Introduction

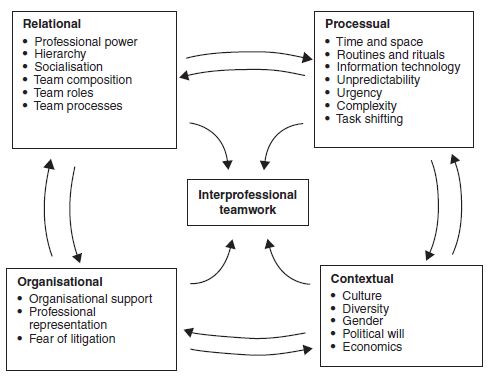

The chapter presents our conceptual framework for interprofessional teamwork as a way of navigating through the complex array of issues health and social care teams encounter in their everyday practice. We developed a framework comprising a number of factors which we have synthesised into four domains: relational, processual, organisational and contextual. These factors affect interprofessional teamwork in a number of different ways. In creating this framework we have attempted, where possible, to draw upon evidence-based sources. As we have previously noted, in the absence of evidence we have included work which we view as coherent, plausible and comprehensive. We describe and discuss each of these factors and their effect on interprofessional teamwork processes and outcomes. We also examine the interlinked nature of the factors, which for ease of presentation have been separated into four discrete main areas.

Through a wide range of sources gathered for our work of implementing and evaluating interprofessional education and practice, we identified a number of salient teamwork factors which we synthesised into the following four domains:

- Relational – factors which directly affect the relationships shared by professionals such as professional power and socialisation

- Processual – factors such as space and time which affect how the work of the team is carried out across different workplace situations

- Organisational – factors that affect the local organisational environment in which the interprofessional team operates

- Contextual – factors related to the broader social, political and economic landscape in which the team is located.

Figure 4.1 provides a diagrammatic representation of our framework. It outlines a number of separate factors in bullet form. As the arrows in Figure 4.1 suggest, each of these factors is linked with one domain, but has the ability to affect interprofessional teamwork in different ways. In the remainder of the chapter we discuss how these factors can affect (facilitate or inhibit) teamwork.

While, for simplicity, we have arranged these factors under four domains, there is some overlap between them, which we discuss later in the chapter. We should also note that although we have attempted to offer a framework which provides a comprehensive insight into a wide range of issues related to teamwork, this is not (nor could it be) an exhaustive set of factors. It is rooted within our shared interests on teamworking and so reflects our mutual interests. Therefore, in many ways this framework offers a sociologically informed view of interprofessional teamwork – a perspective which has been largely absent from the teamwork literature.

As indicated in Figure 4.1, we identified the following six relational factors: professional power, hierarchy, socialisation, team composition, team roles and team processes. Before we describe each, Box 4.1 provides an example of how a relational factor, in this case hierarchy, can affect interprofessional teamwork in a rehabilitation setting.

Box 4.1 Interprofessional teamwork and hierarchy.

Cott (1998) examined the meanings of ‘teamwork’ employed by an interprofessional team who worked in a hospital-based long-term older adult care unit. Drawing upon Strauss’ negotiated order perspective (see Chapter 5), she gathered interview data with team members. These data indicated the existence of two subgroups within the interprofessional team. One of the subgroups consisted of physicians, therapists and social workers who occupied a high position in the team hierarchy as they could take decisions on aspects of patient care. The other consisted of junior qualified and unqualified nursing staff who occupied lower positions in the hierarchy as they could not take such decisions. Cott also found that views of teamwork were largely dependent upon the type of work that was undertaken, as well as the position in the team hierarchy. It was reported that the subgroup of physicians, therapists and social workers collaborated in an equal fashion, discussing and agreeing on aspects of patient care. For this subgroup, teamwork was essentially viewed as vital for improving quality of care they delivered. By contrast, in the subgroup which consisted of junior qualified and unqualified staff, collaborative work was directed by a senior nurse. As a result, this subgroup did not decide how they worked together, nor did they have much direct contact with the physicians, therapists or social workers, who usually communicated with the senior nurse. In addition, this subgroup’s view of teamwork rested on the notion that it simply made their job easier to undertake.

Professional power

Power is a complex phenomenon. A number of sociological perspectives have described and analysed its multiple (positive and negative) dimensions (e.g. Clegg, 1989). In relation to power among the health and social care professions, as medicine was the first health care occupation to professionalise, it secured areas of high status knowledge and expertise and so attained high levels of social status and economic reward (Freidson, 1970). Over the years medicine has successfully protected these gains to achieve the dominant position of power in relation to the other health and social care professions. When one considers the nature of medicine’s power, it has the ability to influence the policymaking agenda, as well as (largely) control collaboration and care delivery processes (e.g. Fiorelli, 1988; Hugman, 1991; Gardezi et al., 2009). As a result of this dominance, it has been argued that medicine’s position is hegemonic in nature (Gramsci, 1988). But recent developments such as the rise of consumer movements and the increasing involvement of government in care (e.g. Ferlie et al., 1996) have weakened medicine’s traditional power base to some extent.

Mackay et al. (1995) have argued that engagement in interprofessional activities such as teamwork rests upon the readiness to share power. They go on to suggest that professions such as nursing and physiotherapy have a direct interest in collaborating with medicine, as it can help enhance their own influence over the care delivery process. Exploring this issue of equality within interprofessional teams, Gibbon (1999) points out that notions of power sharing between professions may mask the underlying power differentials:

In reality team members do not share equality […] this is part of the rhetoric of teamwork and is misleading at best, and patronising at worse. (p. 248)

When one considers the effects of power and the ability to influence decisions, behaviours and actions, according to Foucault (1978) one needs also to be aware of resistance to power. Resistance in interprofessional teams can come in different forms – passive (apathy towards other team members and collective work) and active, such as committing errors or the spoilage of shared projects (Gelmon et al., 2000; Delva et al., 2008). In our work we found resistance was usually played out in passive forms, such as non-attendance at team meetings (Reeves and Lewin, 2004).

Despite the inequalities of power which exist, and the friction that can be caused by such imbalances, interprofessional relationships need to be managed on a daily basis between practitioners in order to deliver patient care in a collaborative fashion. Chapter 6 outlines a number of interventions which may help engage team members in a range of activities designed to develop shared agreement around their daily collaborative work.

Hierarchy

Division of labour within many private and public sector organisations is hierarchical – a vertical arrangement whereby individuals with seniority have the authority to supervise the work of their juniors. The development and maintenance of hierarchies often rests upon social, economic and political inequalities. When one considers the nature of hierarchy between the health and social care professions, there are two main dimensions. First, as noted above, the professionalisation processes which occurred between the professions resulted in an emergence of an interprofessional hierarchy in which medicine occupies the dominant position. Second, each of the professions is internally organised along hierarchies based on experience and seniority – the more of each an individual has, the higher the position in the professional hierarchy they are usually located.

Hierarchical structures can have an inhibiting effect on interprofessional teamwork (e.g. Sexton et al., 2000; Di Palma, 2004). For example, they can disempower students and junior staff from making potentially valuable suggestions to their senior colleagues, as well as adversely affect engagement in interprofessional teamwork (see Box 4.1).

Relations between different interprofessional teams can also be impeded by hierarchy. Higher status teams, for example those in which members publish research, can achieve a high profile. As a result, their members are more likely to secure better access to organisational resources than colleagues who work in lower profile, lower status teams.

Hierarchies can be helpful. Such arrangements can ensure that more experienced staff are able to provide support to junior staff in their clinical practice. Nevertheless, attention is needed to ensure that hierarchical arrangements do not reinforce traditional notions of dominance or inhibit the free flow of communication between team members, as a recent study by Mahmood-Yousuf et al. (2008) on teamwork within a palliative care setting indicated.

Socialisation

Professional socialisation is a process in which individuals acquire the norms, values and attitudes associated with a particular professional group. As a result, certain patterns of language, dress, demeanour and behaviours are assumed and emphasised through ongoing interactions with peers and more senior members of the profession (Clark, 1997).

Sociological studies by authors such as Becker et al. (1961), and more recently Sinclair (1997), have indicated that professional socialisation usually results in individuals strongly associating and identifying with their professional group. Often, the socialisation leads to the adoption of a ‘closed’ professional identity with its own behaviours, language, values and attitudes, which can mean that engagement in interprofessional collaboration is regarded as a low priority. Indeed, Blane (1991) argued that socialisation results in individuals whose ‘primary loyalty is to their own profession’ (p. 231) and an inward looking stance which can impede efforts to engage in interprofessional teamwork.

Processes of professional socialisation often occur before an individual has entered their selected profession, often through the media. As Reeves and Pryce (1998) reported in their study of first year medical, nursing and dental students, many entered their respective professional course with pre-existing notions of traditional professional stereotypes and hierarchies. The effects of professional socialisation can therefore be profound. Indeed, as indicated above, they can lead to the development of values and attitudes which may profoundly undermine teamwork.

Team composition

Composition, in terms of size and membership, is a key element in how a team functions. There is some evidence which indicates that teams who have over ten members encounter more difficulties working together than smaller teams (e.g. Williams and Laungani, 1999). West (1994) has argued that a team which has over 25 members can be regarded as a small organisation, given the width of individuals’ needs, demands and interests. Naturally, the larger the team, the more difficult it will be to schedule meetings, coordinate members’ tasks and agree upon a joint approach. It has also been noted that within large teams, subgroups can emerge (Douglas, 2000). This can occur when a small number of members who hold ideas that diverge from the majority work together in an exclusionary fashion.

Handy (1999, p. 155) argues that large teams may have some advantages in terms of a greater amount of ‘talent, skills and knowledge’. He goes on to note, however, that there is usually more absenteeism and lower morale in larger teams; as members generally meet less and have limited opportunity for developing a team rapport.

The nature of team membership, in particular representation of different professional groups, can also affect function. For example, a community mental health team populated by many nurses and social workers can be overwhelming for the occupational therapist and psychologist who tend to operate as the only representative of their profession (Reeves et al., 2006).

Team roles

The formation and preservation of clear professional roles is seen as an essential element for effective interprofessional team relations and team performance (e.g. West and Markiowicz, 2004). Clear roles help define the nature of each team members’ tasks, responsibilities and scope of practice. Given the bounded nature of each profession’s scope of practice, there is a need to monitor and protect their areas of expertise. Clear roles within a team help ensure that problems around professional boundary infringement are avoided. Nevertheless, on occasions teams work in a generic manner where different team members share roles. For example, in remote rural areas, limited numbers of practitioners means that there is a need to regularly work across traditional professional boundaries. However, generic working can generate friction between team members as they are unclear about their respective professional roles (e.g. Booth and Hewison, 2002; Stark et al., 2002).

A key team role is that of the team leader (Martin and Rogers, 2004). A useful definition of an interprofessional team leader has been offered by Cook (2003), who regards them as individuals who influence others through their ability to motivate, take decisions and encourage innovation. A range of different leadership models can be found in the teamwork literature. In essence, they employ a continuum in which leaders can be placed somewhere between the extremes of autocratic or democratic approaches. Bass (1997), for example, argues there are two essential types of leaders, ‘transactional’ and ‘transformational’. The former adopt an authoritative approach, tend to work in isolation from the team and make decisions without including team members. By contrast, the latter adopts a democratic approach, works flexibly with members and promotes creative problem-solving within the team.

Leadership within interprofessional teams can be problematic. Separate professional responsibilities and different lines of management of members mean that identifying a single leader can be difficult (Øvretveit, 1993; Norman and Peck, 1999). Also, leadership is complicated as the team may need to change leaders when the care needs of their patients change. For example, in general medicine, a patient’s medical needs may be straightforward and met quickly, but their need for social care may become very complex. Team leadership, therefore, needs to shift from medicine to social work, as this change in patient care occurs. Although as we discussed above, medical dominance of the care process may mean this does not routinely happen.

Team processes

Team processes are multidimensional. We see them as including the following elements: communication, team stability, team emotions, trust and respect, teambuilding activities, conflict and humour.

Communication

Communication within interprofessional teams occurs in a variety of verbal and non-verbal forms. It can take place synchronously or asynchronously via the use of information technology (IT). Open and free-flowing communication between team members is important to their ability to deliver care in an effective fashion. Indeed, as we previously noted, miscommunication among professions has been the single most frequent cause of adverse clinical events. This can result in problems ranging from delays in treatment to medication errors to wrong site surgery. Effective communication can be difficult to achieve as these processes can be impeded by interprofessional tensions caused by hierarchy, socialisation and power differences. Communication can also be impeded when team members work in different locations at different times of the day or at night.

Team emotions

The emotional attachments individuals have with their teams can be influential. Writing from a psychodynamic perspective, Zagier Roberts (1994) argues that the membership of a team normally carries a distinct set of emotions. Often individuals can become very attached to the team they work within. Normally, this occurs because they have developed a deep commitment to their team as they find membership to be an emotionally rewarding experience.

Van Maanen and Kunda (1989) note that given the ebbs and flows of an individual’s emotions within a team, the notion of ‘emotional labour’ is useful to consider. Miller et al. (2008) explored how emotional labour affected interprofessional relations within an acute care setting. They found that nurses were strongly influenced by emotion in their interprofessional work. The establishment and maintenance of a nursing esprit de corps, friction with physicians and the failure of other team members to acknowledge their nursing work were all elements that affected their emotions and their readiness to engage in interprofessional work.

Trust and respect

The development of trust and respect within an interprofessional team is another important relational element. In many ways, trust and respect are built through shared experience, particularly during instances in which team members can demonstrate their technical skill and professional competence. Often a new member is not trusted until their abilities are proven (e.g. Rice Simpson et al., 2006; McCallin and Bamford, 2007). High levels of trust and respect, usually based on stable team membership (see below), can allow team members to work together in a close, integrated fashion (Ohlinger et al., 2003; Institute of Medicine, 2004b). An absence of these qualities can, however, be problematic. As Walby et al. (1994) found in their interviews with 127 doctors and 135 nurses, a lack of respect was reported as a key source of interprofessional conflict between these two professions across a range of clinical settings. In addition, poor levels of trust and respect contributed to poor knowledge of one another, limited commitment to shared team goals and fragmented interprofessional communication.

Humour

Te use of humour in teams can play a number of important functions. It can be employed to emphasise existing rules and boundaries, reinforce power imbalances or ease interprofessional tension. Griffiths (1998) explored the role and influence of humour within two community mental health teams. Both consisted of physicians, nurses, social workers and occupational therapists. Audio recordings of team meetings revealed that humour was used as a way of ‘letting off steam’ (p. 892) in relation to the general stresses and strains of working together. It was also a mechanism that helped team members support one another in their work with patients who had serious mental health problems. In addition, the study revealed that team members used humorous comments to ‘signal their unease about certain referrals’ (p. 884) to the team leader or to question a course of action with a patient. Often this resulted in a change to planned action by the team leader.

Conflict

As we discussed above, conflict between team members can arise due to a number of relational factors. While interprofessional conflict can be problematic to team relations and team performance, it can also have positive effects. West (1994), for example, states that conflict between members can be a source of innovation and ‘a source of excellence, quality and creativity’ (p. 71). Nevertheless, any conflict needs to be well handled within a team. If not, it can become damaging to interprofessional interactions and general team function.

It has also been found that an absence of conflict or friction within a team can develop a phenomenon termed ‘groupthink’ – where there is a lack of disagreement and debate between team or group members (Janis, 1982). In such teams, rather than seek opposing views and opinions, members prefer to focus upon reaching agreement and consensus. This can mean that teams fail to consider the range of possibilities around how they solve a particular problem. Recent work which explored the nature of decision-making in an interprofessional planning group indicated that a lack of critical analysis due to a shared need for consensus and agreement, contributed to the development of groupthink (Reeves, 2008).

Team stability

The stability of team membership can have an effect on interprofessional relations. The literature has suggested that a health care team with stable membership, is likely to perform in an effective manner as, over time, members will have been able to develop mutual understanding and trust with one another (e.g. West and Slater, 1996; Gair and Hartery, 2001). Nevertheless, as Vanclay (1996) noted in health and social care, achieving stability can be difficult. There may be a regular turnover of staff which can mean that there is rarely sufficient time for team members to ‘know each other well [and] foster a teamwork ethos’ (p. 1).

Individual willingness

Willingness to work in a collaborative manner cannot simply be assumed. An individual needs to be willing to engage in teamwork. As Henneman et al. (1995, p. 106) point out, ‘only the person involved ultimately determines whether or not collaboration occurs’. As we noted above, individuals can and do employ a range of subtle strategies to resist the influence of others to participate in activities they do not wish to undertake. Willingness to engage (or not) in teamwork can involve a number of factors. As Skjørshammer (2001) found, engagement in collaboration depended on a number of elements including the nature of the care task, its perceived urgency and need for interdependence between professions. Therefore, if an individual clinician felt that a care task had both low urgency and low interdependence, they may avoid engaging in interprofessional work.

Team-building

Regular team-building activities aimed at enhancing collaborative processes can help teams improve their performance. Typically, such activities include a range of interactive learning opportunities (e.g. workshops, retreats and, more recently, online sessions) which aim to develop and enhance teamwork attitudes, knowledge, skills and behaviours (also see Chapter 6). The use of team reflection activities can, for instance, be helpful for team function. West (1996) argues that teams who can spend time together reflecting upon their collaborative work can develop into a ‘reflexive’ team. The development of a reflexive team can help ensure that members are able to adapt and respond collectively to changes they encounter. While opportunities for team-building activities are regarded as important in improving shared performance, many teams can find it difficult to undertake these types of activities. Heavy workloads and limited resources mean that they often do not have the time or funding to undertake any team-building activities.

As indicated in Figure 4.1, we identified the following seven processual factors: time and space, routines and rituals, IT, unpredictability, urgency, complexity and task shifting. Before we describe each, Box 4.2 provides an example of how professions’ routines, as well as the spatial layout of a team’s base, can affect their ability to communicate and collaborate.

Box 4.2 How routines and spatial issues affect teamwork.

Drawing upon focus group data from six primary care teams, Delva et al. (2008) explored members’ views regarding what elements constituted a ‘team’ and what factors affected team effectiveness. A number of themes emerged relating to the roles and relationships of different members. Importantly, the study indicated that interprofessional communication was often impeded by two main factors. First, physician-based communication was problematic as their attendance at team meetings was poor because these meetings often conflicted with their profession-specific schedules. Second, nursing participants noted that the spatial layout of their clinic contributed to a lack of interaction between different members. As a result of these two factors, it was reported that information between team members was inconsistently shared and often incomplete in nature.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree