CHAPTER 7. Forensic Photography

Georgia A. Pasqualone

Historical Background

Alphonse Bertillon (1853-1914) was a French law enforcement officer, biometrics researcher, and criminalist who was the first person to incorporate photography with an identification system called bertillonage. His photograph cards of criminals and suspects, representing the foundations of our present-day “mug shots,” contained demographic information suitable for use in criminal investigations. This new concept of using photography in police work spread quickly from Paris throughout the world. In 1859, photographic enlargements were introduced to the court system with a case that involved a dispute about questionable and known handwriting signatures contained within a land grant (Moenssens, Starrs, Henderson, et al., 1995). Finally, in June of 1871, photographs were used for the first time as pieces of crime scene evidence. The consequences of this event resulted in the world bearing witness to incriminating photodocumentation of the Paris police massacring the Communards at the end of the Franco-Prussian War (Sontag, 1977). Since that time, photographs have been utilized by many different types of healthcare professionals around the world.

Nurses, by virtue of their job descriptions, are all occupational photographers. In other words, the camera has become a valuable tool, as serviceable as the stethoscope or syringe. The camera has now become an extension of the nurse’s eyes. Through photodocumentation, time can be stopped and history captured. Such a worthwhile and valuable practical tool is crucial to incorporate into the clinical practice of all forensic nurse examiners. Forensic nurse examiners are in the position of being objective scientists, and photography is fast becoming a supplemental form of documentation that must augment our work responsibilities. There is no question that the nurse’s first duty is to provide lifesaving treatment for the trauma victim, but the patient and society are ultimately best served when the nurse can also recognize and preserve evidence that may later be used in a forensic investigation.

Exigent Evidence

Along with performing the ABCs of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, forensic nurses must realize that photography should become an automatic function of all trauma protocols. It is not only the trauma victim who needs this instant attention. Certain forensic situations aside from trauma require the immediate responsiveness of photodocumentation. These situations are called “exigent.” Exigent and exigency are terms used within the legal system and translate to mean that, for whatever reasons, information must be obtained now and not at a later time. Exigent evidence can be lost in seconds. It can be washed off, thrown away, flushed down drains, or it may leave with a patient, friend, or family member. Therefore, nurses must realize that evidence is exigent.

One of the foremost examples of exigency and liability is child abuse. Nurses may become suspicious of a parent’s or other caretaker’s story, wanting to photograph injuries on the child. When consent is requested, parental refusal can create a very uncomfortable and difficult situation. Photographing the injuries is critical because the surface wounds will heal or, worse, the child may die as a result of those wounds. Lack of proper photodocumentation in such circumstances could allow claims that the event never occurred, allowing the perpetrators to go uncharged. For this reason, nurses may have to justify their decision to photodocument without prior consent in court. If the nurse can justify that the photodocumentation of evidence had to be done immediately because the evidence could have been destroyed or lost, no judge should find that nurse liable. Photodocumentation of such injuries can lock events into a proper chronological sequence that can then be used for litigious review. In the past, photographs and x-rays have been the focal point during a child abuse case where the observed injuries and the caretaker’s story may not have matched, thus demonstrating the presence of injuries in various stages of healing. If a nurse acts in good faith in photographing a child’s injuries, yet the court determines that no exigent circumstances were present, the photographs will usually not be allowed and there should be no repercussions against the nurse.

Justice is best served by objectivity. When attorneys, judges, and juries can evaluate photographs, along with the proper accompanying written documentation, the entire medical system is better protected from wrongful accusations. Photographing injuries in litigious situations protects healthcare professionals from allegations that patients or clients never received the proper care. For example, if a person claims to have slipped and fallen on a patch of ice or in a tangle of wires, the environment must quickly be photodocumented before changes occur to that primary scene. Photography is capable of capturing moments in time and preserving events for future reference.

Camera Basics

The word photography comes from two Greek words meaning “writing ( graphe) with light ( photos).” It is the process by which light is used to create a picture. Four basic elements are required in order to make that picture: the camera, lens, film, and light. Today’s digital technology can replace film with memory cards and electronic storage devices. Regardless of the technology, all four of these components can be built into one unit in which they are preadjusted to a single setting and activated by pushing the shutter button. However, the four separate entities can also act individually so that every factor can be controlled independently. Therefore, each of these four components will be discussed, as well as some other important photodocumentation concepts, to explain how they all contribute to the taking of a photograph.

The camera

A camera is nothing more than a light-tight box with a round hole in the front for the lens and a hinged door in the back or bottom for the insertion of either the film or the memory card. Understanding the simplicity of this concept should ward off any fears about handling new photographic equipment. Any further mystery surrounding the camera can be explained by reading the operator’s manual and keeping it at hand for ready reference.

Healthcare professionals have the choice of using three distinct camera systems in the forensic setting. These systems are distinguished by their viewing system or by the way in which they visualize the subject. All other systems tend to be too complicated, too large, or otherwise inappropriate for the purpose of medical or crime scene photodocumentation.

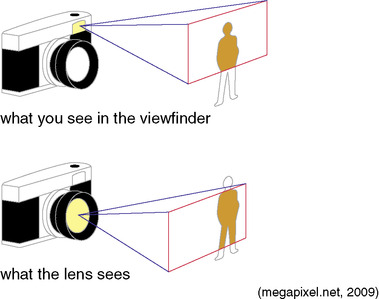

The first system is the older, more conventional method, known as a single-lens reflex camera, commonly abbreviated as an “SLR.” The SLR allows the photographer to look through the viewfinder to “see” exactly what will be reproduced on the film. It has a “what-you-see-is-what-you-get” viewing system. The second visualization system is referred to as a rangefinder or point-and-shoot (P&S) camera. In this system, the viewfinder is placed near the lens so that the photographer’s view and the camera’s view are close but not exactly the same. With this system, there is the potential for chopping off the top, bottom, or one side of the subject in the photograph. This situation is commonly referred to as parallax. The problem of parallax becomes worse as the camera gets closer to the subject and becomes actually crucial when photographing close-up images of injuries. For this reason P&S cameras are not preferred for photodocumentation in the emergency department (ED) clinical setting. Unfortunately, most people prefer a P&S camera because of its ease and simplicity of adjustments to whatever is seen in the viewfinder operation. However, with a P&S camera, the necessary adjustments must be made on a specific geometrical plane (e.g., left and right, and top and bottom shifting) while composing the image in the viewfinder. Therefore, in the clinical setting when time is critical, it is desirable to use the SLR viewing systems in which the parameters in one’s field of vision are precisely what is captured on film (Fig. 7-1).

The third and most popular system being utilized by the forensic photographer is digital. Digital cameras are one of the most versatile pieces of equipment that the forensic photographer can use today. Digital makes film obsolete, produces more images than a canister of film could ever hold, provides an image preview through the liquid crystal display (LCD) screen, and gives the photographer immediate feedback of what is being visualized. Prices for various models of digital SLRs (DSLRs) are comparably priced with the conventional SLR and P&S equivalents. Also, the more sophisticated the model, the more expensive the camera and lenses are going to be (Fig. 7-2).

The conventional camera systems are further subdivided by the film formats they use. One type is the 35 mm. In this system, the film canister must be removed from the camera to be processed. A negative is produced and any number of prints and enlargements can be made from that negative with further processing. The second type is the “instant,” self-developing film. The photograph is produced within minutes of exiting the camera. There is no negative, and any copies and enlargements must be created by other means outside the system.

The instant camera system is an almost foolproof method for certain crime scenes and clinical situations. When only a few photographs are needed to document an injury, the instant photograph is a quick solution. Known by its proprietary name, Polaroid, the instant camera system made its debut in 1947. After more than 50 years of innovative improvements, Polaroid provides the closest thing to the P&S camera concept without the parallax error. As of 2008, the Polaroid Corporation ceased manufacturing the instant camera systems as well as the film for these cameras. However, for as long as there continues to be a stockpile of film, there will be institutions that may still incorporate the instant camera systems into their photodocumentation protocols. Until that time, the instant camera system may be considered easy and practical.

The lens

The human eye is the equivalent of the lens on a camera. The lens is the window of the camera through which light and the image of the subject travel before imprinting on the film. The quality of the glass and the optics in the lens determine the quality of the resulting photograph. There are two basic types of lenses: fixed and interchangeable.

Fixed Lenses

Fixed lenses are available on all the simpler cameras such as the P&S, the instant camera systems, and the basic digital cameras. They cannot be removed from the camera body, and the photographer has little or no control over how that lens is used. Fixed lenses also have a preset focal plane. This means that the photographer cannot focus on any subject closer than 2½ to 4 feet away. This restricts the capability to take close-up photographs. If the photographer is required to remain 4 feet from the subject, the composition of the photograph changes, and more background is included than desired, thus distracting from the intended subject.

Interchangeable Lenses

Interchangeable lenses are most commonly used on SLR cameras and the higher-end digital cameras (DSLRs) and allow the operator to pick various lenses to suit the situation or need. The ability to choose between different lenses allows the operator to accommodate for changes in focal length, depth of field, and various lighting situations. Interchangeable lenses can be removed or attached to the camera with both a threading and screwing mechanism or with a bayonet system. The bayonet mounting system attaches a lens to the camera by first aligning marks on both, inserting the lens, and then twisting the lens to lock it in place.

Lenses are categorized by a number expressed in millimeters (mm), which represent the lens’ focal length. Focal length is the distance measured from the center of the lens to the film plane and determines the field of vision seen through the lens. The most common lens is the 50- mm, or normal lens. The normal lens has a perspective similar to that of the human eye.

Lenses less than 50- mm are known as wide-angle lenses. The 28-mm lens is one of the most common. Wide-angle lenses give a wider view of things than only scanning one’s eyes or moving one’s head from side to side would provide. Wide groups of people, an entire room with its contents, and greater portions of crime scenes are better photographed with wide-angle lenses.

Lenses greater than 50 mm are known as telephoto lenses. Telephoto lenses work similarly to a telescope, enabling the subject to be closer to the photographer without moving him or her or the camera closer to the subject. They also make certain close-up tasks easier to achieve, especially when photographing injuries on an assault victim. The lens brings the injury closer to the photographer without invading the victim’s personal space.

Zoom lenses have variable focal lengths and can adjust to distances by simply moving the telescoping mechanism of the lens forward and back. An excellent choice for a one-lens purchase would be a 24- to 140-mm zoom. This lens would accomplish all wide-angle through telephoto needs in one step. If expense is a major issue, a more economical range would be a 28- to 105-mm lens or a 35- to 70-mm lens.

Close-up and macro lenses are both convenient and necessary for detailed work because they allow the photographer to focus a few inches or centimeters away from the subject. For most forensic nursing applications, the terms close-up and macro will be synonymous. Close-up photography can mean anything from one-quarter life-size (1:4 or .2×) to a 5× enlargement, depending on the equipment and the available attachments. A 2× enlargement will give a head and shoulders view of the subject (Fig. 7-4). An example of a 5× enlargement would be a photograph of an eye magnified large enough to enable one to count the eyelashes and the blood vessels on the sclera (Fig. 7-5). With colposcopy, the subject matter is magnified up to 30×. (See Chapter 13 for more on colpophotography.)

The film

Film is one of the oldest mediums used to record the image of the subject. There are still many film types on the market, and there are specific films for specific functions.

Color negative film has been the most versatile and, therefore, the most popular. There are various sizes and types of film, corresponding to the size of the camera in which it will be used. A forensic nurse will predominantly use 35-mm film in an SLR camera. The number of exposures per canister roll can vary from 8 to 36. The reproduction ratio of pictures is 2:3. This means that the dimensions of the resulting photograph should reflect the same ratio: 4 × 6, 6 × 9, 8 × 12, 16 × 24, and so forth. Before the “jumbo print” phenomenon, the older version of the print size was 3½ × 5 inches. This means that for many years, a good portion of the photo was being trimmed off. Therefore, for the photo to be enlarged to the proper proportions without any of the edges being cropped, the operator needed to request that the negatives be printed “full out” or “full frame.” For example, the popularly accepted 8 × 10 loses 2 inches off the 10-inch edge of the photograph. “Full frame” will produce an 8 × 12 print with the subject intact.

All film has an expiration date stamped on the outside of its box. It is vital that an operator not use expired film for photodocumentation of injuries when color is a crucial matter. It is important to store film in a cool, dry place. Personal experience has proved that, if stored correctly, there is a safety net of 6 months to 1 year for most films. If storing film in the refrigerator, maintain humidity at a minimum. Allow the film to stand and attain room temperature before loading it into the camera. Process the film as soon as possible after it is exposed. If this is not possible, simply continue to keep the film cartridge cool and dry. Never store film of any kind in a hot car during the summer months. Heat changes the chemical emulsion and greatly affects color.

Light and flash

There are two physical aspects concerning light that every photographer must remember. The first is that light travels in a straight line. The second is that there are varying intensities of light. Therefore, to use light to the best advantage, it must be provided, controlled, reflected, and bounced. The goal is to produce a photograph that accurately duplicates reality. The photographer must be able to testify that a photograph is a true and accurate depiction of the original scene as it was on the day in question.

There are two basic types of light: available and artificial.

Available Light

Available light, also known as ambient light, is the surrounding, existing light that is illuminating a particular room at a particular time, no matter what the source. It is the lighting inside a room, store, restaurant, train station, tunnel, or examination cubicle. The disadvantage of photodocumenting using only available light is that it is usually much dimmer than outdoor sunlight. Without the use of high-speed, low-light films, the photographer might have to rely on a tripod and slower shutter speeds in order to obtain correct exposure of the subject.

Artificial Light

Artificial lighting, which is illumination produced by other than natural sunlight, may also affect the color quality of the film used. Fluorescent lighting, frequently found in hospitals and medical examiner’s offices, tends to give photographs a yellow to green hue. This can be eliminated only with the use of a light source brighter than the fluorescent lighting itself, or the electronic flash. In the majority of contemporary flash units, there are special sensors called thyristors, which are part of the electrical circuitry of the flash unit itself. Thyristors electronically calculate the amount of light that is required to correctly illuminate a subject. For instance, if the subject is close, the flash will not be used to its fullest intensity. This results in a faster recycle time for the next shot and conserves the life of the battery.

Under most circumstances, the photographer must supply artificial lighting. This can be done via a flash unit built into the camera or an external light source. Flash units built into a camera are limited with respect to any photographer control. Most consist of a direct flash that goes from the camera straight toward the subject. In some instances, the flash may be turned away to bounce off another object such as the wall or ceiling. An external flash or light source usually gives the photographer more control of both intensity and direction of the light. With the ability to control the various aspects of lighting, subsequent photographs are usually better exposed. The only drawback is that it also makes the equipment bulkier.

Specialized lighting sources are available to be used with some cameras. Ring-light flashes are utilized with close-up photography to provide even lighting for dimensional subjects as opposed to harsh illumination or washouts. Ring lights are usually standard equipment on the colposcope and are invaluable in lighting anogenital injuries.

Most contemporary autofocus 35-mm SLR cameras have a dedicated flash sensor built into the camera. It is not necessary to set the shutter speed to accommodate the flash because the camera automatically measures the light that reaches the film. On contemporary cameras with liquid crystal displays (LCD), verify that the camera is set for this type of automatic metering. In fact, always check the settings on all manual, digital, and LCD panel cameras before photographing any assignment.

• Direct flash. Direct flash can be harsh, especially if it is too close to the subject. The flash can wash out detail, creating a “white out” or “hot spot” in the middle of the photograph. By bouncing the light from the flash, it becomes less harsh and still illuminates the subject adequately. This technique also makes it possible to document fine detail in scars, tool marks, and anything that mandates recording depth or dimension. Most digital cameras have a direct flash capability and the result is a white out if positioned too close to the subject. It is optimal in these circumstances to use the higher-end DSLR, which also has a “hot shoe” for connecting a separate flash unit to the camera and bouncing it off the ceiling. If direct flash is the only option, diminish or “soften” the light source by placing a thin layer of tissue or gauze over the flash on the camera. Be careful not to obstruct the lens during this process.

• Bouncing flash. Bouncing a flash means that the light coming from the flash is not aimed directly at the subject but at the ceiling or the wall behind the subject. This technique eliminates harsh shadows and red eye. Bouncing flash relies heavily on the color and height of the ceiling, affecting both subject lighting and color accuracy. There is a simple solution to this problem. Place a white card on the back of the flash so it faces the subject. It can be secured with a rubber band. When light is bounced off the ceiling, the card reflects some of it forward into the dark recesses of shadow, whether on a face, around a fine scar, in a tire impression, or on tool marks made by a screwdriver to pry open a window. This bounce technique will be successful because the autoexposure mode of the flash is still working to determine the correct amount of light necessary for proper exposure (Fig. 7-6).

There are several ways to solve lighting issues in the clinical setting such as using secondary flash units or additional lights to prevent shadows. Use of a faster film speed will also help to accommodate for some lighting problems.

When taking full-length and intermediate photographs of patients in the clinical setting, the availability of equipment may be at a minimum. To increase control of the light from the flash and to eliminate harsh shadows behind the patient, place the patient in a corner. The light will bounce off the two opposing walls and illuminate the sides of the patient’s face as well as eliminate the dark shadows behind the head that are created when shooting directly into the patient’s face.

“Red eye,” which is caused by the reflection of the flash on the blood vessels on the retina, can be prevented by increasing the distance between the flash and the camera lens. This is one of the applications for an off-camera flash unit, synchronized to the opening of the camera’s shutter with an extension cord. Two practical ways to diminish “red eye” are to either have the patient look away from the camera lens, or to increase the lighting in the room so that the patient’s pupils are more constricted.

Shutter speed

The shutter of a camera is the mechanism that opens, closes, and determines the amount of time that light is allowed to reach the film. The shutter speeds of P&S cameras are preset at either 1/60th or 1/125th of a second and cannot be changed. DSLRs and conventional SLRs have variable shutter speeds that range in time from 1/1000th second up to 1 second. Setting the camera on “B” for bulb will allow the photographer to take a timed exposure. This means that the shutter is left open for any period of time greater than one second, determined by the photographer for the correct exposure. Today, some cameras have an equivalent “T” for time setting. The longer the shutter remains open, the longer the subject and the photographer must remain still, as movement will create a blur on the image.

Aperture

The beam of light that enters the camera and reflects on the film is controlled by an adjustable opening in the lens called the aperture. The aperture is known by many other names, such as lens opening, iris, diaphragm, f-number, or f-stop. The aperture is an iris-like diaphragm, similar to the pupil of the human eye, which provides a variable-sized hole that regulates the amount of light passing through the lens. A lens is identified according to the f-number that corresponds to its widest lens opening. The widest lens opening has the optimal light-admitting capacity. The f-stop is controlled manually by a movable ring surrounding the lens (Fig. 7-7, Fig. 7-8 and Fig. 7-9).

Depth of field

Depth of field refers to an area both in front of and behind the subject that is in acceptably sharp focus, usually 7 through 13 feet. The depth of field can be increased by decreasing the size of the lens aperture. By closing the aperture, a longer shutter speed will be required to produce the same amount of light needed to reflect on the film.

Three principles of depth of field should be used as a reference:

1. The depth of field doubles if the f-stop is doubled (i.e., from f/8 to f/16).

2. Doubling the subject distance will increase the depth of field fourfold. Triple the distance, and depth of field will increase ninefold. Decreasing the camera to subject distance will decrease depth of field.

3. Reducing the focal length by one half will increase the depth of field fourfold (Fyffe, undated).

One of the greatest challenges requiring depth of field knowledge is a situation in which the community health nurse must photodocument vast quantities of both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications in the home of a client who has just expired. It is imperative to focus clearly on the patient’s name, the names of the medications, and the names on the pharmacy labels. Stopping down to f/22 is not unusual, remembering that the shutter speed must also be readjusted to a slower speed to accommodate the diminished light coming through the lens. It might be necessary to use a tripod to ensure stability for those longer shutter speeds. A shutter speed of 1/15th of a second is also not unusual in these instances. Remember, too, that flash attachments might not be synchronized for the slower shutter speeds and, therefore, may not be an option in this particular case if close-up identification is to be made of the bottles (Figs. 7-10 and 7-11).

|

| Fig. 7-10 |

Filters

The lens on a camera is placed in some potentially hazardous positions. It may collide with objects or even be dropped on the floor. The most economical way of protecting the lens is by purchasing an ultraviolet (UV) filter (also known as a skylight, or haze filter). The UV filter is fitted over the lens and absorbs only ultraviolet rays; it does not affect the photographs and should be kept on at all times.

The second lens necessity is a circular polarizing filter. Polarizing filters reduce glare and haze and remove distracting reflections from nonmetallic glossy surfaces including water, glass, plastic, and highly polished leather and wood. The filter attaches directly to the front of any interchangeable lens. This type of polarizer consists of two rings, one that threads onto the lens, and another that spins to control the degree of polarized effect. Using the viewfinder, rotate the filter until the reflection or glare on the subject disappears. Be careful to rotate only the distal end of the filter to avoid accidental detachment.

Proper use of the polarizing filter includes knowing when to use it. If standing at an angle to a body of water or a store window, the reflections can be removed enough for the photographer to be able to see beyond and under the surface of the water or through the window. Photographing the vehicle identification number (VIN) of an automobile requires shooting through the windshield. However, the sun may be reflecting on the window or one’s own reflection may appear in the glass. Using the polarizer will eliminate the unwanted glare as well as reflections in the photograph.

Colpophotography

Colposcopy is another photodocumentation technique used in investigation. The colposcope is an instrument consisting of a light source, variable magnification binoculars, and a camera. It was developed initially for visualization of the adult cervix, but it has become invaluable in the detailed examination of both adult and child genitalia in incidences of sexual abuse (see Chapter 13). An accurate photographic record of the examination will provide invaluable evidence and may eliminate the necessity for a victim to be reexamined if a second opinion is needed.

One of the first documented forensic applications of the colposcope was in 1981 by a Brazilian physician, Dr. Wilmes Teixeira, who utilized it as part of the examination of adult sexual assault victims. Five years later, in 1986, Woodling and Heger reported their findings on colposcopy use during examinations of pediatric sexual abuse patients. Although colpophotography is traditionally a gynecological and sexual assault technique, there are alternative uses. It most certainly can be and should be used in the photodocumentation of bite marks anywhere on the body or any other microscopic or questioned injury (Fig. 7-12).

|

| Fig. 7-12 (Courtesy CooperSurgical/Leisegang.) |

The colposcope provides illumination and magnification for the examination of the lower anogenital area of both adults and children. It is a stereoscopic or binocular device with variable features, which include magnification from 5× through 30×, up to a 150-watt halogen ring-light source for bright illumination, a 300-mm objective lens, and 35-mm photographic capabilities. The ring-light flash surrounds the objective lens. The magnification systems have multiple settings or may have zoom capability. The camera used can be either the 35-mm or digital SLR, usually with a data bank, which automatically imprints the time, date, and an identification number directly on the photograph. The camera may remain mounted on the scope even when photodocumentation is not desired.

In colposcopic photography, the light meter on the SLR should show the photograph as being somewhat underexposed. This underexposure is necessary to compensate for ambient light and to ensure the highest quality photographs possible. With practice, the examiner can perfect the techniques needed for optimal photographs. The following guidelines may be helpful:

• The colposcope has a limited depth of field. The colposcope should be no more than 10 to 12 inches from the subject. Most images should be taken at 6× and 10× for the best depth of field and field of view.

• What is seen in the monitor and through the scope is not what the camera sees. Before snapping the picture, look through the viewfinder to ensure the subject is in focus and the field of view is correct. Don’t forget to look through the camera with the dominant eye. The dominant eye is the one in which the best focus and clarity are seen.

• The higher the magnification, the more light is needed.

• If still using 35 mm, be sure to bracket each picture to allow for over- and underexposure. Not all film is equal! The brand of the film may affect the quality and color balance of the photograph.

• Be certain to document the magnification level for each picture.

• Photographs should contain a 7% gray scale with color guide in at least one picture per roll of film (Price, 1999).

Color scales and 7% gray rulers are available to both healthcare professionals and law enforcement officials through evidence collection and equipment supply companies. A 7% gray card reflects approximately 7% of the light to which it is exposed. Use of the gray card and color scale helps determine a comparison of true color and also the tones of gray between black and white in the photographs being entered as evidence.

Electronic storage and retrieval of digital colposcopic images is an extremely practical tool. The technology allows the physician to transmit any suspicious images from remote satellite clinics to major medical centers for telemedicine conferences. The physician can keyboard in an electronic report of the findings, including full-color pictures, before the patient is off the examination table.

Digital Photography

Digital photography electronically captures an image through the use of a filmless camera. Other than the absence of film, the physical features of the digital camera are relatively similar to the SLR 35-mm camera. The higher-end cameras still use lenses, aperture, and a shutter at varying speeds, depending on the availability of light. Instead of film, the camera records an image on a charge coupled device (CCD) or a complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS). The CCD chip has a light-sensitive surface. The light-sensitive surface can be equated to the American Standards Association (ASA) or International Standards Organization (ISO) of film. The sensitivity of the chip can be increased just as the sensitivity of film can be increased. The CMOS also has a light-sensitive surface but consists of a technical architecture that reduces the area on the chip for capturing light, resulting in less uniformity. Check with the manufacturer specifications for the chip details.

The image, once it is recorded, is then stored inside the camera on a computer disk or storage device. It can then be transferred, or downloaded, at a later time through the use of a computer and electronic technology. One of the storage devices can be the computer’s hard drive. If a disk is used for storage, the disk can be removed from the camera, installed into a personal computer (PC) or laptop, and instant images are available. The images themselves can be downloaded to a color printer, e-mailed to other computers, or simply be viewed on the computer screen or a television set in a matter of minutes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access