This section summarizes the basic principles and related concepts of the behaviorist, cognitive, social learning, psychodynamic, and humanistic learning theories. While reviewing each theory, readers are asked to consider the following questions:

Behaviorist Learning Theory

Focusing mainly on what is directly observable, behaviorists view learning as the product of the stimulus conditions (S) and the responses (R) that follow—sometimes termed the S-R model of learning. Whether dealing with animals or people, the learning process is relatively simple. Generally ignoring what goes on inside the individual—which, of course, is always difficult to ascertain—behaviorists closely observe responses and then manipulate the environment to bring about the intended change. Currently in educational and clinical psychology, behaviorist theories are more likely to be used in combination with other learning theories, especially cognitive theory (

Bush, 2006;

Dai & Sternberg, 2004). Behaviorist theory continues to be considered useful in nursing practice for the delivery of health care.

To modify people’s attitudes and responses, behaviorists either alter the stimulus conditions in the environment or change what happens after a response occurs. Motivation is explained as the desire to reduce some drive (drive reduction); hence, satisfied, complacent, or satiated individuals have little motivation to learn and change. Getting behavior to transfer from the initial learning situation to other settings is largely a matter of practice (strengthening habits). Transfer is aided by a similarity in the stimuli and responses in the learning situation and those encountered in future situations where the response is to be performed. Much of behaviorist learning is based on respondent conditioning and operant conditioning procedures.

Respondent conditioning (also termed

classical or

Pavlovian conditioning) emphasizes the importance of stimulus conditions and the associations formed in the learning process (

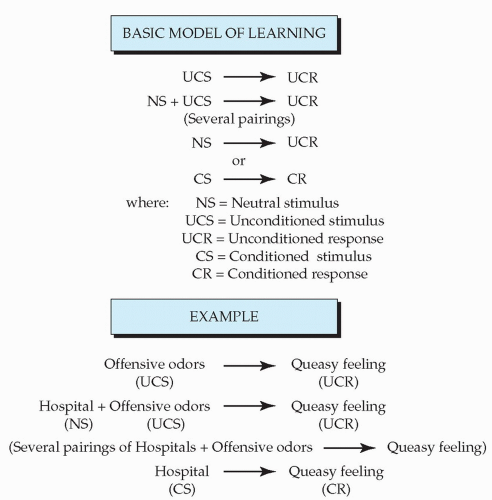

Ormrod, 2004). In this basic model of learning, a neutral stimulus (NS)—a stimulus that has no particular value or meaning to the learner—is paired with a naturally occurring unconditioned or unlearned stimulus (UCS) and unconditioned response (UCR) (

Figure 3-1). After a few such pairings, the neutral stimulus alone (i.e., without the unconditioned stimulus) elicits the same unconditioned response. Thus learning takes place when the newly conditioned stimulus (CS) becomes associated with the conditioned response (CR)—a process that may well occur without conscious thought or awareness.

Consider an example from health care. Someone without much experience with hospitals (NS) may visit a relative who is ill. While in the relative’s room, the visitor may smell offensive odors (UCS) and feel queasy and light-headed (UCR). After this initial visit and later repeated visits, hospitals (now the CS) may become associated with feeling anxious and nauseated (CR), especially if the visitor smells odors similar to those encountered during the first experience (see

Figure 3-1).

In health care, respondent conditioning highlights the importance of the healthcare facility’s atmosphere and its effects on staff morale. Often without thinking or reflection, patients and visitors formulate these associations as a result of their hospital experiences, providing the basis for long-lasting attitudes toward medicine, healthcare facilities, and health professionals.

In addition to influencing the acquisition of new responses to environmental stimuli, principles of respondent conditioning may be used to extinguish a previously learned response. Responses decrease if the presentation of the conditioned stimulus is not accompanied by the unconditioned stimulus over time. Thus, if the visitor who became dizzy in one hospital subsequently goes to other hospitals to see relatives or friends without smelling offensive odors, then her discomfort and anxiety about hospitals may lessen after several such experiences.

Systematic desensitization is a technique based on respondent conditioning that is used by psychologists to reduce fear and anxiety in their clients (

Wolpe, 1982). The assumption is that fear of a particular stimulus or situation is learned; thus it can also be unlearned or extinguished. With this approach, fearful individuals are first taught relaxation techniques. While they are in a state of relaxation, the fear-producing stimulus is gradually introduced at a nonthreatening level so that anxiety and emotions are not aroused. After repeated pairings of the stimulus under relaxed, nonfrightening conditions, the individual learns that no harm will come to him from the once fear-inducing stimulus. Finally, the client is able to confront the stimulus without being anxious and afraid.

In healthcare research, respondent conditioning has been used to extinguish chemotherapy patients’ anticipatory nausea and vomiting (

Lotfi-Jam et al., 2008;

Stockhurst, Steingrueber, Enck, & Kloster-halfen, 2006), while systematic desensitization has been used to treat drug addiction (

Piane, 2000), phobias (

McCullough & Andrews, 2001), and tension headaches (

Deyl & Kaliappan, 1997), and to teach children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism to swallow pills (

Beck, Cataldo, Slifer, Pulbrook, & Guhman, 2005).

As another illustration, prescription drug advertisers regularly employ conditioning principles to encourage consumers to associate a brand-name medication with happy and improved lifestyles; once conditioned, consumers will likely favor the advertised drug over competitors’ medications and the much less expensive generic form. As a third example, taking the time to help patients relax and reduce their stress when applying some medical intervention—even a painful procedure—lessens the likelihood that patients will build up negative and anxious associations about medicine and health care.

Certain respondent conditioning concepts are especially useful in the healthcare setting. Stimulus generalization is the tendency of initial learning experiences to be easily applied to other similar stimuli. For example, when listening to friends and relatives describe a hospital experience, it becomes apparent that a highly positive or negative personal encounter may color patients’ evaluations of their hospital stays as well as their subsequent feelings about having to be hospitalized again. With more and varied experiences, individuals learn to differentiate among similar stimuli, at which point discrimination learning is said to have occurred. As an illustration, patients who have been hospitalized a number of times often have learned a lot about hospitalization. As a result of their experiences, they make sophisticated distinctions and can discriminate among stimuli (e.g., what the various noises mean and what the various health professionals do) that novice patients cannot. Much of professional education and clinical practice involves moving from being able to make generalizations to discrimination learning.

Spontaneous recovery is a useful respondent conditioning concept that needs to be given careful consideration in relapse prevention programs. The underlying principle operates as follows: Although a response may appear to be extinguished, it may recover and reappear at any time (even years later), especially when stimulus conditions are similar to those in the initial learning experience. Spontaneous recovery helps us understand why it is so difficult to completely eliminate unhealthy habits and addictive behaviors such as smoking, alcoholism, and drug abuse.

Another widely recognized approach to learning is

operant conditioning, which was developed largely by B. F.

Skinner (1974,

1989). Operant conditioning focuses on the behavior of the organism and the reinforcement that occurs after the response. A reinforcer is a stimulus or event applied after a response that strengthens the probability that the response will be performed again. When specific responses are reinforced on the proper schedule, behaviors can be either increased or decreased.

Table 3-1 summarizes the principal ways to increase and decrease responses by applying the contingencies of operant conditioning. Understanding the dynamics of learning presented in this table can prove useful to nurses in assessing and identifying ways to change individuals’ behaviors in the healthcare setting. The key is to carefully observe individuals’ responses to specific stimuli and then select the best reinforcement procedures to change a behavior.

Two methods to

increase the probability of a response are to apply positive or negative reinforcement after a response occurs. According to

Skinner (1974), giving positive reinforcement (i.e., reward) greatly enhances the likelihood that a response will be repeated in similar circumstances. As an illustration, although a patient moans and groans as he attempts to get up and walk for the first time after an operation, praise and encouragement (reward) for his efforts at walking (response) will improve the chances that he will continue struggling toward independence.

A second way to increase a behavior is by applying negative reinforcement after a response is made. This form of reinforcement involves the removal of an unpleasant stimulus through either escape conditioning or avoidance conditioning.

The difference between the two types of negative reinforcement relates to timing.

In escape conditioning, as an unpleasant stimulus is being applied, the individual responds in some way that causes the uncomfortable stimulation to cease. Suppose, for example, that when a member of the healthcare team is being chastised in front of the group for being late and missing meetings, she says something humorous. The head of the team stops criticizing her and laughs. Because the use of humor has allowed the team member to escape an unpleasant situation, chances are that she will employ humor again to alleviate a stressful encounter and thereby deflect attention from her problem behavior.

In avoidance conditioning, the unpleasant stimulus is anticipated rather than being applied directly. Avoidance conditioning has been used to explain some people’s tendency to become ill so as to avoid doing something they do not want to do. For example, a child fearing a teacher or test may tell his mother that he has a stomachache. If allowed to stay home from school, the child increasingly may complain of sickness to avoid unpleasant situations. Thus, when fearful events are anticipated, sickness, in this case, is the behavior that has been increased through negative reinforcement.

According to operant conditioning principles, behaviors also may be

decreased through either nonreinforcement or punishment.

Skinner (1974) maintained that the simplest way to extinguish a response is not to provide any kind of reinforcement for some action. For example, offensive jokes in the workplace may be handled by showing no reaction; after several such experiences, the joke teller, who more than likely wants attention—and negative attention is preferable to no attention—may curtail his or her use of offensive humor. Keep in mind, too, that desirable behavior that is ignored may lessen as well if its reinforcement is withheld.

If nonreinforcement proves ineffective, then punishment may be employed as a way to decrease responses, although this approach carries

many risks. Under punishment conditions, the individual cannot escape or avoid an unpleasant stimulus. Suppose, for example, a nursing student is continually late for class and noisily disrupts the class when she finally arrives, annoying both other students and the instructor. The instructor discovers there is no valid reason for the student’s lateness—the student says she overslept and did not allow sufficient time to find a parking place, and cites other factors she should have more control over. The instructor tries praising the student the few times she comes to class on time (positive reinforcement) and tries not paying attention to her when she arrives late (nonreinforcement), but the student continues to be late to class more often than she is on time. The student appears to enjoy the attention she receives. As a last resort, the instructor may try punishment, which involves applying a negative reinforcer and removing a positive reinforcer. The positive reinforcers to be removed are the attention the student receives and the fact that she really does not need to change her behavior to conform to classroom expectations. The instructor might tell the student that if she is late, she must come in the back door and sit in back of the class, making sure not to disturb anyone (removal of the positive reinforcer of attention). Each time the student is late, the instructor will make note in her grade book (negative reinforcer of not doing well in the course).

The problem with using punishment as a technique for teaching is that the learner may become highly emotional and may well divert attention away from the behavior that needs to be changed. Some people who are being punished become so emotional (sad or angry) that they do not remember the behavior for which they are being punished. One of the cardinal rules of operant conditioning is to “punish the behavior, not the person.” In the preceding example, the instructor must make it clear that she is punishing the student for being late and disrupting class rather than convey that she does not like the student.

If punishment is employed, it should be administered immediately after the response with no distractions or means of escape. Punishment must also be consistent and at the highest reasonable level (e.g., nurses who apologize and smile as they admonish the behavior of a staff member or client are sending mixed messages and are not likely to be taken seriously or to decrease the behavior they intend). Moreover, punishment should not be prolonged (bringing up old grievances or complaining about a misbehavior at every opportunity), but there should be a time-out following punishment to eliminate the opportunity for positive reinforcement. The purpose of punishment is not to do harm or to serve as a release for anger; rather, the goal is to decrease a specific behavior and to instill self-discipline.

Operant conditioning and discussions of punishment were more popular during the mid-20th century than they are currently. However, it is important for nurses to be aware of the many cautions about punishment because punishment continues to be used more than it should in the healthcare setting, and all too often in damaging ways.

The use of reinforcement is central to the success of operant conditioning procedures. For operant conditioning to be effective, it is necessary to assess which kinds of reinforcement are likely to increase or decrease behaviors for each individual. Not every client, for example, finds health practitioners’ terms of endearment rewarding. Comments such as “Very nice job, dear,” may be presumptuous or offensive to some clients. A second issue involves the timing of reinforcement. Through experimentation with animals and humans, researchers have demonstrated that the success of operant conditioning procedures partially depends on the schedule of reinforcement. Initial learning requires a continuous schedule, reinforcing the behavior quickly every time it occurs. If the desired behavior does not occur, then responses that approximate or resemble it

can be reinforced, gradually shaping behavior in the direction of the goal for learning. As an illustration, for geriatric patients who appear lethargic and unresponsive, nurses might begin by rewarding small gestures such as eye contact or a hand that reaches out, and then build on these friendly behaviors toward greater human contact and connection with reality. Once a response is well established, however, it becomes ineffective and inefficient to continually reinforce the behavior; reinforcement then can be administered on a fixed (predictable) or variable (unpredictable) schedule after a given number of responses have been emitted or after the passage of time.

Operant conditioning techniques provide relatively quick and effective ways to change behavior. Carefully planned programs using behavior modification procedures can readily be applied to health care. For example, computerized instruction and tutorials for patients and staff rely heavily on operant conditioning principles in structuring learning programs. In the clinical setting, the families of patients with chronic back pain have been taught to minimize their attention to the patients whenever they complain and behave in dependent, helpless ways, but to pay a lot of attention when the patients attempt to function independently, express a positive attitude, and try to live as normal a life as possible. Some patients respond so well to operant conditioning that they report experiencing less pain as they become more active and involved. A systematic review of physiotherapist-provided operant conditioning (POC) found moderate-level evidence showing that POC is more effective than a placebo intervention in reducing short-term pain in patients with subacute low back pain (

Bunzli, Gillham, & Esterman, 2011). Operant conditioning and behavior modification techniques also have been found to work well with some nursing home and long-term care residents, especially those who are losing their cognitive skills (

Proctor, Burns, Powell, & Tarrier, 1999).

The behaviorist theory is simple and easy to use, and it encourages clear, objective analysis of observable environmental stimulus conditions, learner responses, and the effects of reinforcements on people’s actions. There are, however, some criticisms and cautions to consider when relying on this theory. First, behaviorist theory is a teacher-centered model in which learners are assumed to be relatively passive and easily manipulated, which raises a crucial ethical question: Who is to decide what the desirable behavior should be? Too often the desired response is conformity and cooperation to make someone’s job easier or more profitable. Second, the theory’s emphasis on extrinsic rewards and external incentives reinforces and promotes materialism rather than self-initiative, a love of learning, and intrinsic satisfaction. Third, research evidence supporting behaviorist theory is often based on animal studies, the results of which may not be applicable to human behavior. A fourth shortcoming of behavior modification programs is that clients’ changed behavior may deteriorate over time, especially once they return to their former environment—an environment with a system of rewards and punishments that may have fostered their problems in the first place.

The next section moves from focusing on responses and behavior to considering the role of mental processes in learning.

Cognitive Learning Theory

Whereas behaviorists generally ignore the internal dynamics of learning, cognitive learning theorists stress the importance of what goes on inside the learner. Cognitive theory is assumed to comprise a number of subtheories and is widely used in education and counseling. According to this perspective, the key to learning and changing is the individual’s cognition (perception, thought, memory, and ways of processing and structuring information). Cognitive learning—a highly

active process largely directed by the individual—involves perceiving the information, interpreting it based on what is already known, and then reorganizing the information into new insights or understanding (

Bandura, 2001;

Hunt, Ellis, & Ellis, 2004).

Cognitive theorists, unlike behaviorists, maintain that reward is not necessary for learning to take place. More important are learners’ goals and expectations, which create disequilibrium, imbalance, and tension that motivate learners to act. Educators trying to influence the learning process must recognize the variety of past experiences, perceptions, ways of incorporating and thinking about information, and diverse aspirations, expectations, and social influences that affect any learning situation. A learner’s metacognition, or understanding of her way of learning, influences the process as well. To promote transfer of learning, the learner must mediate or act on the information in some way. Similar patterns in the initial learning situation and subsequent situations facilitate this transfer.

Cognitive learning theory includes several wellknown perspectives, such as gestalt, information processing, human development, social constructivism, and social cognition theory. More recently, attempts have been made to incorporate considerations related to emotions within cognitive theory. Each of these perspectives emphasizes a particular feature of cognition; collectively, when pieced together, they indicate much about what goes on inside the learner. As the various cognitive perspectives are briefly summarized here, readers are encouraged to think of their potential applications in the healthcare setting. In keeping with cognitive principles of learning, being mentally active when processing the information encourages its retention in longer-term memory.

One of the oldest psychological theories is the

gestalt perspective, which emphasizes the importance of perception in learning and lays the groundwork for the various other cognitive perspectives that followed (

Kohler, 1947,

1969;

Murray, 1995). Rather than focusing on discrete stimuli, gestalt refers to the configuration or patterned organization of cognitive elements, reflecting the maxim that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” A principal assumption is that each person perceives, interprets, and responds to any situation in his or her own way. While many gestalt principles worth knowing have been identified (

Hilgard & Bower, 1966), the discussion here focuses on those that relate to health care.

A basic gestalt principle is that psychological organization is directed toward simplicity, equilibrium, and regularity. For example, study the bewildered faces of some patients listening to a complex, detailed explanation about their disease; what they actually desire most is a simple, clear explanation that settles their uncertainty and relates directly to them and their familiar experiences.

Another central gestalt principle that has several ramifications is the notion that perception is selective. First, because no one can attend to all possible surrounding stimuli at any given time, individuals orient themselves to certain features of an experience while screening out or ignoring other features. Patients who are in severe pain or who are worried about their hospital bills, for example, may not attend to well-intentioned patient education information. Second, what individuals pay attention to and what they ignore are influenced by a host of factors: past experiences, needs, personal motives and attitudes, reference groups, and the particular structure of the stimulus or situation (

Sherif & Sherif, 1969). Assessing these internal and external dynamics has a direct bearing on how a health educator approaches any learning situation with an individual or group. Moreover, because individuals vary widely with regard to these and other characteristics, they will perceive, interpret, and respond to the same event in different ways, perhaps distorting reality to fit their goals and expectations. This tendency helps

explain why an approach that is effective with one client may not work with another client. People with chronic illnesses—even different people with the same illness—are not alike, and helping any patient with disease or disability includes recognizing each person’s unique perceptions and subjective experiences (

Imes, Clance, Gailis, & Atkeson, 2002).

Information processing is a cognitive perspective that emphasizes thinking processes: thought, reasoning, the way information is encountered and stored, and memory functioning (

Gagné, 1985;

Sternberg, 2006). How information is incorporated and retrieved is useful for nurses to know, especially in relation to older people’s learning (

Hooyman & Kiyak, 2005;

Kessels, 2003).

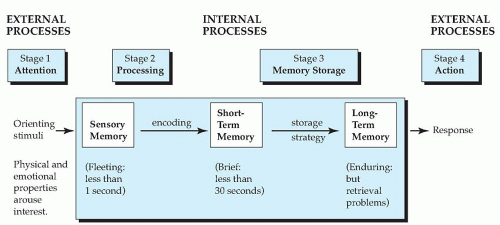

Figure 3-2 illustrates an information-processing model of memory functioning. Tracking learning through the various stages of this model is helpful in assessing what happens to information as each learner perceives, interprets, and remembers it, which in turn may suggest ways to improve the structure of the learning situation as well as ways to correct misconceptions, distortions, and errors in learning.

The first stage in the memory process involves paying attention to environmental stimuli; attention, then, is the key to learning. Thus, if a client is not attending to what a nurse educator is saying, perhaps because the client is weary or distracted, it would be prudent for the educator to try the explanation at another time when the client is more receptive and attentive.

In the second stage, the information is processed by the senses. Here it becomes important to consider the client’s preferred mode of sensory processing (visual, auditory, or motor manipulation) and to ascertain whether he or she has any sensory deficits.

In the third stage of the memory process, the information is transformed and incorporated (encoded) briefly into short-term memory, after which it suffers one of two fates: The information is disregarded and forgotten, or it is stored in longterm memory. Long-term memory involves the organization of information by using a preferred

strategy for storage (e.g., imagery, association, rehearsal, or breaking the information into units). Although long-term memories are enduring, a central problem is retrieving the stored information at a later time.

The last stage in the memory-processing model involves the action or response that the individual undertakes on the basis of how information was processed and stored. Education requires assessing how a learner attends to, processes, and stores the information that is presented as well as finding ways to encourage the retention and retrieval processes. Errors are corrected by helping learners reprocess what needs to be learned (

Kessels, 2003).

In general, cognitive psychologists note that memory processing and the retrieval of information are enhanced by organizing that information and making it meaningful. A widely used descriptive model has been provided by Robert

Gagné (1985). Subsequently, Gagné and his colleagues outlined nine events and their corresponding cognitive processes that activate effective learning (

Gagné, Briggs, & Wagner, 1992):

Gain the learner’s attention (reception)

Inform the learner of the objectives and expectations (expectancy)

Stimulate the learner’s recall of prior learning (retrieval)

Present information (selective perception)

Provide guidance to facilitate the learner’s understanding (semantic encoding)

Have the learner demonstrate the information or skill (responding)

Give feedback to the learner (reinforcement)

Assess the learner’s performance (retrieval)

Work to enhance retention and transfer through application and varied practice (generalization)

In employing this model, instructors must carefully analyze the requirements of the activity, design and sequence the instructional events, and select appropriate media to achieve the outcomes.

Within the information-processing perspective,

Sternberg (1996) reminds educators to consider styles of thinking, which he defines as “a preference for using abilities in certain ways” (p. 347). Thinking styles concern differences, he notes, rather than judgments of “better” versus “worse.” In education, the instructor’s task is to get in touch with the learner’s way of processing information and thinking. Some implications for health care are the need to carefully match jobs with styles of thinking, to recognize that people may shift from preferring one style of thinking to another, and, most important, to appreciate and respect the different styles of thinking reflected among the many players in the healthcare setting. Yet striving for a match in styles is not always necessary or desirable.

Tennant (2006) notes that adult learners may actually benefit from grappling with views and styles of learning unlike their own, which may promote maturity, creativity, and a greater tolerance for differences. Because nurses are expected to instruct a variety of people with diverse styles of learning, Tennant’s suggestion has interesting implications for nursing education programs.

The information-processing perspective is particularly helpful for assessing problems in acquiring, remembering, and recalling information. Some strategies include the following:

1. Have learners indicate how they believe they learn (metacognition)

2. Ask them to describe what they are thinking as they are learning

3. Evaluate learners’ mistakes

4. Give close attention to learners’ inability to remember or demonstrate information

For example, forgetting or having difficulty in retrieving information from long-term memory is a major stumbling block in learning. This problem may occur because the information has faded

from lack of use, other information interferes with its retrieval (what comes before or after a learning session may well confound storage and retrieval), or individuals are motivated to forget for a variety of conscious and unconscious reasons. This material on memory processing and functioning is highly pertinent to healthcare practice—whether in developing health education brochures, engaging in one-to-one patient education, delivering a staff development workshop, preparing community health lectures, or studying for courses and examinations. Focusing on attention, storage, and memory is essential in the patient education of older adults, including the identification of fatigue, medications, and anxieties that may interfere with learning and remembering (

Kessels, 2003).

Heavily influenced by gestalt psychology,

cognitive development is a third perspective on learning that focuses on qualitative changes in perceiving, thinking, and reasoning as individuals grow and mature (

Santrock, 2011;

Crandell, Crandell, & Vander Zanden, 2012). Cognitions are based on how external events are conceptualized, organized, and represented within each person’s mental framework or schema, which in turn is partially dependent on the individual’s stage of development in perception, reasoning, and readiness to learn.

Much of the theory and research in this area has been concerned with identifying the characteristics and advances in the thought processes of children and adolescents. A principal assumption is that learning is a developmental, sequential, and active process that transpires as the child interacts with the environment, makes discoveries about how the world operates, and interprets these discoveries in keeping with what she knows (schema).

Jean Piaget is the best known of the cognitive developmental theorists. His observations of children’s perceptions and thought processes at different ages have contributed much to our recognition of the unique, changing abilities of youngsters to reason, conceptualize, communicate, and perform (

Piaget & Inhelder, 1969). By watching, asking questions, and listening to children, Piaget identified and described four sequential stages of cognitive development: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operations, and formal operations. These stages become evident over the course of infancy, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence, respectively. According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive learning, children take in information as they interact with people and the environment. They either make their experiences fit with what they already know (assimilation) or change their perceptions and interpretations in keeping with the new information (accommodation). Nurses and family members need to determine what children are perceiving and thinking in a given situation. As an illustration, young children usually do not comprehend fully that death is final. They respond to the death of a loved one in their own way, perhaps asking God to give back the dead person or believing that if they act like a good person, the deceased loved one will return to them (

Gardner, 1978).

Proponents of the cognitive development perspective evidence some differences in their views that are worth considering by nurse educators. For example, while Piaget stresses the importance of perception in learning and views children as little scientists exploring, interacting, and discovering the world in a relative solitary manner, Russian psychologist Lev

Vygotsky (1986) emphasizes the significance of language, social interaction, and adult guidance in the learning process. When teaching children, Vygotsky says the job of adults is to interpret, respond, and give meaning to children’s actions. Rather than the discovery method favored by Piaget, Vygotsky advocates clear, well-designed instruction that is carefully structured to advance each person’s thinking and learning.

In practice, some children may learn more effectively by discovering and putting pieces

together on their own, whereas other children benefit from a more social and directive approach. It is the health educator’s responsibility to identify the child’s or teenager’s stage of thinking, to provide experiences at an appropriate level for the child to actively discover and participate in the learning process, and to determine whether a child learns best through language and social interaction or through perceiving and experimenting in his or her own way. Research suggests that young children’s learning is often more solitary, whereas older children may learn more readily through social interaction (

Palincsar, 1998).

What do cognitive developmental theorists say about adult learning? First, although the cognitive stages develop sequentially, some adults never reach the formal operations stage. These adults may learn better from explicitly concrete approaches to health education. Second, adult developmental psychologists and gerontologists have proposed advanced stages of reasoning in adulthood that go beyond formal operations. For example, it is not until the adult years that people become better able to deal with contradictions, synthesize information, and more effectively integrate what they have learned—characteristics that differentiate adult thought from adolescent thinking (

Kramer, 1983). Third, older adults may demonstrate an advanced level of reasoning derived from their wisdom and life experiences, or they may reflect lower stages of thinking resulting from lack of education, disease, depression, extraordinary stress, or medications (

Hooyman & Kiyak, 2005).

Research indicates that adults generally do better when offered opportunities for self-directed learning (emphasizing learner control, autonomy, and initiative), an explicit rationale for learning, a problem-oriented rather than subject-oriented approach, and opportunities to use their experiences and skills to help others (

Tennant, 2006). Also, educators must keep in mind that anxiety, the demands of adult life, and childhood experiences may interfere with learning in adulthood.

Cognitive theory has been criticized for neglecting the social context. To counteract this omission, the effects of social factors on perception, thought, and motivation are receiving increased attention. Social constructivism and social cognition are two increasingly popular perspectives within cognitive theory that take the social milieu into account.

Drawing heavily from gestalt psychology and developmental psychology, social constructivists take issue with some of the highly rational assumptions of the information-processing view and build on the work of John Dewey, Jean Piaget, and Lev Vygotsky (

Palincsar, 1998). These theorists posit that individuals formulate or construct their own versions of reality and that learning and human development are richly colored by the social and cultural context in which people find themselves. A central tenet of the social constructivist approach is that ethnicity, social class, gender, family life, past history, self-concept, and the learning situation itself all influence an individual’s perceptions, thoughts, emotions, interpretations, and responses to information and experiences. A second principle is that effective learning occurs through social interaction, collaboration, and negotiation (

Shapiro, 2002).

According to this view, the players in any healthcare setting may have differing perspectives on external reality, including distorted perceptions and interpretations. Every person operates on the basis of his or her unique representations and interpretations of a situation, all of which have been heavily influenced by that individual’s social and cultural experiences. The impact of culture cannot be ignored, and learning is facilitated by sharing beliefs, by acknowledging and challenging differing conceptions, and by negotiating new levels of conceptual understanding (

Marshall, 1998). Cooperative learning and selfhelp groups are examples of social constructivism in action. Given the rapidly changing age and ethnic composition in the United States, the social

constructivist perspective has much to contribute to health education and health promotion efforts.

Rooted in social psychology, the social cognition perspective reflects a constructivist orientation and highlights the influence of social factors on perception, thought, and motivation. A host of scattered explanations can be found under the rubric of social cognition (

Fiske & Taylor, 1991;

Moskowitz, 2005), which, when applied to learning, emphasize the need for instructors to consider the dynamics of the social environment and groups on both interpersonal and intrapersonal behavior. As an illustration, attribution theory focuses on the cause-and-effect relationships and explanations that individuals formulate to account for their own and others’ behavior and the way in which the world operates. Many of these explanations are unique to the individual and tend to be strongly colored by cultural values and beliefs. For example, patients with certain religious views or a particular type of parental upbringing may believe that their disease is a punishment for their sins (internalizing blame); other patients may attribute their disease to the actions of others (externalizing blame). From this perspective, patients’ attributions may or may not promote wellness and well-being. The route to changing health behaviors is to change distorted attributions. Nurses’ prejudices, biases (positive and negative), and attributions need to be considered as well in the healing process.

Cognitive theory has been criticized for neglecting emotions, and recent efforts have been made to incorporate considerations related to emotions within a cognitive framework, an approach known as the

cognitive-emotional perspective. As

Eccles and Wigfield (2002) comment, “‘Cold’ cognitive models cannot adequately capture conceptual change; there is a need to consider affect as well” (p. 127).

Several slightly different cognitive orientations to emotions have been proposed and are briefly summarized here:

Empathy and the moral emotions (e.g., guilt, shame, distress, moral outrage) play a significant role in influencing children’s moral development and in motivating people’s prosocial behavior and ethical responses (

Hoffman, 2000).

Memory storage and retrieval, as well as moral decision making, involve both cognitive and emotional brain processing, especially in response to situations that directly involve the self and are stressful (

Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001).

Emotional intelligence (EI) entails an individual managing his emotions, motivating himself, reading the emotions of others, and working effectively in interpersonal relationships, which some argue is more important to leadership, social judgment, and moral behavior than cognitive intelligence is (

Goleman, 1995).

Self-regulation includes monitoring cognitive processes, emotions, and the individual’s surroundings to achieve goals, which is considered a key factor to successful living and effective social behavior (

Eccles & Wigfield, 2002).

The implications are that nursing and other health professional education programs would do well to exhibit and encourage empathy and emotional intelligence in working with patients, family, and staff and to attend to the dynamics of self-regulation as a way to promote positive personal growth and effective leadership. Research indicates that the development of these attributes in self and patients is associated with a greater likelihood of healthy behavior, psychological well-being, optimism, and meaningful social interactions (

Brackett, Lopes, Ivcevic, Mayer, & Salovey, 2004).

A significant benefit of the cognitive theory to health care is its encouragement of recognizing and appreciating individuality and diversity in how people learn and process experiences. When applied to health care, cognitive theory has proved useful in formulating exercise programs

for breast cancer patients (

Rogers et al., 2004), understanding individual differences in bereavement (

Stroebe, Folkman, Hansson, & Schut, 2006), and dealing with adolescent depression in girls (

Papadakis, Prince, Jones, & Strauman, 2006). This theory highlights the wide variation in how learners actively structure their perceptions; confront a learning situation; encode, process, store, and retrieve information; and manage their emotions—all of which are affected by social and cultural influences. The challenge for educators is to identify each learner’s level of cognitive development and the social influences that affect learning, and then to find ways to foster insight, creativity, and problem solving. Difficulties may arise in ascertaining exactly what is transpiring inside the mind of each individual and in designing learning activities that encourage people to restructure their perceptions, reorganize their thinking, regulate their emotions, change their attributions and behavior, and create solutions.

The next learning theory combines principles from both the behaviorist and cognitive theories.