CHAPTER 7. Reducing resistance

• Introduction

• Three traps to avoid

• Three strategies for reducing resistance

• A case example of reducing resistance

• Conclusion

Asking the patient questions is not the best way to reduce resistance. However, it will be useful to ask yourself these questions instead! Remember, resistance is an observable behavior (e.g. denial, reluctance). It can be influenced by the goals you pursue and by the way in which you speak to the patient.

1 Have you undermined the patient’s sense of personal freedom? Can you hand this control back?

2 Have you misjudged the patient’s feelings about readiness, importance, or confidence? Have you jumped too far ahead of the patient on these dimensions? Are you focusing on the wrong dimension? Consider how this patient really does feel about change.

3 Are you meeting force with force? Are you being too confrontational? Can you do anything to go along with the patient, or even change tack altogether?

Introduction

Mrs. Green’s weight is a real problem. She says she would love to be slim. She is unresponsive, however, to any of your suggestions about healthy eating or physical activity. She does not accept that her weight is connected to her behavior in these areas; she says she hardly eats a thing and is always rushing around burning up energy. She is convinced the problem is ‘glandular’ or genetic in some way. You don’t know how to help when she won’t accept your suggestions.

Her husband, on the other hand, agrees with you that it would be good for him to be more active. However, for every good idea you have, he has a reason why he cannot do it. He hates ball games, he can’t afford to join a gym, walking to and from work is too dangerous in his neighborhood with the late shifts he does, and the pool isn’t open at hours that suit him.

Some patients seem to resist your best efforts to help them. You think you are making good progress and then it all gets difficult again.

The discussion that follows leans unashamedly on motivational interviewing, with the goal of identifying some of the most useful ideas that can be applied to brief consultations. The three practical strategies that follow are simply examples of the ways in which practitioners can respond to resistance. It is an area with rich potential for further development and research. This chapter focuses on generally applicable strategies. Later, in Chapter 9, we look at a range of problem consultations that could clearly benefit from further development work; for example, in talk about chronic pain or chronic fatigue syndrome where the levels of resistance can be very high. Other useful ideas can be found in the work of Egan (1994), who captures much of what is said in this chapter by noting, ‘Effective helpers neither court reluctance or resistance nor are surprised by it’ (p. 151).

What is resistance?

It is difficult to imagine a behavior change consultation that is not typically visited by resistance. It arises when there is tension or disagreement about behavior change. Since this can arise at any point in the consultation, it requires continual watchfulness. Its equivalent in dancing is the paying of attention to keeping yourself and your partner from stepping on each other’s toes. Maintaining a lightness of touch is essential.

The forms of resistance that emerge will vary across consultations and contexts. Sometimes, it takes the form of quiet reluctance in the patient; at other times, outright denial. In many healthcare settings, it manifests in quiet reluctance or apparent but unenthusiastic compliance, although scrutiny of talk about chronic fatigue syndrome reveals that it approaches the kind of overt conflict typically encountered in the addictions field. There is a tradition in some treatment centers for headstrong clients, embattled by years of conflict over their addiction, to meet their match; they are confronted by stridently directive counselors with ‘the problem’, and react with predictable defensiveness (resistance). One account of this process even referred to it as giving the client an ‘emotional haircut’ (Yablonsky 1989). Although healthcare practitioners, in our experience, seldom work in this way with patients, they can become battle-weary from too many frustrating encounters with difficult patients. Attitudes can harden: These patients are all the same. They simply don’t want to look after themselves. The danger here is that legitimate assessments about some patients harden into downright prejudice.

A common sequence is when the practitioner makes lots of helpful suggestions to the patient, Why don’t you… and the patient responds to each with, Yes, but… Practitioners then think they have not yet come up with a helpful enough idea and generate more suggestions, only to be met with more explanations of why each would not work.

In many healthcare consultations, there appears to be less outright conflict than in other settings, perhaps because time is shorter and patients do not have such a history of conflict with those caring for them. Patients are also sometimes in awe of doctors in particular, and do not feel assertive enough to argue outright, so the resistance is hidden behind unenthusiastic apparent compliance. Practitioners, for their part, sometimes tread a skillful path in order to avoid conflict (Butler et al 1998). Certainly, practitioners know that one way to avoid resistance is not to raise the subject of behavior change in the first place. This delicate management of resistance is well illustrated in the account of Silverman (1997), who describes quiet reluctance (e.g. Uhmm) from patients more commonly than outright rejection. The need to ‘save face’ by both parties is thought to be one explanation for this (Silverman 1997). We recently had the opportunity to listen to recordings of consultations about coughs, colds, and sore throats, where discomfort for doctors about whether or not to prescribe antibiotics is well documented in the literature (Bradley 1992). We found very little resistance, and reached the conclusion that both parties conduct a delicate dance around the subject of antibiotics. Patients are seldom asked outright whether they want this medication, and doctors often avoid mentioning the word. However, both parties know it is a central issue. In other words, the subject of resistance is not new to healthcare practitioners and patients; many are artful managers of tension in talk about change!

A description of various forms of resistance can be found in Chamberlain et al (1984): arguing can take the form of challenging, discounting, and outright hostility; denying can manifest in blaming, disagreeing, excusing, claiming impunity, minimizing, pessimism, and reluctance; and two other categories are interrupting and ignoring, which include behaviors like inattention, non-answering, and sidetracking (see also Miller & Rollnick 2002).

What causes resistance?

Resistance can arise when the patient brings conflict into the consulting room, when the practitioner elicits it, or as a result of a combination of the two.

The patient can be in a state of internal conflict about change in which different voices in the mind are pressing for different outcomes: I want to but it’s so difficult…; I may as well just carry on… If I could only try one more time… On the one hand, they want to change, and on the other hand, they want to hold back from doing so. The resistance side of the argument can arise from: It’s too difficult; The whole thing [condition] is out of my control; There’s a lot I like about the way things are now; I don’t like anyone telling me what to do.

When the patient is thinking privately about this, both sides of the argument are considered. They swing between It would be good to… and I really don’t want to. When they are in conversation with someone else, if the other person (e.g. the practitioner) takes one side of the argument, It would really help you if you could change…, the patient will naturally respond with the opposing view, But it’s not that easy. The same argument that was going on within the patient gets played out between the two of them, and practitioners frequently feel that they are fighting losing battles trying to help people who are just being resistant.

If the person is in conflict with others as well, it can be even more pronounced: She always nags me about my diet, but she’s the one who makes the food in the first place. What does she expect? And sometimes the person might not be in a state of conflict, but one of learned helplessness about lifestyle change. For example, some patients with chronic conditions like diabetes develop an almost habitual feeling of reluctance to change their lifestyles, and the routine check-up is characterized by reluctance from the patient and frustration for the practitioner. The more someone feels obliged to attend an appointment, the more likely it is that resistance will dog the consultation.

Whatever the personal source of resistance for patients, they will be particularly sensitive to the way in which they are spoken. Problems usually arise in the consultation when, wittingly or unwittingly, the practitioner, wanting to encourage change, elicits from the patient a voice for no change: Have you thought about controlling your diet? The bar is raised, and the stage is set for the emergence of resistance: Yes, but…

In some circumstances, resistance can arise in the complete absence of conflict in the patient, when it is only the practitioner who is concerned about change. For example, a heavy drinker with no associated medical problems and who has never thought about alcohol use as a problem is at the receiving end of a health promotion effort intended to minimize future complications. If the practitioner implies that alcohol use is a problem, resistance is a predictable outcome. More common, we suspect, is where the origin of resistance is not as extreme as in this example, and there is an interaction between the conflict experienced by the patient and the motives and consulting behavior of the practitioner. Thus, whatever its origins, resistance cannot be defined outside of this interpersonal context. The practitioner has the potential to lower or raise the level of resistance.

Dealing with resistance

It is unrealistic to view resistance as a sign of failure in the consultation, as something that is abnormal and that should be eliminated from the discussion at all costs. Some therapists even say that with good rapport, resistance provides the kind of energy that generates change. However, in most time-limited healthcare consultations, it is a nuisance. Hence our view is that, on an ongoing basis, practitioners should look out for resistance and move towards reducing it. This is not just a matter of what you say, or what strategy you use, but how you say it, and being in a flexible state of mind in which you roll with resistance (Miller & Rollnick 2002) and avoid argument.

Three traps to avoid

Three traps have been isolated for particular attention, each giving rise to a strategy for avoiding it, described below. Fall into any of these traps and resistance will be a likely outcome.

Take control away

We all know some patients who are very compliant and like to be told what to do. Most, however, do not respond well to this. Strategy 1 below (emphasize personal choice and control) illustrates how one can avoid this pitfall in a consultation.

Misjudge importance, confidence, or readiness

This is a very common trap to fall into. For example, one can focus prematurely on change when the patient is not ready for this, or one could focus on importance when the patient is actually more concerned about confidence matters. Strategy 2 below (re-assess readiness, importance, and confidence) involves re-examining the patient’s feelings about these issues, to make sure that one remains aligned to his or her needs.

Meet force with force

Whatever the topic of conversation and whoever the patient is, confronting resistance with force will make matters worse. A good consultation is not like a wrestling contest! However, use of Strategy 3 below (back off and come alongside the patient) will demonstrate that the rewards of avoiding confrontation are liberating, even though this is the most skillful of the strategies to execute.

If the consultation begins to feel like a battle, and you feel as if you are going all out to win, there is a problem. People will defend themselves better the more they feel attacked. They will become deeper entrenched in their position. If you do win, will the patient feel they have lost? Is this the outcome you really want?

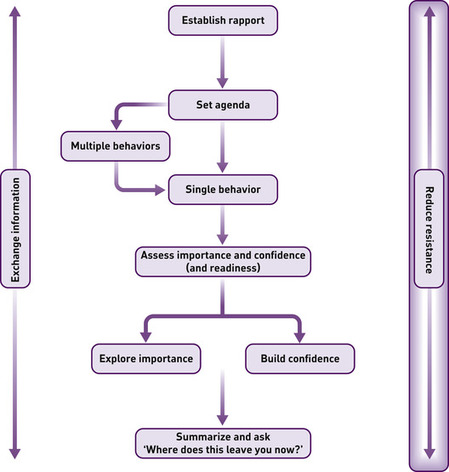

Three strategies for reducing resistance

Three options described below are:

• emphasize personal choice and control

• re-assess readiness, importance, or confidence

• back off and come alongside the patient.

Strategy 1. Emphasize personal choice and control

If a person is struggling to maintain some sense of control over his or her life, it does not take much to threaten this sense of stability. All one needs is a confrontation with a practitioner and resistance to change will emerge. It does not take much to fall into the trap of undermining the personal autonomy of the patient. Statements like You should do… or The biggest problem you have is… are likely to have this effect, because they restrict the person’s sense of freedom and will elicit resistance in the form of re-assertion of autonomy (see Miller & Rollnick 2002). Every parent knows this problem; if you say to a young child, You are dirty and you should go and wash now, the almost instinctive reaction will be a form of resistance, which has more to do with personal autonomy being undermined than with the content of your statement. The content, for example, a response from the child like, But I’m not dirty, merely provides the stage on which the battle for autonomy is played out.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access