Chapter 18 Anxiety disorders

Introduction

Nurses frequently interact with anxious clients who are facing threats to their health and wellbeing. Experienced nurses become adept at reassuring and supporting clients in coping with the threat and crisis posed by ill health and trauma. Anxiety is a normal emotion experienced in varying degrees by everyone. Carpenito (2002, p 113) defines anxiety as ‘a state in which the individual/group experiences feelings of uneasiness (apprehension) and activation of the autonomic nervous system in response to a vague, non-specific threat’. Anxiety may manifest as:

Epidemiology

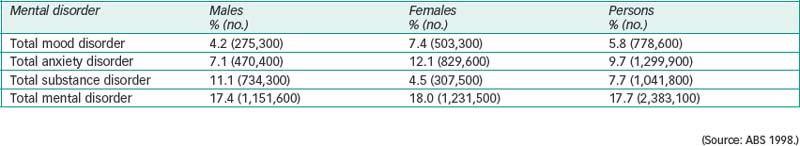

A more recent survey, Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey, used a similar methodology (Oakley Browne, Wells & Scott 2006). The New Zealand survey found that mental disorders were common, with a 12-month prevalence of 20.7%. Females had a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders than males. Māori and Pacific Island people generally had higher rates of mental disorder but, after adjusting for other sociodemographic differences, there was no difference in the 12-month prevalence of anxiety disorders between ethnic groups. Pacific Island and Māori people were less likely to seek treatment for mental health concerns, indicating the continuing presence of service access barriers in New Zealand.

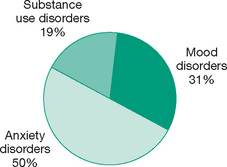

Among the major findings of the Australian survey were that people who live alone have a higher rate of anxiety disorder than people who live with one or more others. Women who live outside capital cities have a higher rate of anxiety disorder than females residing in cities (ABS 1998). Half of females with a mental disorder had an anxiety disorder, 31% had a mood disorder

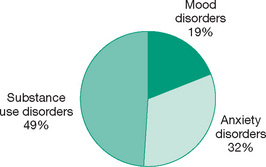

and 19% had a substance-use disorder (see Fig 18.1). Males with a mental disorder were most likely to have a substance-use disorder (49%), an anxiety disorder (32%) or a mood disorder (19%) (see Fig 18.2).

Figure 18.1 Prevalence of anxiety disorders compared to other mental disorders in Australian females (from ABS 1998)

Figure 18.2 Prevalence of anxiety disorders compared to other mental disorders in Australian males (from ABS 1998)

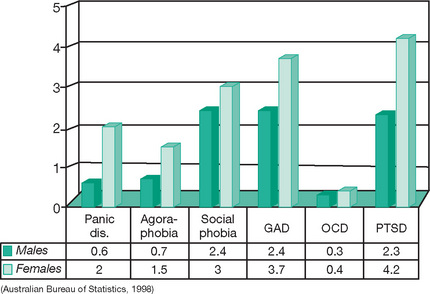

Different types of anxiety disorders had different prevalence rates. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was the most common anxiety disorder, followed by generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). The least common anxiety disorder was obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). All anxiety disorders were more common in females than males (see Fig 18.3).

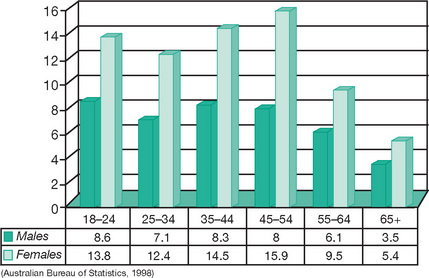

The prevalence of anxiety disorders varied with age. Anxiety disorders were most prevalent in the 18–54 year age groups. Prevalence declined after age 55 in both males and females (see Fig 18.4).

Individuals frequently had more than one anxiety disorder at a time and many also had another mental disorder. About a quarter of individuals with an anxiety, mood or substance-use disorder had at least one other mental disorder. Mood disorders and anxiety disorders were the most common comorbid conditions. The combination of anxiety and mood disorder made the largest contribution (56%) to disability from mental disorder in Australia (Teesson & Byrnes 2001, p 29). People with anxiety disorders reported an average of 2.1 days out of role—that is, they were unable to perform their usual roles of, for example, mother or worker, during the four weeks preceding the survey. This rate was higher than reported by people with a mood or substance-use disorder (ABS 1998).

Approximately 6.4 % of Australia’s total health budget is spent on specialist mental health services (Mental Health Council of Australia 2005). About half the mental health budget is allocated to psychotic and substance-use disorders. So although anxiety disorders afflict more than double the number of Australians with psychosis and substance dependence, they receive far less funding (Tolkien II Team 2006). Andrews, Issakidis & Slade (2001) liken this situation to salinity in comparison to floods. They note that governments swing into action to deal with dramatic events such as floods but ignore less dramatic events like salinity, which is more prevalent, can be arrested if managed early and causes considerable damage if ignored.

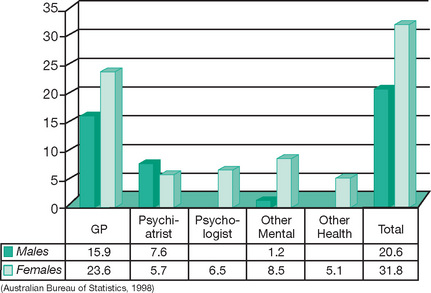

According to the NSMHW, only 28% of people with an anxiety disorder sought treatment. This is half the rate of people who sought help for a mood disorder. Of those who did seek professional help, most sought it from a general practitioner. Women were more likely than men to seek treatment for their anxiety disorder (see Fig 18.5) (ABS 1998).

Issakidis & Andrews (2002) examined data from the NSMHW (ABS 1998) to determine service utilisation and perceived need for care. Nearly 55% of respondents stated that they preferred to manage themselves. The reasons given by clients with an anxiety disorder for not accessing services were:

Issakidis & Andrews (2002) concluded that attitudinal barriers were more significant than structural barriers in seeking help. This study revealed a pressing need for public and professional education about the recognition and treatment of anxiety disorders.

Australian-born adults exhibit marginally higher rates of anxiety disorder than overseas-born Australians. This difference could be due to the healthy-migrant effect whereby people who are interested in migration and are accepted for migration are mentally healthier than those who are rejected (Andrews et al 1999).

Aetiology

Stress theory

Stress theory was developed by Hans Selye (1956, 1974), an endocrinologist. Selye identified three stages of stress: alarm reaction, resistance and exhaustion. Alarm reaction is the physiological response to stress. In resistance the physiological response continues as the ‘flight or fight’ reaction. The person may adapt to this heightened state of arousal and begin to relax, or they may be unable to relax and deplete their physiological and emotional resources, leaving little in reserve. This last phase is exhaustion.

Biological theories

Biological theories include genetic and neurochemical theories.

Genetic

Anxiety disorders tend to run in families but families share both genes and environment. First-degree relatives share the greatest number of genes. Anxiety disorders have an increased incidence in first-degree relatives. Twin studies, which aim to separate the influence of genes and environment, indicate that specific anxiety disorders are not inherited but that a general neurotic tendency encompassing anxiety, mood and eating disorders is inherited (Kendler et al 1995). Monozygotic twins have a concordance rate five times greater than that of dizygotic twins (American Psychiatric Association 2000). The development of a specific type of anxiety disorder then appears to be under the influence of the shared family environment (Crowe et al 1983).

Personality/temperament theory

Both genes and environment influence personality type. Each human being is unique. We all have our own personalities and no two people are exactly alike. Having said this, it is also true that people can be grouped into broad categories such as introverted or extroverted, passive or aggressive and so on. This consistency of behaviour is referred to as personality. Young children are in the process of developing a personality. The cluster of traits they consistently display is referred to as temperament. Temperament is being studied in a longitudinal study called the Australian Temperament Project (ATP), currently under way. The study aims to:

Analysis of data collected from the study indicates that a shy, inhibited temperament is associated with anxiety problems in adolescence (Prior et al 2000). The ATP study participants are currently in their late teens, and therefore it is not yet possible to tell whether the presence of an anxiety disorder in adolescence will progress into adulthood. However, other researchers have found that the presence of an anxiety disorder in adolescence increased the risk of having an anxiety or depressive disorder in adulthood (Pine et al 1998).

In reviewing the factors contributing to the development of anxiety disorders, Rapee (2002) concluded that a shy, inhibited temperament was the strongest predictor of the development of an anxiety disorder.

Psychoanalytic theory

Psychoanalytic theory postulates that anxiety occurs when the individual represses unacceptable thoughts and emotions. These unacceptable ideas and emotions then re-emerge in the form of anxiety. Freud (1936) believed that individuals mobilise defence mechanisms to control anxiety.

Interpersonal theory

Sullivan (1952) believed that anxiety was generated by interpersonal problems; for example, insecure parents may transmit anxiety to their children, or anxiety may arise when people do not conform to social norms. Rapee (2002) found that an overprotective parenting style was associated with an inhibited temperament and anxiety disorders in offspring (Rapee 2002).

Behavioural theory

Anxiety can be learned through experience and can be unlearned through new experiences. It makes sense that if a dog bites you, you can develop a fear of dogs. However, can people develop fears by watching others or by hearing about dangerous situations? Gerull & Rapee (2002) conducted a study to determine whether children learned to be fearful by watching others display fear. They showed toddlers a toy snake or spider paired with a picture of their mothers displaying either a positive, negative or neutral expression. Children were more likely to show fear of the toy when their mother displayed a negative expression. Mineka & Zinbarg (2006) argue that contemporary learning theory and research have the potential to explain the complex interplay between stressful learning events and contextual variables in the development and subsequent course of anxiety disorders.

Anxiety disorders

Panic attacks

A panic attack is not a discrete anxiety disorder. It can occur in any anxiety disorder and in many different mental disorders and medical conditions. A panic attack is defined as ‘a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort in the absence of real danger’ (DSM-IV-TR, APA 2000, p 430). Panic attacks have an abrupt onset and reach a peak within 10 minutes or less. To qualify as having a panic attack the individual must experience at least four of the classic somatic or cognitive symptoms listed in Box 18.1.

There are three types of panic attack:

Nursing interventions

During a panic attack

Stay with the client during the panic attack, as the panic will escalate if they are left on their own (Schultz & Videbeck 2002). The presence of another individual has a calming effect on the panicking client. An unattended client in panic may try to escape their current situation, and in doing so put themselves in danger.

Speak to the client in short, simple and audible sentences. A client at panic-level anxiety can only process one detail at a time and their sense of hearing can also be reduced (Stuart 2005a). During the panic attack take a directive approach; instruct the client to ‘Please sit down’ rather than asking, ‘Would you like to sit down?’. The client experiencing panic will not be able to decide what to do when offered the choice of whether to sit or not, and needs direction at this time. When the client has regained control they can resume responsibility for their own decisions.

Continue with a calm, reassuring tone: ‘You are having a panic attack’ and ‘I will stay with you’.

Danni [15] … was an outgoing, active teenager. ‘Then one day I went to school and this overwhelming fear came over me—to this day I can’t explain why … I started hyperventilating and my heart was racing. I felt sick and I had to go home.’ She said that was the start of a downhill slide … Danni tried many treatments, and became addicted to Serepax after being prescribed a series of medications (Mayer 2001, p 2).

Instruct the client to take a slow, medium breath (not a deep breath) through their nose and to hold it briefly before exhaling slowly through their nose. Aim to reduce the client’s respiration rate to 10 breaths per minute by using a 6-second cycle per respiration—for example, say ‘in-2–3, out-2–3’ (Andrews & Garrity 2000). Instruct the client to breathe using their diaphragm, not their chest. Continue coaching the client until their anxiety subsides. Some clients are aware that they are hyperventilating and try to slow their breathing, whereas others are not aware and make no attempt to reduce their respiration rate. Shallow, increased breathing or deep breathing results in the client exhaling too much carbon dioxide, which will manifest as dizziness and tingling or pins and needles in the extremities. To correct this you can ask the client to breathe into a paper bag. They will then re-breathe the carbon dioxide and regain the correct balance. However, some people find the prospect of having a bag over their mouth and nose too smothering or embarrassing and will become more panicky. Also, your chances of obtaining a paper bag in a first-aid situation in this age of plastic will be slim. You must be prepared to modify any anxiety reduction intervention to the individual concerned.

In a clinical setting, if the above techniques fail or the client is experiencing disorganised thoughts, perceptual disturbances or agitation that could escalate to aggression, consider administering a prescribed anti-anxiety medication that can be given as necessary. Even in a clinical situation, medication should only be used as a last resort because it communicates to the client that they are incapable of regaining control and sets up a future expectation that anxiety can be eliminated by medication. An oral dose from the benzodiazepine group (Therapeutic Guidelines Limited 2003), preferably in syrup form, followed by a glass of water will have a quicker onset of action than an intramuscular injection (Therapeutic Guidelines Limited 2003). Although benzodiazepines are very effective at reducing anxiety, they are associated with dependence and should only be used in the short term (preferably no longer than two weeks). Long-term use can result in withdrawal symptoms that mimic the anxiety symptoms that precipitated the client taking them in the first place, thus convincing the client that they cannot do without their ‘pills’ (National Prescribing Service 1999a).

After a panic attack

Give the client a list of the classic symptoms of a panic attack. Ask them to put a tick next to each symptom that they have experienced (Treatment Protocol Project 2004). Discuss the list with the client to determine whether they agree that what they have experienced was a panic attack. Some clients may continue to believe that they have a physical problem that has yet to be diagnosed.

Nurse’s story: Dealing with panic attack in A&E

Although Kerryn was unable to attend to her immediately, she responded to the young woman’s distress by allowing the client to remain near her while she attended to more urgent issues. Kerryn instructed the young woman to slow her breathing rate and explained that the tingling in her fingers was due to over-breathing and would abate once she was able to slow her breathing down. No further treatment other than empathy, respect and instruction on reducing the respiration rate was needed to resolve the panic attack.

a thorough physical examination to exclude a physical cause for their symptoms. Once a physical cause for the client’s symptoms has been excluded and the diagnosis of panic attack has been confirmed, no further follow-up is warranted, as one panic attack does not constitute an anxiety disorder. However, the client should be informed that if they have further panic attacks they should seek appropriate help early.

Panic disorder

Panic disorder is defined as ‘the presence of recurrent, unexpected panic attacks followed by at least one month of persistent concern about having another panic attack, or a significant behavioural change related to the attacks’ (APA 2000, p 433). The individual must have experienced at least two unexpected panic attacks to be diagnosed with panic disorder. There are two types of panic disorder: panic disorder without agoraphobia and panic disorder with agoraphobia. The frequency and severity of panic disorder varies widely from one panic attack per week for months, to daily panic attacks, separated by weeks or months without an attack. The characteristics of panic disorder are:

Comorbid disorders to panic disorder include depression, with rates varying from 10% to 65%. In one-third of clients, depression precedes the panic disorder. In two-thirds of clients, depression coincides with panic disorder. Clients will often self-medicate with alcohol or other medication and are at high risk of developing a substance-use disorder. Other anxiety disorders and numerous general medical conditions are also common in panic disorder (APA 2000). The case study of Ian illustrates role impairment and comorbidity associated with panic disorder.

The prevalence of mental disorders is much higher in clinical populations (ABS 1998). Panic disorder occurs in 10% of clients in mental health settings, in 10–30% of general medical clients (especially in vestibular, respiratory and neurology settings) and in up to 60% of clients in cardiology settings (APA 2000).

The outcome of treatment in panic disorder is varied. Six years after treatment, 30% of clients were well, 40–50% improved, and 20–30% were the same or worse (APA 2000).

Nursing interventions

Teaching plan: panic attacks

Ian … stopped functioning after leaving his job and then—temporarily—his partner and son went to stay in a hotel. ‘I still thought I could cure myself, it was all work-related and I just needed some peace. But … I realised how desperate I was. I went to bed and couldn’t move because I was absolutely terrified. I felt physically paralysed. I lay like that for two days. I’d try to get out of bed but my breathing was all over the place. I’d been on edge for so long’.

(Source: Kenny 2000, pp 20–1.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree