CHAPTER 4 Amenorrhea

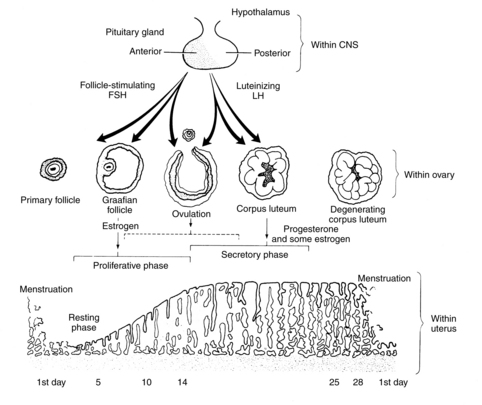

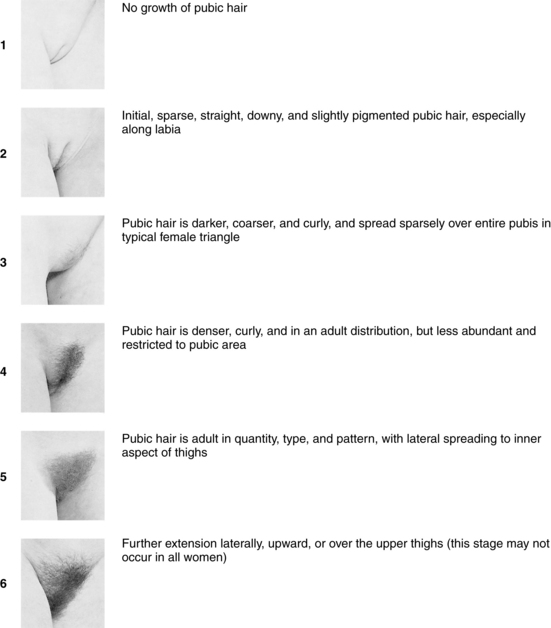

The normal menstrual cycle begins with the pulsatile delivery of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) by the medial-basal hypothalamus. In response, the posterior pituitary releases luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). These influence the growth and development of a follicle and its release of estradiol, which causes the uterine endometrium to proliferate and initiates the LH surge, which is followed by ovulation and menstruation (Figure 4-1 and Table 4-1).

Diagnostic reasoning: focused history

Pregnancy

For any female with a uterus, it is important to rule out pregnancy as the first step in determining the cause of amenorrhea. It is rare, but a young girl can become pregnant before the onset of menses. Pregnancy should be ruled out before the administration of androgenic challenge tests. If the woman is pregnant and there is accompanying bleeding, determination of whether the pregnancy is uterine or ectopic is the next priority (see Chapter 33). Be cognizant of domestic violence and sexual abuse, with consequent unintended pregnancy. Ask direct questions in private about being hit, pushed, or slapped or about having nonconsensual sex.

Seeking pregnancy

Is this primary or secondary amenorrhea?

Key questions

Have you ever had a menstrual cycle?

Have you ever had a menstrual cycle?

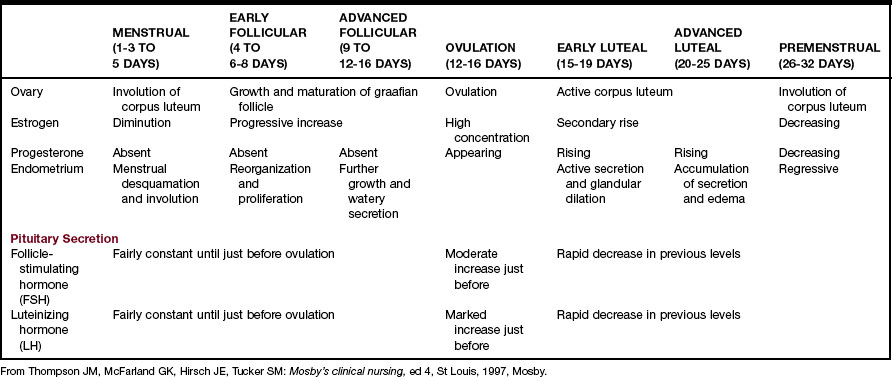

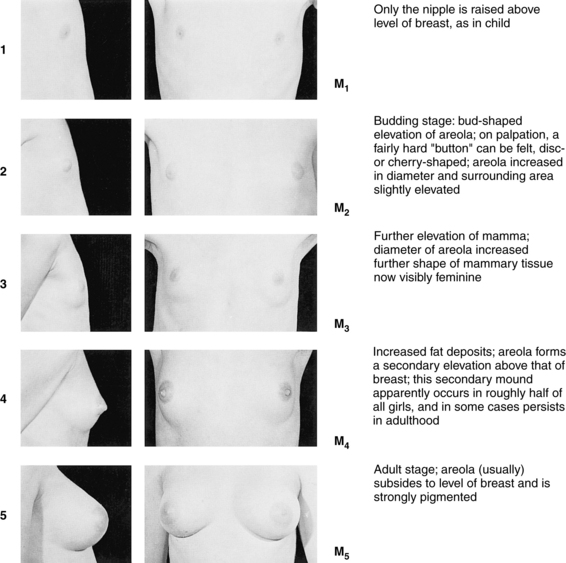

Have you started pubertal development? Can you show me how your breasts and pubic hair (PH) look compared with these pictures? (Use Tanner Sexual Maturity Rating [SMR] scales [Figures 4-2 and 4-3].)

Have you started pubertal development? Can you show me how your breasts and pubic hair (PH) look compared with these pictures? (Use Tanner Sexual Maturity Rating [SMR] scales [Figures 4-2 and 4-3].)

At what age did you start your periods?

At what age did you start your periods?

When was your last normal menstrual period?

When was your last normal menstrual period?

What is the nature of your periods (e.g., frequency, duration, amount of flow)?

What is the nature of your periods (e.g., frequency, duration, amount of flow)?

FIGURE 4-2 Five stages of breast development in females.

(Photographs from Van Wieringen JC, Wafelbakker F, Verbrugge HP, DeHass JH: Growth diagrams 1965 Netherlands: Second National Survey on 0-24-year-olds, Groningen, The Netherlands, 1971, Wolters-Noordhoff; reprinted by permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

FIGURE 4-3 Tanner sexual maturity development in females.

(Photographs from Van Wieringen JC, Wafelbakker F, Verbrugge HP, DeHass JH: Growth diagrams 1965 Netherlands: Second National Survey on 0-24-year-olds, Groningen, The Netherlands, 1971, Wolters-Noordhoff; reprinted by permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

Onset of menstruation

The age range for menarche in the United States is 9 to 17 years. If the woman has had established menses at intervals of every 21 to 38 days, then the classification of secondary amenorrhea would apply. Established menses indicate that there is no outlet flow problem and that the HPO axis and endometrium are functioning.

Pubertal development

A thorough review of pediatric growth charts is helpful in determining the young girl’s norm of growth and development and the centimeters attained by her latest growth spurt. Most adolescent girls have a mean height gain of 29 cm (11.4 inches) and the growth spurt lasts approximately 4 years. Asking adolescents to self-identify their Tanner SMR scales for breast and pubic maturity provides very accurate staging (see Figures 4-2 and 4-3). Additionally, it gives the opportunity for insight into their feelings about their body and self-esteem.

Age of menarche

The lack of menstrual periods and secondary sex characteristics by age 14 or the lack of menses by age 16 in the presence of secondary sex characteristics is considered primary amenorrhea. Fifty-six percent of all adolescents start menses when PH development is at PH stage 4 and 19% at PH stage 3 (see Figure 4-3). If the adolescent is PH stage 4 but has not had a menses, then primary amenorrhea should be diagnosed. However, if the adolescent does not meet the age and maturation criteria, then suspect she is experiencing delayed puberty or is a so-called “late bloomer.” She is likely to have a family history in her mother and sisters of delayed menarche. Almost 80% of amenorrheic adolescents with intact female genitalia and developed breasts have an inappropriate LH feedback, anovulatory cycles, or high levels of androgenic hormones. They will bleed after a PCT and should be monitored for continued menses to avoid endometrial hyperplasia.

Energy and bowel changes

Increased functioning of the thyroid causes restlessness and diarrhea, whereas decreased functioning results in constipation and fatigue. Even mild thyroid dysfunction can cause menstrual irregularities; therefore a thyroid function test is needed to assess the thyroid status.

Galactorrhea

Women notice breast nipple discharge that is not associated with breastfeeding or medications. Offensive medications are listed in Box 4-1 and include primarily the dopamine antagonist agents and estrogens.

Box 4-1 Drugs That May Cause Amenorrhea

Prolactin increase

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree