CHAPTER 2 Abdominal pain

Inflammation of the peritoneum usually begins at the serosa covering the affected and inflamed organ, causing visceral peritonitis. The pain is a poorly localized aching. As the inflammatory process spreads to the adjacent parietal peritoneum, it produces localized parietal peritonitis. The pain of parietal peritonitis is more severe and is perceived in the area of the abdomen corresponding to the inflammation. The patient with parietal pain usually lies still and does not want to move.

Pain can be referred from within the abdomen or from other parts of the body (Box 2-1).

Box 2-1 Some Causes of Pain Perceived in Anatomical Regions

| Right Upper Quadrant | Periumbilical | Left Upper Quadrant |

| Duodenal ulcer | Ruptured spleen | |

| Hepatitis | Gastric ulcer | |

| Hepatomegaly | Aortic aneurysm | |

| Pneumonia | Perforated colon | |

| Cholecystitis | Pneumonia | |

| Right Lower Quadrant | Left Lower Quadrant | |

| Appendicitis | Sigmoid diverticulitis | |

| Salpingitis | Salpingitis | |

| Ovarian cyst | Ovarian cyst | |

| Ruptured ectopic pregnancy | Ruptured ectopic pregnancy | |

| Renal/ureteral stone | Renal/ureteral stone | |

| Strangulated hernia | Strangulated hernia | |

| Meckel diverticulitis | Perforated colon | |

| Regional ileitis | Regional ileitis | |

| Perforated cecum | Ulcerative colitis |

Modified from Judge R, Zuidema G, Fitzgerald F: Clinical diagnosis, ed 5, Boston, 1988, Little Brown.

Diagnostic reasoning: focused history

Is this an acute condition?

Key questions

How long ago did your pain start?

How long ago did your pain start?

Was the onset sudden or gradual?

Was the onset sudden or gradual?

How severe is the pain (on a scale of 1 to 10)?

How severe is the pain (on a scale of 1 to 10)?

If a child: What is the child’s level of activity?

If a child: What is the child’s level of activity?

Does the pain wake you up from sleep?

Does the pain wake you up from sleep?

What has been the course of the pain since it started? Is it getting worse or better?

What has been the course of the pain since it started? Is it getting worse or better?

When was your last bowel movement?

When was your last bowel movement?

Onset/duration

Perforation: look for signs and symptoms of peritonitis (Box 2-2)

Perforation: look for signs and symptoms of peritonitis (Box 2-2)

Ectopic pregnancy: in any woman of childbearing age

Ectopic pregnancy: in any woman of childbearing age

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: when back pain is present

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: when back pain is present

Box 2-2 Features of Peritonitis

Pain: front, back, sides, shoulders

Electrolytes fall; shock ensues

Rigidity or rebound of anterior abdominal wall

Tenderness with involuntary guarding

Increasing pulse rate, decreasing blood pressure

Temperature falls and then rises; tachypnea

Silent abdomen (no bowel sounds)

Modified from Shipman JJ: Mnemonics and tactics in surgery and medicine, ed 2, Chicago, 1984, Mosby.

Severity and progression

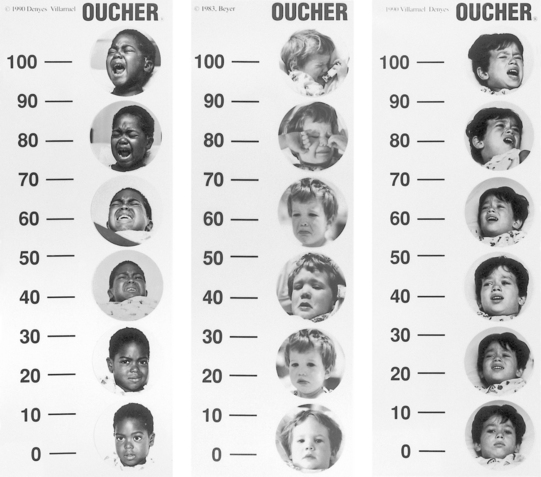

Severity is the most difficult symptom to evaluate because of its subjective quality. It is helpful to use a 1-to-10 scale in adults. Children often respond to the use of the pain faces or the Oucher Pain Scale (Figure 2-1).

Location of the pain

When blood, pus, or gastric fluid suddenly floods the peritoneal cavity, the pain is frequently reported as “all over the abdomen” at first. However, the maximum intensity of pain at the onset is likely to be in the upper abdomen with gastric problems and in the lower abdomen with tubal and appendix rupture. Irritating fluid from a perforated duodenal ulcer produces pain in the right hypochondrium, lumbar, and iliac regions.

Pain arising from the small intestine is always felt in the epigastric and umbilical areas of the abdomen. The ninth and eleventh thoracic nerves supply the small intestine via the common mesentery nerve. Appendicular nerves are derived from the same source as those that supply the small intestine, resulting in onset of pain in the epigastric area with appendicitis.

Table 2-1 describes the structures involved in specific pain locations.

Table 2-1 Pain Location and Involved Structures

| PAIN LOCATION | INVOLVED STRUCTURES |

|---|---|

| Epigastric | Esophagus, stomach, duodenum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen |

| Upper abdominal | Esophagus, stomach, duodenum, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, or thorax |

| Right upper quadrant | Usually esophagus, stomach, duodenum, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, or thorax; often indicates acute cholecystitis |

| Left upper quadrant | Spleen |

| Periumbilical | Jejunum, midgut, ileum, appendix, ascending colon; pain caused by inflammation, ischemic spasm, or abnormal distention |

| Lower abdominal | Colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and genitourinary structures—bladder, uterus, prostate |

| Right lower quadrant | Appendix, fallopian tube, ovary |

| Left lower quadrant | Sigmoid colon, fallopian tube, ovary |

| Flanks | Kidney(s) |

| Localized | Occurs from local inflammation of skin or peritoneum, as with appendicitis; lateralized pain occurs in paired organs—kidneys, ureters, fallopian tubes, gonads |

| Generalized | Produced by diffuse inflammation of gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, or abdomen wall |

Character of pain

Colicky or cramping pain occurs with obstruction of a hollow viscus that produces distention. Generally there are pain-free intervals when the pain is much less intense but still present, although it is subtle. During the painful episodes, the patient is exceedingly agitated and restless, and often pale and diaphoretic. The pain from obstruction of the small intestine is rhythmic, peristaltic pain with intermittent cramping. When the obstruction site is in the proximal small intestine rather than in the more distal portion, the paroxysms of cramping occur with greater frequency.

Vomiting

Severe irritation of the nerves of the peritoneum or mesentery. Sudden stimulation of many sympathetic nerves causes vomiting to occur early and to be persistent.

Severe irritation of the nerves of the peritoneum or mesentery. Sudden stimulation of many sympathetic nerves causes vomiting to occur early and to be persistent.

Obstruction of an involuntary muscular tube. Obstruction of any of the muscular tubes causes peristaltic contraction and consequent stretching of the muscle wall, which results in vomiting. The area behind the obstruction becomes dilated, and, as each peristaltic wave occurs, the tension and stretching of the muscular fibers are temporarily increased; therefore the pain of colic usually occurs in spasms. Vomiting usually occurs at the height of the pain.

Obstruction of an involuntary muscular tube. Obstruction of any of the muscular tubes causes peristaltic contraction and consequent stretching of the muscle wall, which results in vomiting. The area behind the obstruction becomes dilated, and, as each peristaltic wave occurs, the tension and stretching of the muscular fibers are temporarily increased; therefore the pain of colic usually occurs in spasms. Vomiting usually occurs at the height of the pain.

The action of absorbed toxins on the medullary centers. The chemoreceptor trigger zone is stimulated by drugs such as cardiac glycosides, ergot alkaloids, and morphine or by uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, or general anesthetics. Impulses to the medullary vomiting center then activate the vomiting process.

The action of absorbed toxins on the medullary centers. The chemoreceptor trigger zone is stimulated by drugs such as cardiac glycosides, ergot alkaloids, and morphine or by uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, or general anesthetics. Impulses to the medullary vomiting center then activate the vomiting process.

Stool characteristics

In children, mild diarrhea associated with the onset of pain suggests acute gastroenteritis but can also occur with early appendicitis. A low-lying appendix, close to the sigmoid colon and rectum, can induce an inflammatory process of the muscle wall of the sigmoid colon. Any distention of the sigmoid by fluid or gas signals the child to pass gas and small amounts of stool. The cycle repeats a few minutes later. In gastroenteritis, typically the child will have large liquid stools. Children can also have abdominal pain from chronic constipation. Constipation that precedes pain suggests disease of the colon or rectum.

Are there any clues to implicate a particular organ system?

Key questions

Cardiovascular system (Chapter 7):

Does the pain occur with exertion or at rest?

Does the pain occur with exertion or at rest?

Do you have any chest pain, palpitations, fast heartbeat, or pain that goes to the arm or jaw?

Do you have any chest pain, palpitations, fast heartbeat, or pain that goes to the arm or jaw?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree