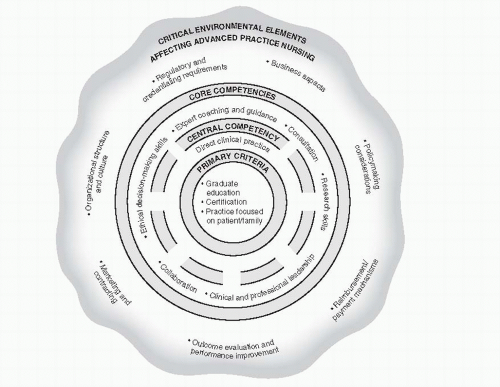

Although the six aforementioned core competencies underlie all APRN practice, they are by no means unique to APRNs. Basic-prepared nurses may also demonstrate them. What distinguishes these competencies from basic-prepared nursing is that they are essential to (i.e., required for) APRN practice. In other words, if an APRN

is not proficient in or does not consistently strive to demonstrate all of these competencies in his or her practice, he or she is technically

not providing advanced practice nursing care. The expectation is that these six competencies are consistently demonstrated in the APRN’s routine practice. As such, these competencies serve as an excellent framework for discussing the role of the APRN in chronic illness care.

Expert Coaching and Guidance

Coaching and guidance are essential to the provision of chronic illness care. On the surface, this competency seems straightforward and the experienced nurse may assume he or she does this well and with “expertise.” It is easy to assume proficiency with this competency; most nurses interact with and teach patients frequently during their daily patient care activities. Upon closer examination, there is more to coaching and guidance than meets the eye.

Spross (2009) reminds us that the verb “coach” stems from the word’s origins as a carriage used to facilitate the safe transmission of individual(s) from one point to another. Transferring this to nursing practice, coaching is “interpersonal work that helps people who are facing personal transitions or

journeys” (p. 161), such as those associated with chronic illnesses.

The phenomenon of expert coaching is complex. In addition to establishing rapport, actively listening, and expressing empathy, expert APRN coaching requires clinical competence, and creative problem solving, as well as knowledge and skill regarding how best to assist individuals who are experiencing crisis, desiring change, or even expressing apathy toward an illness or situation. For example, to assist a middleaged adult female with obesity and poorly controlled type II diabetes who desires to lose weight and bring her glycosolated hemoglobin level (HgbA1c) to goal range, the APRN must demonstrate expertise regarding the pathophysiology of diabetes and the complications associated with poor control. He or she must also be thoroughly familiar with current evidence regarding diabetes care parameters and treatments. In addition, the APRN should possess knowledge of and experience with efficacious diabetes education strategies, as well as the transtheoretical stages of change model (

DiClemente & Prochaska, 1982;

Norcross, Krebs, & Prochaska, 2011;

Prochaska, 1979), motivational interviewing (

Miller & Rollnick, 1992;

Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2007), and other evidencebased behavioral change techniques.

Clinical Competence

To provide expert coaching and guidance in chronic illness care, APRNs must be knowledgeable regarding the illness(es) of interest and experienced enough to anticipate the informational and emotional needs of the patient and his or her family members. Going beyond asking the patient and family what they “want to know” and anticipating what they “need to know” is a critical aspect of the APRN’s coaching skills and requires that the APRN be intimately familiar with the illness of interest, its progression, and its management.

Creative Problem Solving

Just as no one asks to have a chronic illness, no one asks to have the myriad problems that are often associated with chronic illness. Expert coaching in chronic illness care often involves assisting patients and families who may be angry, despondent, anxious, confused, or desperate. Thus, it is critical that the APRN be willing to set aside his or her routine “script” or “protocol” and be able to create a revised plan that takes into consideration the unique needs, styles, and interests of the patient or family. Examples of creative educational and coaching strategies for chronic illness management that are gaining support in the research literature are group appointments for diabetes mellitus (

Edelman et al., 2010); the use of lay-leaders for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, arthritis, and chronic pain (

Foster, Taylor, Eldridge, Ramsay, & Griffiths, 2009); and the use of mobile phone technology for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension (

Yoo et al., 2009).

Consultation

Although the APRN will often consult with other APRNs and members of the healthcare team, an essential feature of the role is that APRNs also serve as consultants to other professionals (e.g., nurses, physicians, mental health providers). There are a number of ways in which consultation may be categorized; however, in chronic illness care APRNs primarily provide consultations related to direct patient care. They either see a patient or make specific recommendations to the consultee (i.e., basic-prepared nurse, team of nurses, or

nonnursing provider) on how best to proceed with the patient’s care, or they assist the consultee with formulating an effective plan of care. Regardless of whether the APRN sees the actual patient or not, the aim of APRN-directed consultation is to assist the consultee in providing patient care.

Acting as a consultant requires that the APRN have expertise in a particular area and be respected for this expertise.

Barron and White (2009, p. 196) pose seven principles of professional APRN consultation that espouse the collaborative, professional, and transparent nature of APRN consultation:

The consultation is usually initiated by the consultee.

The relationship between the consultant and consultee is nonhierarchical and collaborative.

The consultant always considers contextual factors when responding to the request for consultation.

The consultant has no direct authority for managing patient care.

The consultant does not prescribe but rather makes recommendations.

The consultee is free to accept or reject the recommendations of the consultant.

The consultation should be documented.

Research

Gone are the days when APRNs can avoid “research” by choosing to work in clinical practice settings. For more than half a century, nurses have worked to base their care in research-based evidence. Now with the accessibility of current and comprehensive electronic research databases (e.g., Cummulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL] and the National Library of Medicine [through PubMed]), the ability to truly bridge the research-practice gap is no longer an impossible dream.

In most healthcare settings since 2000, the term

research has been replaced by the term

evidence, and evidence-based practice (EBP) has become a priority goal of all allied health professionals, including APRNs. EBP is most commonly defined as the integration of three components: 1) best research evidence, 2) clinician expertise, and 3) patient preferences and values (

Strauss, Richardson, Glasziou, & Haynes, 2005;

Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2010). To date, the EBP literature has primarily focused on how to develop compelling clinical questions, as well as how to search for and critique original research studies and systematic reviews. Very little has been published regarding how to best evaluate clinician expertise and patient values or how to “integrate” clinician expertise and values with research findings. Fortunately, APRNs have a long history of providing patient-centered care. Similarly, the development and recognition of nurse expertise has been well established and documented (e.g.,

Benner, 1984;

De Jong et al., 2010;

Foley, Kee, Minick, Harvey, & Jennings, 2002;

Gorman & Morris, 1991).

By definition, EBP does not elevate or promote the status of research evidence above clinician expertise or patient values. However, EBP does require a moderate degree of competency in basic statistics, research terminology, and research design, which unlike clinician expertise and patient values, are areas that are not as easily gained or mastered from experiential practice. Thus it is critical that APRNs value research, master basic research skills, and utilize these skills on a routine basis.

Depalma (2009) describes three sub-components to the research competency for APRNs. These skills are also echoed in the AACN’s

Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice (2006) and

Essentials of Master’s Education in Nursing (2011):

Interpretation and Use of Research Findings and Other Evidence in Clinical Decision Making

We live in exciting times, where a wealth of highquality research exists to help inform and guide ARPN practice. Although not every clinical scenario has been fully researched and a fresh set of unanswered questions arises from each new study, much of the work facing APRNs is supported by research. Indeed it is rare for the APRN, particularly the APRN working with individuals experiencing chronic illnesses, not to have relevant research to draw upon. Thus it is critical for APRNs to be able to competently search for and critically evaluate the research literature, especially as it applies to their own area of clinical expertise.

Having a mechanism to remain aware of current research findings is an all important first step toward competency in research. At present, a growing number of services exist to facilitate this. Some examples include daily electronic “Smart Briefs” from the American Nurses Association, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), and Physician’s First Watch. In addition, many other professional nursing organizations offer weekly or monthly electronic research updates to members.

Participation in professional journal clubs is another avenue for APRNs to remain current regarding the research literature and has the added benefit of being able to dialogue with others about research and how it applies to clinical practice. Professional journal clubs may be sponsored by a workplace organization or organized “off site” by a group of like-minded colleagues. They may occur in a variety of formats including face-to-face monthly meetings, email discussions, wikis, or blogs. Several professional organizations and journals are now hosting electronic journal clubs to subscribers, for example the

AANP Virtual Journal Club and the

Cochrane Journal Club. There are a number of excellent publications regarding the value of and how to initiate a professional journal club, and the interested reader is encouraged to review these (e.g.,

Deenadayalan, Grimmer-Somers, Prior, & Kumar, 2008;

Dobrzanska & Cromack, 2005;

Honey & Baker, 2011;

Hughes, 2010;

Lizarondo, Kumar, & Grimmer-Somers, 2010;

Luby, Riley, & Towne, 2006).

In addition to having access to research findings related to chronic illness, APRNs must also be able to critically evaluate these findings and determine whether and/or how the findings apply to practice. Simply put, critically appraising the research literature requires the ability to evaluate the validity of a single study’s methodology and the meaningfulness of its findings, while simultaneously synthesizing findings from multiple studies across the literature. Obviously, there is nothing “simple” about this process, and similar to many clinical skills, research appraisal is an acquired process that requires adequate education and experience. A variety of excellent courses, workshops, and websites exist to assist APRNs with developing the skills to be able to critically evaluate research evidence (see

Table 17-2). Having an EBP mentor or EBP team to consult

with and a supportive work environment are also invaluable to the successful acquisition of EBP skills (

Aitken et al., 2011;

Fineout-Overholt & Melnyk, 2010).

Similarly, APRNs’ practices should reflect an awareness of current research findings, which requires that they have and maintain mechanisms to remain current on the latest research literature. At present a variety of mechanisms exist to facilitate this, including daily or electronic research alerts from organizations such as the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners and Journal Watch (see

Table 17-3). Fortunately, a variety of possibilities are available including APRNs being able to dialogue with other professionals, as well as patients, regarding research evidence.

Evaluation of Practice

In addition to basing care on research-based evidence, APRNs who work with individuals

experiencing chronic illnesses should be routinely evaluating their clinical practice and practicerelated outcomes. These types of evaluations not only ensure quality but also provide data that can be used by researchers and stakeholders (i.e., consumers, insurers, healthcare agencies) who are studying or evaluating care provided by APRNs. Evaluation of APRN practice may revolve around any number of professional aspects including but not limited to scope and standards of practice, role and job descriptions, and evidence-based guidelines and national quality indicators (Depalma, 2009). For example, APRNs who work with adults and children experiencing diabetes could evaluate their own practices to ensure that they are supported by (i.e., contained within) national and state scopes and standards for practice. Similarly, these APRNs could also evaluate specific aspects of diabetes management for adherence rates (e.g., influenza vaccination, microalbuminuria, and retinopathy screening) and attainment of goal disease indicators (e.g., HgbA1c, blood pressure, and lipids).

Practice evaluations may occur using a variety of mechanisms. For example, checklists can be developed to compare national and state standards to a particular agency’s APRN job descriptions and evaluation criteria. Another example is conducting chart or electronic reviews of specific care practices (e.g., foot or retina evaluations in patients with diabetes) or patient outcomes (e.g., HgbA1c or lipid levels), which would need to be conducted in accordance with the

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA, 1996).

Regardless of how or what practice parameters are evaluated, it is essential that APRNs utilize evaluative data to improve their practices. Thus it is critical that the evaluative process be understood and supported by all participating providers (e.g., APRNs, basic-prepared nurses, technicians, and care providers). Similarly, it is important that data are reported in a clear, standardized fashion and that an established process for quality improvement/harm reduction be followed (e.g., using the principles of Continuous Quality Improvement [McLaughlin & Kaluzny, 2005] or Total Quality Management [Kelly, 2006]; see also

Carman et al., 2010).

Participation in Collaborative Research

In addition to being able to interpret and apply research findings and evaluate and improve care based on research-based evidence, APRNs should also be able to participate and collaborate in research activities related to their area of clinical expertise. Although APRNs do not need to design and oversee research studies, they should possess general knowledge about research paradigms and phases of the research process (

Burns & Grove, 2010;

Polit & Beck, 2006). Perhaps most importantly, APRNs need to be interested in research and earnestly desire to contribute to research knowledge by developing collaborative relationships with nurse scientists and others who are studying aspects of interest to APRN practice.