Chapter 11 Anticoagulation and heparin administration

Why doesn’t blood clot within the normal vascular system?

The lining of the blood vessels, the endothelium, is smooth, allowing the blood to flow freely through the vessels. The other surfaces of cells—vascular endothelial cells, platelets, and red blood cells—are gelatinous and hydrophilic, with a high water content. They have low interfacial tensions and have little tendency to adhere when intact.

How does heparin prevent coagulation?

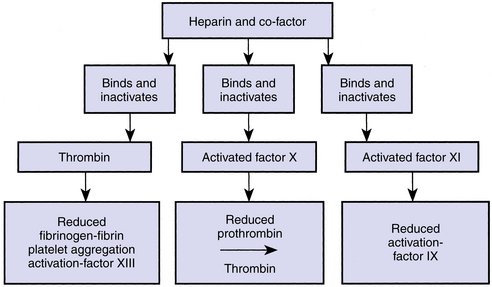

Heparin combines with a blood protein fraction called heparin cofactor (antithrombin III). The complex of heparin–antithrombin III combines with and inactivates thrombin, activated factor X, and activated factor XI, thus preventing clotting at all three stages of coagulation (Fig. 11-1). The conversion of prothrombin to thrombin is inhibited, as is the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Peak anticoagulant activity is reached 5 to 10 minutes after injection. The half-life is about 90 minutes for doses usually used in dialysis. The mechanism of heparin inactivation is not completely clear; it is metabolized by the liver and is taken up by the reticuloendothelial system.

What is the unit measurement of heparin?

A unit is the measure of a drug’s activity in the body. For heparin, a unit dose is the measure of the drug’s ability to block the blood’s natural clotting ability (anticoagulation). Heparin’s potency is determined by the dose of the drug required to produce a specific level of anticoagulation (FDA, 2010).

Heparin has recently gone through some new manufacturing controls and has a new reference standard for its unit dose as well as its potency. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests that dialysis practitioners expect a 10% reduction in the potency of the heparin marketed in the U.S. Heparin that is manufactured under the new USP unit will be labeled with an “N” next to the lot number (FDA, 2010). It is always prudent to use good clinical judgment and to monitor the patient’s response to heparin and to adjust the dose accordingly.

How is the heparin dosage determined?

The patient’s heparin dosage is prescribed by the physician and is generally based on the patient’s dry weight. Dosage adjustments need to be made if the patient has a change in weight, if the length of treatment changes, or if the dialyzer membrane changes. Erythropoietin may increase heparin requirements, necessitating an increase in the prescribed amount. The heparin dosage must be low enough to reduce the risk of bleeding yet high enough to prevent clotting of the extracorporeal circuit. With adequate heparinization, the patient will have better clearance of solutes through the dialyzer membrane. Adequate heparinization will also help the dialyzer to clear more thoroughly, allowing the patient to receive as many red blood cells as possible when the patient’s blood is returned to him or her at the end of the treatment. Because chronic outpatient dialysis units are not able to monitor clotting times due to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA) mandates, dialysis personnel must be attentive to indications that the patient may require more or less heparin. Clotting of the dialysis system, poor clearance of the dialyzer posttreatment, and inadequate urea clearance may indicate a need to increase heparin dosing. Excessive bleeding or bruising posttreatment may indicate a need to decrease heparin dosing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree