient needs and behaviours can complicate the interaction between clinician and student if the clinician feels intimidated or annoyed by patient or student anxiety or hostility.

Educators might be vulnerable to retreating behind what Borrell-Carrió and Epstein (2004) describe as ‘low-level decision rules’. These are positions that are taken without reflective evaluation of needs and goals specific to the situation. Some examples are provided in Table 9.2 to illustrate the point and provide non-prescriptive examples of possible alternative (high-level) decisions.

Table 9.2 Applying high- and low-level decision rules (Borrell-Carrió & Epstein 2004) to evaluation of student needs

| LOW-LEVEL DECISIONS | HIGH-LEVEL DECISIONS AND REFLECTIVE HABITS |

|---|---|

| As soon as I met him I knew he was lazy | This student needs strategies to develop attention to desirable performance indicators |

| She is a good student and can be left to manage patients on her own | This student requires high-level challenges to maintain her motivation and promote development |

| She is very defensive when I give feedback and does not listen to me | I will write down what you have said and reflect on it and we can discuss this again tomorrow |

| She really shouldn’t be here. She doesn’t have enough theoretical knowledge | Why not take some time to re-familiarise yourself with the following learning objectives and we will repeat this challenge tomorrow |

| He is not acting professionally | For this student I need to explicitly define areas of professional development that require attention and clearly communicate my expectation about the way in which they need to improve |

| I got quite angry with the student because they had not adequately prepared for the situation | |

| I don’t have time to go over this again, I have a lot of patients to see | How could I be more present with and available to this student? |

| He is much better than she is | Were there any points at which I felt judgemental about the student in a positive or negative way? |

| He is not improving, no matter how much help I give him | If there were relevant data that I ignored, what might they be? |

Recognising challenges and bias in the assessment of students

Formative assessment that mimics summative assessment provides the educator with important opportunities to reflect on their own biases that might work for or against the student. If educators recognise there are circumstances such as fatigue or overload that render them vulnerable to retreating behind low-level decisions and responses, they are in a position to introduce habits that facilitate high-level decisions. Borrell-Carrió and Epstein (2004) suggest strategies for minimising practice errors that might be considered in this context. Educators might reflect on when they are at risk of cognitive distortion, prematurely closing on a teaching encounter that warrants additional attention or the use of ‘low-level decision rules’ and detecting moments when it is necessary to ‘reframe the interaction’. As part of basic training in clinical education, a teacher might develop some habitualised cognitive, emotional, and behavioural skills, such as methods to detect states of low cognition and emotional overload, that could lead to dismissing rather than attending to needs of students. Educators could be assisted to cultivate an awareness of states of fatigue and the potential for such fatigue to limit capacity for high-level decisions. They could learn the skill of stepping back from a situation when interaction with the student has ceased to be productive or their ability to provide quality assessment is poor. Leaving a non-productive interaction can enable the opportunity to revisit the interaction at a time when re-engagement or a new perspective is possible. Practical strategies include slowing down, recommending the interaction is deferred to a period following rest or reflection, discussing options with more experienced colleagues, placing a pause into an interaction to enable learning a new pattern of response, and reflecting on the goal of the education process rather than the detail of a specific interaction (Borrell-Carrió & Epstein 2004). In addition to workplace pressures that might induce less than ideal conditions at the educator–student interface, both student and educator are vulnerable to a number of well-documented biases that can affect formative assessment. If an educator allows a global bias about a student (either negative ‘devil effect’ or positive ‘halo effect’) to operate beneath interactions, it may be difficult to accurately assess, reward or guide development of performance.

A devil effect would occur if an educator had negative views about an undesirable trait in a student, and this influenced their approach to subsequent interactions and assessments. A simple example would be if a student did not make eye contact and said little during discussions. The educator may assume indifference on the student’s part, and judge performance more harshly than they would if they perceived the student as friendly and engaged. The devil effect can also operate to create an impression the student may not be able to rectify. To illustrate with a simple example, at their first clinic the student arrived five minutes late several times in the first week. The educator discusses expectations of punctuality and the student, recognising a need for adjustment in less than rigorous habits, subsequently arrives five minutes early every day for the remainder of the clinic. If the student received a summative report that included a drop in grades associated with punctuality, they would have reason to be unhappy. Anecdotally, students make frequent complaints that these ‘sustained judgements’ are commonplace. A devil effect can tarnish educator perspective and lead to inaccurate assumptions. Gilbert & Malone (1995) refer to this as assumption bias about student motivation or ability that can be difficult for the student to counter. A reflective educator might use tricks such as those proposed by Borrell-Carrió and Epstein (2004) to limit the potential for bias to thread its way across repeated assessments.

Outcome bias may be another important source of bias for assessors to consider. This bias influences people to judge a decision more harshly if they are aware of a bad outcome than they would judge the same decision if they are unaware of the bad outcome (Henriksen & Kaplan 2003). In clinical education, a student whose decision or performance results in patient complications (or improvements) is likely to be assessed more harshly (or favourably) than if there were no observable consequences arising from those actions. Judging single decisions on the basis of their outcomes is problematic because the student has not had a chance to demonstrate learning or reflection arising from knowledge of the outcome. It is also inaccurate because it uses information that was not available at the time the decision was made. Assessing the quality of decisions should be confined to assessment of the way the student approached the problem and its solution.

Reflecting on sources of cognitive bias, and where they might operate in a person’s life, is an important step in controlling the dominance that these biases can have over perceptions. A change in stimulus intensity might change educator responses from enjoyment to displeasure, or from cooperative to competitive emotions. A student repeatedly asking the same question or requesting help for the same skill development might change an educator’s reaction from interest to irritation. Educators will naturally seek a cognitive alibi for their behaviour and may categorise the student to explain their irritation: ‘She has a very irritating manner with the patient’, or ‘He is a very slow learner’. This type of categorisation might enable premature closure on evaluation of the educational opportunities in a situation, and stifle the relationship required for fruitful modelling of high-level decision making and professional behaviour. It is at this point that the advantage of a reflective approach to the role and responsibilities of the educator and student might enable more thoughtful and productive responses to the student, and assist with developing suitable strategies to deal with apparent difficulties.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree