Chapter 18 Assessing health needs

Overview

The first phase in health promotion planning is an assessment of what a client or population group needs to enable them to become healthier. Health care usually takes the individual as its starting point. Public health concerns the health and welfare of people in groups. Practitioners do not assess individuals in isolation from the communities in which they live. As we have seen in previous chapters the health experiences of individuals are affected by where they reside. The local knowledge of practitioners about the range of local services, facilities and networks is an important part of needs assessment. Within a neighbourhood there will be people in settings such as schools and workplaces and population groups with specific health needs. Practitioners need to know how to assess individuals, how to manage their care and how to encourage healthier lifestyles. They also require an understanding of people’s ways of life and the health problems and opportunities they experience and they need to know how to use this understanding to assess the needs of people in groups systematically. The term needs assessment describes the process of gathering information. It has been defined as a ‘systematic method of reviewing the health needs and issues facing a given population leading to agreed priorities and resource allocation that will improve health and reduce inequalities’ (Cavanagh & Chadwick 2005). The purpose of health needs assessment at national, regional or local level is twofold:

Recognition of the right to participate in defining health needs and health care was acknowledged in the 1978 World Health Organization (WHO) Alma Ata Declaration, and one of the underlying principles of Health For All is community participation (WHO 1985).

National Health Service (NHS) reforms have emphasized the participation of local people in setting priorities, signalling a philosophical shift from a paternalistic medical model to a participatory consumer-led model. This chapter considers the ways in which local health needs are assessed and applied in planning for health promotion. It should be read in conjunction with Chapter 3, which outlines the principal sources of information about health status.

Defining health needs

There are two different understandings of what constitutes a health need. It can be seen as:

Economists tend to avoid the use of the term needs altogether, arguing that it is overlaid with emotion and what is really meant by a health need is actually a matter of people’s wants and demands, and these are limitless (Cohen 2008). Identifying health needs is therefore a question of identifying priorities.

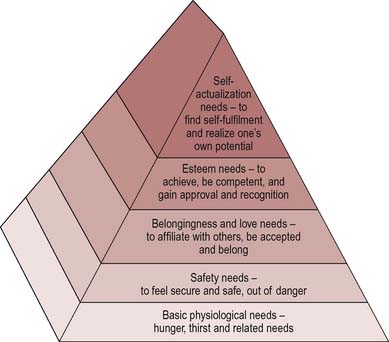

An alternative view is that there are universal needs. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow 1954) suggests that all human needs are in fact health needs (Figure 18.1).

For a person to be self-actualizing, physical, social and emotional needs must be met. Doyal & Gough (1992) have similarly argued that the ultimate goal of human beings is to participate fully in society and to do this the basic needs for physical health and for autonomy must be met. These needs are not relative to a particular country or period of time but are fundamental rights and include the prerequisites for health – peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice and equity (WHO 1986). But these needs are not undisputed. How healthy do people have to be before we can say that their needs have been met? Bradshaw (1972), in a widely used taxonomy, distinguished four types of health and social need:

Normative needs

Normative needs are objective needs as defined by professionals, who also identify the ways in which these needs can be met. A normative need reflects a professional judgement that a person or persons deviate from a required standard. This may be against some external criteria such as occupational or legal requirements. Thus the manager of a restaurant is in need of training because she has not completed a course in food hygiene. Or it may be that a person deviates from what is defined by medical staff as the range of ‘clinically normal’ physiological indicators.

Felt needs

Felt needs are what people really want. They are needs identified by clients themselves which may relate to services, information or support which can be termed service needs. Moves towards bottom-up approaches in health and social care have meant a greater acceptance of service users’ views. (Chapter 6 in our companion volume (Naidoo & Wills 2005) discusses some of the policy drivers to patient and public involvement.) Needs may be limited by the perceptions of an individual. Individuals may not believe themselves to be in need simply because they do not know what is available in terms of treatment or services.

Expressed need

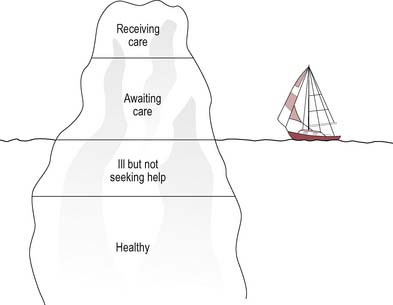

Expressed need arises from felt needs but is expressed in words or action – it has become a demand. Thus clients or groups are expressing a need when they ask for help or information, or when they make use of a service. Expressed need is often used to measure the adequacy of service provision, even though it is not a comprehensive or complete measure. There are also objective needs which exist but are not expressed. Only a proportion of patients make contact with health services and they are merely the tip of an iceberg of potential need, as illustrated in Figure 18.2.

Sometimes people will use a service because it is all that is available, even if it does not adequately meet needs. The best example of expressed need (and unmet demand) is the waiting list. Some needs are not expressed, perhaps because of an inability or unwillingness to articulate the need. This could be due to language difficulties or a lack of knowledge. Expressed needs should not be taken as an indicator of demand because they also exclude needs which are felt but not expressed. Tudor Hart’s inverse-care law has been of vital importance in showing that just because a service or treatment is used less does not mean that it is needed less (Tudor Hart 1971). Those who could most benefit from a service are often those least likely to use it. People may express different needs, and there is a tendency to listen to those with loud and powerful voices, such as views which come from an established group or views which appear to express a popular need. Responding to expressed needs may also therefore have the effect of increasing inequalities in service provision.

Comparative needs

Bradshaw’s work (1994) is useful in showing that different groups in society hold different definitions of need. We can see that needs are not objective and observable entities to which we must just match our interventions. The concept of need is a relative one and is influenced both by values and attitudes and by other agendas.

A very different list of needs may be compiled by pregnant women, including for example:

What is clear from the above discussion is that definitions of need vary depending on whose interpretation and values are used. People’s health needs are not the same as those of 20 years ago – the nature and prevalence of diseases may change, as do the expectations of the population and the capacity of health services to meet them. The NHS uses the term health gain in association with health needs to signal that the meeting of needs is related to a person’s ability to benefit. Health gain is defined as:

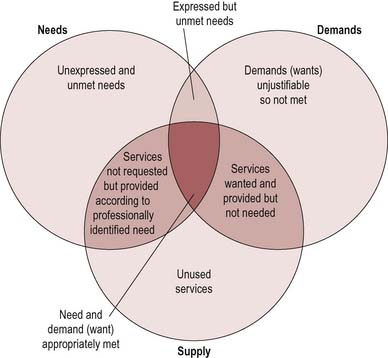

The concept of health gain is rooted in a medical model which sees health as the absence of disease. Consequently, health needs tend to be defined as problems which may be successfully met by services or treatment. Because need is seen as infinite and resources as limited, health authorities confine themselves to what is known to be effective care. Yet community surveys often show that the public define ill health far more broadly than simply problems requiring treatment by health services. Many priorities for health go beyond the narrow outcomes encompassed by adding ‘years to life’ and require health authorities to take account of the structural influences on health, such as housing, community safety and transport links. The meeting of needs is also related to what can be offered (what the state can supply). These differing interpretations are illustrated in Figure 18.3.

The purpose of assessing health needs

The process of assessing needs is nothing new. As we shall see in the next chapter, understanding needs is integral to a basic process approach to planning. Needs assessment including the collection of data is the first step, from which subsequent aims will be derived. Assessing the health and social needs of local populations is a means of obtaining accurate and appropriate information on which to base priorities and ensures that decisions are based on solid information and evidence. This overall purpose can be broken down into different stages as follows.

BOX 18.1

BOX 18.1 BOX 18.2

BOX 18.2

BOX 18.3

BOX 18.3 BOX 18.4

BOX 18.4

BOX 18.5

BOX 18.5