CHAPTER 7. Triage

Nicki Gilboy

The number of patients seeking care in emergency departments (EDs) is increasing, while the number of EDs continues to decrease. 19 EDs are busier with about 50% reporting they are “at” or “over” capacity. 1 As a result, continuing ED crowding has placed even greater importance on the triage function and the role of the triage nurse.

Triage is the process of sorting patients as they present to the ED for care. The triage nurse must quickly identify those patients who need to be seen immediately and those patients who are safe to wait for care. This important decision needs to be based on a brief patient assessment that enables the triage nurse to assign an acuity rating. In many EDs the triage nurse will also decide in which area of the ED the patient will be seen. The overall goal of triage is to place the right patient in the right place at the right time for the right reason.

The word triage is derived from the French verb trier, which means to sort or to choose. Triage dates back to the French military, which used the word to designate a “clearing hospital” for wounded soldiers. The U.S. military used triage to describe a sorting station where injured soldiers were distributed from the battlefield to distant support hospitals. After World War II, triage came to mean the process used to identify those most likely to return to battle after medical intervention. This process allowed concentration of medical resources on soldiers who could fight again. During the Korean War, Vietnam War, and subsequent military conflicts, triage was refined to accomplish the “greatest good for the greatest number of wounded or injured men.”28

Most U.S. EDs use some sort of triage process to sort incoming patients. In the event of a catastrophic occurrence, when the number of incoming patients exceeds the capabilities of a department, a system of disaster triage is activated. Disaster triage begins at the scene, and patients are retriaged upon presentation to the ED. It is similar to military triage in that the goal is the greatest good for the greatest number of ill or injured. In a disaster the triage process is very rapid and includes a brief assessment of airway, breathing, perfusion, and mental status. Patients are assigned to one of four categories, and there is recognition that there are limited resources and some patients are not salvageable (see Chapter 17).

The concept of triage was first introduced into U.S. EDs in the 1950s when the volume of patients seeking emergency care increased. Many of these patients were presenting with nonurgent problems, and the process of seeing patients by time of arrival was no longer feasible. ED staff with a military background brought the concept of triage to the civilian EDs. At the same time physicians were moving away from solo practice and forming group practices with regular office hours. Patients seeking care during off-hours were referred to the local ED. The role of the ED as a provider of care at all times was established. 17

The number of U.S. ED visits in 2005 was 115.3 million. 19 Between 1995 and 2005 there was a 20% increase in ED visits, while the number of hospital EDs decreased 9% from 4,176 to 3,795. 19 Reasons cited for the increase in visits include the growing older adult population, an increase in the number of uninsured persons, and poor access to primary care or urgent care. 17 Because U.S. EDs are seeing an increase in number of patients seeking emergency care, a system for rapid, accurate triage upon presentation is critical to patient safety.

TRIAGE SYSTEMS

There is no single type of triage system used by all EDs in the United States. Three types of triage systems have been described in the literature. The simplest triage system is called traffic director. 17. and 26. In this type of system a nonclinical person is stationed at the ED entrance to greet patients upon presentation. Based on his or her initial impression, this nonclinical person decides if the patient should go to the waiting room or go to an open ED bed. Another system used by EDs with a lower volume of visits is called spot-check triage. For these departments it is not cost-effective to staff triage with a registered nurse (RN) 24 hours a day. Instead, the RN is notified when a patient presents. The RN does a quick look or brief assessment and then assigns a triage acuity. 17. and 26.

Comprehensive triage, the most advanced system, is performed by an RN and is the system recommended by the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA). 17 ENA’s Standards of Emergency Nursing Practice state: “The ED RN triages every patient and determines priority of care based on physical, developmental, and psychosocial needs as well as factors influencing flow through the emergency care system.”10 Based on this assessment, the RN will assign an acuity rating. There are many advantages to comprehensive triage, as follows:

• The triage process is conducted by an experienced ED RN whose competency has been validated.

• The RN is able to rapidly identify those patients in need of immediate care.

• Laboratory studies, x-ray examinations, and electrocardiograms can be initiated using triage protocols.

• The RN is able to provide reassurance to patients and families.

• First aid and comfort measures can be provided (in some EDs this may include medications for fever control and pain).

• Patient teaching can be initiated.

• Reassessment can be done.

• The RN can advocate for patients and work with the charge nurse to get patients to care.

• Patients in the waiting room are safe to wait. 13

The ENA recommends that the triage encounter take no more than 2 to 5 minutes. 31 Travers27 found that this was met only 22% of the time and the time frame was extended with patient age. The average time spent on comprehensive triage of the pediatric patient was 7 minutes. 18

Many EDs are using comprehensive triage, but some are struggling with how to manage the rapid influx of patients at various points in the day. Patients are waiting an unacceptably long period of time from entry into the ED (time of arrival) to actual triage time. Some EDs have addressed this issue by choosing to use a greeter as the first contact with ambulatory patients. Their role is to greet the patient, document time of arrival, and keep a list of the patients waiting for triage. Other EDs ask the patient or family member to write their name and reason for the visit on a list or card. The triage nurse uses this initial information from the greeter or from a list to determine the order in which patients are triaged. However, this system is not perfect and delays in care can occur. Delay may be due to the patient giving a vague description of why he or she came to the ED or the patient putting an incorrect label on his or her problem. For example, a patient tells the greeter, “I have a migraine,” when he or she is in fact having a stroke. To prevent this potential problem, some hospitals have adopted a two-tiered triage process or system.

Two-Tiered Triage Systems

In a two-tiered triage system the patient enters the ED and is greeted by an experienced ED RN who determines the chief complaint and conducts a rapid visual assessment to determine if this patient needs to be seen immediately or is safe to proceed to step two of the triage process. The first nurse initiates documentation. Those patients identified as needing to be seen immediately are taken to an open bed and registered at the bedside. Those patients identified as safe to wait are seen by the second triage nurse, who completes and documents a comprehensive triage assessment. The patient is then registered, and care may be initiated using triage protocols.

The advantage of a two-tier triage system is that an experienced ED nurse immediately screens all patients when they enter the ED. The patient with symptoms of a possible stroke, myocardial infarction, or other serious problem will be immediately identified and taken directly to a bed. EDs are faced with many quality measures with time parameters, such as a door-to-balloon time of 90 minutes, that the two-tiered system can help meet. 21 In a two-tiered system these patients are immediately identified upon arrival.

TRIAGE ACUITY RATING SYSTEMS

Based on an “across-the-room assessment,” brief interview, and focused examination, the triage nurse assigns an acuity rating. Historically a three-level acuity rating system has been used by most EDs. 13 The three levels are emergent, urgent, and nonurgent (Table 7-1). In an effort to better sort incoming patients, some hospitals added a fourth level to relieve the number of patients who were assigned to the middle or urgent level.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Emergent | Immediate care required; condition is threat to life, limb, or vision; “severe” |

| Urgent | Care required as soon as possible; condition presents danger if not treated; “acute” but not “severe” |

| Nonurgent | Routine care required; condition minor; care can be delayed |

A number of published research studies demonstrate the poor interrater reliability of the three-level triage acuity rating system. 16.29. and 30. Interrater reliability is the level of agreement or consistency among users of the system. As triage has evolved, there has been an increasing recognition that high interrater reliability is a necessary characteristic of an effective triage acuity rating system.

With the publication of research questioning the reliability of a three-level acuity rating system and concerns about ED crowding, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and the ENA convened a five-level triage task force to review the evidence on five-level triage scales. The following statement was developed by the task force and approved by the boards of directors of both ENA and ACEP:

ACEP and ENA believe that quality of patient care would benefit from implementing a standardized emergency department (ED) triage scale and acuity categorization process. Based on expert consensus of currently available evidence, ACEP and ENA support the adoption of a reliable, valid five-level triage scale. 14

As a result of this effort the Five-Level Triage Task Force recommended the use of either the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) or the Emergency Severity Index (ESI). 15

The CTAS, which is based on the Australasian Triage Scale, was developed by a group of Canadian emergency physicians working with the National Emergency Nurses Association (Canada). 2. and 3. All Canadian EDs use this five-level acuity rating system. The system mandates that every patient presenting for care should be at least visually assessed within 10 minutes of presentation. For each triage level there is a list of presenting complaints or conditions. The ED RN assigns acuity based on chief complaint and a focused subjective and objective assessment. CTAS identifies time to physician for each triage level but recognizes that meeting this time objective 100% of the time is not realistic. Accordingly, fractile response time, or the percentage of patient visits for a given triage level in which the patient should be seen within the CTAS time frame, is identified. 3 Reassessment times are identified for each of the five triage levels. Training materials are available from the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, http://www.caep.ca.

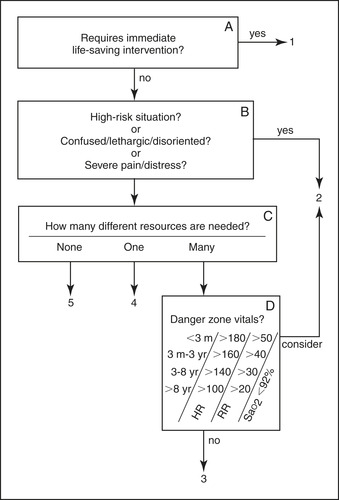

Two ED physicians, Richard Wuerz and David Eitel, developed the original concept for the Emergency Severity Index (ESI). Working with a group of emergency physicians and nurses, they made further refinements to the original algorithm based on research. The ESI is a five-level triage scale that categorizes patients initially by acuity and then by expected resource consumption (Figure 7-1). The algorithm is straightforward to use and allows for the rapid sorting of patients into one of five categories. Research has demonstrated that it is a valid and reliable system. Training materials that include the implementation handbook and training DVD are available free of charge from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, http://www.ahrq.gov/research/esi, or call 1-800-358-9295.17. 23.24. and 30.

|

| FIGURE 7-1 The Emergency Severity Index conceptual algorithm. (© ESI Triage Research Team, 2004. Used with permission.) |

THE TRIAGE PROCESS

The triage process is the rapid collection of relevant subjective and objective data in order for the triage nurse to assign an accurate acuity rating. It should be brief and occur soon after the patient arrives in the ED. The triage process begins with an across-the-room assessment. The triage nurse uses his or her sense of sight, hearing, and smell to gather vital information (Table 7-2) and form a general impression of the patient’s health status. 11.12. and 13. Occasionally the patient is so ill or injured that the nurse will recognize the patient needs to be seen immediately. At that point the triage process is over, and the patient is taken directly to the treatment area. This occurs in a small number of patients, and usually the triage process continues.

| COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. | ||

| Sense | Category | Examples or Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Sight | Sick or not sick | |

| Obvious deformities/amputations | Child with a craniofacial abnormality Severe kyphosis | |

| Method of arrival | Walked in Carried, wheelchair | |

| Body habitus | Tall, short Cachectic, thin, obese | |

| Dress | Appropriate Clean, disheveled | |

| Chronic illness | Bald due to chemotherapy Pursed-lip breathing from COPD | |

| Activity level | Walking with no difficulty Walking bent over, holding abdomen Using an assistive device (e.g., cane) | |

| Obvious blood on clothing, skin | ||

| Breathing | Obvious respiratory distress, working hard Using home oxygen | |

| Skin color | Severe jaundice | |

| Level of consciousness | Crying, moaning, laughing, talking, lethargic | |

| Hearing | Breathing | Wheezing, stridor, grunting |

| Speech | Tone, cadence, volume Language spoken, slurred | |

| Smell | Stool, urine, vomit | Incontinence, illness related |

| Ketones | Diabetic | |

| Alcohol, cigarettes | ||

| Poor hygiene | Living situation may need assessment | |

| Pus | Infection | |

| Chemicals | Exposure—skin, clothing | |

In a two-tiered triage system the first nurse is performing an across-the-room assessment, as well as determining the patient’s chief complaint. Based on this information, the first triage nurse decides whether this patient needs to be taken directly to the patient care area or is stable enough to go to step two of the triage process.

The Triage Interview

The patient is brought to a triage room or area where the triage interview can be conducted. The purpose of the interview is to gather additional information about the patient’s illness or injury. The triage interview should begin with the nurse confirming the patient’s identity, introducing himself or herself to the patient, and explaining to the patient the purpose of the triage process. For example, “Mr. Smith, my name is Sue. I am one of the emergency department nurses. I need to ask you a few questions about what brought you here today. Please have a seat, and take off your coat.” A friendly greeting and smile can go a long way to developing rapport with the patient and his or her family. Many are anxious and concerned about the patient, and a few words of reassurance will be appreciated.

The patient’s chief complaint should be documented in his or her own words and in quotation marks. Some patients need to be asked directly, “What made you come to the emergency department today?” “What made you call the ambulance?” Once the chief complaint has been determined, the triage nurse can proceed with a brief interview to elicit information about the chief complaint and relevant signs and symptoms.

Gathering appropriate subjective information is vital to making the right triage acuity rating decision. If the triage nurse does not clearly understand what the patient is trying to say, follow-up questions and clarification are needed. Obtaining information can be a challenge when the patient provides vague or global reasons for the visit: “I’ve been so sick,” or “My doctor told me to come here.” The triage nurse must focus his or her investigation on the history of the complaint and related symptoms and signs. The PQRST mnemonic is one example of a systematic approach to patient assessment (Tables 7-3 and 7-4).

| Component | Sample Questions |

|---|---|

| P (provokes) | What provokes the symptom? What makes it better? What makes it worse? |

| Q (quality) | What does it feel like? |

| R (radiation) | Where is it? Where does it go? Is it in one or more spots? |

| S (severity) | If we gave it a number from 0 to 10, with 0 being none and 10 being the worst you can imagine, what is your rating? |

| T (time) | How long have you had the symptom? When did it start? When did it end? How long did it last? Does it come and go? |

| Event | Triage Questioning |

|---|---|

| Minor burn | Cause or mechanism of the burn Location and depth of the burn Extent of the burnTreatment before arrival |

| Motor vehicle collision, not life-threatening | When did the event occur? Ambulatory at the scene? Speed of the vehicle Driver, passenger front or back Seat belt use, airbag deployed Vehicle damage Current complaints |

| Fall | When did this occur? Current complaintsFall—from what onto what? Why do you think you fell? (e.g., dizzy before fall) |

| Sports-related injury | Describe what happened Were you wearing a helmet or other protective equipment? Loss of consciousness? Ambulatory at the scene? Current complaints |

The triage nurse should use a variety of open (i.e., eliciting feelings and perceptions) and closed (i.e., “yes/no,” factual) questions to obtain information. Closed-ended questions are helpful for obtaining basic information such as, Do you have any allergies? To elicit details, open-ended questions are more effective. Restating, verbalizing observations, sharing information, actively listening, and summarizing are important communication strategies. The nurse’s style will vary with each patient and situation.

A medical interpreter should be used when the patient does not speak English or is more comfortable speaking in his or her native language. Many hospitals have medical interpreters on staff for non–English-speaking patients or have access to interpreters on call or via the telephone system such as the AT&T language line. Using family members can be problematic because you are asking the patient to share personal information with family members, and in addition, the family member may not understand exactly what you are asking. The triage nurse should document when an interpreter or family member was used to gather the history.

The triage process should take between 2 and 5 minutes. The triage nurse needs to be organized and efficient. It is important for the triage nurse to multitask or delegate to ancillary personnel specific tasks.

When sufficient information has been obtained about the chief complaint and related symptoms, the triage nurse may then obtain information about medications, past medical history, allergies, last menstrual period, and immunizations. Medication usage will include prescribed medications, over-the-counter drugs, herbal preparations, and home remedies.

At this point the triage nurse will perform a brief, focused physical examination based on the patient’s current injury or illness. The purpose of the examination is to gather additional information to support the triage nurse’s decision that this patient is safe to wait for care. The primary nurse will do a more in-depth assessment when the patient is taken to a treatment area. The triage examination is brief and should not require the patient to undress. It is not a head-to-toe assessment or a systems assessment but is a brief focused examination (Table 7-5).

| CSM, Circulation, sensation, and motor; ROM, range of motion. | |

| Chief Complaint | Focused Assessment |

|---|---|

| Short of breath | Respiratory rate, depth, effort Accessory muscle use Skin color Oxygen saturation Peak flow Level of consciousness Position Ability to talk in full sentences Abnormal sounds |

| Injured arm | Deformity, angulation Color, capillary refill, pulse Sensation Movement—ROM |

| Finger laceration | Wound length, depth, location Shape, swelling CSM, tendon involvement Evidence of foreign material Bleeding, bruising |

| Itchy eyes | Signs of inflammation, drainage Tearing, photophobia Visual acuity |

| Arm weakness | Level of consciousness Glasgow Coma Scale Facial symmetry Pronator drift Speech clarity and articulation Hand grasp strength Pupils—size and reaction |

Vital Signs and Triage

EDs have traditionally required a full set of vital signs on all patients as part of the triage process. Patients identified as unstable and in need of immediate care should be taken directly to an open treatment area. Care should never be delayed because a full set of vital signs has not been obtained. In some situations, vital signs may provide the triage nurse with additional information that will influence the acuity rating decision. Some EDs have chosen to assess and document a full set of vital signs on all lower acuity patients. Documentation of stable vital signs provides additional data to support the triage acuity rating. In one study of over 14,000 patients, vital signs changed the level of triage acuity in only 8% of cases. 6 Vital signs were found to be an important part of the triage process in the pediatric patient age 2 or younger, older adults, and those with communication issues. 6 The triage nurse needs to know normal parameters for age, the effect of medications, and certain disease processes (Table 7-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access