Chapter 3 Distinguishing Between Specialization and Advanced Practice Nursing Distinguishing Between Advanced Nursing Practice and Advanced Practice Nursing Defining Advanced Practice Nursing Core Definition of Advanced Practice Nursing Seven Core Competencies of Advanced Practice Nursing Direct Clinical Practice: The Central Competency Additional Advanced Practice Nurse Core Competencies Differentiating Advanced Practice Roles: Operational Definitions of Advanced Practice Nursing Critical Elements in Managing Advanced Practice Nursing Environments Implications of the Definition of Advanced Practice Nursing This chapter considers two central questions that provide the foundation for this text: • Why is it important to define carefully and clearly what is meant by the term advanced practice nursing? • What distinguishes the practices of advanced practice nurses (APNs) from those of other nurses and other health care providers? Advanced practice nursing is considered here as a concept, not a role, a set of skills, or a substitution for physicians. Rather, it is a powerful idea, the origins of which date back more than a century. Such a conceptual definition provides a stable core understanding for all APN roles (see Chapter 2), it promotes consistency in practice that can aid others in understanding what this level of nursing entails, and it promotes the achievement of value-added patient outcomes and improvement in health care delivery processes. Advanced practice nursing is a relatively new concept in nursing’s evolution (see Chapter 1). Although debates and dissention are necessary and even healthy in forging consensus, ultimately the profession must agree on the key issues of definition, education, credentialing, and practice. This agreement is critically important to the survival, much less the growth, of advanced practice nursing. In this chapter, advanced practice nursing is defined and the scope of practice of APNs is discussed. Various APN roles are differentiated and key factors influencing advanced practice in health care environments are identified. The importance of a common and unified understanding of the distinguishing characteristics of advanced practice nursing is emphasized. The advanced practice of nursing builds on the foundation and core values of the nursing discipline. APN roles do not stand apart from nursing; they do not represent a separate profession, although references to “the nurse practitioner (NP) profession,” for example, are seen in the literature. It is the nursing core that contributes to the distinctiveness seen in APN practices. According to the American Nurses Association (ANA, 2010), contemporary nursing practice has seven essential features: These characteristics are equally essential for advanced practice nursing. Core values that guide nurses in practice include advocating for patients, respecting patient and family values and informed choices, viewing individuals holistically within their environments, communities, and cultural traditions, and maintaining a focus on disease prevention, health restoration, and health promotion (ANA, 2001; Creasia & Friberg, 2011; Hood, 2010). These core professional values also inform the central perspective of advanced practice nursing. Efforts to standardize the definition of advanced practice nursing have been ongoing since the 1990s (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 1995, 2006; ANA, 1995, 2003, 2010; Hamric, 1996, 2000, 2005, 2009; National Council of State Boards of Nursing [NCSBN], 1993, 2002, 2008). However, full clarity regarding advanced practice nursing has not yet been achieved, even as this level of nursing practice spreads around the globe. The growing international use of APNs with differing understandings in various countries has only complicated the picture (see Chapter 6). Different interpretations of advanced practice (AACN, 2006; ANA, 2005), debates about who is and is not an APN, and discrepancies in educational preparation for APNs remain issues for the international community, even as they are being standardized within countries. In spite of this lack of clarity (Ruel and Motyka, 2009; Pearson, 2011), emerging consensus on key features of the concept is increasingly evident. The definition that I have developed has been relatively stable throughout the five editions of this book. The primary criteria used in this definition are now standard elements used in the United States and, increasingly, elsewhere to regulate APNs. Similarly, consensus is growing in understanding advanced practice nursing in terms of core competencies. Even authors who deny a clear understanding of the concept propose competencies—variously called attributes, components, or domains—that are generally consistent with, although not always as complete as, the competencies proposed here. It is important to distinguish the conceptual definition of advanced practice nursing from regulatory requirements for any APN role (in the regulatory arena, the alternative term advanced practice registered nurse [APRN] is most commonly used; NCSBN, 2008). Of necessity, regulatory understandings focus on the more basic and measurable primary criteria of graduate educational preparation, advanced certification in a particular population focus, and practice in one of the four common APN roles: nurse practitioner (NP), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), and certified nurse-midwife (CNM). This approach is clearly seen in the APRN definition outlined in the Consensus Model (NCSBN, 2008) and has been very helpful and influential in standardizing state requirements for APRN licensure across the United States. Although necessary for regulation, however, this approach does not constitute an adequate understanding of advanced practice nursing. Limiting the profession’s understanding of advanced practice nursing to regulatory definitions can lead to a reductionist approach that results in a focus on a set of concrete skills and activities, such as diagnostic acumen or prescriptive authority. Understanding the advanced practice of the nursing discipline requires a definition that encompasses broad areas of skilled performance (the competency approach). As Chapter 2 notes, conceptual models and definitions are also useful for providing a robust framework for graduate APN curricula and for building an APN professional role identity. Before the definition of advanced practice nursing can be explored, it is important to distinguish between specialization in nursing and advanced practice nursing. Specialization involves the development of expanded knowledge and skills in a selected area within the discipline of nursing. All nurses with extensive experience in a particular area of practice (e.g., pediatric nursing, trauma nursing) are specialized in this sense. As the profession has advanced and responded to changes in health care, specialization and the need for specialty knowledge have increased. Thus, few nurses are generalists in the true sense of the word (Kitzman, 1989). Although family NPs traditionally represented themselves as generalists, they are specialists in the sense discussed here because they have specialized in one of the many facets of health care—namely, primary care. As Cockerham and Keeling note in Chapter 1, early specialization involved primarily on-the-job training or hospital-based training courses, and many nurses continue to develop specialty skills through practice experience and continuing education. Examples of currently evolving specialties include genetics nursing, forensic nursing, and clinical research nurse coordination. As specialties mature, they may develop graduate-level clinical preparation and incorporate the competencies of advanced practice nursing for their most advanced practitioners (Hanson & Hamric, 2003; also see Chapter 5); examples include critical care, oncology nursing, and palliative care nursing. Advanced practice nursing includes specialization but also involves expansion and educational advancement (ANA, 1995, 2003; Cronenwett, 1995). As compared with basic nursing practice, APN practice is further characterized by the following: (1) acquisition of new practice knowledge and skills, particularly theoretical and evidence-based knowledge, some of which overlap the traditional boundaries of medicine; (2) significant role autonomy; (3) responsibility for health promotion in addition to the diagnosis and management of patient problems, including prescribing pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions; (4) the greater complexity of clinical decision making and leadership in organizations and environments; and (5) specialization at the level of a particular APN role and population focus (ANA, 1996; 2003; NCSBN, 2008). It is necessary to distinguish between specialization as understood in this chapter and the term population focus. The framers of the Consensus Model for APRN regulation were interested in licensing and regulating advanced practice nursing in two broad categories. The first was regulation at the level of role—CNS, NP, CRNA, or CNM. The second category was termed population focus and, although not explicitly defined, six population foci were identified: family and individual across the life span, adult-gerontology, pediatrics, neonatal, women’s health and gender-related, and psychological and mental health. These foci are at different levels of specialization; for example, family and individual across the life span is broad, while neonatal is a subspecialty designation under the specialty of pediatrics. Therefore, this term is not synonymous with specialization and should not be understood in the same light. As the Consensus Model states (NCSBN, 2008): The terms advanced practice nursing and advanced nursing practice have distinct definitions and cannot be seen as interchangeable. In particular, recent definitions of advanced nursing practice do not clarify the clinically focused nature of advanced practice nursing. For example, ANA’s 2010 edition of Nursing’s Social Policy Statement defines the term advanced nursing practice as “characterized by the integration and application of a broad range of theoretical and evidence-based knowledge that occurs as part of graduate nursing education.” This broad definition has evolved from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing’s “Position Statement on the Practice Doctorate in Nursing” (AACN, 2004), which recommended doctoral-level educational preparation for individuals at the most advanced level of nursing practice. The Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) position statement (AACN, 2004) advanced a broad definition of advanced nursing practice as the following: A definition this broad goes beyond advanced practice nursing to include other advanced specialties not involved in providing direct clinical care to patients, such as administration, policy, informatics, and public health. One reason for such a broad definition was the desire to have the DNP degree be available to nurses practicing at the highest level in many varied specialties, not only those in APN roles. A decision was reached by the original Task Force (AACN, 2004) that the DNP degree was not to be a clinical doctorate, as was advocated in early discussions (Mundinger, Cook, Lenz, et al., 2000) but, rather, a practice doctorate in an expansive understanding of the term practice. The AACN’s The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice (2006) distinguishes between roles with an aggregate, systems, and organizational focus (advanced specialties) and roles with a direct clinical practice focus (APN roles of CNS, NP, CRNA, and CNM), while recognizing that these two groups share some essential competencies. It is important to understand that the DNP is a degree, much as is the Master’s of Science in Nursing (MSN), and not a role; DNP graduates can assume varied roles, depending on the specialty focus of their program. Some of these roles are not APN roles as advanced practice nursing is defined here. The end result of this work requires a distinction to be made between the terms advanced nursing practice and advanced practice nursing. Advanced practice nursing is a concept that applies to nurses who provide direct patient care to individual patients and families. As a consequence, APN roles involve expanded clinical skills and abilities and require a different level of regulation than non-APN roles. This text focuses on advanced practice nursing and the varied roles of APNs. Graduate programs that prepare students for APN roles will have different curricula from those preparing students for administration, informatics, or other specialties that do not have a direct practice component (AACN, 2006). As noted, the concept of advanced practice nursing continues to be defined in various ways in the nursing literature. The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature defines advanced practice broadly as anything beyond the staff nurse role: “The performance of additional acts by registered nurses who have gained added knowledge and skills through post-basic education and clinical experience…” (Advanced Nursing Practice, 2012). As noted with the DNP definition, a definition this broad incorporates many specialized nursing roles, not all of which should be considered as advanced practice nursing. Advanced practice nursing is often defined as a constellation of four roles: the NP, CNS, CNM, and CRNA (NCSBN, 2002, 2008; Stanley, 2011). For example, the ANA’s Scope and Standards of Practice, Third Edition (2010) does not provide a definition of advanced practice nursing but uses a regulatory definition of APRNs: In the past, some authors discussed advanced practice nursing only in terms of selected roles such as NP and CNS (Lindeke, Canedy, & Kay, 1997; Rasch & Frauman, 1996) or the NP role exclusively (Hickey, Ouimette, & Venegoni, 2000; Mundinger, 1994). Defining advanced practice nursing in terms of particular roles limits the concept and denies the reality that some nurses in these four APN roles are not using the core competencies of advanced practice nursing in their practice. These definitions are also limiting because they do not incorporate evolving APN roles. Thus, although such role-based definitions are useful for regulatory purposes, it is preferable to define and clarify advanced practice nursing as a concept without reference to particular roles. • Advanced practice nursing is a function of educational and practice preparation and a constellation of primary criteria and core competencies. • Direct clinical practice is the central competency of any APN role and informs all the other competencies. • All APNs share the same core criteria and competencies, although the actual clinical skill set varies, depending on the needs of the APN’s specialty patient population. Actual practices differ significantly based on the particular role adopted, specialty practiced, and organizational framework within which the role is performed. In spite of the need to keep job descriptions and job titles distinct in practice settings, it is critical that the public’s acceptance of advanced practice nursing be enhanced and confusion decreased. As Safriet (1993, 1998) noted, nursing’s future depends on reaching consensus on titles and consistent preparation for title holders. The nursing profession must be clear, concrete, and consistent about APN titles and their functions in discussions with nursing’s larger constituencies: consumers, other health care professionals, health care administrators, and health care policymakers. Advanced practice nursing is the patient-focused application of an expanded range of competencies to improve health outcomes for patients and populations in a specialized clinical area of the larger discipline of nursing.1 Advanced practice nursing is further defined by a conceptual model integrating three primary criteria and seven core competencies, one of them central to the others. This discussion and the chapters in Part II isolate each of these core competencies to clarify them. The reader should recognize that this is only a heuristic device for clarifying the conceptualization of advanced practice nursing used in this text. In reality, these elements are integrated into an APN’s practice; they are not separate and distinct features. The concentric circles in Figures 3-1 through 3-3 represent the seamless nature of this interweaving of elements. In addition, an APN’s skills function synergistically to produce a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. The essence of advanced practice nursing is found not only in the primary criteria and competencies demonstrated, but also in the synthesis of these elements into a unified composite practice that conforms to the conceptual definition just presented. Certain criteria (or qualifications) must be met before a nurse can be considered an APN. Although these baseline criteria are not sufficient in and of themselves, they are necessary core elements of advanced practice nursing. The three primary criteria for advanced practice nursing are shown in Figure 3-1 and include an earned graduate degree with a concentration in an advanced practice nursing role and population focus, national certification at an advanced level, and a practice focused on patients and their families. As noted, these criteria are most often the ones used by states to regulate APN practice because they are objective and easily measured (see Chapter 21). First, the APN must possess an earned graduate degree with a concentration in an APN role. This graduate degree may be a master’s or a DNP. Advanced practice students acquire specialized knowledge and skills through study and supervised practice at the graduate level. Curricular content includes theories and research findings relevant to the core of a particular advanced nursing role, population focus, and relevant specialty. For example, a CNS interested in palliative care will need coursework in CNS role competencies, the adult population focus, and the palliative care specialty. Because APNs assess, manage, and evaluate patients at the most independent level of clinical nursing practice, all APN curricula contain specific courses in advanced health and physical assessment, advanced pathophysiology, and advanced pharmacology (the so-called three Ps; AACN, 1995, 2006, 2011). Expansion of practice skills is acquired through faculty-supervised clinical experience, with master’s programs requiring a minimum of 500 clinical hours and DNP programs requiring 1000 hours. As noted earlier in the ANA definition, there is consensus that a master’s education in nursing is a baseline requirement for advanced practice nursing (nurse-midwifery was the latest APN specialty to agree to this requirement; see ACNM, 2009). Why is graduate educational preparation necessary for advanced practice nursing? Graduate education is a more efficient and standardized way to inculcate the complex competencies of APN-level practice than nursing’s traditional on the job or apprentice training programs (see Chapter 5). As the knowledge base within specialties has grown, so too has the need for formal education at the graduate level. In particular, the skills necessary for evidence-based practice (EBP) and the theory base required for advanced practice nursing mandate education at the graduate level. Some of the differences between basic and advanced practice in nursing are apparent in the following: the range and depth of APNs’ clinical knowledge; APNs’ ability to anticipate patient responses to health, illness, and nursing interventions; their ability to analyze clinical situations and explain why a phenomenon has occurred or why a particular intervention has been chosen; the reflective nature of their practice; their skill in assessing and addressing nonclinical variables that influence patient care; and their attention to the consequences of care and improving patient outcomes. Because of the interaction and integration of graduate education in nursing and extensive clinical experience, APNs are able to exercise a level of discrimination in clinical judgment that is unavailable to other experienced nurses (Spross & Baggerly, 1989). Professionally, requiring at least master’s-level preparation is important to create parity among APN roles so that all can move forward together in addressing policymaking and regulatory issues. This parity advances the profession’s standards and ensures more uniform credentialing mechanisms. Moving toward a doctoral-level educational expectation may also enhance nursing’s image and credibility with other disciplines. Decisions by other health care providers, such as pharmacists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists, to require doctoral preparation for entry into their professions have provided compelling support for nursing to establish the practice doctorate for APNs to achieve parity with these disciplines (AACN, 2006). Nursing has a particular need to achieve greater credibility with medicine. Organized medicine has historically been eager to point to nursing’s internal differences in APN education as evidence that APNs are inferior providers. The new clinical nurse leader (CNL) role represents a new and different understanding of the master’s credential. Historically, master’s education in nursing was, by definition, specialized education (see Chapter 1). However, the master’s-prepared CNL is described as a generalist, a staff nurse with expanded leadership skills at the point of care (AACN, 2003). AACN’s recent revision of The Essentials of Master’s Education in Nursing (2011) was developed for this generalist practice, whereas the DNP Essentials (2008) are aligned more with the understanding of advanced practice nursing described here. Even though CNLs have expanded leadership skills and graduate-level education, they are clearly not APNs. APN graduate education is highly specialized and involves preparation for an expanded scope of practice, neither of which characterizes CNL education. The existence of generalist and APN specialty master’s programs has the potential to confuse consumers, institutions, and nurses alike; it is incumbent on educational programs to differentiate clearly the curricula for generalist CNL versus specialist APN roles to avoid role confusion for these graduates. AACN’s proposed 2015 deadline for APNs to be prepared at the DNP level continues to be debated (Cronenwett, Dracup, Grey, et al., 2011) and undoubtedly will not be realized, even though DNP programs are increasing dramatically in number (from 20 programs in 2006 to 182 by 2011 [http://www.aacn.nche.edu/membership/members-only/presentations/2012/12doctoral/Potempa-Doc-Programs.pdf). As a result, master’s-level programs that prepare APNs are continuing.

A Definition of Advanced Practice Nursing

Distinguishing Between Specialization and Advanced Practice Nursing

Distinguishing Between Advanced Nursing Practice and Advanced Practice Nursing

Defining Advanced Practice Nursing

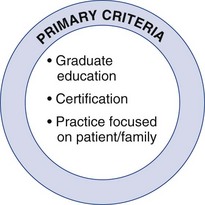

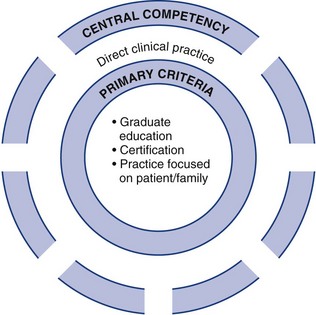

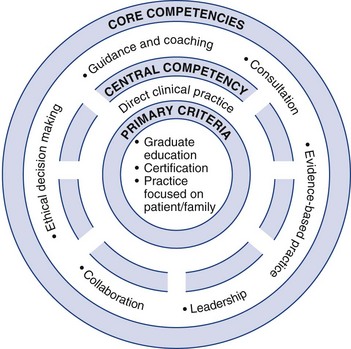

Core Definition of Advanced Practice Nursing

Conceptual Definition

Primary Criteria

Graduate Education

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

A Definition of Advanced Practice Nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access