Adapted from Klasko, S., & Shea, G. (1999). The Phantom Stethoscope. Franklin, TN: Hillsboro Press.

Cultural differences are not new between the two groups. As a result, interdiscipline relationship problems and conflicts have been documented for at least the past 100 years. Power struggles between managers and physicians are historical. Management professors Margarete Arndt and Barbara Bigelow have combed through early 20th century articles from the American Hospital Association’s first journal, Modern Hospital, as part of their research. They found letters to the editor about problems with “difficult” physicians, and articles written by hospital leaders who reported business (financial) challenges caused by the hospital’s dependence on doctors for admissions, the costs of providing facilities and opportunities for physicians, and the ability of medical staff members to adversely influence public perceptions about hospital quality if the organization did not purchase technology that the doctor wanted for his use (2).

In more modern times, authors of healthcare books speak of problems caused in hospitals by inappropriate medical staff involvement in some hospital issues and lack of physician involvement in other, appropriate issues. Frontline staff have opinions about the relationship of administrators and doctors. Nurses have mentioned their perception to Kathy (our nurse Dyad author) that there is a general disdain that physicians feel for hospital administration. Klasko and Shea would probably not be surprised at these sentiments, as they note that neither physicians nor hospital leaders recognize that their views are culturally biased, and, because of this, each group judges members of the other group by their own norms (1).

Clinicians view managers as bureaucrats (sometimes helpful but often roadblocks to what the providers want to accomplish). Managers, while recognizing the importance of the clinical caregivers to the success of organizations, complain that some clinicians are “difficult to work with,” or describe them as being “not team players.” Members of both groups sometimes express feeling that individuals in the other group don’t respect them, are inflexible, and are more interested in the money to be made in healthcare than in providing the best possible care to patients. Each group wonders if members of the other group recognize the value of their expertise to the organization. Sometimes the actions or words of individual managers or clinicians reinforce these perceptions. Individuals who have had even a short career in healthcare have probably heard statements similar to the quotes gathered from our colleagues when we asked them to give examples of when they heard statements that they perceived as an indication of a lack of respect for particular roles (or former roles) in healthcare:

- “Don’t those administrators realize they wouldn’t have a hospital … or jobs … if it wasn’t for us?”

- “Those bureaucrats in the administration don’t know a thing about the real work we do in this hospital. All they know how to do is throw out red tape and make it hard to get anything done.”

- “Docs always say they are about ethics and what is best for patients. I think I’ll write a book about physician ethics. It will be 450 pages with only one thing printed on each page … a big dollar sign.”

- “No, I don’t want any physicians on the committee. We’ll waste all our time trying to educate them on the ramifications of what they think is best for this organization and why what they want to do is illegal or will cause us compliance problems.”

- “Oh, and I don’t want any nurses there either … they will waste our time talking about quality and staffing. This needs to be a business decision.”

- “Well, you know the problem with pharmacists is they all wanted to be doctors but didn’t have the smarts to get into medical school.”

- “One reason we have trouble with the hospital executives is that they were all the “C” students in school and we (physicians) were the “A” students. Of course we have trouble communicating.”

- “I really resent the big salaries those administrators rake in. They don’t make the money for this place. We physicians do.”

- “When I became a CEO, I stopped using my RN credential. You know, the other administrators just wouldn’t respect me as much if they were reminded that I was a nurse.”

- “These employed physicians want a say in how we manage? Don’t they realize they are employees? Employees don’t get to vote on everything we do!”

- “Don’t those doctors realize they wouldn’t have this hospital and the expensive equipment we provide if it wasn’t for us administrators?”

Of course, there are many professionals in every role who act and speak respectfully about other team members. However, traditional definitions of work and the greater community’s thoughts about that work has produced widely accepted stereotypes of individuals who perform different work in our society, along with beliefs about their intelligence and relative value to society. For example, the definition of a profession was once mainly limited to only three occupational fields: law, theology, and medicine. It’s only been in recent decades that other careers have been recognized as meeting the definition of a profession, which is “a field that requires extensive study and mastery of specialized knowledge, such as law, medicine, the military, nursing, the clergy, or engineering,” and which is “held by an individual who is usually licensed, is regulated by a quasi-governmental organization, must complete certain courses of education, pass further examinations, and are subject to disciplinary action, including revocation of a license” (3).

While who is designated as a professional may not seem significant today (when many career areas call themselves professions), this history of a premium label for only some members of the healthcare team has affected the collective consciousness about which work is “most significant.” It has also contributed to historical challenges to true teamwork among physicians, other clinicians, and “administrators.” It has the potential of making the development of true partnerships between healthcare leaders even more difficult, because change can occur only when people are willing to acknowledge that what may have been true in the past (i.e., only a few professions actually met the definition of a profession) or was perceived to be true in the past (those with higher education in one field are superior in all ways to those with lesser educations) is not absolute truth today.

Slightly derisive labeling (suits vs. coats) and philosophical arguments about who is a professional aside, there is another question for clinicians who choose formal leadership positions. Are they managers with a clinical background or clinicians with a management job? That question has more than one answer and differs for individuals both in how they identify themselves and how others describe them. For example, physicians who become managers or executives universally maintain “MD” or “DO” as part of their signature, expect to be called “Doctor,” and identify themselves as physicians, even if it has been decades since they performed any type of patient care. Nurses more often drop the “RN” immediately when they move into administrative roles that don’t require them to be an RN, such as COO or CEO positions. (Other clinicians, like pharmacists, who move into top roles seem to follow the same convention of “not advertising their clinical backgrounds” as the RNs). Without dwelling on the cultural, psychological, or societal reasons for this difference, it appears that physicians identify with their profession regardless of their particular job, are proud of their clinical background, and believe it is value added to their management/leadership role while many other clinicians do not.

The premise of this book is that both extensive clinical and business backgrounds/educations are essential for competent leadership of a healthcare organization. You will notice we did not say both are essential for a leader of a healthcare organization. It would be wonderful for an organization if it could boast of having individual leaders at every level who are interested in maintaining expertise in both the clinical and business world. However, as organizations enter the next era of healthcare, our very complex industry is becoming even more complicated, and there will be fewer individuals who can claim expertise in two specialties. (Peter Drucker has been widely credited with saying many years ago that healthcare is the most complex business of all. He should see us now!) Knowledge of two or more specialties is possible and preferable (a clinical leader needs an understanding of finance), but expertise (having as much financial education and knowledge as the CFO) is unlikely.

Leaders have always had to depend on their teams to supply expertise they lack, and the need for this will continue. In addition, some components of our new systems require leadership from both clinicians and business professionals. That’s why a variety of healthcare organizations are implementing a formal leadership structure referred to as Dyad Management.

A New Model for Leadership: The Dyad

Many leadership theorists and practitioners have recognized the values of teams in decision making and in accomplishing the work of the organization. Thompson and Strickland noted in 1999 (and organizations have only become more complex since then!) that this is true in all American organizations. They stated, “Not only are many strategic issues too big or complex for a single manager to handle, but they are often cross-functional and cross departmental in nature” (4). John Maxwell agrees in Teamwork 101. He says, “I assert that one is too small a number to achieve greatness. You cannot do anything of real value alone” (5). His writing is about teams in general, but the thoughts he expressed support the development of a leadership team model, such as the dyadic model of management.

Dyads are, as the name implies, mini-teams of two people who work together as coleaders of a specific system, division, clinical service line, or project. They may also consist of two leaders from different departments or service lines whose work is so interdependent that the organization’s goals can best be accomplished when they consistently and continually partner to meet those goals. Dyad management is a model of formal leadership in which two individuals with different skill sets, education, and backgrounds are paired to better fulfill the mission of the organization. The two partners have different job descriptions, and different duties that complement each other. When combined, their skills complete a set of management competencies needed for accomplishing particular clinical, business, and strategic goals of the organization. In the best pairings, the Dyad provides synergy. In other words, they create a team in which one leader plus one leader equals more than two leaders. By working together, Dyad partners can accomplish (along with their larger teams) what three or more managers accomplish working in individual silos.

Often (but not always) one Healthcare Dyad partner is a business and/or operations expert, and the other is a physician. The number of designated Dyads that includes a physician is growing because the model is recognized as a way for healthcare operations leaders and medical leaders to comanage a department, service line, or project. As the healthcare system evolves to meet the new world that is projected to constitute the next era of healthcare, the need for the business/operations side to merge with the clinical delivery side is intuitively superior to past models where there was greater (or at least perceived) division between them. Accountable care, bundled payments, pay for performance (or pay for value) all require operations/business leaders and physicians to work together on the development and implementation of new strategies. Both types of expertise are needed to work hand in hand for this to occur. A bonus to this new paradigm is that Dyad leadership increases the understanding of other team member’s contributions to the organization’s (and even other profession’s) success. Through these partnerships, organizations can begin to bring the two cultures (clinical and administrative) together to develop a blended culture for success in the new era. With new models of teamwork and Dyad management, there is an energy for development of new understanding of and respect for others.

In a permanent Dyad (identified on an enterprise’s organizational chart), one partner does not report to, or work for, the other. The boss–subordinate role implies that one profession is more important than the other, which perpetuates the age old perceived lack of (or at least lesser) respect for the skills of one of the leaders. It has the potential of setting up a less than open and transparent relationship between two people. (Whether we like to admit this or not, it is much more difficult to disagree with the person who evaluates you and has influence on your pay and future with the company. Respectful disagreement, or ability to openly state different thoughts on any issue, is important for the due diligence that all decisions should be subject to.) The success of the Dyad and of the organization requires a system that supports decision making that balances clinical and operational/business needs.

The partners often both report to the same executive, but in the increasingly matrixed world of healthcare systems, this might not be true. The essential tenet, wherever the individuals report, is that Dyad partners are perceived (and perceive themselves) to manage as equals. Even if the two partners report to different people, they should be positioned on the same level of the organizational chart. (If one reports to an executive VP, the other should report to an executive VP. If one reports to the CEO, the other should report to the CEO, etc.) Neither delegates to the other, because each has his or her own responsibilities for the management work they colead. However, each partner does have an accountability, not only to the organization but to the other Dyad partner, because they both “own” the department, service line, project, or other entity and have a shared responsibility for its success.

There is no limit to the variations of Dyad partnerships. Organizations can, and will, develop them to effectively work toward the accomplishment of the enterprise vision. Some examples of “permanent” Dyad partnerships (identified on the enterprise organization chart) include the following:

- A physician and nonphysician operations manager for a clinical service line (such as cardiology or oncology)

- The organization’s CMO and CNO

- A nursing manager (for the management of staff) and a clinical nurse leader (CNL) or advance practice nurse (APN) (for nursing clinical/nursing quality leadership of patient care) on an individual inpatient nursing unit

- The organization’s identified quality executive and the safety executive

- A physician and nurse comanaging an inpatient unit (critical care, orthopedics, etc.)

- A physician and nurse comanaging the organization’s perioperative services

- A physician and business manager comanaging an individual physician office or clinic

- The organization’s chief nursing informatics officer (CNIO) and chief medical informatics officer (CMIO)

The larger part of this book concerns these permanent Dyads. However, there are organizations that have found it to be effective to utilize temporary Dyad partnerships as a tactic for accomplishing projects that support their strategy. Examples of these types of “project” or “short-term Dyads” include the following:

- A nurse leader and a physician leader assigned to colead a building project for the company

- A nurse champion and a physician champion for a major change in the organization, such as implementation of evidence-based practices, installation of a new clinical information technology system, a new care model, or an LEAN process

- A nurse leader and a pharmacist leader to implement and enforce the appropriate use of bar-coding or smart pump technology

- A clinical leader and a financial leader to plan the clinical budget for a specified period of time or a particular set of goals

Whether the Dyad is permanent or temporary, the partners who make up this model of management are accountable to the organization as well as each other, to lead in a manner that honors the mission of the organization, supports advancement to the vision of the organization, and utilizes tactics that will fulfill both short- and long-term goals of the organization.

The mission of an enterprise is simply what the company seeks to provide, or do, for its customers. Mission statements are similar between healthcare organizations, although some are bigger or broader than others because of who the organization defines as its customers. The customers could be whole countries or communities or specific subsets of a population defined by criteria that segments individuals into groups that the organization serves.

Healthcare organizations do not have missions to “make money” (regardless of their for-profit or not-for-profit status), provide employment for healthcare providers (or anyone else), or serve as “workshops” for clinicians. They may do all of these things, but they are not the reason the organization exists.

The vision for the organization is where the enterprise is headed or wants to go. It is a picture of what its leaders (including the Board) see as its future. Strategy is the game plan for reaching that future. Tactics are the specific actions that managers utilize at every level in the organization to ensure that the goals that support the organizational strategy are being pursued and met. Dyad partners, like all organizational leaders, have a responsibility to understand the vision, contribute to strategy, and utilize tactics in pursuit of the organization’s goals.

As stated earlier in this chapter, the skills and responsibilities of Dyad partners will probably overlap, but they should not have identical job descriptions, and each should have identified primary accountabilities that are complementary to the other’s duties. In addition, when one leader has a primary role identified in his or her job description, this should not prevent the other partner from “stepping in” to help with that role. This can be tricky because it calls for exquisite communication skills and trust between the partners. The success of the Dyad depends on this.

An example of this need for complementary roles with specific accountabilities is the CMO and CNO Dyad partnership. The job description for the CMO may include a responsibility for leading all things involved with the practice of medicine across the continuum in the organization. The CNO’s job description will include leading all things involved with the practice of nursing across the continuum in the organization. Of course, medical care and nursing care cannot be that neatly divided; the two professions depend on each other, just as patients (or, in more modern parlance, the consumers of healthcare) depend on both professions. They overlap, which is why Dyad leadership is especially suited to these two positions.

When Dyads work well, their constituents (direct reports or members of the individual Dyad leader’s profession) feel comfortable approaching either Dyad leader for direction, advice, and guidance or to provide opinions and input to the leadership team. One example of this is when a physician has a concern about a new hospital policy or a medical best practice the organization is contemplating and just happens to run into the CNO before she sees the CMO. She can give her input to the CNO Dyad member, confident that the Dyad will consider it together. Conversely, a nurse who would like more information about a new nursing procedure should feel free to ask the CMO for assistance. When either the physician or nurse waits to speak to the leader of his or her profession, he or she is contributing to the “lack of nimbleness” frequently attributed to hospital leaders. Waiting to talk to someone from one’s own profession is undermining the ability of the Dyad to cover more ground and deliver on the promise that one plus one equals more than two.

This ability to back each other up requires regular, deliberate, and transparent communication between the Dyad partners. It requires each educating the other about his or her profession and informing the other about current profession-specific issues. It requires humility from each partner that allows him or her to realize that he or she doesn’t know what he or she doesn’t know. It requires a deliberate image campaign (discussed later in this book) that visibly demonstrates the partnership to all constituents and other stakeholders, such as patient populations and the community. It requires an understanding between the partners that each will strive to represent accurately the other’s thoughts and guidance to third parties. It requires trust that the partner respects and believes fully that this is a Dyad of Equals.

Traditional professional images (and, sometimes, gender images) present challenges to Dyads getting to equality. (Because the physician has traditionally been labeled the captain of the ship in patient care/clinical work, some assume he or she should also be the boss in operations and management/financial arenas even when he or she is the less experienced or educated manager.) However, there is another challenge that needs to be acknowledged and addressed in the development of successful, healthy Dyads. When one or both of the Dyad leaders is a clinician, his or her profession may have inculcated him or her with a conscious or unconscious disdain for the field of management. Conversely, a successful premanagement clinical career may have instilled a belief that formal leadership roles are a natural for people of advanced clinical skills, requiring no special education or preparation.

The latter conviction has caused problems in healthcare leadership for multiple decades. Many clinical leaders have been promoted into management positions because of their superior clinical skill. Unfortunately, because the skills of a clinician (even a leader in the provision of clinical interventions) are not the same as the skills of a manager, many fail to develop into superior leaders. Some fail and leave their formal leadership positions. Some succeed, but only after untold damage may have been inflicted on the organization or individuals while the new manager learned, by trial and error, his or her new (and foreign) role. Most frontline clinical leaders, regardless of clinical specialty, can relate horror stories from personal history with uneducated, untrained, or inexperienced managers. (Some can relate similar sagas even when managers were educated in management, but that is a competence issue, and is covered later.)

The study of management (with a brief history presented in Chapter 2) indicates that there are theories and research-supported best practices for those who occupy formal management positions. Like medicine, management is both an art and a science. Based on this, our premise is that clinical enterprise management is a specialty. A specialty requires specialized education, experience, and residencies (or on-the-job mentoring by an experienced professional manager.)

Acknowledgement that clinical management is a specialty helps explain many of the issues for which new clinical managers are not prepared. Clinicians beginning to practice a new specialty within their broader profession would never be expected to perform flawlessly, regardless of their previous competence in another specialty. For example, a physician whose specialty is medical cardiology could not perform cardiac surgery without additional training as a surgeon. A psychiatric nurse could not float to the operating room to scrub (or circulate) for an orthopedic surgical procedure without surgical nursing (and, even further, orthopedic surgical nursing!) specialty training. Yet clinical leaders are placed in management jobs without any management education (and then are criticized for making errors that experienced leaders consider basic “Management 101”) that even a brand new leader should have learned in school or along the way somewhere.

When organizations or individuals do not understand that management is a specialty, they are taking risks with the organization’s and individual’s success every time a clinician who is not prepared for the specialty of management is placed in a formal leadership position. Healthcare organizations are no exception. Outstanding medical or nursing care alone will not ensure that the organization will thrive or even survive. An enterprise needs competent leadership and competent management, too.

Leadership and Management

There has been quite a bit of discussion about the difference between leadership and management. Various academics, consultants, authors, and other “experts” have defined the two words with their own emphasis on differences between their meanings and their practical application. Some examples of management definitions are as follows:

- Management is the organization and coordination of the activities of a business in order to achieve defined objectives. Management consists of interlocking functions of creating corporate policy, and organizing, planning, controlling, and directing an organization’s resources in order to achieve the objectives (www.BusinessDictionary.com).

- Management is both an art and a science. It is the art of making people more effective than they would have been without you. The science is how you do that. There are four basic pillars: planning, organizing, directing, and monitoring (www.About.com/management).

- Management is achieving goals in a way that makes the best use of all resources (www.leadershipdirect.com).

- Management is, above all, a practice where art, science, and craft meet—Henry Mintzberg.

Leadership is usually defined with less granularity than management. It’s one of those elusive qualities that people just seem to know when they see it! However, many people have their own opinions of what leadership is. Some quotes on leadership come from well-known leaders:

- Leadership is the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because he wants to do it—Dwight Eisenhower.

- Leadership is intentional influence—Michael McKinney.

- Leadership is getting people to work for you when they are not obligated—Fred Smith.

- If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a leader—John Quincy Adams.

- Leaders conceive and articulate goals that lift people out of their petty preoccupations and unite the in pursuit of objectives worthy of their best efforts—John Gardner.

The difference between leadership and management has been defined by a variety of people, as well:

- Effective management is putting first things first. While leadership decides what “first things” are, it is management that puts them first, day by day, moment by moment. Management is a discipline, carrying it out—Steven Covey.

- Management is efficiency in climbing the ladder of success. Leadership determines whether the ladder is leaning against the right wall—Stephen Covey.

- In contrast to management, leadership is about influencing people to change (http://www.leadersdirect.com).

- Management is doing things right. Leadership is doing the right things—Peter Drucker.

If we simply accept Drucker’s definition of management versus leadership, we would be hard pressed to say which is most important to the long-term success of organizations. There seems to be a preference for being a leader, though. Each of us (authors) has met various people who work in healthcare who have proudly announced, “I am not a Manager. I am a Leader!” We can almost hear the slight sneer underlining manager in contrast to the pride of being a leader. We believe that both excellent leadership and excellent management are essential for the excellent organization.

Clinicians should be able to understand the difference and the importance of both doing the right thing and doing a thing right. A medical example that is currently making headlines in the United States comes from interventional cardiology. Some physicians have been accused of placing stents in patients who do not have a medical need for them. They are being censured for not doing the right thing, even if they flawlessly placed the stent. On the other hand, other clinicians might do a poor job of placing a stent that is medically indicated. From a patient’s point of view, which is more important? Would you say you received better care if you received an unnecessary intervention, done with great competence? Or would you prefer to need the stent and have the procedure done poorly (with adverse outcomes of some sort?)

The patient is better served by a physician who both does the right thing and does the thing right. Organizations are better served by people in power positions who both do the right thing (lead) and do things right (manage). In some situations, one individual is competent at both leadership and management. In Dyads, both partners should be leaders. At least one must be a professional manager. Dyad leadership is a model that supports the development of both leadership and management for a particular unit, program, service line, or project; because it leverages different skills of two leaders, and only one must be a management specialist. The other partner must have education and current knowledge about appropriate and competent performance of their professional specialty. In healthcare organizations, that partner is most often skilled in a clinical profession.

A strong Dyad has two leaders from different professional backgrounds who combine their experience and intelligence to make decisions about what is right to do. However, only one of the partners may be a professional manager, with the training, temperament, and experience that it takes to “do things right in an organization.” The other may not initially need to learn everything about “Management 101” because he or she brings more value to the Dyad by continuing to be an expert in his or her original professional specialty. For example, the physician member of a Dyad in healthcare today brings most value to the organization as the partner with medical, not management, expertise. He or she comes from the physician culture, which gives him or her credibility with medical colleagues along with knowledge of current best practice of medicine. (When he or she does have management experience and expertise, it is a bonus for the Dyad and the organization.)

Management 101: Doing Things Right

Either as a primarily business profession or as a specialty of a clinical profession, management is a field populated with individuals of varied skill. Anyone who has worked for more than one boss has determined that there are differences between the abilities of individuals who are positioned to manage projects or people. Some of these management variations may be due to perceptions of the formal leader’s charisma, or chemistry with people on his or her team. Others are due to very real variations in manager competency.

Clinicians understand that there are certain science-based core competencies that providers of care must possess to produce the best possible clinical outcomes for patients. There are also core competencies for managers. Some of these are the basics that make up the science side of management. Core competencies of management science include the ability to plan, organize, direct, and evaluate (or monitor) projects or ongoing operations.

Planning involves assessing a current state versus a desired state, setting a goal to reduce the gap between them, and then figuring out what resources are needed to accomplish that goal. Organizing is combining these resources in a way that will make the plan happen. Directing is telling people what to do. Evaluating is making sure they are following these directions in a way that ensures the plan is being carried out.

Plan, organize, direct, and evaluate—voila, you are a manager! How hard can that be, especially if you have been a successful clinician? The steps don’t sound all that different from the scientific method (based on the same steps used in research) learned in medical or nursing school and applied to the diagnosis and treatment of disease. This simplification of management to scientific competencies, of course, does not illustrate the total picture of this field, just as scientific knowledge (even when combined with technical proficiencies) does not constitute the total set of competencies for a clinician.

While the sciences of all three endeavors (research, medicine, and management) are similar, both clinicians and managers know that those who are really great at the practice of their respective crafts are also masters at the art of their profession, which is much more complex than the science. Art is the ability to use knowledge and specialty education in real-life situations. It is perfected with experience, involves creativity, and personal skill. Sometimes called the soft skills of a profession, the components of a professional’s art may seem intangible to those who are not members of that profession. That’s because it is much harder to describe, quantify, or prove than is science. Yet it is the art of each Dyad member’s specialty that brings the greatest value to this model of leadership.

It is art when a physician’s hunch results in a correct diagnosis that the evidence doesn’t make obvious. It is art when a nurse, consciously or subconsciously, is able to sense, feel, perceive, and know how to deliver the type of individualized care most likely to promote healing in his or her patient. It is art when a manager applies management theory and research differently in different situations. Since art is perfected with practice, it’s important that at least one member of the Dyad is an experienced, successful manager. In addition, part of his or her value-added expertise is knowing how to get things done in the organization, through an understanding of how the bureaucracy works, relationships with key organizational members, policies, and procedures.

In emerging healthcare Dyads, where a physician is partnered with a clinical operations professional or business manager, the nonphysician is usually the primary partner accountable for management of areas such as supply chain, human resources and labor, finance and budget, competition strategy and market share, the metrics, and performance scorecards. The physician partner is accountable for working closely with other physicians, with specific responsibilities such as managing physician productivity (particularly as this relates to the organization’s compensation model), establishing new models of care (such as medical homes or team-based care in primary care offices), managing physician driven use of resources, and decreasing inappropriate variation in physician clinical practice.

Both Dyad leaders are managers. They both need to do things right. To do things right requires communication skills, organizational knowledge, strategic thinking, and skill at implementing tactics. Each partner has different primary accountabilities, based on his or her expertise, experience, and influence derived from identification with a specific profession and culture. A Dyad’s influence on an organization, or individuals, is a combination of both partner’s influence on organizational stakeholders. In times of change, such as now, one of biggest benefits of Dyad leadership is this greater span of influence that comes from a leadership team with partners from two different professions and professional cultures.

Influence comes from power. Formal leaders in an organization have legitimate power, which means it is derived from the job and where it is positioned in the organizational hierarchy. Designated Dyad leaders have legitimate (or positional) power to perform their management work. They can hire, fire, and direct people to perform certain duties. In addition, each partner has personal power derived from expertise in his or her profession. Each has connection power as a result of networking with colleagues inside and outside the organization and information power based on knowing what is going on. One or both leaders may add referent power to the mix, a result of personal charisma that creates loyalty and admiration from others. In healthcare organizations, expertise, connection, information, and referent power can be closely tied to the leader’s profession and professional culture. So, it makes intuitive sense that power and influence of a Dyad team is multiplied when the two partners come from different professions.

Of course, the influence of the Dyad will not be effective if the two professionals do not come together as true partners or do not agree on their vision or goals. The promise of this type of leadership will only be fulfilled when this occurs, when the partners learn to lead together by doing the right things and to manage together by doing things right. The following chapters, along with stories about actual Dyad models and experiences are presented as a guide for leaders contemplating this type of leadership in their organizations and for potential and actual leaders who aspire to maximize the effectiveness of their unique partnership as a healthcare Dyad for the next era of healthcare.

Chapter Summary

The world of healthcare is becoming even more complex. As healthcare organizations move into the next era, leaders are implementing new management models. One of these, the Dyad, is envisioned as a way to manage complex systems while increasing partnerships between groups that have previously operated in silos. When two leaders are assigned to lead together each brings abilities and distinct competencies that complement the other’s skills. It is only when the partners respect each other as skilled professionals that they can learn to lead together.

Dyads in Action

The Dyad Leadership Model as a Strategic Initiative

The U.S. healthcare industry is experiencing an unprecedented sea change. The culprits behind this include the shifting demographics of the U.S. population, rising federal deficits, consumer demands for higher value, federal healthcare policies, an unsustainable appetite for new technologies, and general market dynamics caused by reduced third party payments. While the forces behind the change are not unique, response in today’s healthcare organizations appears to be very different from past experiences. Perhaps one of the most exciting results of this changing climate is the interest in adopting new delivery system models with physician alignment and clinical integration at the top of the priority list. Today’s healthcare organizations can either embrace this growing movement or they can take a “sit and wait” posture to see if these new emerging delivery system models actually succeed and make a difference in the long-term outlook and success for their organizations.

As we face these changing times with a different perspective, there is an opportunity to seize the moment and transform old models of working side by side, but not integrated, to true partnership. Mercy Medical Center in Des Moines, Iowa (MMC-DM), recognized the opportunity to change how it provides services by adopting a philosophy of integrating providers to redefine the delivery of its healthcare services. MMC-DM is one of several market-based organizations in Catholic Health Initiatives (CHI).

CHI is based in Englewood, Colorado; is one of the largest health systems in the U.S. MMC-DM, founded by the Sisters of Mercy in 1893; and is an 802-bed medical center providing a full range of services ranging from major tertiary care to primary care services. MMC-DM is composed of three hospital campuses, a highly integrated multispecialty clinic with more than 500 providers, and over 50 locations of physician clinics and outpatient care centers. MMC-DM operates an Accountable Care Organization with more than 100,000 enrolled members to date. MMC-DM is also a member of the Mercy Health Network, a multihospital network of 39 hospitals in Iowa operating under a Joint Operating Agreement between CHI and Catholic Health East/Trinity.

Industry at a Glance

The U.S. healthcare system is clearly taking on a different look today with growing regional and national health systems, the rapid fading of the private practice model, an increasing number of physicians aligned with and/or employed by healthcare systems, adoption of electronic medical records, and new partnerships emerging with historically competing organizations. Perhaps the general public believes these changes are the direct result of President Obama’s signature Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed in March 2010. We in the industry know the move to clinically integrated organizations and delivery systems was well underway long before the federal legislation took shape. In fact, the industry was under a self-imposed move toward integration based on the recognition that our traditionally fragmented healthcare system was not providing the value required by the Federal Government, commercial insurers, American businesses, or individual consumers. There was a clear recognition that the increasing cost of healthcare was unsustainable while, at the same time, the U.S. healthcare system ranked low in clinical outcomes and vital sign indicators when compared to other developed nations. As far back as the early 1980s, when the diagnostic-related grouping (DRG) payment methodology was implemented by Medicare to pay for inpatient care services, our healthcare leaders have been deploying new models of delivery systems and payment models. The passage of the ACA simply formalized and popularized the public spotlight on some of the changing models that were already under development. Regardless of the cause or need for change, one of the outcomes of this shift has been the coming together of historically separated parts of the healthcare system. The recognition and gradual fusion of physicians and hospitals working to become one clinically integrated delivery system has been an important operational and strategic step taken by numerous healthcare organizations. Alignment of providers has taken center stage for success for today’s healthcare systems, given the shared incentives emerging with the transformation of the healthcare system.

The Move to Dyad Leadership

One of the changes healthcare organizations have undertaken to prepare for the future is a new leadership model—the Physician Dyadic (Dyad) Leadership model. The “Dyad” assigns the dual responsibility to a physician and nonphysician leader, who assumes accountability for a clinical service, department, strategic initiative, or operating department within a healthcare organization’s structure for the entire organization. As the industry transforms to a shared and aligned operating agenda, the Dyad leadership model can be a complementary structural change to facilitate the development of an aligned organization. In its sociological roots, a Dyad can be defined as two persons involved in an ongoing relationship or intervention (6). As healthcare organizations embrace the opportunity for systemic change, the Dyad model is growing in popularity. We have all heard the old phrase, “a physician’s pen accounts for the majority of the cost of care.” Regardless of whether this is accurate or not, it is symbolic of the traditional model of care in which the physician directs the care provided to a patient while the hospital staff delivers the care based on a physician’s directions. It has also long been believed that this traditional payment model resulted in conflicting incentives between physicians and healthcare organizations, yet the new emerging model of accountable care and value-based payment systems are quickly fading any gap in incentives between physicians and healthcare organizations. The effective deployment of a Dyad leadership model in today’s healthcare organization can offer numerous benefits to drive the value agenda, while systemically creating an aligned culture for the organization to remove the separateness we have operated with in the past.

The Dyad Leadership Model Requires a Supportive Culture

While on the surface, it may seem simple to adopt a Dyad leadership model to assist an organization in navigating the churning waters of healthcare reform, it is clearly more than just a plug and play strategy. The effective emergence of a new leadership model requires a supportive culture to succeed. An organization’s culture can best be described as “how things really happen around here” or “the collective personality of the organization.” Regardless of the description of culture, it is imperative that an organization’s culture embrace the adoption of the Dyad leadership model. The culture needs to recognize the need for alignment and the shared physician role. It also must acknowledge the need for change to optimize the value of care, and service healthcare organizations must deliver to achieve accountable and cost-effective healthcare objectives.

Recognizing the culture imperative, MMC-DM’s board of directors, medical staff leaders, and administrative team implemented a “game changer” process to explore the best way to prepare for a new delivery system for the future. One of the most strategically and operationally important conclusions was the recommendation to adopt a Dyad Leadership Model in 2011. Essentially, MMC-DM understood the challenges of achieving a high-value delivery system using the traditional functional hierarchical and separated model of leadership and care delivery. To address both the challenge and opportunity to transform the organization’s operation and strategic direction, MMC-DM selected eight physician leaders to be paired with eight nonphysician leaders. These teams of two were designated to lead the organizations’ operational and strategic plans.

While MMC-DM was going through the “Game Changer” process, it was effectively shaping the culture to accept this change in the leadership model. For many years, MMC-DM maintained a vision for an aligned and integrated delivery system. It invested millions in developing an integrated multispecialty medical group to be relevant in an integrated model of care. MMC-DM had already initiated the path to an aligned future of physicians with the medical center through strategic initiatives for more than 20 years. The move to the Dyad was a natural extension of MMC-DM’s past philosophy to involve physicians in every possible area of the medical center’s operations. The culture at MMC-DM was ready to support the move to a Dyad in 2011. (As other healthcare organizations consider the Dyad model of leadership, it is very important that they assess the readiness of the culture before modifying the organization chart.)

The Path to Value-Based Care

The Dyad leadership model is also a prerequisite to truly building a higher value healthcare operation and system. There are numerous reasons why our healthcare system in the United States needs to move to a value-based healthcare system. Providers were historically paid for the volume of care provided; today’s move is to pay for value. The federal government’s Value-Based Performance (VBP) Program is a clear example of this transition. While we are likely in the early phase-in of moving to a completely value-based payment model, under the VBP, hospitals are subject to a loss of payment for inpatient care provided to Medicare beneficiaries based on performance for specific outcomes, patient experience, and process measures.

While the VBP is in a phased-in status, we can assume the healthcare payment system in the future will be almost entirely based on the value of the care and service provided. As a hospital executive, I have to ask: Why shouldn’t this be the case? We all, as consumers, use Internet-based search engines to find a value buy. In addition, based on tremendous variation and inconsistent clinical outcomes our traditional volume-based system has produced when compared to other industrialized nations, the move to a value-based system appears absolutely essential.

A value-based system of care design and delivery is completely complementary to the Dyad model. This is a topic of greatest interest and focus in our healthcare system today. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, in its November 2008 paper, From Volume to Value; Transforming Healthcare Payment and Delivery Systems, indicates that a major problem with the U.S. healthcare system is the payment system built to reward quantity of treatment, not the quality of care (7).

In addition, Oliver Wyman, a well-established global management firm, recently published a White Paper, The Volume to Value Revolution, in which it states that the U.S. healthcare system has not competed on value historically but that it is ready to change (8). Our literature is replete with papers and articles on the need to improve the value of our healthcare system in the United States. As the saying goes, we are perfectly positioned to get the results we are getting. If we are not achieving the value-based results we need in order to compete and sustain our missions, then we must address the structural changes needed to improve performance. Engaging and aligning physicians through a Dyad leadership model is the perfect structure change to achieve improved results and higher value outcomes. This opinion is backed up by statistics: a review of 300 top-ranking American hospitals found overall quality scores were about 25% higher when doctors ran the hospital compared to other hospitals (9).

The Affordable Care Act

The Dyad model of leadership has been used in some healthcare organizations for more than 25 years. Today’s adoption of the model seems to be growing with the trend toward integrated delivery systems and value-based and accountable care. These organizational changes preceded the passage of the Affordability Act, but they are certainly consistent with the broader goals to reform healthcare and improve value. President Obama signed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) into law on March 23, 2010. This sweeping legislation brought the debate on the organization and financing of healthcare in the United States into everyone’s living room, office, and locker room. While there continues to be open debate over the merit of the law and the likely chance for the successful attainment of the goals of the Act, it is now the law and we need to move to implement it accordingly.

MMC-DM’s strategic agenda to develop a highly integrated, high-quality, and cost-effective delivery system was in place long before the ACA, which provided some real head winds for us. Section III of the ACA: “Improving the Quality and Efficiency of Healthcare” is perhaps the most important and influential section of the ACA on the organization, delivery and financing of healthcare services. MMC-DM’s move to engage physicians in a Dyad model is directly consistent with the tenets of the Section III of the ACA. These include Transforming the Healthcare Delivery System, Linking Payment to Quality Outcomes, Hospital Value–Based Purchasing Program, and Medical Shared Savings Program.

These are just a few of the highlights of the key objectives under Section III of the ACA, but they certainly reinforce the need to actively engage physicians in the leadership of today’s healthcare organizations. We need our medical colleagues to help us achieve the objectives of transforming the healthcare marketplace while meeting the obligations of the ACA for providers. MMC-DM’s “Game Changers” were perfectly timed to seize the opportunity to restructure the organization for success in a rapidly changing environment.

Game Changer: From Theory to Practice

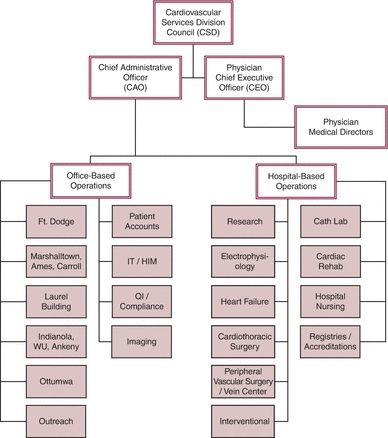

As previously mentioned, MMC-DM has a long history of physician alignment initiatives. In the early 1990s, we initiated two major Dyad models of leadership. These were established to lead two high volume, high impact clinical service lines. The first model emerged as a coleadership partnership for cardiovascular care. This was followed by the creation of a jointly led orthopedic specialty hospital arrangement. Figures 1-1 and 1-2 represent the organizational structures of MMC-DM’s two initial Dyad-led clinical service lines. In both cases, the system engaged and embraced a physician Dyad model to lead these important game changing initiatives.

FIGURE 1-1 Mercy Medical Center/Iowa Heart Center organizational chart.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree