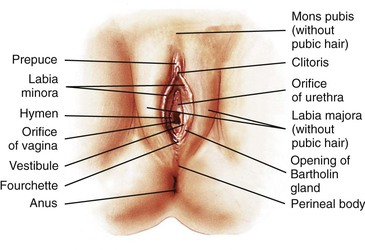

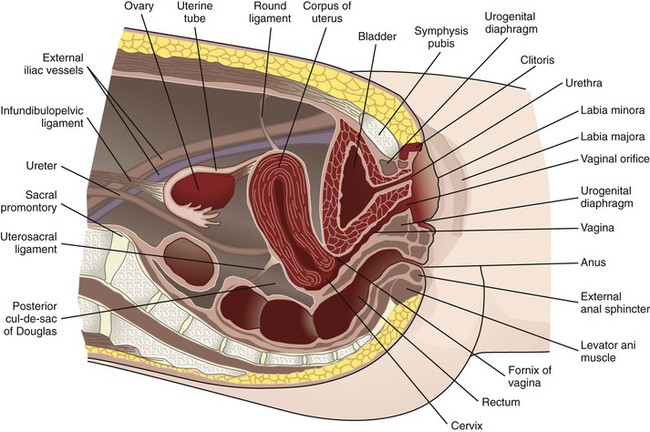

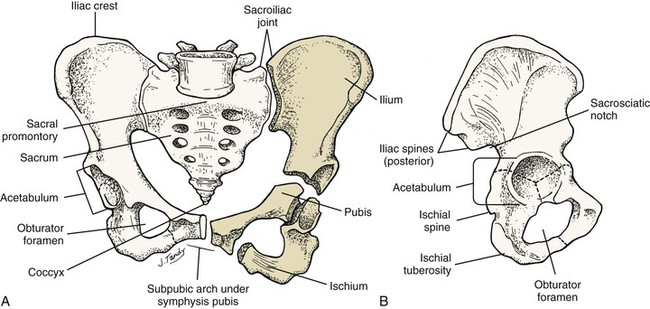

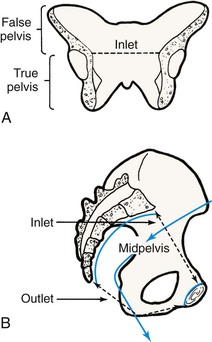

• Identify the structures and functions of the female reproductive system. • Compare the hypothalamic-pituitary, ovarian, and endometrial cycles of menstruation. • Identify the four phases of the sexual response cycle. • Identify the reasons why women enter the health care delivery system, including preconception care. • Discuss the financial, cultural, and gender barriers to seeking health care. • Explain the conditions and characteristics that increase health risks, specifically age, substance abuse, nutritional and physical status, medical conditions, and intimate partner violence. • Outline the components of taking a woman’s history and performing a physical examination. • Discuss how the assessment and physical examination can be adapted for women with special needs. • Identify the correct procedure for assisting with and collecting specimens for Papanicolaou testing. • Review health promotion and prevention suggestions for common health risks. Additional related content can be found on the companion website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/Maternity/ • Anatomy Review: Adult Female Pelvis • Anatomy Review: External Female Genitalia • Anatomy Review: Female Breast • Anatomy Review: Female Pelvic Organs • Animation: Female Accessory Sex Glands • Animation: Female External Genitalia • Animation: Female Reproductive Ducts • Animation: Menstrual Cycle: Uterine • Case Study: Health Assessment • Critical Thinking Exercise: Women’s Health and Safety • Nursing Care Plan: The Battered Woman • Skill: Breast Self-Examination • Spanish Guidelines: Menstruation • Spanish Guidelines: Physical Examination • Spanish Guidelines: Recognizing Violence in a Relationship The external genital organs, or vulva, include all structures visible externally from the pubis to the perineum (Fig. 2-1). The mons pubis is a fatty pad that lies over the anterior surface of the symphysis pubis. In the postpubertal woman, the mons is covered with coarse curly hair. The labia majora are two rounded folds of fatty tissue covered with skin that extend downward and backward from the mons pubis. These folds are highly vascular structures that develop hair on the outer surfaces after puberty and protect the inner vulvar structures. The labia minora are two flat, reddish folds of tissue visible when the labia majora are separated. Anteriorly, they fuse to form the prepuce (a hoodlike covering of the clitoris) and the frenulum (a fold of tissue under the clitoris). The labia minora join to form a thin flat tissue called the fourchette underneath the vaginal opening at the midline. The clitoris is a small structure composed of erectile tissue with numerous sensory nerve endings located underneath the prepuce. The vaginal vestibule is an almond-shaped area enclosed by the labia minora that contains openings to the urethra, Skene glands, vagina, and Bartholin glands. The urethra is not a reproductive organ but is considered here because of its location. Usually this structure is approximately 2.5 cm below the clitoris. The Skene glands are located on each side of the urethra and produce mucus, which aids in lubrication of the vagina. The vaginal opening is in the lower portion of the vestibule and varies in shape and size. The hymen, a connective tissue membrane, surrounds the vaginal opening. Bartholin glands (see Fig. 2-1) lie under the constrictor muscles of the vagina and are located posteriorly on the sides of the vaginal opening, although the ductal openings are not usually visible. During sexual arousal the glands secrete clear mucus to lubricate the vaginal introitus. The uterus is divided into two major parts: an upper triangular portion called the corpus and a lower cylindric portion called the cervix (Fig. 2-2). The fundus is the dome-shaped top of the uterus and is the site where the uterine tubes enter the uterus. The isthmus (lower uterine segment) is a short, constricted portion that separates the corpus from the cervix. The uterine wall consists of three layers: the endometrium, the myometrium, and part of the peritoneum. The endometrium is a highly vascular lining made up of three layers, the outer two of which are shed during menstruation. The myometrium is made up of layers of smooth muscles that extend in three different directions (longitudinal, transverse, and oblique) (Fig. 2-3). Longitudinal fibers of the outer myometrial layer are mostly in the fundus, and this arrangement assists in expelling the fetus during the birth process. The middle layer contains fibers from all three directions, which form a figure-eight pattern encircling large blood vessels. This arrangement assists in constricting blood vessels after childbirth and controls blood loss. Most of the circular fibers of the inner myometrial layer are around the site where the uterine tubes enter the uterus and around the internal cervical os (opening). These fibers help keep the cervix closed during pregnancy and prevent menstrual blood from flowing back into the uterine tubes during menstruation. The outer cervix is covered with a layer of squamous epithelium. The mucosa of the cervical canal is covered with columnar epithelium and contains numerous glands that secrete mucus in response to ovarian hormones. The squamocolumnar junction, where the two types of cells meet, is usually just inside the cervical os. This junction is also called the transformation zone and is the most common site for neoplastic changes. Cells from this site are scraped for the Papanicolaou (Pap) test (or smear) (see p. 51). The bony pelvis serves three primary purposes: protection of the pelvic structures, accommodation of the growing fetus during pregnancy, and anchorage of the pelvic support structures. Two innominate (hip) bones (consisting of the ilium, ischium, and pubis), the sacrum, and the coccyx make up the four bones of the pelvis (Fig. 2-4). Cartilage and ligaments form the symphysis pubis, sacrococcygeal, and two sacroiliac joints that separate the pelvic bones. The pelvis is divided into two parts: the false pelvis and the true pelvis (Fig. 2-5). The false pelvis is the upper portion above the pelvic brim or inlet. The true pelvis is the lower curved bony canal, which includes the inlet, the cavity, and the outlet through which the fetus passes during vaginal birth. Variations that occur in the size and shape of the pelvis are usually a result of age, race, and injury. Pelvic ossification is complete by approximately 20 years of age. The breasts are paired mammary glands located between the second and sixth ribs (Fig. 2-6). Approximately two thirds of the breast overlies the pectoralis major muscle, between the sternum and midaxillary line, with an extension to the axilla referred to as the tail of Spence. The lowest third of the breast lies over the serratus anterior muscle. Connective tissue called fascia attach the breast to the muscles. Findings from several studies using ultrasound imaging to investigate the anatomy of the breast found differences from previous descriptions (Geddes, 2007; Love & Barsky, 2004; Ramsay, Kent, Hartmann, & Hartmann, 2005). Each mammary gland is made of a number of lobes, which are divided into lobules. Lobules are clusters of acini. An acinus is a saclike terminal part of a compound gland emptying through a narrow lumen or duct. The acini are lined with epithelial cells that secrete colostrum and milk. Just below the epithelium is the myoepithelium (myo, or muscle), which contracts to expel milk from the acini. The ducts from the clusters of acini that form the lobules merge to form larger ducts draining the lobes. Ducts from the lobes converge in a single nipple (mammary papilla) surrounded by an areola. The anatomy of the ducts is similar for each breast but varies among women. Protective fatty tissue surrounds the glandular structures and ducts. Cooper’s ligaments, or fibrous suspensory, separate and support the glandular structures and ducts. Cooper’s ligaments provide support to the mammary glands while permitting their mobility on the chest wall (see Fig. 2-6). The round nipple is usually slightly elevated above the breast. On each breast the nipple projects slightly upward and laterally. It contains 4 to 20 openings from the milk ducts. The nipple is surrounded by fibromuscular tissue and covered by wrinkled skin (the areola). Except during pregnancy and lactation, there is usually no discharge from the nipple. The nipple and surrounding areola are usually more deeply pigmented than the skin of the breast. Sebaceous glands called Montgomery tubercles directly beneath the skin (see Fig. 2-6) give the areola its rough appearance. These glands secrete a fatty substance thought to lubricate the nipple. The breasts change in size and nodularity in response to cyclic ovarian changes throughout reproductive life. Increasing levels of both estrogen and progesterone in the 3 to 4 days before menstruation increase vascularity of the breasts, induce growth of the ducts and acini, and promote water retention. As a result, breast swelling, tenderness, and discomfort are common symptoms just before the onset of menstruation. After menstruation, cellular proliferation begins to regress, acini begin to decrease in size, and retained water is lost. In time, after repeated hormonal stimulation, small persistent areas of nodulations may develop just before and during menstruation, when the breast is most active. The physiologic alterations in breast size and activity reach their minimal level approximately 5 to 7 days after menstruation stops. The best time for a woman who wishes to perform a breast self-examination (BSE) is during this phase of the menstrual cycle or whenever the breasts are not tender or swollen (see Patient Instructions for Self-Management box). Initially, menstrual periods are irregular, unpredictable, painless, and anovulatory. After the ovary produces adequate cyclic estrogen to make a mature ovum, periods tend to be regular and ovulatory. The menstrual cycle is a complex interplay of events that occur simultaneously in the endometrium, hypothalamus and pituitary glands, and ovaries. The menstrual cycle prepares the uterus for pregnancy. When pregnancy does not occur, menstruation follows. Menstruation is the periodic uterine bleeding that begins approximately 14 days after ovulation. The average length of a menstrual cycle is 28 days, but variations are common. The first day of bleeding is designated as day 1 of the menstrual cycle, or menses (Fig. 2-7). The average duration of menstrual flow is 5 days (range of 1 to 8 days), and the average blood loss is 50 ml (range of 20 to 80 ml), but these vary greatly (Fehring, Schneider, & Raviele, 2006). The woman’s age, physical and emotional status, and environment also influence the regularity of her menstrual cycles. Toward the end of the normal menstrual cycle, blood levels of estrogen and progesterone fall. Low blood levels of these ovarian hormones stimulate the hypothalamus to secrete gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). In turn, GnRH stimulates anterior pituitary secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) that stimulates development of ovarian graafian follicles and their production of estrogen. Estrogen levels begin to fall, and hypothalamic GnRH triggers the anterior pituitary release of luteinizing hormone (LH). A marked surge of LH and a smaller peak of estrogen (day 12; see Fig. 2-7) precede the expulsion of the ovum (ovulation) from the graafian follicle by approximately 24 to 36 hours. LH peaks at approximately the thirteenth or fourteenth day of a 28-day cycle. If fertilization and implantation of the ovum do not occur by this time, the corpus luteum regresses. Levels of progesterone and estrogen decline, menstruation occurs, and the hypothalamus is once again stimulated to secrete GnRH. This process is the hypothalamic-pituitary cycle. The primitive graafian follicles contain immature oocytes (primordial ova). Before ovulation, from 1 to 30 follicles begin to mature in each ovary under the influence of FSH and estrogen. The preovulatory surge of LH affects a selected follicle. The oocyte matures, ovulation occurs, and the empty follicle begins its transformation into the corpus luteum. This follicular phase (preovulatory phase) (see Fig. 2-7) of the ovarian cycle varies in length from woman to woman and accounts for almost all variations in ovarian cycle length (Fehring et al., 2006). On rare occasions (approximately 1 in 100 menstrual cycles), more than one follicle is selected and more than one oocyte matures and undergoes ovulation. The endometrial cycle is divided into four phases (see Fig. 2-7). During the menstrual phase, shedding of the functional two thirds of the endometrium (the compact and spongy layers) is initiated by periodic vasoconstriction in the upper layers of the endometrium. The basal layer is always retained, and regeneration begins near the end of the cycle from cells derived from the remaining glandular remnants or stromal cells in the basalis. Implantation of the fertilized ovum generally occurs approximately 7 to 10 days after ovulation. If fertilization and implantation do not occur, the corpus luteum, which secretes estrogen and progesterone, regresses. With the rapid fall in progesterone and estrogen levels, the spiral arteries go into spasm. During the ischemic phase, the blood supply to the functional endometrium is blocked, and necrosis develops. The functional layer separates from the basal layer, and menstrual bleeding begins, marking day 1 of the next cycle (see Fig. 2-7). The climacteric is a transitional phase during which ovarian function and hormone production decline. This phase spans the years from the onset of premenopausal ovarian decline to the postmenopausal time when symptoms stop. Menopause refers to the last menstrual period. Unlike menarche, however, menopause can be dated only with certainty 1 year after menstruation ceases. The average age at natural menopause is 51 to 52 years, with an age range of 35 to 60 years. Menopause is preceded by a period known as the perimenopause, during which ovarian function declines. Ova slowly diminish, and menstrual cycles are anovulatory, resulting in irregular bleeding; the ovary stops producing estrogen, and eventually menses no longer occurs. This period lasts approximately 5 years (range 2-8 years) (Speroff & Fritz, 2005). The sexual response cycle is divided into four phases: excitement phase, plateau phase, orgasmic phase, and resolution phase. The four phases occur progressively, with no sharp dividing line between any two phases. Specific body changes take place in sequence. The time, intensity, and duration for cyclic completion also vary for individuals and situations. Table 2-1 compares male and female body changes during each of the four phases of the sexual response cycle. TABLE 2-1 Four Phases of Sexual Response Preconception health promotion provides women and their partners with information that is needed to make decisions about their reproductive future. Preconception counseling guides couples on how to prevent unintended pregnancies, stresses risk management, and identifies healthy behaviors that promote the well-being of the woman and her potential fetus (Moos, 2006). All providers who treat women for well-woman care or other routine care should incorporate preconception health screening as part of the routine care for women of reproductive age (Johnson et al., 2006). The initiation of activities that promote healthy mothers and babies must occur before the period of critical fetal organ development, which is between 17 and 56 days after fertilization. By the end of the eighth week after conception and certainly by the end of the first trimester, any major structural anomalies in the fetus are already present. Because many women do not realize that they are pregnant and do not seek prenatal care until well into the first trimester, the rapidly growing fetus may be exposed to many types of intrauterine environmental hazards during this most vulnerable developmental phase. Preconception care is important for women who have had a problem with a previous pregnancy (e.g., miscarriage, preterm birth). Although causes are not always identifiable, in many cases, problems can be identified and treated and may not recur in subsequent pregnancies. Preconception care is also important to minimize fetal malformations. For example, the woman may be exposed to teratogenic agents such as drugs, viruses, and chemicals, or she may have a genetically inherited disease. Preconception counseling can educate the woman about the effects of these agents and diseases, which can help prevent harm to the fetus or allow the woman to make an informed decision about her willingness to accept potential hazards should a pregnancy occur (Atrash, Johnson, Adams, Cordero, & Howse, 2006). A model for preconception care of women of reproductive age targets all women from menarche to menopause at every encounter, not just in maternity and women’s health. Providing optimal health care for women whether or not they desire to conceive can result in a high level of preconception wellness (Moos, 2006). Suggested components of preconception care, such as health promotion, risk assessment, and interventions, are outlined in Box 2-1. Almost half of the pregnancies in the United States each year are unintended even with birth control use (Trussell, 2007). Education is the key to encouraging women to make family planning choices based on preference and actual risk-to-benefit ratios. Women who enter the health care system seeking contraceptive counseling can be assisted to use a chosen method correctly (see Chapter 4 for further discussion). Women also enter the health care system because of their desire to achieve a pregnancy. Approximately 15% of couples in the United States have some degree of infertility. Infertility can cause emotional pain for many couples, and the inability to produce an offspring sometimes results in feelings of failure and inordinate stress on the relationship. Steps toward prevention of infertility should be undertaken as part of ongoing routine health care, and such information is especially appropriate in preconception counseling. For additional information about infertility, see Chapter 4. Irregularities or problems with the menstrual period are among the most common concerns of women and often cause them to seek help within the health care system. Common menstrual disorders include amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, endometriosis, and menorrhagia or metrorrhagia. These problems are discussed in Chapter 3. The United States spends more on health care than any other industrialized nation, yet major problems still exist. In the United States, disparity among races and socioeconomic classes affects many facets of life, including health. Limited money and awareness can lead to a lack of access to care, delay in seeking care, few prevention activities, and little accurate information about health and the health care system. Women use health services more often than do men but are more likely than men to have difficulty in financing the services. They are twice as often underinsured (i.e., they have limited coverage with high-cost co-payments or deductibles). Eighteen percent of women have no health insurance (National Women’s Law Center, 2007). Insurance coverage varies significantly by age, marital status, race, and ethnicity. Caucasians of all ages are more likely than African-Americans, Hispanics, and other racial or ethnic groups to have private insurance (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005). Single, separated, or divorced individuals are less likely to have insurance. Often, unmarried teenagers, who are usually covered by their parents’ medical insurance, do not have maternity coverage because policies have inclusion statements that cover only the employee or spouse. More than twice as many women as men are insured by Medicaid (Patchias & Waxman, 2007). In most states, Medicaid includes special benefits for pregnant women, but they are limited to treatment of pregnancy-related conditions and terminated 60 days after the birth. Midwifery care has helped contain some health care costs, but reimbursement issues still exist in some areas.

Assessment and Health Promotion

Web Resources

![]()

Female Reproductive System

External Structures

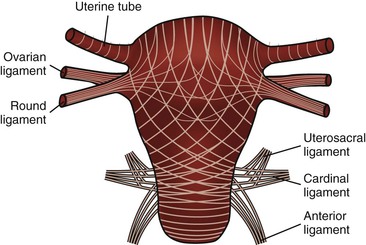

Internal Structures

Bony Pelvis

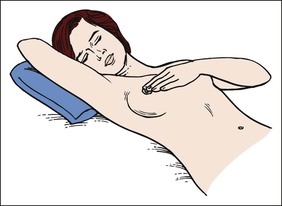

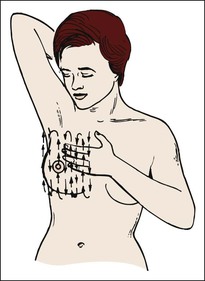

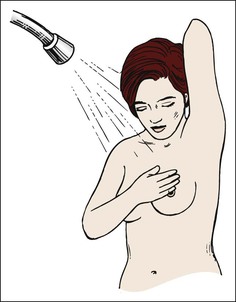

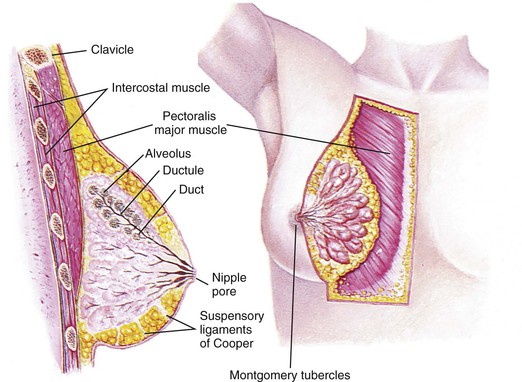

Breasts

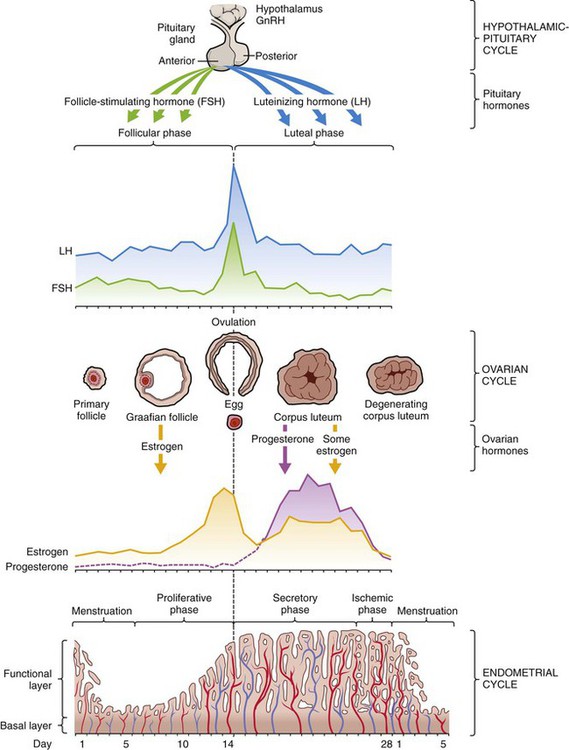

Menstruation

Menstrual cycle

Hypothalamic-pituitary cycle.

Ovarian cycle.

Endometrial cycle.

Climacteric.

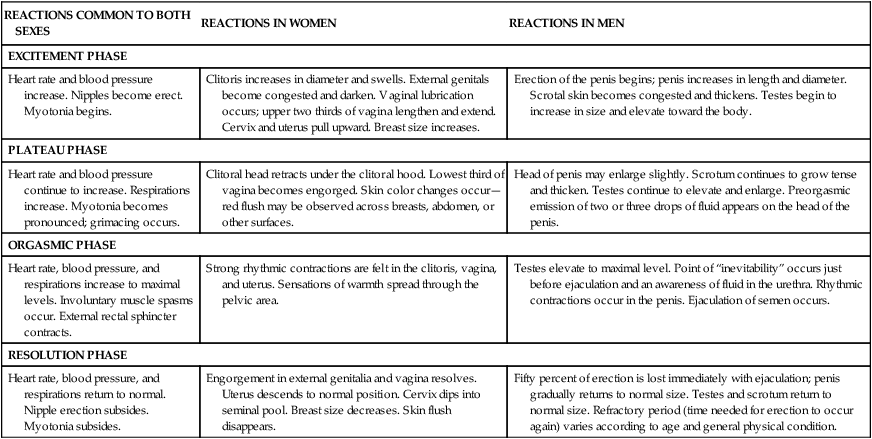

Sexual Response

REACTIONS COMMON TO BOTH SEXES

REACTIONS IN WOMEN

REACTIONS IN MEN

EXCITEMENT PHASE

Heart rate and blood pressure increase. Nipples become erect. Myotonia begins.

Clitoris increases in diameter and swells. External genitals become congested and darken. Vaginal lubrication occurs; upper two thirds of vagina lengthen and extend. Cervix and uterus pull upward. Breast size increases.

Erection of the penis begins; penis increases in length and diameter. Scrotal skin becomes congested and thickens. Testes begin to increase in size and elevate toward the body.

PLATEAU PHASE

Heart rate and blood pressure continue to increase. Respirations increase. Myotonia becomes pronounced; grimacing occurs.

Clitoral head retracts under the clitoral hood. Lowest third of vagina becomes engorged. Skin color changes occur—red flush may be observed across breasts, abdomen, or other surfaces.

Head of penis may enlarge slightly. Scrotum continues to grow tense and thicken. Testes continue to elevate and enlarge. Preorgasmic emission of two or three drops of fluid appears on the head of the penis.

ORGASMIC PHASE

Heart rate, blood pressure, and respirations increase to maximal levels. Involuntary muscle spasms occur. External rectal sphincter contracts.

Strong rhythmic contractions are felt in the clitoris, vagina, and uterus. Sensations of warmth spread through the pelvic area.

Testes elevate to maximal level. Point of “inevitability” occurs just before ejaculation and an awareness of fluid in the urethra. Rhythmic contractions occur in the penis. Ejaculation of semen occurs.

RESOLUTION PHASE

Heart rate, blood pressure, and respirations return to normal. Nipple erection subsides. Myotonia subsides.

Engorgement in external genitalia and vagina resolves. Uterus descends to normal position. Cervix dips into seminal pool. Breast size decreases. Skin flush disappears.

Fifty percent of erection is lost immediately with ejaculation; penis gradually returns to normal size. Testes and scrotum return to normal size. Refractory period (time needed for erection to occur again) varies according to age and general physical condition.

Reasons for Entering the Health Care System

Preconception Counseling

Fertility Control and Infertility

Menstrual Problems

Barriers to Seeking Health Care

Financial Issues

Assessment and Health Promotion

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access