7. Altered body image and the surgical patient

Adèle Atkinson and Rosie Pudner

CHAPTER CONTENTS

What is meant by body image?91

Perceptions of altered body image92

Reactions to altered body image93

Conclusion100

At the end of the chapter the reader should be able to:

• discuss the meaning of body image and altered body image

• discuss perceptions of body image

• discuss the effects of surgery on body image

• identify the effects of altered body image on body reality, body presentation and body ideal

• discuss social support and coping strategies

• highlight the role of the surgical nurse in supporting the patient with an altered body image.

Introduction

The importance of physical appearance as an aspect of identity is very closely allied with the notion of who we are as people. Body image carries significant meaning, and is consistent with self-concept, self-esteem and identity. The very nature of surgery is a traumatic invasion upon the body and the self, and will invariably cause temporary or permanent changes. Some of these changes may not be anticipated or only emerge after the patient has been discharged. The issue of altered body image, and the degree to which it might affect patients’ quality of life and self-concept, has become an increasingly important factor to consider when caring for patients undergoing surgery. This chapter will predominantly discuss issues related to patients undergoing planned/elective surgery, but will highlight issues related to patients undergoing emergency surgical procedures where appropriate.

What is meant by body image?

Body image is a widely used but poorly defined term. The concept of body image is generally taken to include the psychological and social aspects of behaviour. At the simplest level, body image has been described as how we think and feel about our bodies (Schilder, 1935 cited in Price, 1990a). It is also believed to be the perception and evaluation of one’s physical functioning and appearance (Fisher and Cleveland, 1958). Other authors have emphasized the dynamic and ever-changing nature of body image and the external changes that can alter perceptions of body image (Hobza et al., 2007, Janelli, 1986, Price, 1990b and Salter, 1997).

Physical appearance and behaviour are influenced by society, and the predominant sociocultural values of youth, physical attractiveness, health and wholeness are constantly reinforced through the media and by social contact. Evidence from studies of the psychology of person perception indicates that, regardless of other variables such as sex, age, intelligence and class, the physically attractive are favoured over others across a wide range of situations (Clifford and Walster, 1973, Dion et al., 1972 and Tiggemann et al., 2007).

Further evidence has shown that perceptions and feelings about body size, function and appearance are also included in body image and have an impact on levels of self-esteem (Price, 1990a). This means that body image is a psychological experience focusing on conscious and unconscious attitudes and feelings. There is no single static image of the body, as it is always in the process of revision, being shaped according to the current situation of the individual.

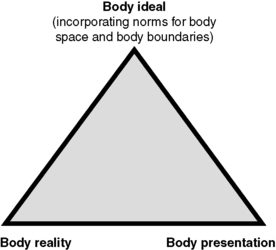

Price (1990b) identified three major aspects of body image which, when in balance, constitute a healthy body image and a sense of well-being (Fig. 7.1). These three components are described as:

• body reality, i.e. the physical body as it is

• body ideal, i.e. the individual’s desired body image

• body presentation, i.e. the body as it is presented to the world.

|

| Figure 7.1 • A body image model. |

Most people will have experienced dissatisfaction in all areas at one time or another due to the natural consequences of their genetic make-up, or the processes of physical maturation, ageing or other environmental events which cause changes in body image and subsequently in self-concept. It is also suggested that body image is the root of our identity, self-esteem and self-worth, and thus the basis from which man functions (Wassner, 1982).

The influence of body image on personal self-image is an easier concept to comprehend, as it suggests that self-image is built upon valuing the opinions and respect of others and that body image is used in society to negotiate and develop a sense of self-worth. Views on what constitutes the ‘self’ are the subject of endless debate, but perhaps it is fair to say that self-image is our own assessment of our social worth and is important for our self-confidence, motivation and sense of achievement (Price, 1990a).

Perceptions of altered body image

Body image perceptions adapt to the naturally changing events in life such as puberty, pregnancy and ageing. However, unpredictable or unavoidable changes to body image, such as those that can occur due to the trauma of surgery, sometimes precipitate long-term consequences. These may alter perceptions of body presentation and consequently self-image.

Body image is a very personal matter and depends upon the experiences and the adaptability of the individual. Mind and body are closely linked together, so that what happens to the body can have an effect on emotional health and vice versa. It can also determine a person’s behaviour, as a result of the effect on self-concept. If people are not feeling well, they may not take as much care with their personal appearance, e.g. not washing hair, not wearing make-up or not shaving. This has the effect that when people look at themselves in the mirror their physical appearance reinforces how they feel. Since body image disturbance is the state in which an individual experiences a disruption in the way in which the body is perceived, it could be assumed that the consequences of surgery might have an effect on that individual’s quality of life. At the same time, the individual may have to come to terms with the fact that the surgery is not a question of choice and that the treatment can be as bad as the disease, e.g. formation of a stoma following removal of a bowel tumour.

Certain operations can arouse specific fears in addition to the fear of pain and even the threat to life – e.g. mastectomy, formation of an ileostomy, colostomy or urostomy, amputation and certain types of plastic surgery – where fears of mutilation can be highly stressful. These fears can be related to the consequences of the change in daily life, and thus the perceived alteration of a concept of self.

Both the concept and the psychological effects of altered body image have been well studied, particularly in relation to the more obvious states of illness or injury, such as from the perspectives of oncology, burns, stomas, mastectomy, orthodontics and skin diseases (Elcoat, 1986, Goin, 1982, Kelly, 1987, Newton and Gursharan, 2005 and Salter, 1997).

Changes that occur as a result of the surgical procedure, such as the insertion of a wound drain or intravenous infusion, may cause a disruption in body image; thus, a holistic approach to care should always consider the issue of altered body image as an integral part of a person’s well-being. The nurse is in a unique position to engage the patient in conversation while caring for them, seeking in these dialogues to re-examine the meaning, if any, of altered body image and its impact on the patient. Perceptions of damaged or altered body image, and thus self-image, may significantly affect the patient’s rehabilitation. This presupposes that health professionals are fully aware of the many meanings that changes in body image could have for the patient, the burdens that are carried by the individual and the factors that affect those burdens.

The individual interpretations of a person’s experiences are concerned with perceptions and behaviours. Nurses need to help patients to cope with their reactions to the effects of surgery, and, since nurses are involved in determining patient needs, it is important that they have an insight not only into the obvious but also into the less obvious aspects of psychological perceptions. For example, in some situations a small scar may cause a patient more anxiety than a larger scar. Altered body image is therefore defined by the patient and not by health professionals.

Assessment of the perceived effects of altered body image is also complex because of the subjective nature of the phenomenon of body image. The nurse may have had some experience in reviewing her own body image, as well as the nature of body image in general, as she will have been exposed to caring for others who have suffered physical trauma or who are dying. These experiences usually give a greater insight and empathy with the patient.

Reactions to altered body image

Being a patient in hospital and requiring assistance with any acts of daily living has been identified as a threat to body image, because of the changes in body presentation and the body ideal (Webb, 1985). How a person responds when faced with changes in body image depends on many factors. These are mainly bound up with their personality and the way in which that person perceives and values their own body, and their ability to adapt to stress. It also depends on the nature of the change to their body image, how it was brought about, and whether the change is visible, prominent, or hidden as in the case of a woman having a hysterectomy. This may involve making adjustments for the future or it could be life threatening. The significance of this change in body image may impact on the person’s work, social or sex life and be perceived to have a negative effect on their future lifestyle. However, there are some patients who do not perceive a change in body image as a threatening disability or a problem, and this should be recognized by the nurse. It should therefore not be an assumption that the surgical patient will interpret a change in body image in a negative fashion.

Cultural issues are also associated with body image, and need to be taken into consideration when caring for patients from different cultures. Dewing (1989) identified the sexual connotations related to the breast in Western society, and that women undergoing a mastectomy may no longer feel attractive to their partner and alter the clothes they would normally wear. Smith (1997) highlights the fact that a change in body image can affect patients as to how they are seen by their family members and the community they live/work in. The ethnic background of the patient may also create anxieties with body image: e.g. risk of keloid scarring in the Afro-Caribbean population. Religious faith can also impact on body image: e.g. for those patients who follow the Sikh faith, it is paramount for the body to remain intact. This could therefore create a problem if a man had to undergo an emergency circumcision for paraphimosis. Patients who practise the Islamic faith may experience difficulties if they have a stoma, as they are not permitted to perform ablutions during prayer times (Smith, 1997). This may cause problems for the patient if his stoma works within the confines of the mosque, and the potential risk of this occurring may prevent the patient from attending the mosque.

Surgery on specific parts of the body also impacts on body image. Wounds resulting from surgery on the breast, uterus or genitalia can have significant meaning for women, as it is connected to their reproductive functions, while surgery on the male genitalia links to reproduction and sexual prowess. Women may see the surgery as a loss of their feminity and a loss of body ideal, while men undergoing prostatic surgery or an orchidectomy may fear impotence and loss of their manhood, also affecting their body ideal.

Breast surgery, either a lumpectomy or mastectomy, changes the shape of the breast and so affects body reality (Keeton and McAloon, 2002), and may impact on the woman’s role in society. For Chinese or Vietnamese women, especially if they are of child-bearing age where in traditional Chinese medicine the breast is important in breastfeeding, a damaged breast means an outward sign of inner turmoil. There may also be an associated feeling of shame and the woman may withdraw from an intimate relationship with her partner/husband (Smith, 1997). In Western society, much emphasis is put on the shape and size of the perfect breast, so a change in shape or size following breast surgery can cause psychological trauma in some women.

If patients have a stoma formed – either temporary or permanent – it is a violation of body integrity (Borwell, 1997) and can threaten the patient’s self-esteem. It may alter their position in their social/cultural community and may lead to a life of isolation; separation from their family in relation to cooking, eating and caring; and preclusion from their place of worship. In some instances, they may be seen as permanently unclean and untouchable. A Chinese woman with a stoma may even withdraw from public life, as the stoma is seen as unhealthiness in the person (Smith, 1997).

The face is also extremely important. This is because the face equates with attractiveness, so surgery to the face may alter the patient’s perception of their attractiveness (Berscheid and Gangestad, 1982). If surgery to the face interferes with eating or talking, then this may further reinforce feelings of unattractiveness and helplessness.

Amputation of a limb not only alters body image but also extends it, as a prosthesis has to be worn and crutches, a walking stick or wheelchair may be used to get around. The manner in which patients construct meaning out of the experience will affect their attitude and concordance to wearing the prosthesis (Desmond and MacLachlan, 2002).

Hidden body image changes should not be forgotten, as these may also impact on the patient. This may include gynaecological surgery, or loss of fertility following hysterectomy. Also, areas of skin normally covered by clothing are more likely to be exposed in the summer months and when undertaking certain sporting activities such as swimming. A patient with a scar on the top of the arm may not want to expose it and prefer to wear short-sleeved tops rather than sleeveless tops, or a scar on the top of the leg may mean that a man will not wear shorts.

However, if there is conflict, and anxiety exists as a result of an altered body image, the nurse is well placed to recognize reactions, which are often manifested in the form of a grief response (Kubler-Ross, 1969 and Parkes, 1972). Some surgical procedures may make a person look or feel ‘different’, presenting a major challenge. Patients may grieve for the loss of their ‘old’ body image and this is particularly exacerbated for the patient with a stoma, amputation or any mutilating surgery. However, this is not just limited to individuals with a visibly altered body image, as many patients may grieve for less obvious losses, such as changes in relationships, lifestyle and loss of personal freedom. A woman may have a sense of loss following a hysterectomy, as she may feel that she has lost her feminity. Likewise, a man may have a sense of loss following an orchidectomy, as he may feel that his masculinity and sexual prowess have been affected by the surgery.

Loss of body image causes a grief reaction which will release in the afflicted person feelings of insecurity, particularly if the person perceives the change as a crisis. Tension and depression are typical reactions, and their recognition is the key to understanding the person’s stress, sometimes perceived by the health team as being out of proportion to the magnitude of the actual surgical event. Yet, grief, loss and mourning are all terms which have been associated with changes in body image, regardless of the cause, and can continue long after the patient has been discharged.

Bereavement may also be encountered by patients with an altered body image, and Dewing (1989) identified the following four stages of bereavement:

1. Impact – the initial shock and anger which can precipitate depression and pessimism regarding recovery. This reaction is exacerbated by those patients who have experienced sudden traumatic changes in body image and have had little or no time to receive information about, or prepare themselves for, the implications of the surgery, e.g. patients undergoing emergency surgery.

2. Retreat – a phase of mourning for the affected part and a desire to return to the previous self. There is often denial, avoidance and emotional withdrawal.

4. Reconstruction – recognition of implications, accepting the use of aids and planning for the future.

Coping mechanisms are often employed unconsciously and are a normal human reaction to control fear and anxiety. A crisis associated with body image might be revealed by certain types of behavioural defence mechanisms which have been observed by Wright (1986) (Box 7.1). Adjustment can be enhanced by the nurse with the appropriate skills to care for patients with an altered body image.

Box 7.1

Box 7.1 Types of behavioural defence mechanisms

• Passivity. A change of mood or affect which can lead to sadness or withdrawal. The patient does not wish to be involved with their own care and may feel they are unacceptable. Motivation is poor and there is a loss of purpose and initiative.

• Denial. The patient refuses to look at or touch the altered part and may even deny its absence, trying to carry on as before. This dissociation from changes in body image demonstrates a distortion of reality which is a clear sign of psychological disequilibrium. The therapeutic relationship may be threatened by this resistance.

• Reassurance. The patient persistently seeks attention to check that they are still acceptable, sometimes making self-denigrating remarks to initiate a compliment. This can be a powerful affirmation that a person’s attraction does not depend on a wholesome body reality.

• Isolation. This may be self-imposed because the patient feels unacceptable and fears risking rejection.

• Hostility. This may be due to a strong protest about what has been perpetrated on that person. It can also be a manifestation of anger against the medical profession and is often associated with grief and loss.

Source: Wright (1986).

Regardless of the cause of altered body image, it is argued that patients who have had a sudden traumatic change, e.g. following emergency surgery, may experience greater difficulty in coming to terms with the perception of loss, and will need more time to accept the event and their feelings regarding it (O’Brien, 1980). If a person can discuss – and, more importantly, be allowed to discuss – the fears and anxieties of forthcoming surgical procedures, it can promote healthier coping mechanisms and better reintegration of body image. The introduction of preadmission and preassessment clinics provides a place where this can be facilitated. It has also been identified by Price, 1990a and Salter, 1997 that support networks are also important in helping patients to adapt to a change in body image.

The preoperative phase

The prospect of imminent surgery and its hidden consequences naturally causes a considerable amount of fear for the patient. The preoperative phase is a time when the nurse can discuss the patients’ fears and anxieties and the events that are likely to occur during their hospital stay, and patients are able to express any concerns regarding a change in their body image. An important piece of research which had an impact on nursing practice focused on giving information about the physical experiences that may be expected following surgery, with the result that postoperative pain was generally found to be reduced (Hayward, 1975). Boore (1978) also found that giving patients information preoperatively about their future care and treatment reduced stress in patients postoperatively. As this will reduce the amount of circulating adrenaline (epinephrine), pain should therefore be reduced. However, if a patient is admitted for emergency surgery, there is limited time for this to occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access