Chapter 12 Access to the bloodstream

Historical background

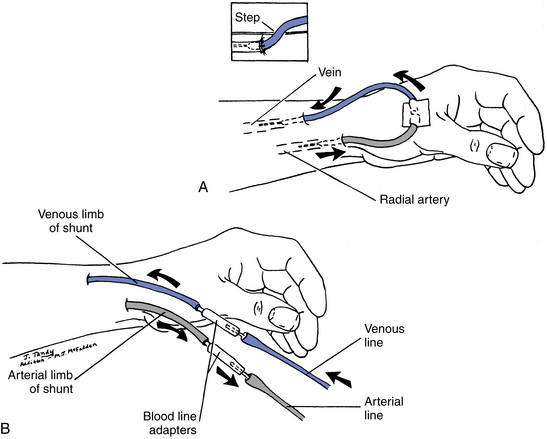

Vascular access, as used for hemodialysis in the early 1960s, has evolved considerably during the past 30 years or more. However, maintaining patent access with adequate blood flow remains one of the major problems in the chronically hemodialyzed patient (Fig. 12-1).

Internal accesses

The percentage of prevalent hemodialysis patients in the U. S. with an arteriovenous fistula (AV fistula) as their primary vascular access was 32.4% (87,344 patients) at the beginning of 2003. By May 2009 this percentage had increased to 52.6% (179,113 patients) (Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative Strategic Plan, 2009).

The Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative (FFBI) was established in 2005 by CMS to increase AV fistula use in all appropriate hemodialysis patients and to decrease the placement of central venous catheters. A group consisting of CMS and End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Networks has created a coalition that supports and promotes 13 “Change Concepts” that can give all hemodialysis patients the opportunity to receive an AV fistula. These Change Concepts are strategies to provide the patient and staff with the resources, tools, and best demonstrated practices to implement the KDOQI guidelines for vascular access placement.

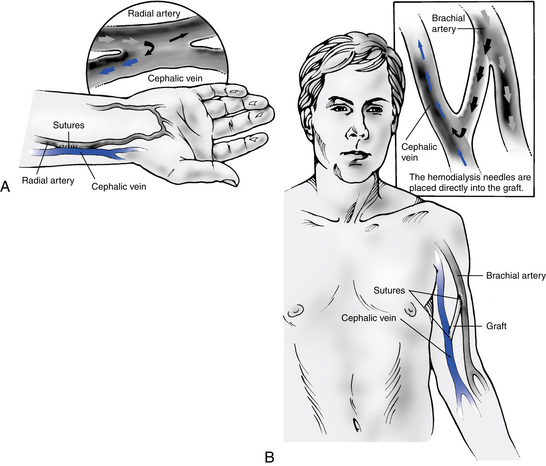

The order of preference for a vascular access for patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis is: (1) a wrist (radial-cephalic) primary arteriovenous fistula (Fig. 12-2, A), (2) an elbow (brachiocephalic) primary arteriovenous fistula, (3) an arteriovenous graft of synthetic material (Fig. 12-2, B), or (4) a transposed brachiobasilic vein fistula. If an AV fistula cannot be placed, an arteriovenous graft (AV graft) is acceptable. Long-term catheters, such as a cuffed tunneled central venous catheter, should be discouraged as a permanent vascular access. Short-term catheters may be used for acute dialysis but only for a limited duration of time (NKF KDOQI Vascular Access Clinical Practice Guidelines Update, 2006).

The time of vascular access placement should be well before the need for dialysis treatment. The 2006 NKF KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for chronic kidney disease (CKD) recommend initiation of a vascular access when the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. The goal is for the patient to have permanent and functioning access at the time when hemodialysis therapy is initiated. Early referral and placement provide the time needed for the fistula to properly mature and develop. Duplex ultrasound is the preferred method for preoperative vascular mapping and should be performed on all patients prior to placement of the vascular access (NKF Clinical Practice Guidelines and Recommendations, 2006).

Arteriovenous fistulas

What is an arteriovenous fistula?

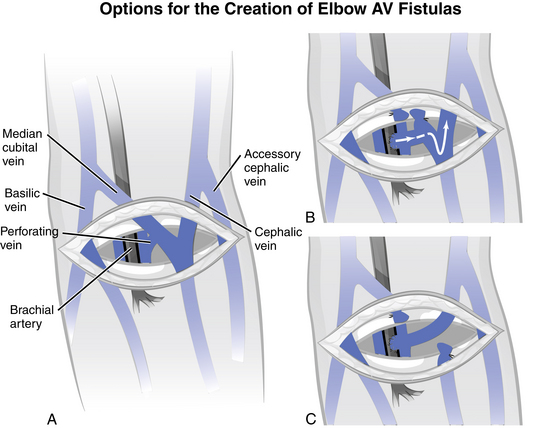

An AV fistula is an internal access surgically created by a vascular surgeon using the patient’s own blood vessels. In an internal AV fistula, a small (5 mm) opening is created surgically in an adjoining artery and vein, and the two vessels are joined at this opening, creating an AV fistula. The two blood vessels used are anastomosed in a side-to-side, end-to-side, or end-to-end connection (Fig. 12-3). The diversion of arterial blood into the vein causes the vein to become enlarged, distended, and prominent, allowing placement of large-gauge needles for the dialysis treatment. The blood flow rate (Qb) and diameter of the access will increase in response to the high pressure of the arterial blood entering the venous system. KDOQI has issued the rule of 6s as an objective measure used to assess access maturation. At six weeks after creation the fistula should have a diameter of at least 6 mm with discernable margins with a tourniquet in place and the depth should be no more than 0.6 mm below the skin surface. The FFBI defines a fully matured AV fistula as one that can sustain three consecutive two-needle cannulations with no infiltrations at the prescribed needle gauge and blood flow rate (NKF, 2006)(FFBI Coalition, Clinical Practice Workgroup, 2010).

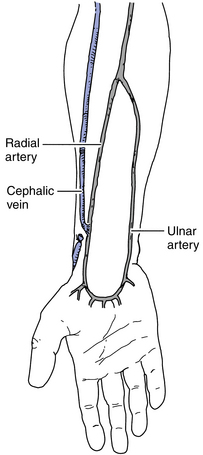

The AV fistula can be placed in either the upper or the lower arm. The radial artery and cephalic vein (lower arm) (Fig. 12-4) and brachial artery and cephalic vein (upper arm) are commonly used. Proper evaluation of the patient’s vasculature and physical assessment plays a role in determining the access of choice for that patient. A major cause of early AV fistula failure is the selection of suboptimal vessels. Venography allows for identification of appropriate veins and helps to rule out sites that are not suitable for use. Doppler flow studies may also be used if venography is not available.

Figure 12-4 Mid-forearm radiocephalic fistula is used if the distal radial artery is not suitable.

(From Wilson SE: Vascular access: principles and practice, ed 4, St. Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

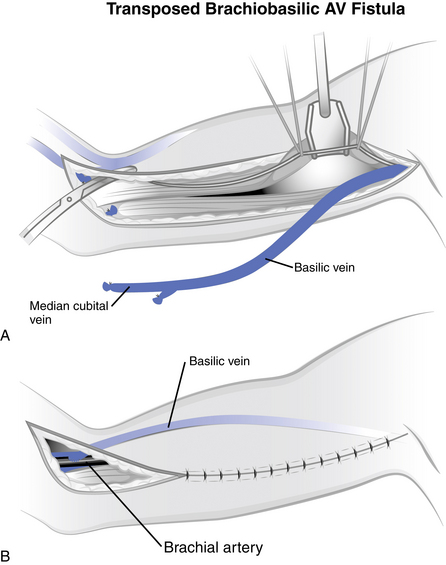

What is basilic vein transposition?

Basilic vein transposition is a technique used to create a vascular access in patients with inadequate vessels in the wrist. This transposed vessel technique involves dissecting the basilic vein and transposing it anteriorly and subcutaneously while anastomosing it to the brachial artery (Fig. 12-5). This transposed vessel provides a large surface area for cannulation and requires only one anastomosis. The incision for this access is rather large, with the start of the incision being at the midantecubital fossa and extending to the medial aspect of the arm to the axilla. The main advantage of this type of access placement is the avoidance of using a synthetic graft. As with other autologous grafts, you will see a longer patency rate and fewer risks of infection.

What is a proximal radial artery arteriovenous fistula?

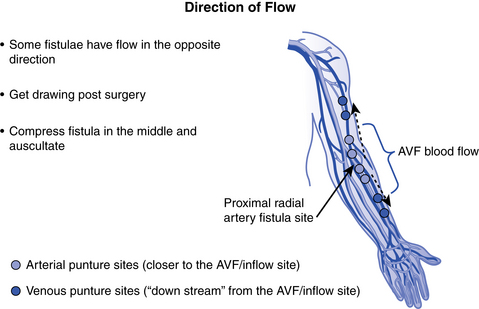

The proximal radial artery arteriovenous fistula (PRA-AVF), also known as a “reverse flow” fistula, is a newer advanced surgical procedure for native AV fistula placement. In this type of access, the proximal radial artery is used for the arterial inflow. The arterial anastomosis is made higher in the arm and the vein develops both above and below the anastomosis. With this configuration, blood will tend to flow in two directions at the same time, allowing cannulation in both the forearm and the upper arm. When cannulating, if both needles are to be placed in the forearm, the venous needle should be placed downstream (retrograde) with the needle top pointing toward the hand, which is the direction of blood flow. If the upper arm is used for the venous return, the flow goes toward the heart, so the needle would be placed upstream (antegrade) with the needle top pointing toward the shoulder (Jennings, Ball, & Duval, 2006) See Fig. 12-6.

What is an arteriovenous graft?

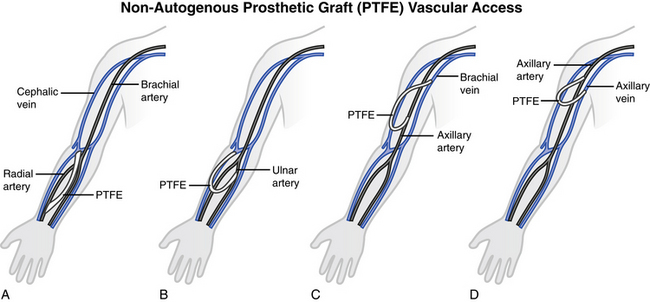

When a patient is not a candidate for a native AV fistula, a vascular graft is substituted. An AV graft can be of biologic or synthetic material; however, synthetic grafts are used most frequently. The graft material is implanted subcutaneously into either the forearm or the upper arm. In some circumstances when the arm cannot be used, the chest or leg area may be used. The graft bridges an artery on one end and a vein on the other end. Blood flow direction is from the artery to the vein. With the AV graft, the needles for cannulation are placed directly into the graft material.

The synthetic graft is used most often in patients who do not have adequate vessels to create an internal AV fistula. The graft may be placed in several configurations: straight, looped, or curved. NKF KDOQI guidelines recommend the use of PTFE over biologic or other synthetic materials. The AV graft may be used as early as two to six weeks after placement, with the surgeon’s approval. The tissue surrounding the graft will grow into and around the graft, helping to stabilize this vessel.

What types of arteriovenous grafts are available?

Synthetic grafts are the most common AV grafts currently in use. Many synthetic materials (Dacron, PTFE) are available in various diameters and lengths. A newer form of PTFE allows for needle insertion immediately after placement, although the manufacturer recommends waiting five to seven days. Fig. 12-7 shows two types of placement for synthetic grafts.

What are the advantages of an arteriovenous graft?

AV grafts can be used sooner than AV fistulas, usually after two weeks. Maturation time for the vessel to enlarge is not required. The larger vessel size allows for easier cannulation. Table 12-1 lists the advantages and disadvantages of internal accesses.

Table 12-1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Internal Accesses

| Arteriovenous fistula | Arteriovenous graft | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Excellent patency rate Can last for decades Highest blood flow rates Lowest rate of complications (infection, steal syndrome, stenosis) Improved performance over time as access develops Development of collateral circulation, which creates additional branches for cannulation | Large surface area for cannulation Ability to span large areas of the body Easy to cannulate Little time required for maturation Variety of shapes and configurations Ease of surgical implantation |

| Disadvantages | Failure of vein to enlarge More difficult to cannulate than graft Cosmetically unattractive Must find healthy veins that are in proximity and not too tortuous Requires time to mature before use | Higher rates of infection May reject graft material Higher rates of thrombosis Stenosis at venous anastomosis from intimal hyperplasia No development of collateral circulation |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree