lower-extremity arterial disease, and diabetic neuropathy. To obtain a patient’s history, follow these steps:

[check mark] Review the patient’s medical history, which details allergies, laboratory studies, radiologic studies, vascular studies, medications, past illnesses, surgical procedures, and other pertinent facts related to the patient’s illnesses and problems. Ask about allergies to foods or medications, including topical skin and wound care products. Also, ask the patient if his skin’s appearance changes with the seasons. |

[check mark] Review the patient’s family history, paying particular attention to the history of parents, siblings, grandparents, and natural children, and detailing the age and general health of living relatives, the death and cause of death of all deceased family members, and any chronic diseases that occur in the immediate family. This information will alert you to the presence of inherited or congenital conditions or diseases. |

[check mark] Review the patient’s social history, including age-appropriate information regarding past and current activities, such as marital status, living arrangements, current employment and occupational history, sexual history, level of education, and use of drugs, alcohol, or tobacco. Ask about other social factors that may influence the patient’s activities of daily living. |

[check mark] Ask about the patient’s bathing routines and about the different soaps, shampoos, conditioners, lotions, oils, and other topical products he uses routinely. Any such products may lead to changes in skin, appearing as xerosis, pruritus, wounds, rashes, or a change in skin color. |

[check mark] Obtain a list of past and current medications and dressings, including all medications and dressings that have been used, have been effective, or have failed. |

[check mark] Review previous treatments, dressings, drugs, and adjunctive modalities (such as physical therapy, skin replacements, and growth factors) and determine their effectiveness. |

[check mark] Review all laboratory, radiology, and vascular studies that have been performed. |

[check mark] Review the patient’s nutritional status and supportive therapies. For the patient who has a wound, obtain the following information: |

[check mark] Review all clinician consultations related to specialty management programs for skin and wound care. |

[check mark] Review (if indicated) all support surfaces and positioning devices used to manage the patient’s tissue load. |

[check mark] Review (if indicated) any use of devices, such as compression stockings, custom shoes or braces, and assistive devices. |

[check mark] Assess the patient’s knowledge of the disease, and document all factors that affect learning needs. |

When did the skin condition or wound occur?

Who has taken care of the skin condition or wound?

What strategies have been used to facilitate healing of the skin condition or wound?

What documented findings (e.g., written information, laboratory test results, and vascular or radiology test results) can be reviewed to support the care of the skin condition or wound?

[check mark] Location. Anatomic location describes the lesion and the nearest bony prominence or another anatomic landmark. Detailing the wound’s location is imperative for accurate documentation and consistent care by each provider working with the patient. |

[check mark] Size (length, width, depth, undermining). Accurate wound measurements can assist the clinician in designing an appropriate care plan. Size includes length, width, and depth. Consistent vocabulary and units of measure are essential when documenting or describing the wound. (See Measuring wound depth, page 20.) |

Color and type of wound tissue. Wound bed description and wound color provide a consistent approach in defining the tissue in the base of the wound. Descriptors such as granulation tissue, slough, and eschar are typically used to define tissue type. Tissue color also has been used to distinguish viable from nonviable tissue and is another descriptor that assists in the management process. |

[check mark] Exudate or drainage amount and type. The amount of wound exudate or drainage is assessed and described with each dressing change. The number of dressingchanges needed per week can help in estimating the amount of exudate present. Large amounts of exudate may indicate an infection and a barrier to healing. |

[check mark] Odor. Odor helps define the presence and type of bacteria in the wound and is assessed only after the clinician has cleaned the wound. |

[check mark] Periwound skin condition. Periwound skin is assessed for color and temperature. Inflammation or erythema may indicate wound infection or dermatitis. Assessing the periwound skin for maceration or denuded tissue is also important. Macerated periwound skin should prompt the clinician to assess the topical wound dressing for its ability to manage exudate. Macerated or denuded periwound skin is also a concern when the clinician needs to anchor a dressing. |

[check mark] Wound margins. The condition of the wound margins can provide the clinician with information about the wound’s chronicity or healing ability. Newly formed epithelium along the wound edge, commonly flat and pale pink to lavender in color (termed the edge effect), indicates stimulated healing. |

[check mark] Pain. The presence, absence, or type of pain may indicate infection, underlying tissue destruction, neuropathy, or vascular insufficiency. |

[check mark] Adjunctive therapies. Adjunctive therapies and support—such as negative-pressure wound therapy, support surfaces for bed and chair, and rehabilitation services—play a vital role. The patient’s wound should define the level of therapy needed. |

[check mark] Patient knowledge of the disease and wound management. The educational needs of the patient must be evaluated on an individual basis, beginning with the nonjudgmental assessment of the patient’s knowledge relevant to the care plan. An experienced clinician should direct the educational activities. |

[check mark] Dressing management. A moist wound-healing environment requires a proper dressing. Considerations for choosing proper primary and secondary dressings are based on wound characteristics, including size, undermining or tunneling, and amount of exudate. (See Measuring wound tunneling, page 21.) |

Bulla | ▪ A vesicle larger than 5 mm in diameter |

Cyst | ▪ An elevated, circumscribed area of the skin filled with liquid or semisolid fluid |

Macule | ▪ A flat, circumscribed area ▪ Brown, red, white, or tan in color |

Nodule | ▪ An elevated, firm, circumscribed, and palpable area ▪ Can involve all layers of the skin ▪ Larger than 5 mm in diameter |

Papule | ▪ An elevated, palpable, firm, circumscribed lesion ▪ Generally less than 5 mm in diameter |

Plaque | ▪ An elevated, flat-topped, firm, rough, superficial papule ▪ Larger than 2 cm in diameter (papules can coalesce to form plaques) |

Pustule | ▪ An elevated, superficial area that’s similar to a vesicle but filled with pus |

Vesicle | ▪ An elevated, circumscribed, superficial, fluid-filled blister ▪ Less than 5 mm in diameter |

Wheal | ▪ An elevated, irregularly shaped area of cutaneous edema ▪ Solid, transient, and changing, with a variable diameter ▪ Red, pale pink, or white in color |

Crust | ▪ Slightly elevated ▪ Variable size ▪ Consists of dried serum, blood, or purulent exudate |

Excoriation | ▪ Linear scratches on the skin, which may or may not be denuded |

Lichenification | ▪ Rough, thickened epidermis ▪ Accentuated skin markings caused by rubbing or scratching (e.g., chronic eczema, lichen simplex) |

Scale | ▪ Heaped-up keratinized cells ▪ Flaky exfoliation ▪ Irregular ▪ Thick or thin, dry or oily ▪ Variable size ▪ Silver, white, or tan in color |

condition of the skin around the wound

status of the wound (whether acute or chronic)

amount of wound exudate, if any

presence or absence of necrosis

appearance of the wound, such as whether it is red, yellow, or black

evidence of possible infection or lack thereof

degree of cleaning and packing required

nature of the dressings needed

management of the drainage.

top of the patella, and a mathematical formula is then used to determine the patient’s height.

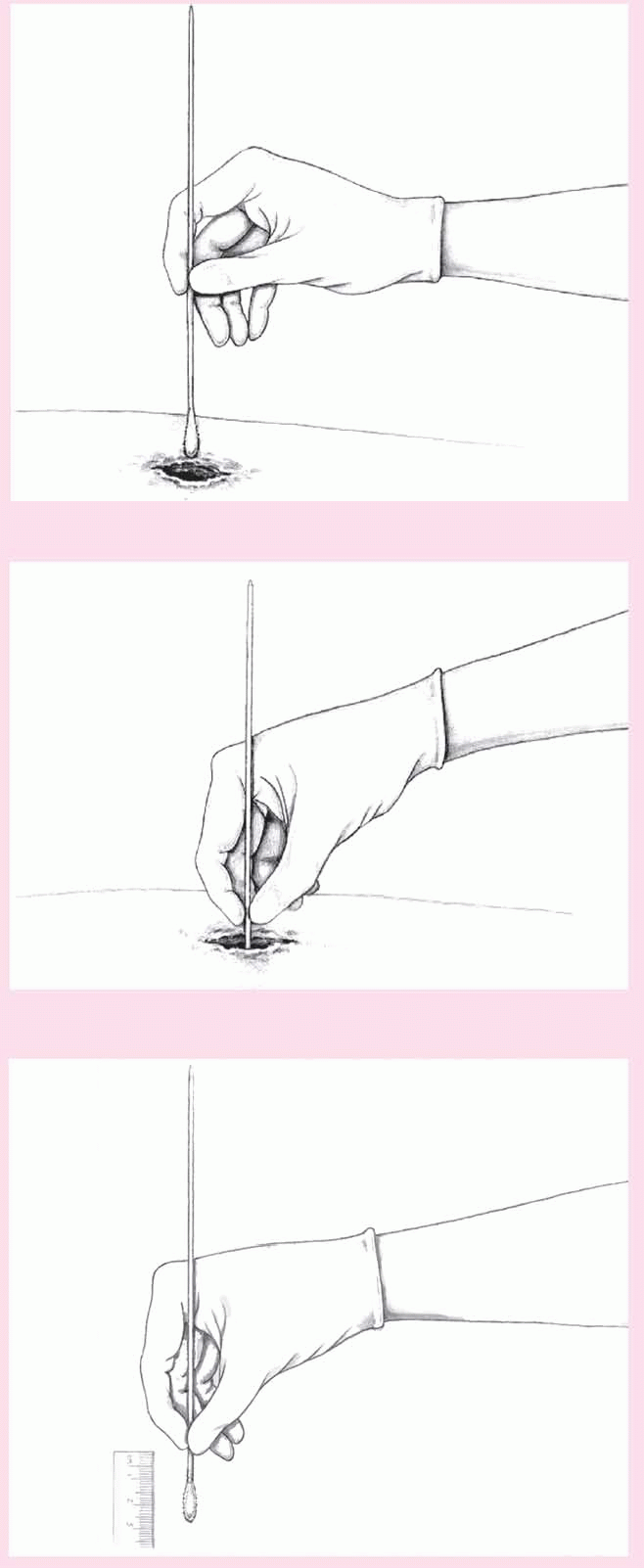

Put on gloves and gently insert the applicator into the sites where tunneling occurs.

View the direction of the applicator as if it were a hand of a clock (12 o’clock points in the direction of the patient’s head).

Progressing in a clockwise direction, document the deepest sites where the wound tunnels (e.g., 3 o’clock).

Insert the applicator into the tunneling areas.

Grasp the applicator where it meets the wound’s edge.

Pull the applicator out, place it next to a measuring guide, and document the measurement (in centimeters).

Markers of malnutrition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree