The first step in caring for a patient and in soliciting active cooperation is to gather a careful and complete history.

In all patient concerns and problems, an accurate history is the foundation on which data collection and the process of assessment are based.

The comprehensiveness of the history elicited depends on the information available in the patient’s record and the reliability of the patient.

Time spent early in the nurse-patient relationship gathering detailed information about what the patient knows, thinks, and feels about the problems prevents time-consuming errors and misunderstandings later.

Skill in interviewing affects both the accuracy of information elicited and the quality of the relationship established with the patient. This point cannot be overemphasized; the reader is encouraged to consult other sources for detailed discussion of techniques of health interviewing.

The purpose of the interview is to encourage an exchange of information between the patient and the nurse and to establish rapport and understanding.

Provide privacy in as quiet a place as possible and see that the patient is comfortable.

Begin the interview with a courteous greeting and an introduction. Address the patient as Mr., Mrs., or Ms. and shake hands if appropriate. Explain who you are and the reason for your presence.

Make sure that facial expressions, body movements, and tone of voice are pleasant, unhurried, and nonjudgmental, and that they convey the attitude of a sensitive listener so the patient will feel free to express thoughts and feelings.

Avoid reassuring the patient prematurely (before you have adequate information about the problem). This only cuts off discussion; the patient may then be unwilling to bring up a problem causing concern.

At times, a patient gives cues or suggests information, but does not tell enough. It may be necessary to probe for more information to obtain a thorough history.

Guide the interview so the necessary information is obtained without cutting off discussion. Controlling a rambling patient is often difficult but, with practice, it can be done without jeopardizing the quality of the information gained.

Date and time.

Patient’s name, address, telephone number, race, ethnicity, religion, birth date, and age.

Name of referring practitioner.

Insurance data.

Name of informant—the patient may be the person giving the history; if not, record the name, address, telephone number, and relationship to the patient of the person giving the history. (The patient’s facility or clinical record may also be a valuable resource.)

Accuracy and reliability of informant—this is a judgment based on the consistency of responses to questions and on a comparison of information in the history with your own observations in the physical examination.

Explain the reasons why the information is needed to help put the patient at ease.

A brief statement of the patient’s primary problem or concern in the patient’s own words, including the duration of the complaint. Example: “hacking cough × 3 weeks.”

Purpose is to allow the patient to describe his or her own problems and expectations with little or no direction from the interviewer and to identify the overriding problem for which the patient is seeking help (there may be numerous complaints).

To obtain information, ask the patient a direct question, such as “For what reason have you come to the facility?” or “What seems to be bothering you most at this time?”

Avoid confusing questions, such as “What brings you here?” (“The bus.”) or “Why are you here?” (“That’s what I came to find out.”)

Ask how long the concern or problem has been present, for example, whether it has been hours, days, or weeks. If necessary, establish the time of onset precisely by offering such clues as “Did you feel this way a month (6 months or 2 years) ago?”

Write down what the patient says using quotation marks to identify patient’s words.

A detailed chronological picture, beginning with the time the patient was last well (or, in the case of a problem with an acute onset, the patient’s condition just before the onset of the problem) and ending with a description of the patient’s current condition.

If there is more than one important problem, each is described in a separate, chronologically organized paragraph in the written history of present illness.

Investigate the chief complaint by eliciting more information through the use of the pneumonic “OLD CARTS”:

Onset (setting, circumstances, rapidity, or manner in which it began).

Location (exact place where the symptom is felt, radiation pattern).

Duration (how long; if intermittent, the frequency and duration of each episode).

Character/course (nature or quality of the symptom, such as sharp pain, interference with activity, how it has changed or evolved over time; ask to describe a typical episode).

Aggravating/associated factors (medications, rest, activity, diet; associated nausea, fever, and other symptoms).

Relieving factors (lying down, having bowel movement).

Treatments tried (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic methods attempted and their outcomes).

Severity (the quantity of the symptom; eg, how severe on scale of 1 to 10).

Alternately, use the pneumonic PQRST: provocative/palliative factors, quality/quantity, region/radiation, severity, timing.

Obtain OLD CARTS data for all the major problems associated with the present illness, as applicable.

Clarify the chronology of the illness by asking questions and summarizing the history of present illness for the patient to comment on.

To determine the background health status of the patient, including present status, recent health conditions, and past health conditions, that will serve as a basis for nursing care planning for holistic patient care.

General health and lifestyle patterns—sleeping pattern; diet; stability of weight; usual exercise and activities; use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs.

Childhood illnesses, such as infectious diseases (if applicable).

Immunization—polio, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella, haemophilus influenza type b, hepatitis B, hepatitis A, pneumococcal, influenza, varicella, meningitis, human papilloma virus, herpes zoster, last purified protein derivative or other skin test, abnormal or unusual reactions (give date when possible).

Operation—indications, diagnosis, dates, facility, surgeon, complications.

Previous hospitalizations—physician, facility data (year), diagnosis, treatment.

Injuries—type, treatment, outcome.

Major acute and chronic illnesses (any serious or prolonged illnesses not requiring hospitalization)—dates, symptoms, course, treatment.

Medications—prescription drugs from all providers (including ophthalmologist and dentist); nonprescription drugs including vitamins, supplements, and herbal products; include dosage, length of use, and adherence.

Allergies—environmental allergies, food allergies, drug reactions; give type of reaction (hives, rhinitis, local reaction, angioedema, anaphylaxis).

Obstetric history (may appear in review of systems).

Pregnancies, miscarriages, abortions.

Describe course of pregnancy, labor, and delivery; date, place of delivery.

Psychiatric history (may appear in review of systems)—treatment by a mental health provider, diagnosis, date, place, medications.

Purpose is to present a picture of the patient’s family health, including that of grandparents, parents, brothers, sisters, aunts, and uncles because some diseases show a familial tendency or are hereditary.

Include age and health status (or age at and cause of death) of maternal and paternal grandparents, parents, siblings.

History, in immediate and close relatives, of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, gout, kidney disease or stones, thyroid disease, pulmonary disease, blood problems, cancer (types), epilepsy, mental illness, arthritis, alcoholism, obesity.

Genetic disorders, such as hemophilia or sickle cell disease.

Age and health status of spouse and children.

Purpose is to obtain detailed information about the current state of the patient and any past symptoms, or lack of symptoms, patient may have experienced related to a particular body system.

May give clues to diagnosis of multisystem disorders or progression of a disorder to other areas.

Include subjective information about what the patient feels or sees with regard to the major systems of the body.

General constitutional symptoms—fever, chills, night sweats, malaise, fatigability, recent weight loss or gain.

Skin—rash, itching, change in pigmentation or texture, sweating, hair growth and distribution, condition of nails, skin care habits, protection from sun.

Skeletal—stiffness of joints, pain, deformity, restriction of motion, swelling, redness, heat. (If there are problems, ask the patient to specify any activities of daily life that are difficult or impossible to perform.)

Head—headaches, dizziness, syncope, head injuries.

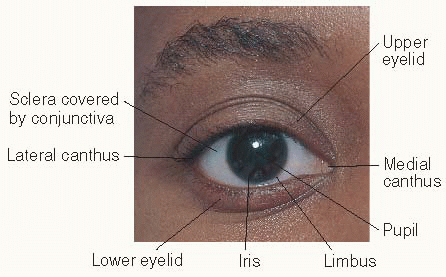

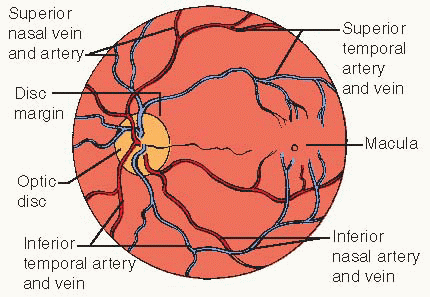

Eyes—vision, pain, diplopia, photophobia, blind spots, itching, burning, discharge, recent change in appearance or vision, glaucoma, cataracts, glasses or contact lenses worn, date of last refraction, infection.

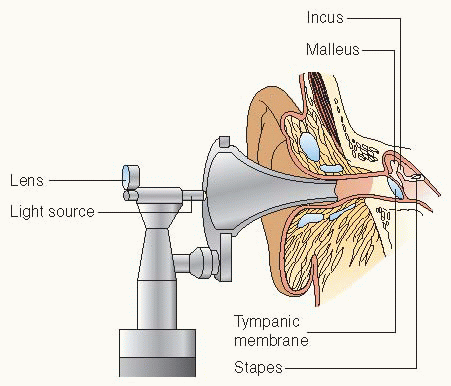

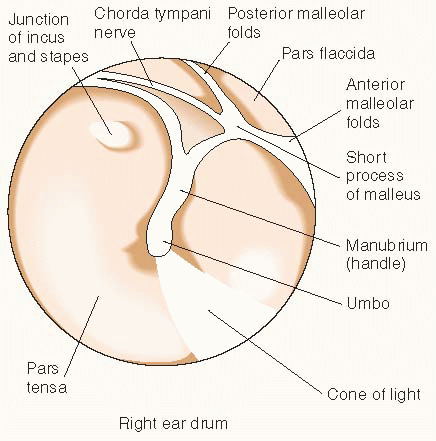

Ears—hearing acuity, earache, discharge, tinnitus, vertigo, history of tubes or infection.

Nose—sense of smell, frequency of colds, obstruction, epistaxis, postnasal discharge, sinus pain or therapy, use of nose drops or sprays (type and frequency).

Teeth—pain; bleeding, swollen or receding gums; recent abscesses, extractions; dentures; dental hygiene practices, last dental examination.

Mouth and tongue—soreness of tongue or buccal mucosa, ulcers, swelling.

Throat—sore throat, tonsillitis, hoarseness, dysphagia.

Neck—pain, stiffness, swelling, enlarged glands or lymph nodes.

Endocrine—goiter, thyroid tenderness, tremors, weakness, tolerance to heat and cold, changes in hat or glove size, changes in skin pigmentation, libido, easy bruising, muscle cramps, polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, hormone therapy, unexplained weight change.

Respiratory—pain in the chest with breathing, dyspnea, wheezing, cough, sputum (character, quantity), hemoptysis, last tuberculin test or chest x-ray and result (indicate where obtained), exposure to tuberculosis.

Cardiovascular—pain (aggravating and alleviating factors), palpitations, dyspnea, orthopnea (note number of pillows required for sleeping), history of heart murmur, edema, cyanosis, claudication, varicose veins, exercise tolerance, blood pressure (if known), last electrocardiogram and results (indicate where obtained).

Hematologic—anemia (if so, treatment received), tendency to bruise or bleed, thromboses, thrombophlebitis, any known abnormalities of blood cells.

Lymph nodes—enlargement, tenderness, suppuration, duration and progress of abnormality.

Gastrointestinal—appetite and digestion, intolerance to foods, belching, regurgitation, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, bowel habits, diarrhea, constipation, flatulence, stool characteristics, hemorrhoids, jaundice, use of laxatives or antacids, history of ulcer or other conditions, previous diagnostic tests such as colonoscopy.

Urinary—dysuria, pain, urgency, frequency, hematuria, nocturia, polydipsia, polyuria, oliguria, edema of the face, hesitancy, dribbling, loss in size or force of stream, passage of stones, stress incontinence.

Male reproductive—puberty onset, sexual activity, use of condoms, libido, sexual dysfunction, history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

Female reproductive—pattern and characteristics of menses, libido, sexual activity, satisfaction with sexual relations, pregnancies, methods of contraception, STD protection.

Breasts—pain, tenderness, discharge, lumps, mammograms, breast self-examination.

Neurologic—history of loss of consciousness, seizures, confusion, memory, cognitive function, incoordination, weakness, numbness, paresthesia, tremors, muscle cramps.

Psychiatric—how patient views self, mood changes, difficulty concentrating, sadness, nervousness, tension, irritability, change in social interaction, obsessive thoughts, compulsions, manic episodes, suicidal or homicidal thoughts, hallucinations.

To develop a plan of care that “fits” the patient. Here the interviewer finds out the many personal and family resources an individual has to aid in coping with the situation and determines what health promotion activities may be necessary.

Determine personal status—birthplace, education, armed service affiliation, position in the family, education level, satisfaction with life situations (home and job), personal concerns.

Identify habits and lifestyle patterns.

Sleeping pattern, number of hours of sleep, difficulty sleeping.

Exercise, activities, recreation, hobbies.

Nutrition and eating habits (diet recall for a typical day).

Alcohol—frequency, amount, type; CAGE questionnaire for problem drinking:

Have you ever thought you should Cut down on your drinking?

Have you ever been Annoyed by criticism of your drinking?

Have you ever felt Guilty about your drinking?

Do you drink in the morning (ie, an Eye-opener)?

Caffeine—type and amount per day.

Illicit drugs (illegal or improperly used prescription or over-the-counter medications).

Tobacco—past and present use, type (cigarettes, cigars, chewing, snuff), pack, years.

Sexual habits (can be part of genitourinary history)—

relationships, frequency, satisfaction, number of partners in past year and lifetime, STD and pregnancy prevention.

Home conditions.

Marital status, nature of family relationships.

Economic conditions—source of income; health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid.

Living arrangements and housing (owning or renting, heating, sewage, pets).

Involvement with agencies (name, caseworker).

History of physical or sexual abuse.

Occupation—past and present employment and working conditions, including exposure to stress and tension, noise, chemicals, pollution.

Cultural beliefs, religion or faith—its importance in coping and health practices.

A complete or partial physical examination is conducted following a careful comprehensive or problem-related history.

It is conducted in a quiet, well-lit room with consideration for patient privacy and comfort.

When possible, begin with the patient in a sitting position so both the front and back can be examined.

Completely expose the part to be examined but drape the rest of the body appropriately.

Conduct the examination systematically from head to foot so as not to miss observing any system or body part.

While examining each region, consider the underlying anatomic structures, their function, and possible abnormalities.

Because the body is bilaterally symmetric for the most part, compare findings on one side with those on the other.

Explain all procedures to the patient while the examination is being conducted to avoid alarming or worrying the patient and to encourage cooperation.

Begins with the first encounter with the patient and is the most important of all the techniques.

It is an organized scrutiny of the patient’s behavior and body.

With knowledge and experience, the examiner can become highly sensitive to visual clues.

The examiner begins each phase of the examination by inspecting the particular part with the eyes.

Involves touching the region or body part just observed and noting whether these are tender to touch and what the various structures feel like.

With experience comes the ability to distinguish variations of normal from abnormal.

It is performed in an organized manner from region to region.

By setting underlying tissues in motion, percussion helps in determining the density of the underlying tissue and whether it is air-filled, fluid-filled, or solid.

Audible sounds and palpable vibrations are produced, which can be distinguished by the examiner. The five basic notes produced by percussion can be distinguished by differences in the qualities of sound, pitch, duration, and intensity (see Table 5-1, page 50).

The technique for percussion may be described as follows:

Hyperextend the middle finger of your left hand, pressing the distal portion and joint firmly against the surface to be percussed.

Other fingers touching the surface will damp the sound.

Be consistent in the degree of firmness exerted by the hyperextended finger as you move it from area to area or the sound will vary.

Cock the right hand at the wrist, flex the middle finger upward, and place the forearm close to the surface to be percussed. The right hand and forearm should be as relaxed as possible.

With a quick, sharp, relaxed wrist motion, strike the extended left middle finger with the flexed right middle finger, using the tip of the finger, not the pad. Aim at the end of the extended left middle finger (just behind the nailbed) where the greatest pressure is exerted on the surface to be percussed.

Lift the right middle finger rapidly to avoid damping the vibrations.

The movement is at the wrist, not at the finger, elbow, or shoulder; the examiner should use the lightest touch capable of producing a clear sound.

Table 5-1 Five Basic Notes Produced by Percussion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This method uses the stethoscope to augment the sense of hearing.

The stethoscope must be constructed well and must fit the user. Earpieces should be comfortable, the length of the tubing should be 10 to 15 inches (25 to 38 cm), and the head should have a diaphragm and a bell.

The bell is used for low-pitched sounds such as certain heart murmurs.

The diaphragm screens out low-pitched sounds and is good for hearing high-frequency sounds such as breath sounds.

Extraneous sounds can be produced by clothing, hair, and movement of the head of the stethoscope.

Cotton applicator stick

Flashlight

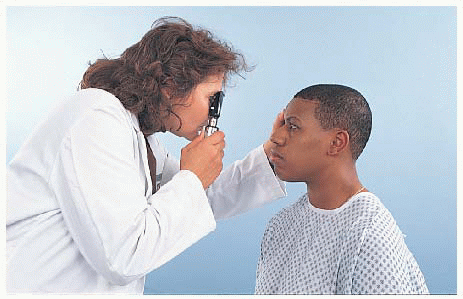

Oto-ophthalmoscope

Reflex hammer

Safety pin

Sphygmomanometer

Stethoscope

Thermometer

Tongue blade

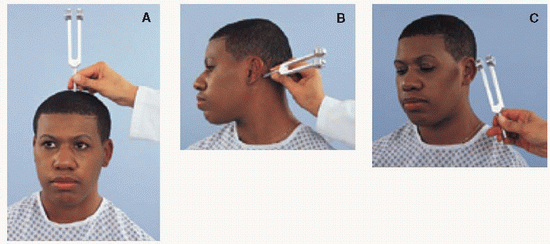

Tuning fork

Additional items may include disposable gloves and lubricant for rectal examination and a speculum for examination of female pelvis.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||