Chapter 7. Asking Research Questions

Ian Atkinson

▪ Introduction

▪ Developing a research question

▪ Choosing a topic

▪ Formulating the research question

▪ Conclusion

Developing a research question

Developing a clear research question is key to the development of any research investigation and is needed for a variety of other reasons. It is unlikely that providers of research funds would wish to spend substantial sums of money on projects which set out to conduct some vague and unspecified exploration. We need to know from the beginning what we want to find out even though in some studies this may evolve in the course of the investigation.

Once a research question is clarified then a study design and methods will evolve from it. In other words, once the research question is fixed then so are the choices of design and methods which can be employed to obtain the data to answer the question. If this is accepted then we must also accept that arguments over which research approach is the better, i.e. quantitative or qualitative, are of little value. If we ask a qualitative research question then we are left with little alternative but to employ qualitative methods. If we ask a quantitative research question then equally we must employ quantitative research methods (Sackett and Wennberg 1997). Although this should not be taken to mean that both types of question and both types of methods could not be part of the same piece of research.

There is little doubt that nursing and health care in general provide an extraordinary source of the most interesting questions for research. No matter what background a researcher may have, be it from management science to geography or from chemistry to social anthropology, nursing and health care will be able to pose valuable questions which require such a range of disciplines to provide answers.

In the selection of subjects for research we follow a process of narrowing an initial broad area to a refined topic, followed by a specific research question and finally deciding upon precisely what information we need in order to answer that question. Selecting a broad area in which to conduct research will rarely pose any great difficulty and may be determined simply by personal knowledge, experiences and interests, or indeed those of colleagues and other associates. The availability of research funding obviously plays a key role in determining research areas but the requirements of funding bodies rarely play a significant role in undergraduate and Masters level research projects. Research areas are by definition very broad, for example a diagnosis such as stroke, or a particular aspect of care such as nurse patient communication. In themselves these present such wide areas that they must be first narrowed down to a specific topic before we can begin to start developing a research question.

Choosing a topic

A narrow topic for research will generally be derived from a number of considerations. A range of different factors are likely to influence and direct the choice of topic. An awareness of material already published in the area is going to be of key importance. The types of publication which should be of interest will include not only academic papers but outputs from government, the mass media, and the internal publications of various public and private organisations. Discussion among colleagues with interests and experience in the area can be invaluable. Conferences and study days provide ideal opportunities to meet and discuss ideas. In the case of student research, supervisors are generally consulted at an early stage of topic selection and often take a major role in narrowing the research topic.

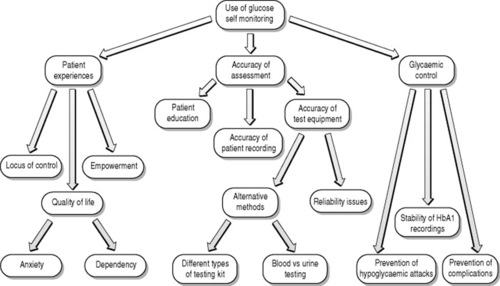

At this stage the topic may still be too broad for a focused research question to have emerged. A variety of methods are available for analysing a broad topic which may help to identify a specific topic for research. One of these is the construction of relevance trees and this can be usefully applied here (Futures Group 1994). The approach is simple in principle and is likely to lead to new insights and a clear understanding of a topic. However, it does entail a good deal of effort and concentration by the user!

Construction of the relevance tree involves writing the topic at the head of a sheet of paper then breaking it down into components. Figure 7.1 gives an illustration using ‘blood glucose monitoring’ as an example topic. The root is labelled ‘Use of glucose self monitoring’ and this is broken down into three components. These are ‘patient experiences’, ‘accuracy of assessment’ and ‘glycaemic control’. Each of these components is further broken down into sub-components and so the process continues. This continual breaking down could continue ad infinitum and has to be limited in some way. Certain parts of the branching would soon become less interesting and those with more appealing topics would become the focus of attention. The tree in Figure 7.1 is quite limited in its breakdown of the topic but its purpose is only to illustrate the approach. The intricacies of the method are fully discussed in the (Futures Group paper (1994). Connections and overlaps between the different branches soon become apparent and these can be developed. In the example, issues of patient empowerment could be easily linked to the prevention of hypoglycaemic attacks. Extensive development of such a tree may eventually lead the user to ideas which otherwise would not have been identified. The method has to be used creatively to be of most value.

|

| Figure 7.1 Example of a relevance tree for identifying the components of a research topic. |

Formulating the research question

Now the research question should be in sight and can be formulated either as an interrogative question or as an hypothesis. Often confusion arises as to whether a study should use a research question or a hypothesis. As a general rule it is the more structured studies, for example experiments, which tend to use hypotheses while the less structured surveys and qualitative studies use interrogative questions (Punch 2005). Whether we choose to use either a question or a hypothesis it will not affect the type of data required and the logic of the design needed to provide an answer.

The interrogative research question just states what the research is trying to find out and is written as a question. For example, 1: ‘Does self monitoring of blood glucose lead to a change in the number of hypoglycaemic attacks experienced?’ Sometimes research questions are not quite so precisely stated but nevertheless still serve their purpose quite adequately. For example, 2: ‘What are the perceived benefits of self-monitoring of blood glucose among insulin-dependent patients?’

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree