SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

• Precursors to aggression

• Factors that inhibit aggression

• Clients who may be liable to aggressive expression

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

• Methods to minimize the risk of aggression and violent incidents

• Ways to manage an aggressive client or incident

• Management following an aggressive incident

• How nursing care can minimize the incidence of aggression

• Methods to limit the incidence of aggression and violence in the working situation

PROFESSIONAL AND ETHICAL KNOWLEDGE

• Legal issues concerning nurses, clients and the workplace

• Zero tolerance for aggression

PERSONAL AND REFLECTIVE KNOWLEDGE

• Become aware of your own aggressive responses

• Become aware of your own precipitants to aggression

• Apply the principles of aggression management to professional nursing practice in all branches of nursing

INTRODUCTION

This chapter addresses the topic of aggression and how nurses respond to this danger. It does this by explaining aggression from its theoretical and practical aspects. An important feature of this chapter is the application of the concepts that are discussed to nursing practice.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

This part of the chapter examines the term aggression and the situations where it occurs. The main focus of this section is on biological and psychological explanations of aggression.

Care delivery knowledge

This section addresses how to manage aggression. Models of aggression management are discussed and applied to clinical practice. Aggression management and methods to reduce the aggressive actions are key elements of this section.

Professional and ethical knowledge

Here there is a discussion of the professional issues that stem from aggression. This includes those arising from the management of aggression as well as legal, preventive and safety concerns.

Personal and reflective knowledge

Within this section is an extended exercise for you to complete, to increase awareness of your own responses to aggression and to provide you with evidence for your learning portfolio. In addition, this section contains four case studies (pp. 288–289) that explore issues of aggression management in each of the four branches of nursing. You may find it helpful to read one of them before you start the chapter and use it as a focus for your reflections while reading.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

AGGRESSION AND VIOLENCE IN HEALTHCARE

Aggression is any form of behaviour used with the intention to harm or injure another person (Health Services Advisory Committee 1997). This includes acts carried out with the intent to cause physical harm, directed either outwardly towards others or inwardly at the individual (self-mutilation). They range from verbal or emotional acts to serious physical harm (Shepherd 1994). This includes antisocial behaviour, for example lack of respect towards others; physical or verbal aggression where the intent is to injure; and assault with the intent being to cause the other person harm.

Bibby (1995) defined health-related aggressive actions as those occurring when a health worker feels threatened or abused or is assaulted by a member of the public during the course of their duties. Similarly the Counter Fraud and Security Management Service, a special health authority within the NHS who have overall responsibility for the management of violence and aggression within the healthcare sector, define aggression as: ‘the intentional application of force to the person, without lawful justification, resulting in physical injury or personal discomfort’ (CFSMS 2006).

These definitions however, fail to take into account unintentional violence resulting from illness or injury, or where a patient’s mental capacity is impaired. Whatever definition of aggression is used, it should have meaning for those involved, and show recognition of the problem encountered as part of their work. Promoting the issue of violence and aggression within the healthcare setting is as important as defining it, if not more so.

Nurses frequently deal with people who are in desperate need of attention and care, which they may, through ill-health, age or other circumstances, be unable to provide for themselves. They work with people across the whole of society, in circumstances that may be difficult and demanding, and often work long and unsociable hours. Patients may be anxious and worried about coming into hospital and what might happen to them. Some may be predisposed towards violence and aggression as a means of coping. Likewise, it may be that their relatives or friends express frustration or distress through aggression. While these factors do not excuse aggression, it is understandable why nurses and those that they care for occasionally come into conflict. It is important to recognize at this point that aggression is very rarely purposeless. People are aggressive either because they want something to happen or because they want something to stop happening. In clinical settings, aggression and violence may be used by patients as a way of getting what they want. Violent acts may be used to force change or to gain control. Rewards from violence include attention from staff and status and prestige among the patient group. For example, the patient who behaves violently is observed more frequently and has more opportunities to discuss concerns with their doctor and nursing staff. Despite this nurses are often expected to face their assailants and even to continue to provide and care for them following an attack. This situation is likely to test the nurse’s ability to cope with the psychological consequences of threats and assaults even further, and the cycle can become self-perpetuating.

Aggressive actions can also originate from colleagues. Many tensions can occur within work teams and in healthy organizational cultures; those tensions can be a valuable force for initiating change. Psychological violence is often perpetrated through repeated behaviour, of a type which may alone be relatively minor but which cumulatively can become a very serious form of violence. Although a single incident can suffice, psychological violence often consists of repeated, unwelcome, unreciprocated and imposed actions, which may have a devastating effect on their target. This is typical in bullying and harassment. Bullying turns to harassment when it is targeted repeatedly toward the same person or staff group and the chosen target is to some extent defenceless in the face of the perpetrator.

Bullying is a real problem within the health service, causing many staff to take sickness absence or early retirement and to leave the service altogether. Most organizations now have polices and procedures for dealing with bullying and harassment that outline what is and what is not acceptable behaviour. Penalties for transgression can result in dismissal. However, proving someone has been a bully is difficult, particularly if it has been done in a covert way.

The Evolve 12.1 resource provides further information on bullying in the workplace.

It would be wrong to rely solely on policies and procedures to protect the individual from aggression. One possible way of combating aggression such as bullying is to develop skills of assertiveness (RCN 2005). It is suggested that those people who are singled out for bullying and harassment are those that lack the ability to stand up for themselves and their rights. Linsley (2006) suggests that assertiveness is about the individual standing up for their rights in such a way as not to violate the rights of others. Being assertive can help the individual to develop a belief and confidence in herself or himself. The more that individuals stand up for their rights and act in a manner that is respectful of themselves and others, the higher their self-esteem. Assertiveness consequently can help a person to develop their self-confidence so that they can address threatening situations effectively.

THE VULNERABLE ADULT

A vulnerable adult is someone who, because of mental or other disability, age or illness, relies on the help and services of others in order to meet their needs. At times this can bring them into conflict with those that care for them, and in some cases this leads to conflict, exploitation and abuse. This is a growing area of concern and one that warrants the attention that it is only now getting.

Vulnerable adults may be abused by a wide range of people including relatives and family members, professional staff, paid care workers, volunteers, other service users, neighbours and friends. Abuse may be physical or psychological. It may simply be neglect or it may occur if the vulnerable person is forced to enter into an exploitative financial or sexual transaction to which he/she has not consented or cannot consent (Department of Health 2000).

When considering physical abuse it is important to consider the nature of the injury and whether this is in keeping with the history given. This should be balanced against what you know and observe of the patient; as in so many cases of abuse, the first real indicator is a change in the behaviour of the person.

Indicators of sexual abuse may include, along with changes in behaviour, bruising and bleeding around the sexual organs, and changes in personal hygiene, such as, wetting, soiling and a reluctance to undress.

Emotional abuse might result in the person becoming withdrawn; this can include physical changes such as weight loss and lack of sleep. The person might become watchful of others and their demeanour may change when a certain person is present. The abused may become withdrawn and lose interest in themselves and their surroundings.

Discriminatory abuse is perhaps one of the hardest forms of abuse to accept as it is perpetrated, sometimes through ignorance, by the very people who are meant to care. A lack of respect and a substandard level of service can be as emotionally and psychologically damaging as physical abuse. Denying a person the right to be involved in their own care; excluding them from opportunities such as health, education, employment and housing; explaining behaviour and medical symptoms solely in terms of the person’s disability; viewing people on the grounds of race, culture, age and gender are further examples of this type of abuse.

The protection of adults raises a variety of complex issues; however, staff have a duty to report suspicions or disclosures made about any abuse. It is important to record events at the time they happened, with clarity and dispassion, separating fact from opinion. Other information should include: where and when the incident took place; if there were any witnesses; what was said and observed; what action was taken, if any. It is important that the member of staff report any concerns they have immediately to prevent further abuse occurring. The Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act 2000 introduces a new vetting and barring scheme for those who work with children and vulnerable adults (Department of Health 2006). At the heart of the scheme is the provision of a register that lists those that have been banned from working with vulnerable groups having neglected or otherwise harmed individuals in their care.

All trusts and voluntary agencies have policies on reporting abuse which should be in accordance with good practice and standards. Unfortunately though, many incidents and near misses go unreported (Ferns & Chojnacha 2005).

For further information see Evolve 12.2.

ABUSE OF CHILDREN

As with adult abuse, child abuse may consist of a single act or repeated acts. The abuse can be physical, sexual, emotional and/or psychological. If a child confides that they may have been abused, the following is advised (HM Government 2006):

• Remain calm, approachable and receptive.

• Listen carefully without interrupting.

• Make it clear that you are taking him/her seriously.

• Acknowledge how difficult this may be.

• Let him/her know you will do everything you can to help him/her.

• Report on as per local policy.

What to avoid:

• Do not let any shock or distaste show.

• Do not probe (it is not your job to investigate but report).

• Do not suggest in any way to the child what may have happened. On occasions this may be done inadvertently by asking a leading question.

• Do not speculate or make assumptions.

• Do not make any negative comments about the alleged abuser.

• Do not make any promises you cannot keep.

• Do not promise to keep the information secret.

It is the responsibility of all staff to safeguard the welfare and well-being of those they look after and work with by protecting them from physical, emotional and sexual abuse, harm or neglect and supporting them if this occurs.

WHY AGGRESSION HAPPENS

Many theories of aggression have been developed, which suggests that there are many different causes of aggression. Each has its support and its criticism but although there is no unanimously accepted explanation, each theory helps to develop insight into the build up and display of aggression.

BIOLOGICAL THEORIES OF AGGRESSION

Biological theories focus upon somatic phenomena underpinning aggression. Three major theories are examined in this section: the role of neurotransmitters, the endocrine system and genetic influences.

Neurotransmitters

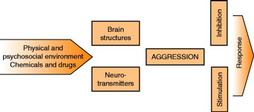

Two neurotransmitters, noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and serotonin, have been the prime focus of studies into aggression. Low serum concentrations of serotonin and high serum noradrenaline concentrations have been found in aggressive individuals (Hollin 1992). Unfortunately, though, a simple cause and effect relationship between these neurotransmitters and aggression has not in fact been found. So, while they do not cause aggression on their own, they may contribute to the severity of the aggressive episode (McElliskem 2004) (Fig. 12.1).

The endocrine system

Most research into hormones and the aggressive response has concerned the sex hormones. These are thought to act at two levels:

• First, by predisposing the individual to become biologically developed in terms of muscular and other body systems to enable aggression to be used in the pursuit of sexual or other drives.

• Second, by the direct incitement to act aggressively under the influence of sexual hormones.

Owens & Ashcroft (1985) were among the first to note how the male sex hormone, androgen, influenced aggressive responses. They discussed how castrated rats became less aggressive – probably due to their removed androgen supply – and how monkeys with high serum androgen concentrations were associated with higher levels of aggressive responses. The problem is that it is difficult to replicate these findings in human subjects. Although it can be shown that males are more involved in violent and sexual crimes and that male delinquency is associated with the onset of puberty (Beresford et al 2006), attributing such behaviour to high androgen levels has not been proven in human subjects.

One other area of hormonal influence on aggressive behaviour is the role of hormones in the menstrual cycle (Hines & Kimberly 2003). This was promoted by women attributing violent or aggressive actions to the premenstrual stage of their menstrual cycle. Again problems establishing a definite causal linkage is the major issue and as yet this has not been established.

Genetic factors

Whilst the exact amount of influence that genetics have on aggressive behaviour is still questioned, studies on animals have shown that a tendency towards aggression is at least partly inherited. The main problem with biological research into aggressive behaviour is that it is difficult to separate factors like genetic make-up from the complex variables that make up human individuals.

Consequently, while biological theories throw an interesting light on the nature and severity of aggression, to adhere strictly to a biological causation of aggression is unsafe. Aggressive behaviour always occurs within a social context and it is this factor that must also be examined.

PSYCHOSOCIAL THEORIES OF AGGRESSION

The psychoanalytic theory

Freud’s model of the person comprised a bipolar model (Frankl 1990):

• At one pole is an Eros drive – the instinct for life.

• At the other pole is a Thanatos drive – the death or destructive instinct.

The assumption behind this theory is that two primitive forces, the life and death instincts, oppose each other in our subconscious, and this incongruence is the origin of aggression. Freud asserted that this is a process void of thought patterns and is driven entirely by our instincts. This model would seem to have a crucial flaw, however; having defined the general aims of the life and death instincts, Freud failed to determine their source.

Frustration–aggression hypothesis

The frustration–aggression hypothesis was first set out in the 1930s by Dollard et al (1939). It proposes that aggression, rather than occurring spontaneously, is a response to the frustration of some goal-directed behaviour by an outside source. Goals may include such basic needs as food, water, sleep, sex, love and recognition. Contributions to frustration–aggression research further established that an environmental stimulus must produce not just frustration but anger in order for aggression to follow (e.g. Berkowitz, 1990 and Geen, 2001), and that the anger can be the result of stimuli other than frustrating situations, such as verbal abuse (Cohen et al 1998). Anger will always lead to aggression, however, as anger can be displayed in a number of ways and conversely act as a motivator and medium for positive change (Berkowitz 2001).

Social learning theory

Social learning theory focuses on aggression as a learned behaviour. It analyses the roles of models (a behaviour displayed by another) in the acquisition of aggressive behaviour (e.g. Anderson and Dill, 2000, Freedman, 2002 and Akert et al., 2005).

Social learning has three principal components:

1 Behaviour: an observer sees a model perform a particular behaviour.

2 Learning or acquisition phase: the observer attends to important features of the behaviour, remembering what was seen and done.

3 Performance: imitates the behaviour at a later time.

Children learn many social skills through this process. It involves being attentive to the following: remembering, imitating and being rewarded by people, television, books and magazines (Bushman 1998). Reducing restraints on aggressive behaviour through modelling thus can in turn reduce the inhibitions against behaving aggressively by leading a person to believe that this is a typical or permissible way of solving problems or attaining goals, and in turn, distort their views about conflict resolution (Bushman, 1995, Bushman, 1998 and Geen, 2001).

The role of anger

While anger frequently precedes violent behaviour, it is important to recognize that anger does not always lead to violence. Anger is a negative emotion that arises when there is a threat or delay in achieving a goal, or a conflict between goals. It signals that something is wrong in oneself, in others, or in one’s relationship(s) with others and the three possible targets of a person’s anger are others, impersonal objects/life conditions, or oneself.

Sometimes it may be therapeutic to legitimize anger, perhaps if the standard of healthcare falls below what the individual expects. In fact, many people believe that anger is healthy and necessary. Hollinworth et al (2005) suggest that it is a common experience to become angry, and that expressing anger is a normal process. It is not the anger that is legitimate and right, but the stress that underlies the anger. Expressing anger is also a mechanism for enhancing self-respect, and a constructive action that can lead to correcting a perceived wrong.

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

THE NATURE OF AGGRESSION

Aggression takes many different forms. Physical aggression inflicts harm through deed or act, whereas verbal aggression creates harm through words. Aggression can also be expressed directly or indirectly (Kaukiainen et al 2001). Direct means of aggression take place in face-to-face situations, whereas indirect aggression is delivered via the negative reactions of others (Buss 1995). Often, indirect aggression is a kind of social manipulation, like spreading malicious rumours about the target person or trying to persuade others not to associate with him or her. Bullying and harassment are two types of aggression commonly found in the workplace (Royal College of Nursing 2001) which encompass this type of behaviour. Not only are such behaviours upsetting for those directly involved, but also for those who witness and have to deal with it.

As we have seen, aggression means different things to different people. Make a list of behaviours that you associate with aggression using the following headings:

Words and phrases

Behaviour

Moods and emotions

Body language.

• Which of these behaviours do you attribute to yourself?

• Which of these behaviours do you attribute to others?

• Are there similarities between the two lists?

MINIMIZING THE RISK OF AGGRESSION

Perhaps the biggest cause of aggression is interpersonal provocation (Berkowitz, 1993 and Geen, 2001). Provocations include insults, slights, other forms of verbal aggression, physical aggression and interference with an individual’s attempts to attain an important goal.

In some cases, the nature of a person’s job might include multiple risk factors. Social workers provide an example of an occupation in which organizational, social and political factors can be found, including (Health and Safety Executive 2004):

• Allocation of scarce resources.

• Compulsory admission of some mentally ill and mentally impaired people to hospital.

• Removal of children from some homes against the wishes of the parents.

• Investigation of cases of non-accidental injury to children.

• Compulsory removal of some elderly people from home to hospital.

• Supervision in the community of men and women with a history of potential or actual violence, some with an associated mental disorder.

Violence and aggression then result as much from the characteristics of the healthcare worker and the organization in which they work as from the characteristics of the individual.

See also Table 12.1 and Table 12.2.

| Prediction category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Personality factors | Low threshold of frustration or impulsivity Increased liability to become aroused An antisocial personality such as someone who is habitually aggressive or undercontrolled Substance abusers |

| Previous history of aggression or violence | An institutional record where violence has been a factor may mean an increased risk of violence A genetic constitution that tends towards a lack of control |

| Biological factors | Disinhibitory factors such as caused by brain damage, and some organic mental illnesses |

| Mental disorder | Psychotic individuals who experience a build-up of tension before a violent outburst Some depressed individuals may attempt to kill others for altruistic reasons, to relieve their supposed suffering Frustration, fear or pain may lead to aggressive responses |

| Prediction category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Peer influences and group pressures | Peer and group pressures to act aggressively may be exerted on individuals Certain geographical areas may process more aggressive cues than others School influences can occur with some schools processing relatively more offenders in their pupils compared with other schools Generally, the cultures that individuals may have been exposed to that do not denigrate aggression may predispose certain individuals to an aggressive response pattern |

| Economic, social and environmental influences | Economic and social deprivation tend to be associated with offending and sometimes aggressive responses There may be an association between situational influences and aggressive behaviour, such as the availability of weapons Additional social factors include extrafamilial roles, peer group and media influences Uncomfortable or stressful social or physical conditions can predispose to aggression |

| The presence of a victim | As a subject upon whom aggression is expressed is necessary, so victims are essential in the expression of aggression; the assertion is made here that aggression is not likely to occur without the presence of someone on whom to carry out the aggressive act |

IDENTIFYING CUES THAT WARN OF IMMINENT AGGRESSION

At times, for whatever reason, interventions between service users and care staff go wrong. When this occurs, there are three possible types of outcome. The conflict may be resolved peacefully and may even result in positive learning and action; the conflict may be left unresolved and perhaps cause greater trouble at a later stage; or the conflict may escalate and result in some form of aggressive behaviour. Aggression places both clients and staff at risk, so it is essential that interventions are made before this occurs (DiMartino et al 2003).

Behaviour is the first warning of impending aggression in others. Box 12.1 lists a series of behaviours that are associated with aggression.

Box 12.1

Motor agitation

Increased restlessness and an inability to sit still and concentrate

Rapid movement and change of position

Appearing tense

Foot tapping

Leg swinging

Departure from usual or previous posture

Increased respirations

Grinding of jaw

Sudden loss of colour

Closing hand to make a fist

Thumping fist or slapping hand on another object

Picking up objects

Pacing

Verbalizations

Verbal threats

Intrusive demands for attention

Pitch and volume changes

Shouting or muttering

Significant changes in the pace of speech delivery

Abrupt replies especially if accompanied by gesticulations

Speech directed in ‘general’ and not at individual

Evidence of delusional or paranoid thought content

Name calling, swearing or being deliberately provocative

Affect

Anger

Hostility

Noisiness increases generally

Sudden or unnatural quiet

Feeling of heightened tension

Level of consciousness

Confusion

Sudden change in mental health status

Disorientation

Memory impairment

Inability to be redirected

Staff may ignore such signals owing to a lack of confidence in their own skills to deal with the situation and fear that they could make matters worse rather than better. Unfortunately, avoidance of potential aggression is likely to increase the danger. Consequently, an awareness of the escalation of aggression is essential. Once the danger signals are recognized, limiting action can be taken, and there is consequently a greater probability of a satisfactory outcome.

Describe factors in each of the following that may contribute to the potential for violence and aggression in a care setting and identify how each might be addressed in your area of work:

• A client or their relatives/friends.

• A member of staff.

• The work environment.

• Event(s), e.g. keeping a client waiting too long.

WAYS TO MANAGE AN AGGRESSIVE INCIDENT

Responding to violence and aggression

One of the major challenges facing modern health services is responding to violence and aggression but unfortunately there is no simple answer to the problem. During the last 10–15 years there have been a variety of strategies and recommendations, both from government agencies and experts in the management of violence; these have had varying degrees of success. Empirical research into the effectiveness of such actions is lacking and consequently there is confusion as to what constitutes best practice. It is difficult to predict exactly how someone will respond when faced with the threat of violence and aggression. For many staff their choice of response could greatly determine the safety not just of themselves but of everyone involved, and profoundly affect their relationship with those that they care for.

The immediate response to an aggressive incident

Personal safety is priority. Professional codes of conduct do not require individuals to jeopardize their own safety; it is better to leave and find an alternative safer way of containing the situation. If there is no choice but to intervene, however, as would happen if you were unable to remove yourself and needed to defend yourself, colleagues should be alerted via a panic button, call system, emergency telephone or panic alarm. Similarly, bystanders should be asked to leave the area and move to a place of safety.

Containing an aggressive incident: the assault cycle

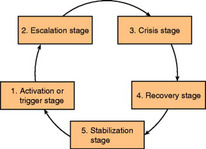

If the point has been reached where an aggressive act is imminent, then the assault cycle is entered (Fig. 12.2). Using this model helps to identify how the aggression has occurred and the type of intervention that would be most appropriate.

|

| Figure 12.2 |

Activation or trigger stage

In this stage some event or interpersonal situation arouses the person. It could be as the result of one thing or an accumulation of things.

Judith woke up late for her morning shift. She went to the kitchen for coffee and breakfast and found that she had run out of milk. Hungry, she left the house, intending to buy a snack from the local shop, only to find when she arrived that she had forgotten her purse. As she could not do without her purse she had to return to her house to collect it. She was now very late and became entangled in morning traffic. Arriving late for work someone said the ‘wrong thing’ to her and she responded by ‘biting their head off!’

Referring to the fight or flight response and the effect of hassles (see Ch. 9, ‘stress, relaxation and rest’), offer a possible explanation for Judith’s reaction.

Escalation stage

Stress and frustration increase and calming interventions need to be used. Feelings, emotions, attitudes and posture all influence the way that people view and listen to each other. Explaining something to someone who is feeling upset, angry or indignant is difficult until the person’s feelings have been relieved. Consequently, the person’s feelings need to be recognized and acknowledged. A return to calm remains possible at this stage though and this should be the aim. However, in areas of low support, such as working in the community, the practitioner should aim to extract themselves from this situation and to return to base.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access