CHAPTER 8. Ending the consultation

• Introduction

• Patient not ready to change

• Patient still unsure

• Patient ready to change

• How do I know if I’ve done a good job?

• What if the change doesn’t last?

1 Where does this leave you now?

2 What would it be helpful for you to do between now and when we meet again?

3 What’s your next step?

4 Is there any information you’d like me to give you that would help you make your mind up about this?

5 What have you learned from previous attempts to change? What does your experience tell you about the best way to go about this?

Introduction

I haven’t really looked at it like that before. I need to go away and think about it some more before I make a decision about what to do.

I understand what you’re saying and I know you’re probably right but I just can’t see my way to doing it at the moment.

Consultations do not always have happy endings, with the patient going away with a clear action plan. When we are aware that our time for this meeting is running out, it can be tempting to try and push towards action to finish things up neatly. However, to do so is to run the risk of raising resistance, as the patient feels pressurized. Have you ever been considering buying a jacket and ended up leaving the shop without it because an over-pushy sales assistant tried to make the sale while you were still thinking about it? Or, have you ever considered a major purchase and then gone home to sleep on the decision before committing yourself? Hasty decisions are not always the best ones.

Our consultations are short. However, the journey towards change may be long. Early in the previous century, children would play a game bowling hoops along the road. The hoop had an impetus of its own. Its natural inclination was to roll along. Occasionally, it needed a nudge from the child to keep it on track or stop it falling over. Our consultations might be like the child’s nudge: helpful from time to time, but the real momentum for change is in the patient. Consequently, each consultation might be seen as one fragment of an overall process, rather than a discrete event. So what we need is a way of closing the session without closing the process. We may need to free ourselves from the assumption that a good consultation has to finish with a positive action plan. We do not have to ‘close the sale’ as they say in marketing.

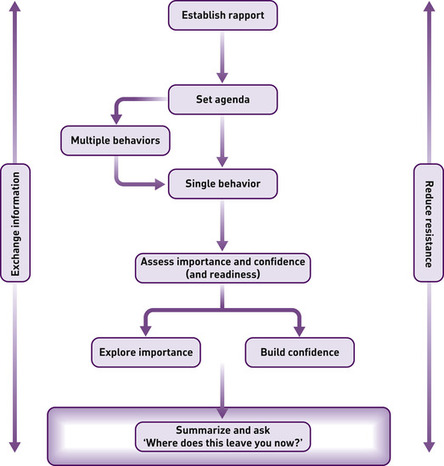

A good way to move towards closing the consultation is to summarize the discussion so far, and to ask an open question along the lines of, Where does this leave you now? The patient’s answer will tell you where to go next.

I can see it’s important but there are other things I think I need to prioritize at the moment. [Not ready to change]

I need to give this some more thought and talk it through with my family. [Still unsure]

I can see it makes sense for me to do it. What’s the best way to go about it? Where do we go from here? [Ready to change]

We want to be able to continue dialogue on this issue in future sessions. Three bad outcomes are as follows: first, if the patient goes away with a hastily constructed and unrealistic action plan, fails to keep to it and is embarrassed to come back and admit it. Second, it is unhelpful if the patient goes away feeling nagged and judged, and next time they need our help, they feel reluctant to come and see us (or even decide to change practitioner) because we keep trying to get them to change. Third, we will not do our best by them if we diagnose reluctant patients as being ‘in precontemplation’ and write them off, not bothering to raise the topic with them again.

Patient not ready to change

It is difficult to feel positive when someone has not made their mind up to change by the time the consultation ends. It is even more difficult, perhaps, when they have made a clear decision not to change! We know we have to respect their decision, but what does that really mean?

It does not mean we have to like it. On occasions, we may feel genuinely sad that they do not feel ready to do something that we think would be really helpful to them. We may feel exasperated because their continuing poor health or risk-taking will make more work for their families and for us. It means accepting that it really is their life and they absolutely have the right to make their own decisions about which risks to take and how to live. One person risks their health through obesity because they love fatty food; another risks injury by spending their holidays downhill skiing because the danger itself makes it exhilarating. Our role is to ensure, as far as we are able, that these decisions are informed and thoughtful.

In some circumstances, we have a harm-reduction role with patients who do not make healthy choices. We may treat smokers’ lung infections and discuss with them keeping their home smoke-free for the children, and we may medicate high blood pressure in patients who do not wish to make the lifestyle changes that would bring it down.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access