Activity and Exercise

Objectives

1. Describe normal activity and exercise patterns.

2. Describe how activity and exercise patterns change with aging.

3. Discuss the effects of disease processes on the ability to participate in exercise and activity.

4. Describe methods of assessing changes in the ability to participate in activity or exercise.

6. Identify selected nursing diagnoses related to activity and exercise problems.

8. Differentiate between a custodial focus and a rehabilitative focus in nursing care.

9. Discuss the impact of nurses’ attitudes on care planning.

10. Identify the benefits of a rehabilitative focus on older adults.

Key Terms

agility (ă- IL-

IL- -tē) (p. 303)

-tē) (p. 303)

alignment (ă- IN-mĕnt) (p. 307)

IN-mĕnt) (p. 307)

arthritis (ăhr-TH I-tĭs) (p. 305)

I-tĭs) (p. 305)

coordination (Kō-ŏr-dĭ-NĀ-shŭn) (p. 303)

custodial (kŭ-STŌ-dē-ăl) (p. 304)

dexterity (dĕk-STĔR-ĭ-tē) (p. 303)

diversional activities (dĭ-VŬR-zhăn-ăl) (p. 321)

dyspnea ( ISP-nē-ă) (p. 315)

ISP-nē-ă) (p. 315)

hemiparesis (hĕm-ē-pă-RĒ-sĭs) (p. 307)

hemiplegia (hĕm-ē-PLĒ-jă) (p. 307)

intermittent claudication (ĭn-tĕr- IT-ĕnt klaw-d

IT-ĕnt klaw-d -KĀ-shŭn) (p. 305)

-KĀ-shŭn) (p. 305)

isometric (ī-sō-MĔT-r k) (p. 307)

k) (p. 307)

isotonic (īi-sō-TŎN-ĭk) (p. 307)

rehabilitation (rē-hă-bĭl-ĭ-TĀ-shŭn) (p. 305)

rehabilitative (rē-hă-bĭl-ĭ-TĀ-tĭv) (p. 304)

tachycardia (tăk-ĕ-KĂR-dē-ă) (p. 314)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wold/geriatric

Normal activity patterns

The activity-exercise health pattern deals with behaviors related to exercise, activity, leisure, and recreation. Nurses must consider the wide range of behaviors within this pattern that fall under the general term activity. Activity is anything that requires the expenditure of energy. Some activities require only a small expenditure of energy, whereas others require a great deal of energy.

Basic body functions such as breathing, temperature control, and metabolism expend the least amount of energy. Sitting, resting, watching television, reading, and playing cards or bingo are sedentary activities that require little energy. Activities of daily living (ADL) such as dressing, grooming, eating, bathing, and toileting require a greater expenditure of energy. Cooking, cleaning, driving, and shopping require still more effort and expend more energy. Walking can be a mild or vigorous activity, depending on the pace. Running, swimming, dancing, aerobics, and other forms of active exercise require the greatest energy expenditure. Although the amount and type of exercise an individual performs change over the life span, exercise and activity remain an essential part of life. Persons who were not physically active as young adults are not likely to become physically active as they age. A healthy pattern of activity and exercise should be established early in life to ensure that these behaviors become habitual and are carried into old age.

Exercise helps people look and feel better. Physical activity is necessary to maintain normal joint mobility and muscle tone. When people do not participate in regular activity, all body systems suffer. Preventing mobility problems is easier than trying to overcome the problems when they develop. Older individuals should be encouraged to be as active and independent as possible. Because existing medical conditions may restrict activity, nurses should be aware of any problems that may affect the individual’s ability to participate in activities. Older adults should be assisted to do as much as is permitted.

Many aging individuals remain physically active. Today, it is common to see individuals in their sixties, seventies, and eighties leading active, self-sufficient lives. Aging no longer implies that a person must sit forever in a rocking chair or recliner and vegetate. All one has to do is visit a park or shopping mall early in the morning, where many older adults can be seen walking for their health. Access to golf courses is more difficult because of the amazing number of senior citizens playing 18 holes. Activity is good for people of all ages. Aging may change the type and amount of participation, but more and more people are realizing that active participation in a variety of activities is the best way to maintain high-level function.

Physical activity requires a complex interaction of physiologic processes, primarily those of the neurologic, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems. Anything that interferes with the coordination of these systems can alter the ability to participate in physical activity.

Of major importance is the function of the nervous system, which is the primary coordinating system of the body. The brain controls the involuntary activities of the body, including metabolism, respiration, and temperature control. Areas of the brain control the high-level processes of perception and cognition. Before any voluntary activity occurs, individuals must be able to recognize that a need for action exists. Once the need is recognized, the individual must have the desire, as well as the ability, to perform that action. The brain is also the motor control center of the body, and it communicates with the somatic peripheral nervous system. Any physiologic age- or disease-related change that alters the function of the brain’s motor centers or that interferes with the transmission of impulses from the brain to the musculoskeletal system can interfere with activity.

The musculoskeletal system must then be able to respond to these messages from the brain. Normal and pathologic changes in muscles or bones can interfere with normal activity. Even if the nervous and the musculoskeletal systems are intact, problems in the cardiovascular and respiratory systems can lead to alterations in activity. Muscles, including the heart muscle, require an adequate supply of oxygen and nutrients to function properly. Anything that interferes with the oxygen supply to tissues affects a person’s ability to perform activity.

Activity and aging

With advancing age, most people experience some changes in the ability to perform or tolerate activity, and this ability varies widely among older adults. In general, the more active a person has been, the more active he or she remains with aging.

The first change noticed by most aging persons is a decrease in the rate or speed of activity. Things that could be done quickly in the past now take longer. Many older individuals complain that it takes them much longer to dress, shop, or do other simple activities than it used to. Normal aging does not interfere with the transmission of nerve impulses, but it does slow the speed of nerve transmission.

A loss of muscle mass can interfere with activities that require muscular strength. Activities such as moving furniture, lifting bags of groceries, shoveling snow, and vacuuming may be increasingly difficult.

Loss of cushioning cartilage can result in arthritic joint pain, which inhibits motion and makes a person less likely to exercise. Ligaments and tendons become more stiff, contributing to decreased joint flexibility. This can result in problems with performing ADL. Reaching for objects on shelves, dressing, bending to put on shoes, and even washing the feet or back may be difficult.

Agility, the ability to move quickly and smoothly, decreases with age. This may cause difficulty when older adults try to climb ladders or avoid hazards while walking. Dexterity, the ability to perform fine manipulative skills, is also likely to decrease with age. Gross motor skills remain intact longer than do fine motor skills. However, skills that were perfected when younger, such as playing a musical instrument or sewing, may be maintained at a high level if the skills are used regularly.

Decreased stamina is typically seen with aging. This is most often a result of a decrease in oxygen supply to body tissues. Decreased oxygen exchange may be caused by a loss of elasticity in the lungs and a smaller chest cavity. The decreased availability of oxygen may lead to frequent pauses during activity or a slower pace when performing activities.

Coordination of multiple activities is likely to decrease with aging. Activities that require simultaneous perception of many stimuli and quick physical response (such as driving) are often affected. Older individuals with impaired vision and hearing, decreased strength, slow reaction time, and decreased coordination may not be able to safely perform this type of complex activity.

Because these changes appear gradually, most older individuals learn to compensate for or cope with them. Many strategies such as pacing activities, finding alternative methods of performing activities, and simplifying activities demonstrate the capacity of older adults to adapt and adjust.

Exercise Recommendations for Older Adults

Regular, planned exercise is of benefit to all ages, and it is of particular benefit as we age. Scientific evidence increasingly indicates that regular physical activity can extend years of active independent life, reduce disability, and improve the quality of life for older persons. Exercise helps gain or maintain muscle mass, strength, balance, coordination, and joint flexibility. It helps decrease stress and promotes normal sleep. Exercise does not have to be demanding to be of benefit. Current recommendations state that moderate exercise done for 30 minutes a day is more beneficial than strenuous exercise done infrequently. Because there may be medical reasons why certain activities are contraindicated, older persons should check with their physician before starting an exercise program. Physicians often refer older patients to a physical therapist, who can develop a plan specific to their needs. Elderly adults with special physical limitations will need an individualized plan developed to meet their unique needs. The proper exercise plan for a frail elderly person will be quite different from the plan most suited to a high-functioning 65-year-old. Physical therapists can recommend exercise programs designed for use by wheelchair-bound individuals or anyone with special needs. Before starting an exercise program, the older person should know the importance of acquiring good supportive footwear and clothing appropriate for the environment and type of exercise. Because elders are more at risk for thermal imbalance, they should be aware that it is wise to avoid excessive exercise during extreme weather conditions.

Specific types of exercise provide unique benefits. Aerobic or endurance exercises promote cardiovascular and respiratory function. Aerobic exercise includes activities that can be done at home, such as walking, biking, or square dancing. Many residential facilities, YMCAs, and senior centers provide additional opportunities for aerobic exercise using treadmills, rowing machines, steps, and others. Swimming is a pleasurable aerobic exercise for many seniors, and water exercises can help individuals with sore joints because the water provides support and eases movement. Even doing routine household chores and yard work can be considered aerobic if done for a long enough time. Resistance and conditioning exercise will help maintain muscle mass. These exercises can be done using exercise balls, inexpensive elastic stretch bands, or weights. More complex equipment may be available in health clubs or senior centers, but the individual must know how to use the equipment properly to avoid injury. Stretching exercises are important to promote joint flexibility. Little equipment is needed for these exercises, but caution should be used when doing standing exercises if the older person has balance problems. Balance training is particularly important for the elderly. Studies show that this training reduced falls by up to 17%. Even general exercise programs can reduce the incidence of falls by 10%.

Technologic innovations such as the Nintendo Wii and other interactive games appear to have the potential of stimulating interest in activity within the aging population.

Keeping motivated to exercise is a major problem at any age—perhaps more so as a person gets older. Nurses should educate older persons about the importance of exercise and emphasize the benefits such as weight loss, improved blood glucose control, lower blood pressure, decreased risk for falls, and others specific to the individual. Here are some guidelines that can help older adults make a regular exercise program a reality:

• Have a plan. Set up a weekly calendar with a planned time for exercise to keep on track.

• Keep it interesting. Join an exercise or dance class as a way to try some new form of exercise that is more interesting and motivating (see Complementary and Alternative Therapies box).

Focusing on the positive outcomes of exercise is key to maintaining a regular program. See the Nursing Process for Impaired Physical Mobility on pages 306–312 for additional benefits that can increase an older adult’s motivation to continue exercising.

Effects of disease processes on activity

If, in addition to normal changes, the aging person has health problems that affect the critical body systems, his or her ability to participate in activity is further impaired. Organic brain syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, and stroke can affect both the high-level thinking functions and the motor functions of the brain. Persons suffering from severe forms of these diseases may not recognize the need for the most basic activities such as moving, eating, dressing, bathing, or toileting. Even if they do recognize these needs, their altered motor function may prevent them from meeting basic needs.

Neurologic damage resulting from head injury, infection, degenerative disease, Parkinson’s disease, or toxic drug reactions can interfere with normal nerve impulse transmission. Older persons suffering from these conditions may recognize a need and have the desire to perform an activity yet are unable to carry out the activity. The nervous system does not transmit appropriate messages to the muscles to enable them to perform the activity. Abnormal nerve transmission can result in difficulty getting started with movement or in uncoordinated muscle activity (e.g., a staggering gait), which further limits the ability to participate in normal activities.

Diseases or injury to the musculoskeletal system can interfere with the ability to perform activity. Fractures can lead to limited or extensive mobility restriction, depending on the part or parts of the body affected. Fracture of a small bone such as a finger results in limited loss of mobility. Fracture of a large bone such as the femur results in severe limitation of mobility. Not only does the fracture itself restrict mobility, but also the treatment further limits mobility. Even after surgical repair, the person with a fractured hip is not permitted to participate in certain activities (e.g., weight bearing on the extremity) until healing has occurred. While waiting for healing to occur, strength and joint mobility can be lost if preventive nursing interventions are not instituted.

Diseases such as gout and arthritis cause joint pain, which leads to restricted activity. A person with severe gout or arthritis is likely to avoid use of the painful joints to reduce discomfort. Unfortunately, this inactivity can lead to further loss of joint mobility and muscle strength, which even further reduces the person’s ability to perform activities. Joint degeneration with aging severely restricts mobility, particularly in the weight-bearing joints in the knees and hips. Joint replacement surgery is an increasingly common option for older adults. After a period of rehabilitation, most older adults achieve a greatly improved activity level.

Foot conditions commonly seen in older adults (e.g., bunions, hammertoes, and calluses) may interfere with ambulation, particularly if footwear does not fit properly. Painful feet are a common reason for decreased activity in older adults.

Any disease condition that interferes with the intake or distribution of oxygen to body tissue significantly interferes with a person’s ability to participate in activity and exercise. These conditions include diseases of the respiratory system that prevent adequate gas exchange in the lungs (e.g., asthma, emphysema, bronchitis, and pneumonia) and diseases of the cardiovascular system that prevent adequate distribution of oxygen to body tissues and heart muscle (e.g., myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, heart block, arteriosclerosis, and hypertension).

Inadequate oxygenation places additional stress on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. Pulse and respiratory rates increase in an attempt to compensate for the decreased amount of oxygen. If additional demands for oxygen occur, as they do with even moderate activity, older adults may experience additional symptoms. Fatigue with minimal activity is common with oxygen deprivation. Pain may be reported with activity. Most common are angina (when the heart muscle does not receive adequate amounts of oxygen) and intermittent claudication (when the tissues of the lower extremities are deprived of oxygen). Initially, this pain occurs with activity only; in severe cases of deprivation, it also occurs at rest. Severe oxygen deprivation can result in cardiac or respiratory distress.

To compensate for these symptoms, older adults spontaneously restrict their activities. Individuals may become housebound because the effort of dressing is too much for them. Some are unable to eat or perform basic hygiene because it is too exhausting. Sometimes the activity limitation is so severe that individuals are able to maneuver around the house only by placing chairs at 10-foot intervals. They move that short distance, then sit and rest until they are able to move to the next chair.

Malnourishment can also contribute to the reduced ability to perform activity. Inadequate intake of nutrients can result in muscle atrophy. Malnourished individuals lack adequate protein to build muscle tissue, an adequate supply of glucose to fuel the muscles, and adequate iron to form hemoglobin. Inadequate iron intake can result in anemia, which leads to a decrease in the oxygen available to tissues and further reduces the ability to perform activity.

Although not physiologic in origin, emotional disorders such as severe grief, anxiety, or depression can lead to decreased participation in normal activity. Individuals who are emotionally disturbed may be directing all of their energy inward and may not be willing or able to summon the energy required for physical activity. It is important to remember that these people need to continue to use their bodies to prevent loss of physical function.

Nursing Process for Impaired Physical Mobility

Most older adults experience some changes in their ability to perform physical activities. These changes may result from the normal changes of aging or from some pathologic changes.

Assessment/Data Collection

• Does the individual have full range of motion in the joints?

• Does the person have any contractures or deformities?

• Does the person experience any pain or tenderness in the joints?

• Is there any particular motion that aggravates joint pain?

• How is the muscle tone of the arms and legs?

• Is muscle strength equal on both sides of the body?

• Is there any muscle tenderness?

• Is the person bedridden, wheelchair-bound, or ambulatory?

• If ambulatory, what is the pattern of the gait? Steady? Shuffling? Ataxic? Slow? Rapid?

• Is the person able to lift his or her feet when walking, or does the person shuffle?

• Does the person maintain an upright posture when walking?

• Do both sides of the body move evenly?

• How well can the person maintain balance?

• What kind of footwear does the person wear for walking?

• Does the person have any foot problems (e.g., bunions and calluses) that interfere with walking?

• How far can the person ambulate without discomfort?

• Does the person require any assistive devices (walkers or canes) for ambulation?

• Does the person know how to use these assistive devices properly?

• Does the person feel comfortable and confident using these aids?

• Does the person require the assistance of another person to ambulate?

• If the person is not ambulatory, what is his or her activity level?

• Does the person use a wheelchair?

• Can the person operate the wheelchair himself or herself?

• Does the person receive passive range-of-motion exercises?

Box 19-1 lists risk factors for impaired physical mobility in older adults.

Nursing Diagnosis

Impaired physical mobility

Nursing Goals/Outcomes Identification

The nursing goals for individuals with impaired physical mobility are to (1) increase participation in physical activities that maintain strength and mobility, (2) maintain normal anatomic position and function in all joints, (3) remain free from joint contractures and foot drop, and (4) maintain or increase strength and mobility using assistive devices.

Nursing Interventions/Implementation

The following nursing interventions should take place in hospitals or extended-care facilities:

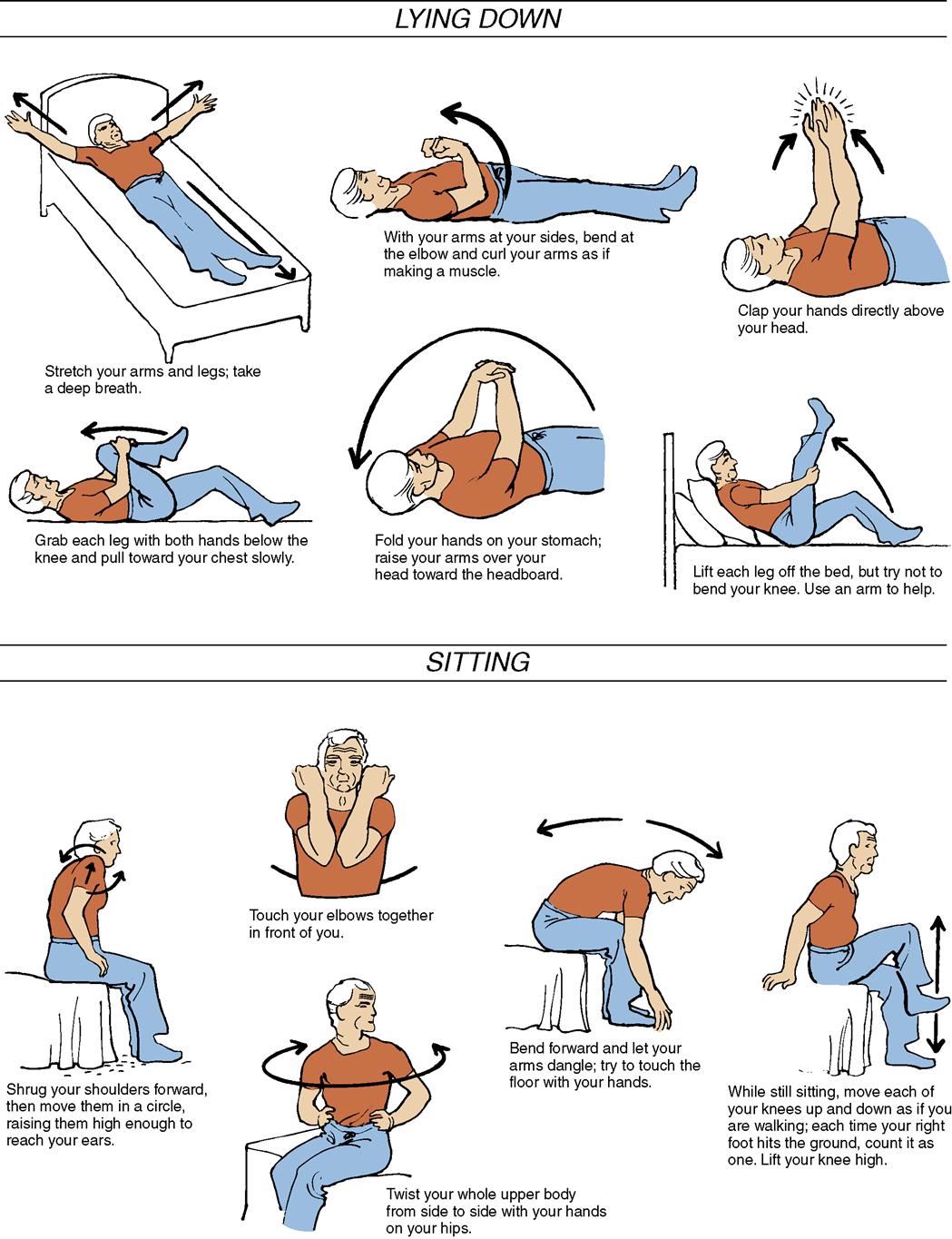

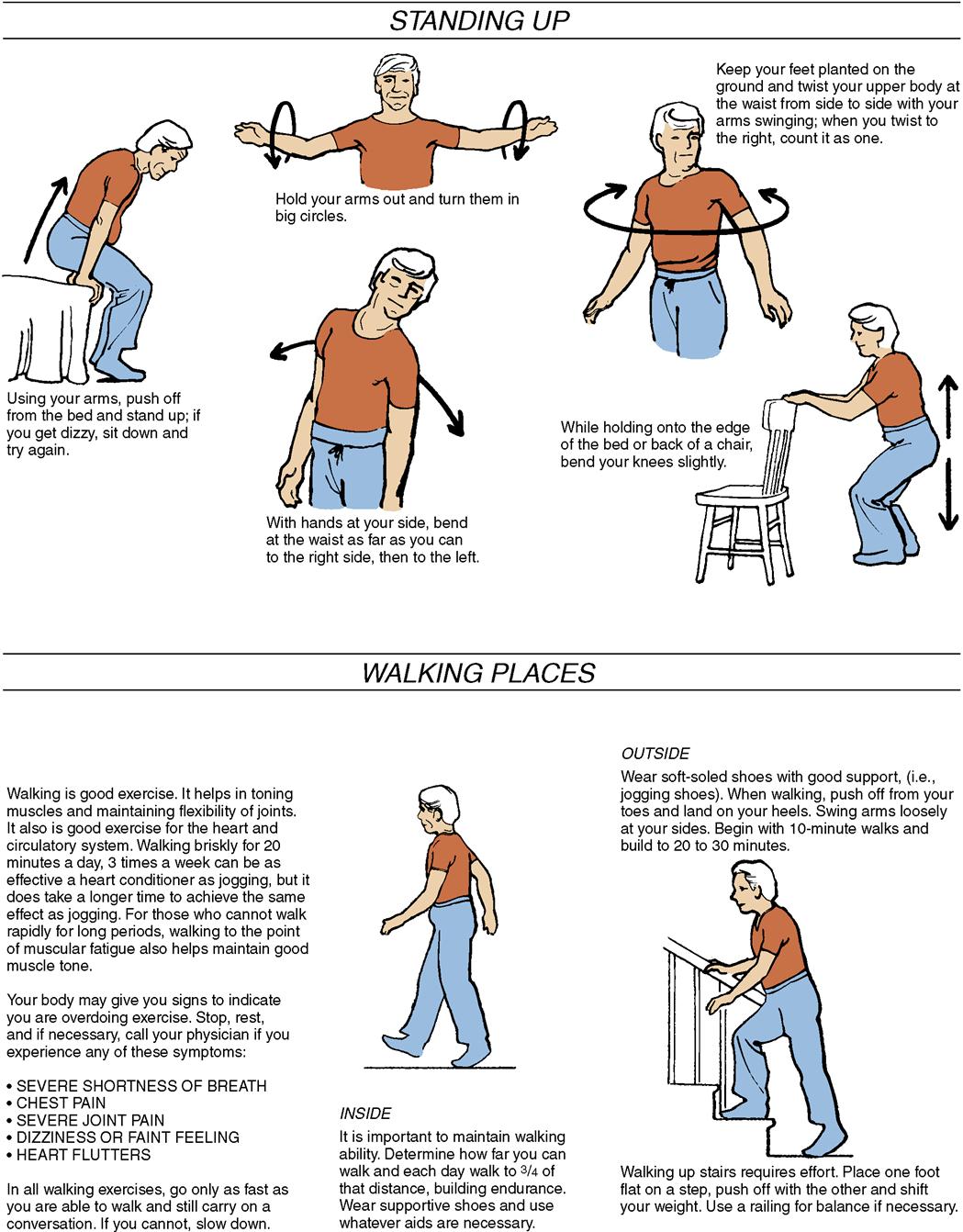

6. Consult with the physical therapist to determine a suitable activity/exercise plan that maintains muscle strength and joint mobility. The physical therapist may be able to suggest exercises that will benefit a specific individual. These exercises should become part of the nursing care plan and be included in the day’s activities (Figure 19-1). Passive range-of-motion exercises help keep the joints flexible, but they do little to maintain muscle strength. Passive range of motion should be provided a minimum of twice a day for immobile older individuals. Active range of motion helps with both joint flexibility and muscle toning. Older persons with hemiplegia or hemiparesis can be taught to use the stronger side of the body to exercise the weaker extremities. Many facilities provide exercise programs that are adapted to meet the ability levels of the residents. Exercise is often done to music because the rhythm encourages motion. Isometric exercises, such as alternately tightening and relaxing the muscles of the arms, abdomen, or buttocks, may benefit some older adults by helping them maintain the strength of the abdominal and gluteal muscles and quadriceps. Isometric exercise does not affect the joints. Isotonic exercise, which helps improve muscle strength, muscle tone, and joint mobility, includes such movements as lifting the body off of the bed with a trapeze (Figure 19-2), pressing against a footboard, or pushing against the bed to lift the buttocks off the mattress. Isometric and isotonic exercises should be used with caution by persons with cardiac problems because these exercises increase stress on the cardiovascular system. They may result in elevation of the blood pressure and use of the Valsalva maneuver, which can lead to cardiac overload or cardiac arrest. To prevent this problem, older adults should be instructed to breathe through the mouth while exercising.

9. Verify that the individual knows the correct method for using assistive devices and that he or she does, in fact, use them for activity. Explain proper use if needed. If assistive devices such as wheelchairs, walkers, or canes are needed, nurses should verify that older adults know how to use them properly (Figures 19-3 and 19-4). Nurses must verify that the older person knows how to use the walker, particularly when climbing stairs. The nurse should also verify that the person holds the cane in the correct hand when walking. To prevent falls, older adults should be reminded to lock the wheels of their wheelchair before sitting down. In addition, nurses should ensure that the assistive devices are kept nearby so that they are easily available to the older person. If the individual suffers from one-sided weakness, the device must be placed on the stronger side. Nurses must remember that many older adults do not like to use these devices because they are cumbersome and because they are constant reminders of failing health. Nurses must continue to stress the importance of using the devices if they are needed for safety.

11. Provide adequate assistance during ambulation. Gait belts and the assistance of one or two helpers may be needed to provide safety and a sense of security. The loss of balance seen in some older persons increases the risk for falls. A gait belt should be used when an unsteady person is being assisted. Gait belts that are properly secured around the person’s waist allow the caregiver to prevent injury to the individual. The belt is near the person’s center of gravity; thus the caregiver can sense subtle balance changes and anticipate problems (Figure 19-5). If the belt is too loose, it may slide up under the rib cage and cause injury. Regular belts on trousers or dresses may be used, but only with caution, because they are usually narrower and may not fasten as securely as a proper gait belt. Holding the arm of the older person to provide support is inadequate in most cases and should be avoided. If the older person starts to fall, the caregiver could dislocate the shoulder or cause other severe trauma to the older person.

The following interventions should take place in the home:

1. Teach or reinforce the benefits of regular activity and exercise. Many articles in senior citizen magazines and the popular press address the benefits of exercise (Box 19-2). Sedentary older adults may need to be reminded or encouraged to take this information to heart. Important information to communicate to older adults includes the fact that moderate or higher levels of physical activity are associated with lower mortality rates. Physical activity has been associated with many beneficial physiologic effects, including improved cardiovascular status, decreased risk for colon cancer, beneficial effects on noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, maintenance of normal muscle strength and joint function, reduced risk for falling, and decreased incidence of obesity. Activity also has psychologic benefits, including a decreased incidence of depression, improved mood, and an enhanced sense of well-being.

2. Assess the home for safety hazards or conditions that may interfere with mobility. The home may present conditions that interfere with mobility or increase the risk for falls. Modifications of the environment may be required to prevent accidents or injury. Chapter 9 addresses assessment of home safety in greater detail.

3. Help older adults develop a schedule for regular physical activity that is appropriate for their prescribed activity level. The physician should be consulted before an older person who has a chronic disease or has lived a sedentary lifestyle starts an exercise program. Once an appropriate target level is established, the individual should be taught to start slowly and build up to the optimal level over time.

Active older persons should be encouraged to participate in regular physical activity. Exercise should be planned into the day’s activities. If exercise is not viewed as important enough to plan for, it will not be done. Three 20- to 30-minute sessions a week on nonconsecutive days are good; daily exercise is even better. Midmorning is a good time for exercise, but afternoon and early evening are also good times. Much of the timing depends on the individual’s peak energy time. Blood supply may be diverted to digestion for up to 2 hours after large meals; therefore, intense physical activity should not be scheduled immediately after meals. Walking is one of the best exercises for older adults. Swimming and cycling are also recommended (Figure 19-6). Exercise programs, including aerobics classes, are sponsored by many senior citizen centers. Before joining this type of exercise program, older adults should see their physicians to ensure that the program is appropriate and safe for them. In addition to providing exercise, these programs provide an opportunity for social interaction. Exercising with others provides motivation and makes the effort more worthwhile and pleasant.

7. Use any appropriate interventions that are used in the institutional setting (Nursing Care Plan 19-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree