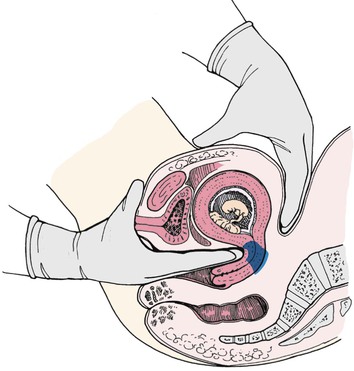

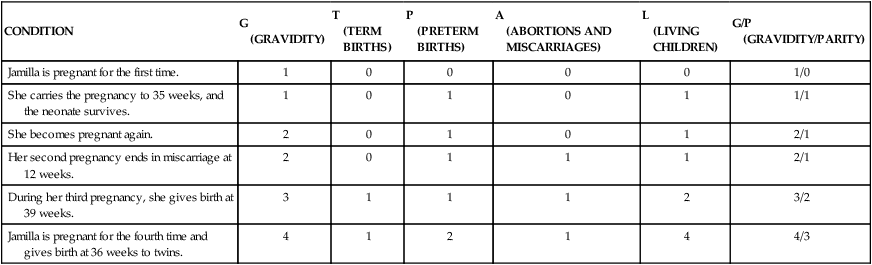

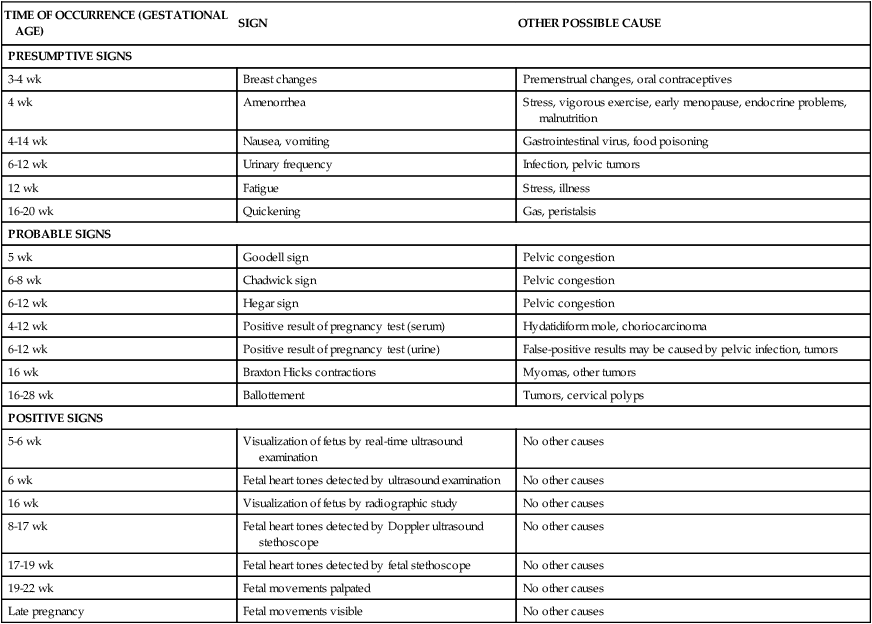

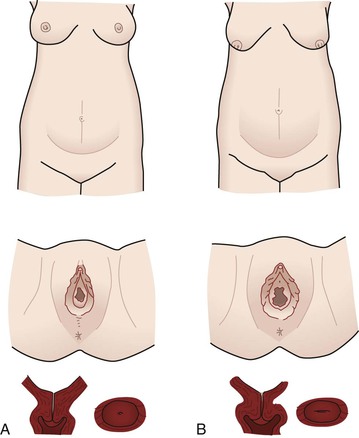

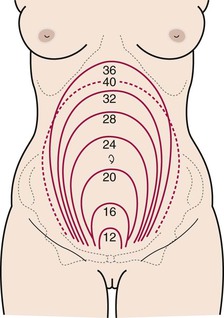

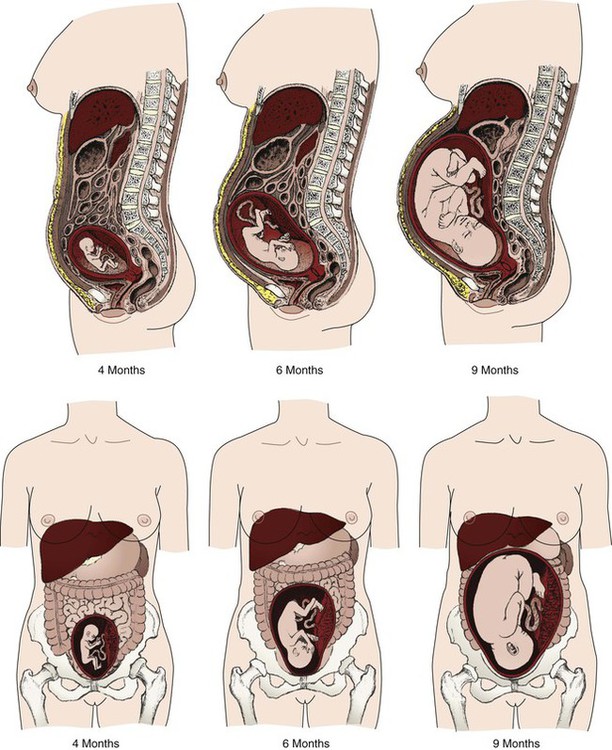

• Determine gravidity and parity by using the five- and two-digit systems. • Describe the various types of pregnancy tests, including the timing of tests and interpretation of results. • Explain the expected maternal anatomic and physiologic adaptations to pregnancy for each body system. • Differentiate among presumptive, probable, and positive signs of pregnancy. • Compare normal adult laboratory values with values for pregnant women. • Identify the maternal hormones produced during pregnancy, their target organs, and their major effects on pregnancy. • Compare the characteristics of the abdomen, vulva, and cervix of the nullipara and multipara. An understanding of the terms that are used to describe pregnancy and the pregnant woman is essential to the study of maternity care. Box 6-1 describes these terms. Two commonly used systems of summarizing the obstetrical history are discussed here. Gravidity and parity may be described with only two digits: The first digit represents the number of pregnancies the woman has had, including the present one; and parity is the number of pregnancies that have reached 20 or more weeks of gestation. For example, if the woman had twins at 36 weeks with her first pregnancy, parity would still be counted as one birth (gravida [G] 1, para [P]1) (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, Hauth, Gilstrap, & Wenstrom, 2005). If she becomes pregnant a second time, she would be G2 P1 until she gives birth at 38 weeks when she would then become G2 P2. Another system, which consists of five digits separated with hyphens, is commonly used in maternity centers. This system provides more information about the woman’s obstetric history, although it may not provide accurate information about parity since it provides information about births and not pregnancies reaching 20 weeks of gestation (Beebe, 2005). The first digit represents gravidity, the second digit represents the total number of term births, the third indicates the number of preterm births, the fourth identifies the number of abortions (miscarriage or elective termination of pregnancy), and the fifth is the number of children currently living. The acronym GTPAL (gravidity, term, preterm, abortions, living children) may be helpful in remembering this system of notation. For example, if a woman pregnant only once gives birth at week 34 and the infant survives, the abbreviation that represents this information is 1-0-1-0-1. During her next pregnancy, the abbreviation is 2-0-1-0-1. Additional examples are given in Table 6-1. TABLE 6-1 Obstetric History Using Five-Digit (GTPAL) System and Two-Digit (G/P)System Early detection of pregnancy allows early initiation of care. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is the earliest biochemical marker for pregnancy, and pregnancy tests are based on the recognition of hCG or a beta (β) subunit of hCG. Production of β-hCG begins as early as the day of implantation and can be detected as early as 7 to 10 days after conception (Blackburn, 2007). The level of hCG increases until it peaks at approximately 60 to 70 days of gestation and then declines until about 80 days of pregnancy. It remains stable until approximately 30 weeks and then gradually increases until term. Higher than normal levels of hCG may indicate abnormal gestation (e.g., fetus with Down syndrome), or multiple gestation; an abnormally slow increase or a decrease in hCG levels may indicate impending miscarriage (Cunningham et al., 2005). Many different pregnancy tests are available (Fig. 6-1). The wide variety of tests precludes discussion of each. The nurse should read the manufacturer’s directions for the test that is to be used. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing is the most popular method of testing for pregnancy. It uses a specific monoclonal antibody (anti-hCG) with enzymes to bond with hCG in urine. ELISA technology is the basis for most over-the-counter home pregnancy tests. With these one-step tests the woman usually applies urine to a strip or absorbent tipped applicator and reads the results. The test kits come with directions for collection of the specimen, the testing procedure, and reading of the results. A positive test result is indicated by a simple color change reaction or a digital reading. Most manufacturers of the kits provide a toll-free telephone number to call if users have concerns and questions about test procedures or results (see Teaching Guidelines). The most common error in performing home pregnancy tests is performing the test too early in pregnancy (Pagana & Pagana, 2006). Interpreting the results of pregnancy tests requires some judgment. The type of pregnancy test and its degree of sensitivity (ability to detect low levels of a substance) and specificity (ability to discern the absence of a substance) must be considered in conjunction with the woman’s history. This history includes the date of her last normal menstrual period (LNMP), her usual cycle length, and results of previous pregnancy tests. Knowing if the woman is a substance abuser and what medications she is taking is important because medications such as anticonvulsants and tranquilizers can cause false-positive results, whereas diuretics and promethazine can cause false-negative results (Pagana & Pagana, 2006). Improper collection of the specimen, hormone-producing tumors, and laboratory errors also may cause false results. Depending on the specific test, levels of hCG as low as 6.3 milli-international units/ml can be detected as early as the first day of a missed menstrual period as reported by Cole, Sutton-Riley, Khanlian, Borkovskaya, Rayburn, & Rayburn (2005). These researchers found that most of the over-the-counter pregnancy tests in the study were less sensitive (25 to 100 milli-international units/ml) and detected only a small percentage of pregnancies on the first day of a missed period even though most products claimed to be 99% accurate. Tomlinson, Marshall, and Ellis (2008) found that digital readings of low hCG levels (i.e., 25 milli-international units/ml) were more accurately interpreted by consumers than nondigital tests. Some of the physiologic adaptations are recognized as signs and symptoms of pregnancy. Three commonly used categories of signs and symptoms of pregnancy are presumptive (specific changes felt by the woman—e.g., amenorrhea, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, breast changes), probable (changes observed by an examiner—e.g., Hegar sign, ballottement, pregnancy tests), and positive (signs that are attributable only to the presence of the fetus—e.g., hearing fetal heart tones, visualization of the fetus, palpating fetal movements). Table 6-2 summarizes these signs of pregnancy in relation to when they might occur and other causes for their occurrence. TABLE 6-2 The pregnancy may “show” after the fourteenth week, although this depends to some degree on the woman’s height and weight. Abdominal enlargement may be less apparent in the nullipara with good abdominal muscle tone (Fig. 6-2). Posture also influences the type and degree of abdominal enlargement that occurs. In normal pregnancies, the uterus enlarges at a predictable rate. As the uterus grows, it may be palpated above the symphysis pubis some time between the twelfth and fourteenth weeks of pregnancy (Fig. 6-3). The uterus rises gradually to the level of the umbilicus at about 22 weeks of gestation and nearly reaches the xiphoid process at term. Between weeks 38 and 40, fundal height drops as the fetus begins to descend and engage in the pelvis (lightening) (see Fig. 6-3, dashed line). Generally, lightening occurs in the nullipara approximately 2 weeks before the onset of labor and at the start of labor in the multipara. The uterus normally rotates to the right as it elevates, probably because of the presence of the rectosigmoid colon on the left side, but the extensive hypertrophy (enlargement) of the round ligaments keeps the uterus in the midline. Eventually the growing uterus touches the anterior abdominal wall and displaces the intestines to either side of the abdomen (Fig. 6-4). Whenever a pregnant woman is standing, most of her uterus rests against the anterior abdominal wall, and this contributes to altering her center of gravity. At approximately 6 weeks of gestation, softening and compressibility of the lower uterine segment (the uterine isthmus) occur (Hegar sign) (Fig. 6-5). This change results in exaggerated uterine anteflexion during the first 3 months of pregnancy. In this position, the uterine fundus presses on the urinary bladder, causing the woman to have urinary frequency. Placental perfusion depends on the maternal blood flow to the uterus. Blood flow increases rapidly as the uterus increases in size. Although uterine blood flow increases 20-fold the fetoplacental unit grows more rapidly. Consequently, more oxygen is extracted from the uterine blood during the latter part of pregnancy (Cunningham et al., 2005). In a normal term pregnancy, one sixth of the total maternal blood volume is within the uterine vascular system. The rate of blood flow through the uterus averages 500 ml/min, and oxygen consumption of the gravid uterus increases to meet fetal needs. A low maternal arterial pressure, contractions of the uterus, and maternal supine position are three factors known to decrease blood flow. Estrogen stimulation may increase uterine blood flow. Doppler ultrasound examination can be used to measure uterine blood flow velocity, especially in pregnancies at risk because of conditions associated with decreased placental perfusion such as hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction, diabetes mellitus, and multiple gestation (Blackburn, 2007). By using an ultrasound device or a fetal stethoscope, the health care provider may hear the uterine souffle (sound made by blood in the uterine arteries that is synchronous with the maternal pulse) or the funic souffle (sound made by blood rushing through the umbilical vessels and synchronous with the fetal heart rate). A softening of the cervical tip called Goodell sign may be observed at approximately the beginning of the sixth week in a normal, unscarred cervix. This sign is brought about by increased vascularity, slight hypertrophy, and hyperplasia (increase in the number of cells) of the muscle and its collagen-rich connective tissue, which becomes loose, edematous, highly elastic, and increased in volume. The glands near the external os proliferate beneath the stratified squamous epithelium, giving the cervix the velvety appearance characteristic of pregnancy. Friability is increased and may cause slight bleeding after coitus with deep penetration or after vaginal examination. Pregnancy also can cause the squamocolumnar junction, the site for obtaining cells for cervical cancer screening, to be located away from the cervix. Because of all these changes, evaluation of abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) tests during pregnancy can be complicated. A careful assessment of all pregnant women is important, however, because approximately 3% of all cervical cancers are diagnosed during pregnancy (Copeland & Landon, 2007). The cervix of the nullipara is rounded. Lacerations of the cervix almost always occur during the birth process. With or without lacerations, however, after childbirth, the cervix becomes more oval in the horizontal plane, and the external os appears as a transverse slit (see Fig. 6-2). Passive movement of the unengaged fetus is called ballottement and can be identified generally between the sixteenth and eighteenth week. Ballottement is a technique of palpating a floating structure by bouncing it gently and feeling it rebound. In the technique used to palpate the fetus, the examiner places a finger in the vagina and taps gently upward, causing the fetus to rise. The fetus then sinks, and a gentle tap is felt on the finger (Fig. 6-6).

Anatomy and Physiology of Pregnancy

Gravidity and Parity

CONDITION

G

(GRAVIDITY)

T

(TERM BIRTHS)

P

(PRETERM BIRTHS)

A

(ABORTIONS AND MISCARRIAGES)

L

(LIVING CHILDREN)

G/P

(GRAVIDITY/PARITY)

Jamilla is pregnant for the first time.

1

0

0

0

0

1/0

She carries the pregnancy to 35 weeks, and the neonate survives.

1

0

1

0

1

1/1

She becomes pregnant again.

2

0

1

0

1

2/1

Her second pregnancy ends in miscarriage at 12 weeks.

2

0

1

1

1

2/1

During her third pregnancy, she gives birth at 39 weeks.

3

1

1

1

2

3/2

Jamilla is pregnant for the fourth time and gives birth at 36 weeks to twins.

4

1

2

1

4

4/3

Pregnancy Tests

Adaptations to Pregnancy

Signs of Pregnancy

TIME OF OCCURRENCE (GESTATIONAL AGE)

SIGN

OTHER POSSIBLE CAUSE

PRESUMPTIVE SIGNS

3-4 wk

Breast changes

Premenstrual changes, oral contraceptives

4 wk

Amenorrhea

Stress, vigorous exercise, early menopause, endocrine problems, malnutrition

4-14 wk

Nausea, vomiting

Gastrointestinal virus, food poisoning

6-12 wk

Urinary frequency

Infection, pelvic tumors

12 wk

Fatigue

Stress, illness

16-20 wk

Quickening

Gas, peristalsis

PROBABLE SIGNS

5 wk

Goodell sign

Pelvic congestion

6-8 wk

Chadwick sign

Pelvic congestion

6-12 wk

Hegar sign

Pelvic congestion

4-12 wk

Positive result of pregnancy test (serum)

Hydatidiform mole, choriocarcinoma

6-12 wk

Positive result of pregnancy test (urine)

False-positive results may be caused by pelvic infection, tumors

16 wk

Braxton Hicks contractions

Myomas, other tumors

16-28 wk

Ballottement

Tumors, cervical polyps

POSITIVE SIGNS

5-6 wk

Visualization of fetus by real-time ultrasound examination

No other causes

6 wk

Fetal heart tones detected by ultrasound examination

No other causes

16 wk

Visualization of fetus by radiographic study

No other causes

8-17 wk

Fetal heart tones detected by Doppler ultrasound stethoscope

No other causes

17-19 wk

Fetal heart tones detected by fetal stethoscope

No other causes

19-22 wk

Fetal movements palpated

No other causes

Late pregnancy

Fetal movements visible

No other causes

Reproductive System and Breasts

Uterus

Changes in size, shape, and position.

Uteroplacental blood flow.

Cervical changes.

Changes related to the presence of the fetus.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Anatomy and Physiology of Pregnancy

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access