Chapter 15 Ageing and Health Breakdown

When you have completed this chapter you will be able to

INTRODUCTION

THE AGEING POPULATION

Australia and New Zealand, along with the rest of the world, have ageing populations. People are living longer than ever before due to various factors, including improved health services, and scientific and medical developments that have led to improvements in pharmacology as well as other technologies that promote longevity. In addition, increasing consumerism has resulted in an enhanced awareness of the role of diet, exercise and general health maintenance among people in general, including older people. These factors, coupled with a declining birth rate, mean that Australia’s population will continue to age at least until the middle of the century1. From a health perspective, people are considered old once they are 65 years and old, old when over 85 years.

TERMINOLOGY

The branch of medicine concerned with the elderly is called geriatric medicine, or gerontology. Geriatrics is a word derived from the Greek word geras, meaning old age2. Gerontology is also derived from Greek (geron = old man) and is the umbrella term used to describe the study of ageing and its problems, and encompasses biophysiologic as well as social and psychological aspects2. More recently, the term gerontic nursing has become part of the health care lexicon and is a broad term to describe the range of caring acts associated with nursing older people2.

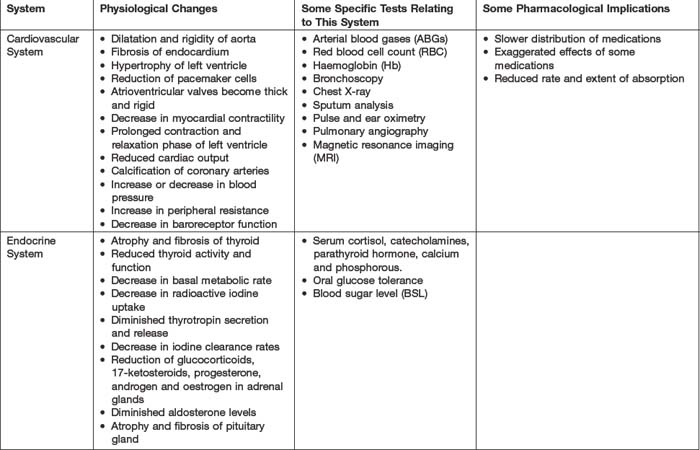

SYSTEMIC CHANGES ASSOCIATED WITH AGEING

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

The cardiovascular system is the system most likely to deteriorate as people age3. Structural changes may include dilation and increased rigidity of the aorta3,4, fibrosis of the endocardium5, left ventricle hypertrophy4, and thickening and rigidity of the atrioventicular valves5. There may be loss of pacemaker cells and an increase in fibrosis and adipose tissue both in and around the heart4,5. Rigidity of the aorta and ventricle walls leads to a decrease in myocardial contractility3. There is a decrease in the amount of blood filling the heart and therefore in the amount that is pumped out with each beat (reduced stroke volume)4. In older people, the contraction and relaxation phase of the left ventricle are prolonged, resulting in reduction of the heart’s pumping ability3,4,6 and reduced cardiac output3. There may be calcification of the coronary arteries that impedes blood flow and causes hypertrophy of the left ventricle4.

As people age, changes in the lining of blood vessels frequently occur. The middle layer of the vessel, tunica media, becomes rigid due to the thinning and calcification of the elastin fibres. Fibrosis and an accumulation of fats and lipids lead to atherosclerosis in the inner layer, tunica intima6. Some common examples of health breakdown in the elderly due to age-related changes in the cardiovascular system include atherosclerosis, and hypertension or hypotension.

ENDOCRINE SYSTEM

In the endocrine system, there are many diverse changes that can be attributed to ageing6. Structural changes include fibrosis and atrophy of glands and an increase in nodularity4,6. These changes may lead to a decrease in activity, basal metabolic rate, and less thyrotropin secretion and release. There may be a decrease in iodine clearance rates4,6, excretion of 17-ketosteroids and thyroid function due to a loss of adrenal function6.

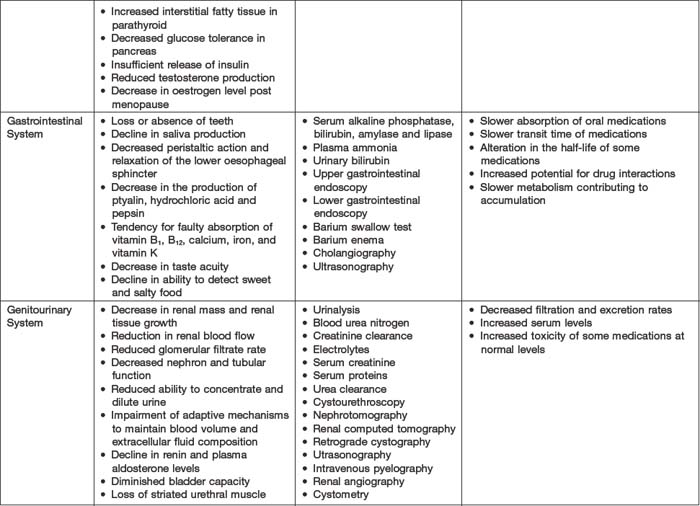

Secretion of glucocorticoids, progesterone, androgen, oestrogen and aldosterone are all reduced6. The volume of the pituitary gland decreases6, there is atrophy and fibrosis, and a decrease in vascularity, mass and weight. There is increased interstitial fatty tissue in the parathyroid gland4. Age-related changes to the pancreas lead to a decrease in glucose tolerance4 and insufficient release of insulin by the beta cells leads to a decrease in the older person’s ability to metabolise carbohydrates6.

GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

Problems associated with the gastrointestinal system are common in older people7. Changes in function include decreased gastric emptying and increased gastric pH8, decreased peristaltic action of the oesophagus, reduction in the production of ptyalin, hydrochloric acid and pepsin and a tendency for faulty absorption of vitamins B1, B12, K, calcium and iron9. Many older people experience poor appetite10; which may be due to a reduction in taste bud acuity and a decline in their ability to detect sweet and salty food10. Older people can also experience problems with their dentition6 which decreases their ability to enjoy eating. Impaired swallowing increases with age11 and has been attributed to decreased salivation to moisten food5,6. This may also be due to medications such as antihistamines and antidepressants that have anticholinergic effects11. Their gag reflex may be diminished resulting in dysphagia6 and nearly half the people aged over 80 years have diverticulitis due to weakening of the intestinal wall12. Other physiological changes include a tendency to constipation or faecal incontinence. The latter is caused by loss of muscle tone of the internal sphincter of the large intestine and diminished awareness of a forthcoming bowel evacuation9.

GENITOURINARY SYSTEM

A number of structural changes of the genitourinary system occur as people age. Within the kidneys, renal mass4,6, renal tissue growth, renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate decrease and creatinine clearance falls with age6. Tubular reabsorption and renal concentrating ability decline, resulting in less efficient tubular exchange of substances, conservation of water and sodium and antidiuretic hormone secretion. Adaptive mechanisms to maintain blood volume and extracellular fluid composition are impaired as people get older and plasma renin and plasma aldosterone levels decrease4. In the bladder, smooth muscle is replaced by fibrous connective tissue, the muscles weaken and bladder capacity decreases4,6. There may also be loss of striated muscle in the external urethral sphincter and decrease in closing pressure4. Older people may experience decrease in the force of the flow of urine4,6, difficulty in bladder emptying and delay in micturition reflex3,4,6.

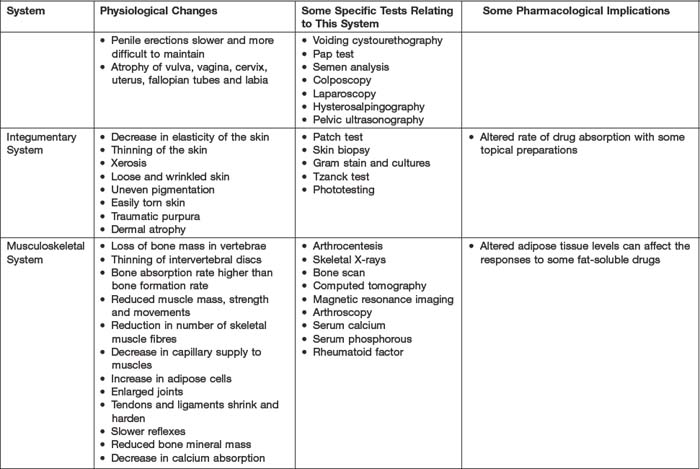

In older men, fibrosis of seminiferous tubules can occur, as well as reduced fluid retaining capacity in the seminal vesicles6, and erections may be slower and more difficult to maintain4. The prostate enlarges with age3,5 and testosterone production may be reduced6. In ageing women, a decrease in eostrogen levels weakens the skeletal pelvic floor muscles and urethra smooth muscle3,5. There may be atrophy of the vulva, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes and labia, and the vagina may atrophy and shorten with thinning of the mucous lining and loss of elasticity6.

Age-related health breakdown related to the genitourinary system includes urinary incontinence, benign prostatic hypertrophy and urinary tract infection3,4,5,6.

INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM

The older person’s skin differs significantly from the skin of a younger person13. Reduction in skeletal muscle mass and subcutaneous fat leads to loose, wrinkled and fragile skin8. Skin elasticity is reduced12 and the time taken for an older person’s wounds to heal is usually longer due to reduction in epidermal turnover and repair14. Sweat and oil secreting glands atrophy and the older persons’ skin loses its ability to retain moisture and is likely to become dry and scaly15. Cellular changes can range from uneven pigmentation16 through to the development of malignant melanoma14. Nearly half the people aged 65–75 years of age have at least one significant skin problem, and the majority of people over 75 have between one and four disorders12. These include pruritis (severe itching), lentigos (liver spots), eczema, purpura, seborrheic keratoses12, fungal infections and other skin disorders such as scabies and herpes zoster17.

MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

As a consequence of the ageing process, there is decreased bone and muscle mass, and muscle weakness6. Older people’s bones become brittle due to reduction in calcium absorption6 and because the rate of bone reabsorption is greater than the rate of new bone formation4,5. The number of skeletal muscle fibres decreases with age3,4,5,6 and there can often be atrophy and decrease in muscle fibre size3,4,6. Older people may experience a decrease in height due to a loss of bone mass in the vertebrae and thinning of the intervertebral discs4,5,6. Joints may become enlarged6 and tendons and ligaments can shrink and harden, resulting in reduction of joint mobility3. In addition, synovial fluid in the joints can become more viscous and membranes more fibrotic6. Reflexes become slower, largely due to shrinkage of muscles and tendons4.

Age-related alterations to the musculoskeletal system can lead to changed appearance and slower movements in the older person4. As a consequence of these changes, their movement is often more cautious, they may experience difficulty maintaining their balance3, and can be prone to falls6. Three examples of health breakdown due to changes in the musculoskeletal system are osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and fractures.

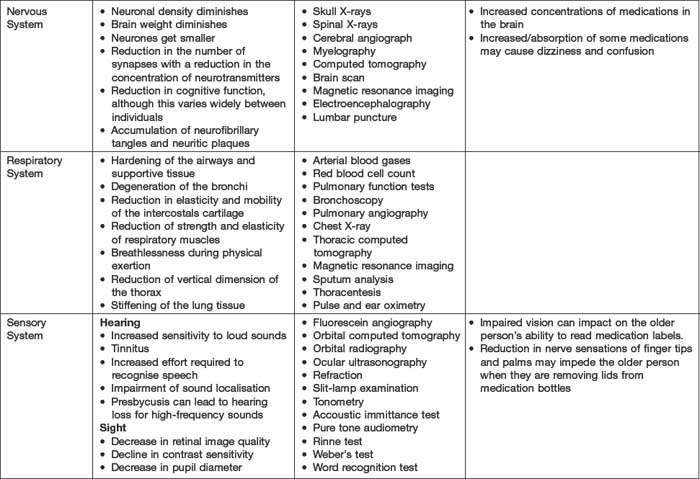

NERVOUS SYSTEM

Nervous system changes attributed to ageing are diminished brain weight18, and a reduction in the size and density of neurones19. The number of synapses is reduced, as well as the concentration of neurotransmitters7,19. As the body ages, there may be an accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques associated with dementia20, and cognitive function can diminish, although this varies widely between individuals21. It is important to remember that one way in which older people’s cognitive function can be maintained is by presenting them with interesting and challenging learning activities15. Alterations in normal sleep patterns can occur with age, and the older person may experience increased wakefulness and arousal from sleep8. Some examples of health breakdown associated with the ageing nervous system are dementia, delirium, depression, insomnia, epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease17.

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

Respiratory function is affected by advancing age14. Hardening of the airways and supportive tissue can occur, and degeneration of the bronchi, reduction in the elasticity and mobility of intercostal cartilage, and reduction in the strength and elasticity of the respiratory muscles are common9. Pulmonary function tests are likely to reveal a decrease in vital capacity and reduction in forced expiratory volume8. Older people may be unable to take deep breaths, have decreased cough reflex and dry mucous membranes4. Respiratory disorders common in the elderly are asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia and influenza17.

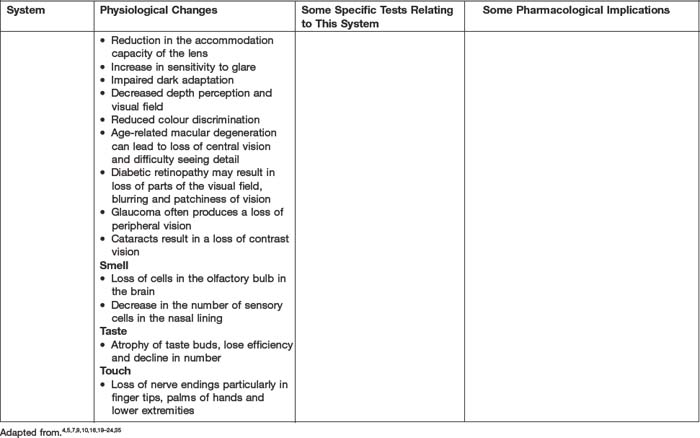

SENSORY SYSTEM

As people age, the acuity of the five senses, hearing, sight, smell, taste and touch, tends to diminish7.

Disorders associated with the ageing eye are macular degeneration27, which can lead to loss of central vision and difficulty seeing detail, and diabetic retinopathy, which may result in loss of parts of the visual field, blurring and patchiness of vision. Glaucoma often produces a loss of peripheral vision24, and cataracts result in blurred vision, sensitivity to bright light and changes in colour vision15. Vision impairment can impact negatively on the older person’s ability to interact with others, and may lead to functional difficulties, loss of independence, social isolation, loneliness and decreased quality of life27.

PHARMACOLOGY

Pharmacokinetics may be affected in older people and this is due to systemic changes affecting drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (see Table 15.1). Altered pharmacokinetics are attributable to age-related changes, such as decreased cellular activity, reduced blood flow to major organs, decreased renal and hepatic function, reduced gastric motility, decreased muscle activity, and altered homeostatic responses30.

Older people are vulnerable to polypharmacy31,32, a phenomenon that has been linked to health problems as diverse as constipation33 and delirium34. There are various definitions of polypharmacy. Galbraith, Bullock and Manius35 state that it is ‘the excessive or unnecessary use of medications’. Patel36 takes a different view and defines it as the use of multiple medications by an individual that can cause drug-to-drug interactions, and links it to the presence of multiple disease processes. Older people tend to have more health problems both in number and complexity than younger people37, and so have legitimate reasons for increased drug use.

Hayes37 asserts that polypharmacy accounts for 30% of hospital admissions of older people. It is of vital importance therefore that clinicians have an awareness of existing medication intake before prescribing or administering a new agent. In some situations, an individual’s health status is such that a risk/benefit analysis will support the introduction of a new agent, despite any known hazards associated with concurrent use of certain agents. The responsibility then is on clinical staff to be aware of the nature of the possible reactions, and to monitor older people closely and regularly for any evidence of the presence of adverse reactions.

Many pharmaceutical agents have adverse affects that may compromise the general health of older people and it is important that nurses maintain a sound knowledge of the adverse reactions of commonly prescribed drugs. Consider oral health as an example; many prescribed drugs have the potential to cause xerostomia (dry mouth), reduced salivary secretion, ulceration and/or discolouration of the oral mucosa, oral pain and swelling, oral infections and altered taste sensations31. Any or all of these adverse affects have the capacity to contribute to difficulties with appetite and food intake, and, therefore, compromise nutritional status. Sometimes, additional medications are prescribed to treat adverse reactions or iatrogenic disease.

Certain social factors are identified as influencing older persons’ adherence to drug regimens. Older people are more likely than other age groups to be on a fixed income, and this can mean that affording prescribed medication might be difficult at times. Older people also have high usage of over-the-counter medications such as laxatives and analgesics, and this may increase the likelihood of adverse reactions and drug interactions30.

Mrs Anderson’s daughter contacted her brothers to discuss their father’s care while their mother was hospitalised. The siblings agreed that their father should spend one week at each of their homes, during which time they would investigate the possibility of nursing home respite care for their father. Mr Anderson was furious when his children informed him of the arrangements they had made and refused to leave his home. He shouted at them that he could manage very well, with the assistance of his daughter and the fortnightly home-care visitor, while his wife was in hospital.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree