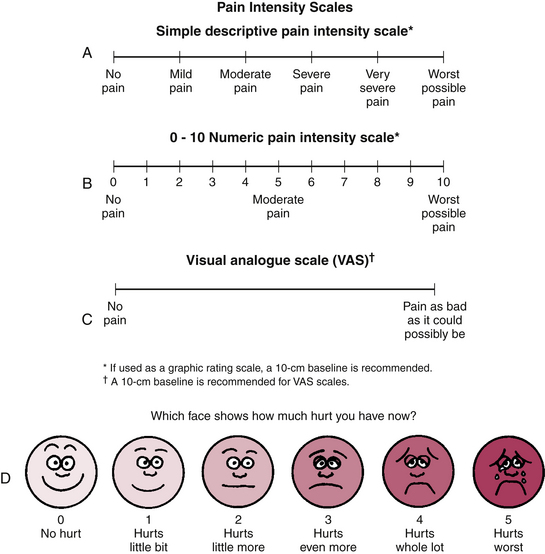

Chapter 11 1 Identify common aging stereotypes. 2 Describe the changes associated with aging. 3 Describe the effect of age-related changes on occupational performance. 4 Hypothesize factors contributing to fall risk. 5 Analyze cognitive and perceptual abilities in activity. 6 Differentiate between activity-, client-, cognition-, perception-, and sensation-focused activity analyses. 7 Explain grading and adapting activities for older adults. This chapter on working with older people provides learning opportunities interspersed throughout to promote the learner’s occupation-based critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Readers may want to reference the occupational therapy practice framework (OTPF),4 which facilitates understanding of the chapter contents and assists readers in transforming the OTPF into clinical and community practice. Levels of specific client factors change throughout life based on genetics, context, lifestyle, and various other reasons. The first exercise in thinking about aging involves brainstorming. Look over the client factors of the OTPF4 (pp 634-637) and think about how we anticipate or expect that these will change as one heads into old age. For this exercise, think about how society or the general population would predict change (e.g., aging stereotypes). Do this before reading the rest of the chapter (Table 11-1). TABLE 11-1 Aging Stereotypes—Anticipated Changes Most readers find that the list is composed of more negative changes and traits than positive changes and traits. People anticipate more problems as they age (e.g., increased forgetfulness, decreased endurance). Occupational examples (right column of Table 11-1) are important to consider because they focus on the stereotypes of aging, many of which are only partially true; some are patently false. There are no right or wrong answers, because expectations are based on cultural norms and ideas that become ingrained over time. Levy,31 who studied the stereotypes of aging extensively, found negative stereotypes about aging among children as young as preschool age, who already describe older people as more helpless and less capable of taking care of themselves. By the time people reach old age, these perceptions are often internalized and are even more negative than ever. Several sensory changes occur as people age. Vision is affected early in life, beginning in one’s 20s, and this sensory change is one that is considered to be senescent (or caused by aging). Predictable changes occur in the structures of the eye, including the cornea and the lens, both of which are important for focusing images on the retina at the back of the eye. The cornea becomes thicker and less transparent, and the lens also becomes more opaque and less elastic, resulting in difficulty accommodating to new visual stimuli. Already in middle age the majority of people have the condition of presbyopia, or farsightedness, resulting in the need for reading glasses to compensate for these structural changes. The iris, or colored portion of the eye, which regulates the amount of light entering the eye by dilating and constricting as needed, contains a set of muscles that atrophy over time, resulting in more constricted pupils, which then require additional lighting to focus on visual stimuli. In addition, the structures in the retina—cones associated with fine, close, and color vision and rods associated with vision in dim circumstances—also undergo gradual cell death.44 Therefore, it is little wonder that older people have poorer night vision as well as poorer close vision. However, under normal circumstances, corrective lenses can bring visual acuity up to a level such that impaired sight will not interfere with day-to-day tasks, even for those in their 80s and beyond.45 Generally speaking, occupational therapy practitioners can assist people who have low vision by increasing the size of stimuli, increasing the contrast between the visual stimuli and the environment, and by improving the lighting (brighter task lighting and less glare). Intervention on the part of the occupational therapy practitioner requires an assessment of the effect of decreased vision on function. The general principles of better lighting, higher contrast, and larger size tend to fit for these conditions as well. Total blindness, which occurs in approximately 10% of those who are visually impaired,13 obviously requires different tactics, including using other sensory systems to compensate, organizing the environment, setting up routines not dependent on intact vision, educating the client and his or her family, and referrals to vision specialists (Figure 11-1). Presbycusis is defined as an age-related decrease in the sense of hearing. There are two types of hearing loss: conductive and sensorineural. Conductive hearing loss is easier to manage because it involves problems with the outer or middle ear; examples include a buildup of cerumen (ear wax) or the ears becoming stopped up because of an upper respiratory infection. Sensorineural hearing loss is more permanent and more difficult to compensate for or to correct. It involves damage to or death (apoptosis) of the hair cells (cilia) in the inner ear. This hair cell loss also is associated with a higher prevalence of vertigo as people get older, with 18.4% of those 85 and older reporting bouts of dizziness.41 The density of hair cells in the inner ear decreases as people age, and these sensitive sensory cells can also be damaged by loud noise, especially, but not exclusively, of extended duration.17 Occupational therapy practitioners can work with people who have hearing loss to help them compensate for and adapt to the environment for improved ability to understand the spoken word. For example, older people have more difficulty tuning out background noise and hearing consonants, and men especially tend to lose the ability to hear higher-pitched voices.44 To improve an older person’s ability to understand, speaking directly to the person in a lower pitched (though not necessarily louder) voice can be helpful, along with ensuring that the environment in which conversations take place is not overly distracting. For example, it will be more difficult to enjoy dinner conversation with an older person in a noisy restaurant. Hearing aids are only useful if they are worn and working, which is perhaps an obvious detail, but one that is often ignored in day-to-day life. In old age people often develop hyposmia, which is a decrease in sense of smell, or anosmia, which is the absence of olfactory or smell sensation. Older people are less sensitive to odors in general, and men are more significantly affected than women. Different odors are differentially affected by age. For example, sensitivity to banana or rose scents is more likely to be maintained, whereas sensitivity to vanilla or musky odors is more likely to decrease from decade to decade.42 The loss of smell sensation is generally insidious, and quite often older people are not aware of the loss. Nordin, Monsch, and Murphy38 found that 77% of the older people who were found to have significant olfactory sensory losses, but otherwise had no disease, reported that their sense of smell was normal. Beside age itself, disease states, medications and drugs, airway obstruction, and environmental pollutants can all affect one’s sense of smell. Hyposmia and anosmia can have a negative effect on independent living skills, and this loss may need adaptations to be appropriately managed. Table 11-2 allows the reader to spend time thinking about the effect of decreased olfactory sense. This table could be replicated for any of the senses and is provided as just one example. TABLE 11-2 Olfaction and its Effect on Performance ADL, Activity of daily living; IADL, instrumental activity of daily living. Taste is closely related to the sense of smell. Not only does the number of taste buds decrease significantly over time, but the types of taste buds are differentially affected over time as well. The ability to detect salty and bitter decreases more rapidly than the ability to detect sweet and sour.42 Therefore, older people tend to need higher thresholds of salty flavor to taste the saltiness, but their taste buds for sweet flavors are better maintained. This pattern of change with aging is one reason why older people may tend to over-salt their food and rely too heavily on sweets. Finally, somesthesis (sense of touch), proprioception (sense of body in space), and kinesthesia (sense of movement of the body) are not significantly affected by aging per se. The number of corpuscles (e.g., pacinian and Meissner for pressure and light touch, respectively) does decrease, but overall touch sensitivity remains intact throughout typical aging. However, a significant portion of older people may lose sensory functioning in this realm. Acquired brain injury or cerebrovascular accidents (sustained by 795,000 people in the United States per year, three fourths of whom are 65 or older27) are often associated with decreased sensation, including discriminative touch, proprioception, and kinesthesia.29 This is not normal aging, but a common problem found among those who are older. Even a slight decline in proprioception and vestibular sense (along with muscle weakness and other potential risk factors) can lead to increased risk of falls. Pain is also associated with sensory functioning. It plays a valuable role in protecting the body from harm, but it can also be a nuisance and can significantly interfere with daily functioning. Some have contended that increased pain is just a part of the normal aging process, but others do not agree. Farrell19 reported that, although studies have found a slightly decreasing mean for pain threshold over time, they also have found more heterogeneity among the older population, resulting in some 90-year-olds, for instance, having the same threshold for pain as typical 30-year-olds. One cannot assume that older people feel less (or more) pain than any other age group. The assessment of pain (using a 1 to 10 or a smiley face–sad face continuum) can be a valuable addition to occupational therapy intervention (Figure 11-2). Physical changes occur with age; some are chronologic, whereas others are due to extrinsic factors. The changes discussed in this chapter include range of motion (ROM), strength, endurance, and coordination. ROM, or how far each joint moves through space, does decrease slightly (mean range) as people get older, but when aging is typical, the older person’s ROM remains within functional limits, meaning that the joint range is adequate to complete the tasks one needs to complete. Strength is related to ROM. Those who have good strength (4 or 5 out of 5) generally have full ROM, unless there is a joint problem, such as an obstruction. We need adequate strength to do our activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Depending on the demands of the tasks, the amount of ROM and strength required can vary. For example, shoveling snow requires very good strength, whereas typing on a keyboard requires very little. Box 11-1 challenges readers to think of reasons why, other than old age, ROM or strength might be below what is considered normal (Figure 11-3). Arthritis, perhaps the most common cause of joint problems, including decreased ROM and muscle strength, is likely near the top of the list. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that approximately 50 million adults in the United States (or 22% of the adult population) report that they have diagnosed arthritis, and 21 million (9% of adults) report that they have arthritis to the level that it impedes their functional performance.16 Sarcopenia is the loss of strength in skeletal muscle as one ages, starting in middle age.28 Using a large-scale national sample, Janssen, Heymsfeld, and Ross28 found the majority of people older than 60 (52% of men and 69% of women) have a strength level at least one standard deviation below the average of those aged 18 to 39. Those who had losses in the range of more than two standard deviations below the mean of the younger group were more likely to have functional limitations affecting daily functioning (odds ratios twice as great for men and three times as great for women). Endurance is the ability to sustain engagement in an activity that involves physical strength. Someone may be very strong but have limited endurance, or have good endurance for tasks that require only limited strength. Generally those with good endurance also have a functional level of strength. Not only is endurance less affected by age than strength, but a meta-analysis of 13 exercise training programs of 30 weeks or longer in duration demonstrated that aerobic exercise can improve endurance as well as strength and range of motion.24 Control of voluntary movement, or fine and gross motor control, allows people to manipulate items and to smoothly move the body through space. Praxis is another way to describe purposeful motor actions. Fortunately, typical aging does not substantially affect coordination. Practicing tasks over the course of years generally allows people to improve or at least maintain performance. An example of this is Salthouse’s43 description of older secretaries who do not significantly lose typing speed. He theorized that through “anticipatory processing” and continued practice of their art, secretaries (and perhaps others who practice physical tasks) are able to maintain performance (even if speed does decrease for some). Once again, control of voluntary movement may decline as people get older, but the causes are generally disease related (e.g., cerebrovascular accident, arthritis) or associated with disuse. One area of voluntary movement that does decline with age, for many, is postural control or occupational mobility. Nearly one third of people older than 65 fall every year, and falling even once increases the person’s risk of falling again.18 Falls are caused by many factors, both intrinsic and extrinsic. To improve safety, occupational therapy practitioners work to remediate the intrinsic factors that are amenable to intervention as well as to adapt to or compensate for extrinsic factors that cannot be fixed.20 Table 11-3 requires the reader to list potential intrinsic (within the person) and extrinsic (outside of the person) factors potentially causing decreased postural control. For example, an intrinsic factor leading to falls could be muscle weakness, and a potential extrinsic factor could be uneven floor surfaces in the client’s home. For each factor, think about how occupational therapy could help. TABLE 11-3 Factors Contributing to Fall Risk and Potential OT Interventions Sensory changes are inevitable. For example, visual changes generally lead to farsightedness, and a higher proportion of older people develop one of the diseases of the eye mentioned earlier. Sensory losses (especially if stimulation is not augmented through corrective measures [e.g., hearing aids, glasses] or replaced through another sensory system) can both lead to and be exacerbated by sensory deprivation in a sort of vicious cycle. The majority of older adults are likely to have one or more chronic conditions that can magnify the difficulties encountered because of sensory changes related to aging. In 1999, 82% of Medicare patients reported having at least one chronic condition, with 65% reporting multiple chronic conditions.49 Yet in spite of the sensory losses and the chronic health conditions that befall many older people, the majority, indeed the vast majority, manage to function in everyday life quite well. Older workers, when compared with younger workers, have a lower absentee rate, incur fewer workplace injuries, and are considered more dependable.37,39 Approximately 40% of those 65 and older report having a functional limitation affecting performance in everyday tasks (42% according to the Long-Term Care Insurance Sourcebook,33 and 38% according to the Administration on Aging2). Most of these reported limitations are in one or two ADLs (18%), whereas 5% reported problems with three or four ADLs, and 3% with five or six ADLs.33 Looking at these statistics as a glass half full or from a strengths, perspective, 71% of those 80 and older do not report needing assistance.2 The OTPF4 includes aspects of the client’s psychological character such as coping and behavioral regulation, body image, self-concept and self-esteem, and emotional stability. In considering the typical aging process, no major changes in psychological functioning or emotional regulation are expected. A few studies are notable and worth considering when working with older people; on the other hand, it is also worth noting that they offer general considerations and each individual may or may not fit into the expected trends. The long-term Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, which was instigated in 1958, found that as men age they tend to become more nurturing and more accepting of their feelings, whereas women tend to become more assertive and confident.22 Erikson proposed eight stages of human personality development, with the final stage being wisdom in old age, during which a person becomes more reflective and may even gain, in a sense, a better quality of life.50 With regard to the “big five” personality traits proposed by McCrae and Costa,34 there is evidence of both personality stability over time, with potential accentuation of inherent traits and ongoing development or change over time.6 For example, agreeableness and conscientiousness may increase into old age, whereas openness may tend to decline, especially after age 70.50 However, little is known about the differences of personality change among different ethnic and racial groups. Ardelt6 argues for the need to consider the context in which persons find themselves, including the social environment and life events that may bring about successful adaptation (resilience) or succumbing to stressful life events. When working with older people one has to consider that personal change and growth are possible and probable, and also that positive personality traits may be obscured by various events such as the influences of medication, pain, fear, and various medical procedures. Bandura11 has written extensively about locus of control, with people generally falling into one of two camps: those with an internal locus of control who believe they are masters of their own fate, and those with an external locus of control who believe they are merely pawns under the control of others (or fate). There are several domains of control: health, finances, transportation, friends, families, and living arrangements. One might expect that, as the number of chronic conditions increases and older people have less control over their living arrangements, the locus of control would become more external as people age. However, overall this has not been found to be the case. The diagnosis of depression rather than age is associated to a greater degree with a decreased sense of internal locus of control. High degrees of self-esteem and self-efficacy are associated with resiliency, or the ability to successfully cope with change. Resiliency is a personality trait considered to be a part of aging well.47 Those who are resilient in the face of losses tend to rate their health as better subjectively, be more independent in instrumental ADLs, and practice more health-promoting behaviors.50 Engaging in creative endeavors may increase resilience and have a positive, neuroprotective effect on the aging brain, according to a study by McFadden and Basting.36 This is important information for the profession of occupational therapy as we promote engagement in meaningful creative ventures as part of the therapeutic process. Quality of life is an overarching aspect of everyday living that also is expected to decline with age. As losses are incurred through an increasing number of conditions and decreased physical functioning (at least to a degree), one might assume that a general quality of life score would decline with age. Surprisingly, the opposite is true, resulting in what has been termed “the paradox of aging.”14 As people get older, they actually tend to rate their quality of life higher, if they have a minimum standard of living and are aging typically. Baltes and Baltes10 suggested that the reason may be “selective optimization with compensation” during which older people focus on those activities most important to them and learn to compensate for any loss of performance.

Analyzing the Effect of Aging on Occupations with an Emphasis on Cognition and Perception

Aging and Functional Performance

Client Factor (or Subfactor, Other Function, Trait, or Skill)

Examples

Occupational Example of What is Anticipated

Decreased short-term memory

Person forgets to take medications.

Slower movements

Person walks slowly and needs more time to do things.

Poor balance

Person falls more often.

Hard of hearing

Person has trouble hearing what is said.

Cognitive decline

Person gets confused easily.

Sensory changes

Person gets cold more easily or puts the heat up higher.

Senescent Changes

Sensory Changes

Macular degeneration, which particularly impairs central vision

Macular degeneration, which particularly impairs central vision

Glaucoma, which affects peripheral vision

Glaucoma, which affects peripheral vision

Cataracts, which decrease visual acuity

Cataracts, which decrease visual acuity

Diabetic retinopathy, which is associated with spotty and fluctuating vision

Diabetic retinopathy, which is associated with spotty and fluctuating vision

Area of Occupation: Specific Activity

Give an Example of How Anosmia or Hyposmia Can Affect This Activity

How Can Occupational Therapy Help?

ADL: Eating

Unable to notice foods that have spoiled.

Provide ways to date food, look for signs that it is bad. Provide labels for food.

IADL: Safety and emergency maintenance

Unable to smell fire or noxious gas.

Provide fire alarms and gas alarms. Ensure proper ventilation of rooms.

Physical Changes

Intrinsic Factors

How Can OT Intervention Help?

Muscle weakness

Increase muscle strength through engagement in valued occupations, including exercise if client desires.

Poor postural control

Provide core strengthening activities or external supports.

Poor coordination and timing

Increase coordination and timing; provide visual cues to assist client.

Visual perceptual

Provide cues to help client navigate; use assistive technology.

Extrinsic Factors

How Can OT Intervention Help?

Uneven floors

Provide home evaluation and education regarding safety in the home.

Barriers in the house

Remove barriers, provide hand rails if necessary.

Environmental hazards (i.e., wet, icy, and snowy surfaces)

Provide assistance removing environmental hazards; provide technology (e.g., railings, lifts).

Personality and Psychological Changes

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access