CHAPTER 8. Behavioral Analysis

Mark E. Safarik and Robert K. Ressler

Since the 1970s, investigative profilers at the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime have been assisting local, state, and federal agencies in narrowing the focus of an investigation’s hunt for the offender by conducting behavioral analyses of all types of violent crimes. Criminal investigative analysis, or criminal profiling as it is popularly known, is a tool that is commonly employed by law enforcement in the investigation of unusual, bizarre, and exceptionally violent crimes (O’Toole, 1999). The types of crimes that lend themselves to this type of analysis include various types of homicide (sexual, serial, and mass murder), serial sexual assault, kidnapping, and extortions. Criminal investigative analysis does not provide the specific identity of the offender. Rather, it focuses on individual level case data, attempts to identify patterns and trends in connected cases, examines the behavior exhibited within each crime scene, and facilitates the identification of the kind of person most likely to have committed a crime by focusing on the major behavioral and personality characteristics of the offender. The criminal investigative analysis process seeks to assist law enforcement’s efforts to narrow the focus of violent crime investigations by generating leads relative to the type of person who may have committed the crime.

Criminal Investigative Analysis from Crime Scene Analysis

Criminal profilers and the process of criminal investigative analysis have often been portrayed in sensational manner in the media through such feature films as Silence of the Lambs, Taking Lives, and Red Dragon and the popular current television series Criminal Minds and CSI. The ability to focus the direction of a criminal investigation, especially one that involves a cold homicide, by describing attributes of the offender is a skill of the expert investigative profiler. Violent crime scenes always tell a story—a story written by the offender, the victim, and the unique circumstances of their interaction. During the crime, the offender acts a certain way as a result of many factors including personality, motivation, criminal sophistication, the influence of drugs or alcohol, and attributes unique to that particular crime including the victim’s response. Correctly interpreting the complex dynamics inferred from crime scene behaviors, along with information obtained from the analysis of available forensic evidence, can reveal critical information about how and why the crime occurred (O’Toole, 2006). Special agent profilers in the Behavioral Analysis Unit at the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Academy have demonstrated expertise in crime and crime scene analysis of a wide array of violent crimes, particularly those involving serial and sexual homicide, mass murder, and serial sexual assault, as well as particularly compelling cases of single or multiple homicides not involving serial killers.

Although commonly associated with unusual homicides and aberrant sex crimes, the methodology used to analyze and interpret behavior has been applied in other types of crimes, such as hostage taking (Reiser, 1982). Law enforcement officers need to learn as much as possible about the hostage taker in order to protect the hostages. In such cases, police are aided by limited verbal contact with the offender and possibly by access to the offender’s family and friends. The police must be able to assess the hostage takers in terms of what courses of action they are likely to take and what their reactions to various stimuli might be.

The assessment of terrorists, their culture, religious motivation, and ideology have become a focus of research (Wilson, 2000), especially in light of the attacks on U.S. soil on September 11, 2001. The FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit added an additional assessment unit in 2002 to specifically address threat assessment and terrorism both nationally and abroad.

Profiling has also been used to identify anonymous letter writers (Casey-Owens, 1984) and persons who make written or spoken threats of violence. In cases of the latter, psycholinguistic techniques have been used to compose a threat dictionary, whereby every word in a message is assigned, by computer, to a specific category. Words used in the threat message are then compared with those used in ordinary speech or writings. The vocabulary usage in the message may yield signature words unique to the offender. In this way, police may be able not only to determine that several letters were written by the same individual, but also to learn about the offender’s background and psychological state (Smith & Shuy, 2002).

Bombers and arsonists also lend themselves to profiling. A detailed study was conducted by the FBI’s National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime (Sapp, Huff, Kelm, & Tunkel, 2001) to study causal factors, personality, demographic, and behavioral attributes of bombers. Common characteristics of arsonists have been derived from an analysis of the uniform crime reports. Rapist behavior with victims ranging from young children to the elderly has been carefully studied over the years. Utilizing a careful and detailed interview of the rape victim about the rapist’s behavior, law enforcement personnel examine the verbal, physical, and sexual behavior exhibited by the offender during the commission of the crime as well as both pre- and post-offense behavior to build a profile of the offender (Hazelwood & Burgess, 2008). The rationale is that behavior reflects personality, and by examining behavior the investigator may be able to determine what type of person is responsible for the offense. Knowledge of these various crime scene and behavioral attributes can aid the investigator in identifying offender typologies that describe the personality, behavioral, and demographic characteristics of potential suspects. This information can be used to narrow the pool of available suspects and allow for a more focused approach in developing strategies for interviewing these suspects. Studies of the behavioral and forensic dynamics of particular types of crimes have by design focused on particular subgroups of offenders such as those who sexually assault children (Campbell and DeNevi, 2004, Holmes and Holmes, 2002, Lanning, 2001 and Meyers, 2004) or the elderly (Burgess et al., 2007 and Safarik et al., 2002). The advances in the forensic evaluation of crime scenes using DNA, fingerprints, and trace evidence as well as research in psychopathy and the behavioral sciences have opened new avenues in cold case investigation.

Criminal investigative analysis does not provide the specific identity of the offender. Rather, it indicates the kind of person most likely to have committed a crime by focusing on analyzing and interpreting crime scene variables and dynamic crime scene interactions to reveal behavioral, personality, and demographic characteristics of the offender(s).

Criminal investigative analysis in serial sexual homicides

Criminal investigative analysis has been found to be of particular usefulness in investigating the crime of serial sexual homicide. These crimes create a great deal of fear because of their apparently random and motiveless nature, and they are also given significant publicity. Consequently, law enforcement personnel are under great public pressure to apprehend the perpetrator as quickly as possible. At the same time, these crimes may be the most difficult to solve precisely because of their apparent randomness and the observation that no known relationship existed between the victim and the offender before the crime. There has been a considerable upswing in these types of murders. In the 1990s, the rate of serial sexual homicide climbed to an almost epidemic proportion. Estimates of these types of criminals indicate that from 8 to 40 individuals are at large roaming the United States, according to U.S. Department of Justice officials. Some of the more notorious cases have had victims numbering from 48 in the case of Gary Ridgeway, the Green River Killer, to as many as 165 as claimed by Henry Lee Lucas in Texas and his co-conspirator traveling companion Ottis Elwood Toole in Florida. (Author’s personal communications with Henry Lee Lucas at Williamson County, Texas, jail and Ottis Elwood Toole, Jacksonville, Florida [c. 1983]).

Offender Motivation

Some of the earliest attempts to capture the types of motives seen in homicides are noted in Boudouris’ (1974) study and Lashley’s (1929) description of the Chicago Homicide data set. When researchers spoke of motive, they were described as strongly related to the offender-victim relationship. Victim-offender relationships were categorized generally as domestic, friends and acquaintances, business, criminal transactions, noncriminal, and unknown, along with several others. In Lashley’s analysis the two categories that dominated the relationship spectrum were gang and criminal related and altercations and fights. Domestic homicides were noted to be infrequent. The conventional designations of motive recognized today were simply not described as such in the early twentieth century research.

In the early 1980s, the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit attempted to develop a motivational model for the classification of homicide. Early work by Hazelwood and Douglas (1980) delineated two categories, the organized nonsocial and the disorganized asocial, to assist in describing offenders who engaged in lust murder. These categories were not meant to explain all sexual homicides or serial homicides but in the ensuing decades have been assimilated into the law enforcement lexicon, representative or not, as an assessment tool used to categorize all types of homicides, not just lust murders. This work led Ressler, Burgess, and Douglas (1988) to further refine the design for a classification system for serial sexual murder based on crime scene characteristics. This work culminated with the publication of the Crime Classification Manual (CCM), now in its second edition. FBI agents in the Investigative Support Unit (the predecessor to the current Behavioral Analysis Unit) and Behavioral Sciences Unit collaborated with numerous law enforcement entities in the development of this classification system using the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) as a model. Homicide classification was structured by motive, and as such, four major categories were identified: criminal enterprise homicide, personal cause homicide, sexual homicide, and group cause homicide. Each major category had a number of subcategories, further specifying motive based on crime scene and forensic findings, victim characteristics, and investigative considerations.

Schlesinger (2004) presents a motivational model for understanding sexual homicide based on an analysis of the motivational dynamics of the antisocial act of the homicide itself describing external (sociogenic) factors that stimulate homicide at one end and internal (psychogenic) factors at the other extreme. Other dimensional motivational models have surfaced that look at, among other attributes, instrumental versus expressive violence and impulsive versus ritualistic behavior. These models, although useful, are dimensional in understanding a single aspect of the crime. Interpreting human behavior, especially from a criminal perspective, is a complex and multifaceted endeavor. When criminal behavior is described as homicide and more specifically serial homicide, interpreting the offender’s motive based on crime scene behavior has been found to be difficult at best.

Homicides may be interpreted as sexual homicides when sexual activity is observed. The observed sexual activity however, may be the external expression in service of the nonsexual needs of the offender and thus may be misinterpreted (Myers, Husted, Safarik, & O’Toole, 2006). Conversely, many sexual homicides do not have an overtly sexual component to them. When considering homicides without a distinct sexual component, can the method used by the offender to kill the victim, attributes of the crime scene, or characteristics of the victim be used to establish a motive? These same descriptors are more often used when the appropriate classification for the type of homicide is being assigned.

The usefulness of the identification of motive may depend on whether the approach is from the perspective of academic research or an operational interest for case solution. Law enforcement’s interest would focus on the usefulness of assessing motive as related to narrowing down a potential pool of suspects or providing investigative direction. Law enforcement investigators are in general agreement on several aspects related to the offender’s motive in a serial murder investigation:

• Motive is very difficult to discern and too abstract a concept to definitively identify when examining a violent crime scene.

• Directing investigative effort to discern the motive may cause the investigation to become derailed.

• Analyzing offender behavior and forensic evidence at the crime scene is more useful for determining both what an offender did and why.

• Motive is elusive and may not be helpful even when it can be reasonably determined.

• Complicating attempts to discern the motive in a crime is the fact that there can be more than one motive and they can be reprioritized by the offender, rising and falling in importance as the crime proceeds.

• An offender’s motives can evolve both within a particular crime as well as over a series of crimes creating problems during the early stages of an investigation.

• As stated earlier, there can be multiple motives, some of which may be easier to observe in the crime scene behavior than others.

• When considering the level of violence noted in most serial homicides, it may be tempting to differentiate the offender’s motives based on the level of injury. However, the motives in serial homicides do not appear as separate and distinct from other violent as well as nonviolent crimes.

• The offender’s goal in the crime should not be construed to be synonymous with his motivation.

• External constraints not controlled by the offender can further obfuscate the offender’s intended motive.

Collectively, assessing crime scene behavior, the context within which it appears, the temporal and chronological components, and the forensic evaluation of evidence is the key to successfully inferring the motivation(s) of the offender. An offender’s affect is often interpreted as the motivation (e.g., anger motivated) when in fact the affect can appear as a subtext for any number of different motivations (Myers et al., 2006). This is a particularly important distinction to make when assessing sexual homicide cases because excessive injury is often misinterpreted as anger related and thus suggestive of a relationship. Although it is not completely accurate to say that these crimes are motiveless, all too often only the perpetrator understands the motive(s), and it is thus unknown to the investigating officers. Lunde (1976) demonstrated this issue in terms of the victims chosen by a particular offender. Although the serial murderer may not know the victims, their selection is rarely random. Rather, it is based on the murderer’s perception of certain characteristics of those victims that are of symbolic significance to the perpetrator. An analysis of the similarities and differences among victims of a particular serial murderer may provide important investigative information concerning the “motive” in an apparently motiveless crime. This, in turn, may yield information about the perpetrator. For example, the murder may be the result of a sadistic fantasy or displaced anger in the mind of the murderer and a particular victim may be targeted because of a symbolic aspect of the fantasy (Douglas et al., 1986 and Safarik et al., 2002).

In such cases, the investigating officer faces a completely different situation from a case in which a murder occurs as the result of jealousy, domestic violence, or during the commission of another felony (e.g., robbery). In those cases, a readily identifiable motive may provide vital clues about the identity of a perpetrator. In the case of the apparently motiveless crime, the investigative profilers must look to other methods, as well as to conventional investigative techniques, in their effort to identify the perpetrator. In this context, criminal investigative analysis has been productive, particularly in those crimes where the offender has engaged in repeated patterns of behavior at the crime scenes.

Assessment of Murderers

Traditionally, two very different disciplines have used the technique of assessing murderers. The first involves mental health professionals who seek to explain the personality and actions of a criminal through a psychiatric evaluation and diagnosis. This is accomplished through a process often consisting of an interview, testing, and onsite evaluation of the individual in question. The mental health professional usually is in a position to examine the offender and through this examination seeks to explain the offender’s behavior. The second discipline involves law enforcement agents who seek to determine the personality, behavioral, and demographic characteristics of the offender through the analysis and interpretation of the behavioral dynamics and forensic examination of evidence left at the crime scene. The behavioral analyst who does not have the offender but only the crime scene behavior works contrary to the mental health professional. Forensic pathologists and law enforcement professionals are utilizing forensic nurse examiners (FNEs) and sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs) who work with victims and perpetrators of sexual assault to provide rape-homicide examinations in many jurisdictions across the United States. Because FNEs also work with homicide detectives during an investigation and are often requested to accompany law enforcement officers to the scene, it is important for this group of professionals to be knowledgeable of the actions and behaviors of those offenders who engage in a sexual assault of their victims and any evidence that may be useful in assessing and interpreting their criminal behavior.

Psychological Profiling to Criminal Investigative Analysis

As the violent homicide crime rate remains at high levels and criminals become increasingly sophisticated with their crimes, so must the investigative tools of law enforcement be sharpened. One tool that has been providing assistance to law enforcement since the 1970s is criminal investigative analysis. The FBI, and specifically the Behavioral Sciences Unit (BSU) in an effort to assist local police in finding the perpetrator of a homicide, first used the procedure in 1971 when it was known as psychological profiling. Though the profiling was done on an informal basis in connection with classroom instruction, the analysis proved to be accurate and the offender was apprehended. In the following years, profiles were informally prepared on a number of cases with a reasonable degree of success, and as a result, requests for the procedure by local authorities increased steadily. Detectives with cases that were unusual, exceptionally violent, or evidenced a significant amount of psychopathology increasingly sought help from agents in the BSU.

In the early 1990s, the operational component of the BSU that was responsible for the “criminal profiling” and traveling on various murder or rape cases was taken out of the BSU and placed in the FBI’s Critical Incident Response Group and called the Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU). Subsequent to the incident at Waco, Texas, the FBI placed all operational components needed during a crisis under one umbrella division. The BSU is still part of the training division but does not engage in operational behavioral crime analysis.

As increasing numbers of cases were sent in for assessment, several of the BSU criminal profilers (Ressler, Hazelwood, & Douglas) began the initial efforts to understand the dynamics of serial murder and sexual homicide and the offenders who perpetrated them. Initially referred to as psychological profiling, it was defined as the process of identifying the gross psychological characteristics of an individual based on an analysis of the crimes he or she committed and providing a general description of the person using those traits. The process normally involved five steps: (1) a comprehensive study of the nature of the criminal act and the type of persons who have committed these offenses, (2) a thorough inspection of the specific crime scene involved in the case, (3) an in-depth examination of the background and activities of the victim(s) and any known suspects, (4) a formulation of the probable motivating factors of all parties involved, and (5) the development of a description of the perpetrator based on the overt characteristics associated with his or her probable psychological makeup.

It is not known who first used this particular process to identify criminals; however, the general technique was used in the 1870s by Dr. Hans Gross, an examining judge in the Upper Styria Region of Austria and, according to some, the first practical criminologist. More recently, Dr. James Brussel, a New York psychiatrist, who provided valuable information in such famous cases as the Mad Bomber and Boston Strangler, popularized a similar approach to criminal investigation. In 1957, the identity of George Metesky, the arsonist in New York City’s Mad Bomber case (which spanned 16 years), was aided by psychiatrist-criminologist James Brussel’s staccato-style profile: “Look for a heavy man, middle-aged, foreign born, Roman Catholic, single, lives with a brother or sister; when you find him, chances are he’ll be wearing a double-breasted suit, buttoned.” Indeed, the portrait was extraordinary in that the only variation was that Metesky lived with two single sisters. Brussel, in discussion about the psychiatrist acting as Sherlock Holmes, explained that a psychiatrist usually studies a person and makes some reasonable predictions about how that person may react to a specific situation and about what he or she may do in the future. Profiling, according to Brussel, reverses this process. By studying an individual’s deeds, one deduces what kind of person the individual might be (Brussel, 1968).

The idea of constructing a verbal picture of a murderer using psychological terms is not new. In 1960, Palmer published results of a three-year study of 51 murderers who were serving sentences in New England. Palmer’s “typical murderer” was 23 years old when he committed murder. Using a gun, this typical killer murdered a male stranger during an argument. He came from a low social class and achieved little in terms of education or occupation. He had a well-meaning but maladjusted mother, and he experienced physical abuse and psychological frustration during his childhood.

Similarly, Rizzo (1981) studied 31 accused murderers during the course of routine referrals for psychiatric examination at a court clinic. His profile of the average murderer listed the offender as a 26-year-old male who most likely knew his victim, with monetary gain the most probable motivation for the crime.

Psychological profiling, a term not currently in use, has given way to the terminology and process of criminal investigative analysis. Techniques used by law enforcement today seek to describe a murderer in terms that provide identifiable characteristics, which are then incorporated into an investigative framework. Investigative behavioral analysts, often referred to by the public and media as profilers, gather their information from the crime scene in order to analyze what it may reveal about the type of person who committed the crime. The criminal investigative analysis process, contrary to the belief by many law enforcement investigators and its portrayal in the media as a method of actually identifying a specific perpetrator, serves to focus a law enforcement investigation’s effort to narrow down the pool of potential offenders by identifying certain personality, behavioral, and demographic characteristics of the type of offender who could be responsible for a particular violent homicide or sexual assault. The term profiling has many negative connotations, most notably associated with racial and drug profiling. The type of analysis conducted in the behavioral assessment of serial murder and sexual homicide focuses on individual-level case data, attempts to identify patterns and trends in connected cases, examines the behavior exhibited within each crime scene, and facilitates the identification of the major personality and behavioral characteristics of the offender (Douglas, Burgess, Burgess, & Ressler, 2006). It is because of the case-specific nature of the assessment that it is problematic to engage in gross generalizations about a particular homicide without having intimate knowledge of the details of that crime.

Law enforcement has had a number of outstanding investigators; however, the skills, knowledge, and thought processes of these investigators have rarely been captured in the professional literature. These people were truly the experts of the law enforcement field, and their skills have been so admired that many fictional characters (Wilkie Collins, Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, Mike Hammer, and Charlie Chan) have been modeled on these experts. Although Lunde (1976) believes that the murders of fiction bear no resemblance to the murders of reality, a connection between fictional detective techniques and modern criminal profiling methods may indeed exist. For example, it is attention to detail that is the hallmark of famous fictional detectives; the smallest item at a crime scene does not escape their attention. This trait is seen in Sergeant Cuff, a character in Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, widely acknowledged as the first full-length detective study. At one end of the inquiry there was a murder, and at the other end there was a spot of ink on a tablecloth that nobody could account for. “In all my experience … I have never met with such a thing as a trifle yet.”

However, unlike detective fiction, real cases are not solved by one tiny clue but the analysis of all clue and crime patterns. In fact, one of the fundamental tenants of crime scene analysis is to evaluate variables that explain why this person became the victim of homicide. While conducting an analysis of the behavior that is manifested at violent crime scenes, it is important to avoid becoming too focused on any one aspect of the crime scene and ascribing singular importance to it. The effort is not focused on reconstructing the exact detailed sequence of events. Such an attempt is impractical because of the innumerable possible interactions that could occur between the victim and offender. It is the totality of the circumstances rather than a single crime scene variable that is important in assessing not only what happened but why and how it happened. The most accurate way of assessing the overall victim-offender interaction is to consider the occurrence of various behavioral attributes in conjunction with one another. It is not only important to analyze the crime with respect to what is seen behaviorally but to integrate that analysis with what is factually known through investigative interviews and forensic evaluation of the evidence. Ultimately, assessing the motivation for the murder and placing the variables of the murder into context is paramount to establishing a framework for understanding the dynamics of this crime.

Criminal profiling has been described as a collection of leads; as an educated attempt to provide specific information about a certain type of suspect (Geberth, 2006); and as a biographical sketch of behavior patterns, trends, and tendencies (Vorpagel, 1998). Geberth (2006) has also described the profiling process as particularly useful when the criminal has demonstrated some form of psychopathology. The task of an investigative profiler in developing a criminal profile is similar to the process used by forensic clinicians to make a diagnosis and treatment plan: data are collected and assessed, the situation is reconstructed, hypotheses are formulated, a behavioral assessment is developed and tested, and the results are reported. In many aspects, this method represents the nursing process applied by forensic nurses in their role as associates to forensic pathologists and law enforcement agencies in the investigation of trauma and death. The original behavioral analysts learned profiling through brainstorming, intuition, and educated guesswork. Their expertise was the result of years of accumulated wisdom, extensive experience in the field, and familiarity with a large number of cases. As the discipline came under greater scrutiny both from a research standpoint as well as by the courts, behavioral profilers drew on their vast experience in working literally thousands of these case on their own and in group consultations (the experiential component). These analysts regularly attend postgraduate training courses in forensic pathology, psychopathy, and forensic bloodstain analysis, among many others. As the discipline has grown, so has the base of empirically based research. Analysts of the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit have conducted research in such diverse areas as school shootings (O’Toole, 2006), sexual assault and homicide of the elderly (Safarik et al., 2002 and Safarik and Jarvis, 2005), and the behavioral characteristics of bombers (Sapp, et al., 2001).

An investigative profiler brings to the crime scene the ability to make hypothetical formulations based on his or her previous experience. A formulation is defined here as a concept that organizes, explains, or makes investigative sense out of information and that influences profile hypotheses. These formulations are based on clusters of information emerging from the crime scene information, victimology, and from the investigator’s experience in understanding criminal actions. A basic premise of criminal profiling is that the way a person thinks (e.g., his or her patterns of thinking) and his or her personality direct that individual’s personal behavior.

Forensic investigators should gather detailed information from the crime scene to assist criminal investigative analysts in determining the type of person who committed the crime. These investigators must be as mindful of the behavioral evidence as of the forensic evidence they collect.

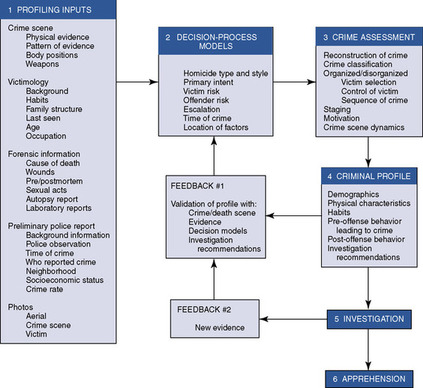

Generating a Criminal Profile

Investigative profilers at the FBI’s BAU, National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crimes (NCAVC), have been analyzing crime scenes and generating criminal profiles since the 1970s. Their description of the construction of profiles represents the offsite procedure as it is conducted at the NCAVC, as contrasted with onsite procedure (Douglas, et al., 1986). The criminal profile–generating process is described as five stages with the sixth, the outcome, being the apprehension of a suspect (Fig. 8-1).

|

| Fig. 8-1 |

The criminal profile-generating process has produced hundreds of profiles. A series of overlapping steps leads to the final goal of apprehension. These steps include:

1. Profiling inputs

2. Decision-process models

3. Crime assessment

4. Criminal profile

5. Investigation

6. Apprehension

There are two key feedback filters: (1) achieving congruence with the evidence, decision models, and investigation recommendations and (2) adding new evidence.

Profiling inputs

The profiling input stage begins the criminal profile–generating process. Information recorded by local law enforcement officers at the site or location of the crime is gathered and detailed. A thorough inspection of the specific crime scene yields information about physical evidence, patterns of evidence, body positions, number of scenes, weapons, their use and disposition, and other pertinent information.

The focus then moves to factors pertaining to the victim. An in-depth examination of the background and activities of the victim(s) provides information on the victim’s background, habits, family structure, and occupation, as well as when the victim was last seen. The cumulative information about the victim, referred to as victimology, is a crucial component to any crime analysis but more so for those homicides that appear motiveless. A decision is made about whether or not the victim was of low or high risk or if his or her risk level had been situationally changed. If low risk is the determination, questions about why the subject targeted the victim are formulated. More information on determining risk is discussed later in the chapter.

Forensic information is compiled about cause and type of death, antemortem and postmortem wounds, and sexual acts committed with the victim. Laboratory and autopsy reports provide a clear picture of the nature and severity of the injuries, which allows the investigator to determine the degree (or lack) of control the offender exhibited over the victim during the crime. For example, stabbings randomly made to the body (as contrasted with stabbings in one part of the body) and identifying defensive wounds may suggest the offender had difficulty controlling the victim. Preliminary police reports and investigative documents that include background information, police observations, time of crime, who reported the crime, socioeconomic status and crime rate of the neighborhood, and photos (aerial, crime scene, and victim [at scene and autopsy]) are sent for evaluation. The personal observations of the officers called to that scene as well as the circumstances under which they were called are all important. These reports do not include suspect information from local law enforcement.

The forensic nurse examiner should use written and photo-documentation to precisely preserve details about the dynamic interaction between the homicide offender, victim, and the scene including the victim’s injuries, movement within the scene, sexual acts, and postmortem activity, because such information is essential in order to conduct a behavioral assessment.

Decision-process models

The decision process begins the organizing and arranging of the inputs into meaningful patterns. Key decision points, or models, differentiate and organize the information from step 1 and form an underlying decisional structure for profiling.

Homicide: Type and Style

As noted in Table 8-1, type and style classify homicides. A single homicide is one victim, one homicidal event; a double homicide is two victims, one event and in one location; and a triple homicide has three victims in one location during one event. Anything beyond three victims is classified as a mass murder—that is, four or more victims killed during the same incident and usually in one location with no distinctive time element between the murders.

| *Recommendations from the 2005 International Serial Murder Symposium (Morton & Hilts, 2008) advocated that the spree murder classification be discontinued and subsumed into serial murder. | ||||||

| †Numbers in parentheses represent recommendations from the 2005 International Serial Murder Symposium (Morton & Hilts, 2008). | ||||||

| Style | Single | Double | Triple | Mass | Spree* | Serial† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of victims | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4+ | 2+ | 3+ (2+) |

| Number of events | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3+ (2+) |

| Number of locations | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2+ | 3+ (2+) |

| Cooling-off period (separate events) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

Classic Mass Murderer

There are two types of mass murderers: classic and family. A classic mass murderer involves one person operating in one location at one period of time. That period of time could be minutes or hours and might even be days. Classic mass murderers are usually described as mentally disordered individuals whose problems have increased to the point that they act against groups of people unrelated to these problems. The murderer unleashes this hostility through shootings or stabbings. One classic mass murderer was Charles Whitman, a man who armed himself with boxes of ammunition, weapons, ropes, a radio, and food; barricaded himself in a rooftop tower in Austin, Texas; and opened fire for 90 minutes, killing 16 people and wounding more than 30 others. He was stopped only when he was killed on the roof. James Huberty was another classic mass murderer. With a machine gun, he entered a fast-food restaurant and killed and wounded many people. Responding police also killed him at the site. Pennsylvania mass murderess Sylvia Seegrist (nicknamed Ms. Rambo for her military style clothing) was sentenced to life imprisonment for opening fire with a rifle aimed at shoppers in a mall in October 1985, killing three persons and wounding seven. On April 20, 1999, in a Littleton, Colorado, high school, anger had been building in students Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. On the 110th anniversary of Adolf Hitler’s birth, they swept through their high school corridors in a rampage before committing suicide, leaving 13 dead, 25 injured, and a community in shock. Some mass murderers remain at the scene of the killings and rather than surrendering, engage in behavior that forces the police to kill them in a phenomenon known as “suicide by cop.”

Family Member Mass Murderer

A second type of mass murderer is one who kills several family members (family annihilators). If more than three family members are killed and the perpetrator commits suicide, it is classified as a mass murder/suicide. On Christmas Eve 2008, Bruce Jeffrey Pardo, went to the home of his ex-wife’s relatives where his ex-wife and her family were having a Christmas Eve party. Pardo had come dressed in a Santa suit. Pardo methodically killed his ex-wife, her parents, and five other relatives before setting the house on fire. He then drove to his brother’s unoccupied home where he killed himself.

Without the suicide and with four or more victims, the murder is called a family killing. One example involves Vincent Brothers from Bakersfield, California, who shot and killed his wife, mother-in-law, and three young children in 2003. He also stabbed his wife postmortem. He staged the crime to make it appear that they had been killed during a botched break-in robbery. Brothers rented a car in Ohio and drove nonstop to Bakersfield, committed the homicides, and then drove back in order to give himself an alibi that he had been out of state at the time of the murders and therefore could not be responsible. Brothers had been the vice principal of an elementary school in Bakersfield. He was convicted and eventually sentenced to death.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access