Care of Patients with Pain

Objectives

2. Review the gate control theory of pain and its relationship to nursing care.

3. Compare nociceptive and neuropathic pain and the nursing care for each.

4. Explain how pain perception is affected by personal situations and cultural backgrounds.

6. List the different pharmacologic approaches to pain management with examples of each.

7. Analyze the major differences between acute and chronic pain and their management.

1. Effectively use the nursing process for pain management.

2. Use appropriate pain evaluation tools for a variety of patients.

3. Recognize common side effects of analgesics and describe techniques for addressing them.

4. Employ nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management with a variety of patients.

Key Terms

acute pain (ă-KŪT pān, p. 127)

adjuvant (ĂJ-ŭ-vănt, p. 126)

buccal mucosa (BŪK-ăl MŪ-cō-să, p. 136)

chronic pain (KRŎN-ĭk pān, p. 127)

endorphins (ĕn-DŎR-fĭnz, p. 125)

epidural (Ĕ-pĭ-DŬ-rŭl, p. 136)

intractable pain (ĭn-TRĂC-tă-bŭl pān, p. 136)

modulation (p. 126)

neuropathic pain (nū-rō-PĂTH-ĭk pān, p. 126)

nociceptive pain (nō-sē-SĔP-tĭv pān, p. 125)

pain threshold (pān, p. 127)

pain tolerance (pān TŎL-ŭr-ŭns, p. 127)

perception (pĕr-CĔP-shŭn, p. 126)

phantom pain (FĂN-tŏm pān, p. 126)

placebos (plă-SĒ-bōz, p. 134)

referred pain (rĭ-FŬRD pān, p. 130)

transduction (trănz-DŬK-shŭn, p. 126)

transmission (trăns-MĬ-shŭn, p. 126)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Theories of Pain

Current thinking views pain not as just a symptom, but as a specific problem that needs to be treated. Pain is defined as a neurologic response to unpleasant stimuli. Pain receptors are abundantly distributed throughout the skin and in many deeper structures of the body. Receptors for pain do not become dulled with repeated stimulation and, under some conditions, repeated stimulation results in an increase in the acuteness of the pain sensation.

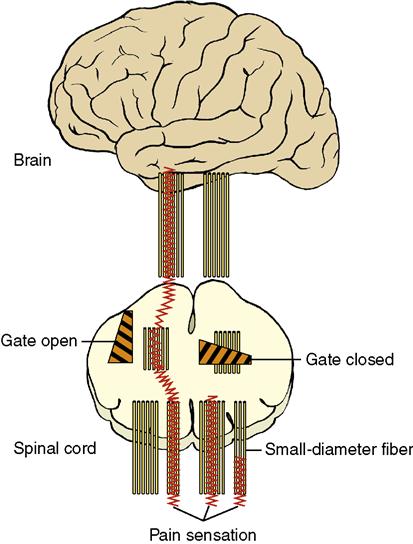

Pain results from the release of various chemicals from damaged cells, but the actual mechanism of pain is still poorly understood. It may be helpful to think of pain as being controlled by a “gate” in the central nervous system (Figure 7-1). When the gate is open, the pain sensation is allowed through. When the gate is closed, the pain sensation is blocked. The gate control theory recognizes that stimuli other than pain pass through the same gate. When a large volume of nonpainful stimuli are competing for the gate, pain impulses may be blocked. A high volume of pain, however, may override other stimuli and pass through the gate, causing the individual to perceive the pain.

Aspects of this theory relate to nursing practice in several ways:

• Two types of nerve fibers—small-diameter and large-diameter—carry pain stimuli.

• Massage and vibration produce activity in the large-diameter nerve fibers.

Another way of looking at pain and its management is the idea of “pieces of pain.” The more intense the pain, the greater the number of pieces, and therefore a greater number of pieces of analgesia will be required to control pain. This idea states that inadequate analgesia results in leftover “pieces” of pain, and total relief or control has not been achieved.

The human body produces substances called endorphins (endogenous morphine) that attach to pain receptors and block pain sensation. Much is still unknown about endorphins and how they work, but their properties appear to modify and inhibit unpleasant stimuli, reduce anxiety, and relieve pain. Endorphins also may produce feelings of euphoria and well-being. For example, the “runner’s high” may occur because endorphins are released after physical exercise.

Classification of Pain

There are two pathophysiologic classifications of pain: nociceptive and neuropathic.

Nociceptive Pain

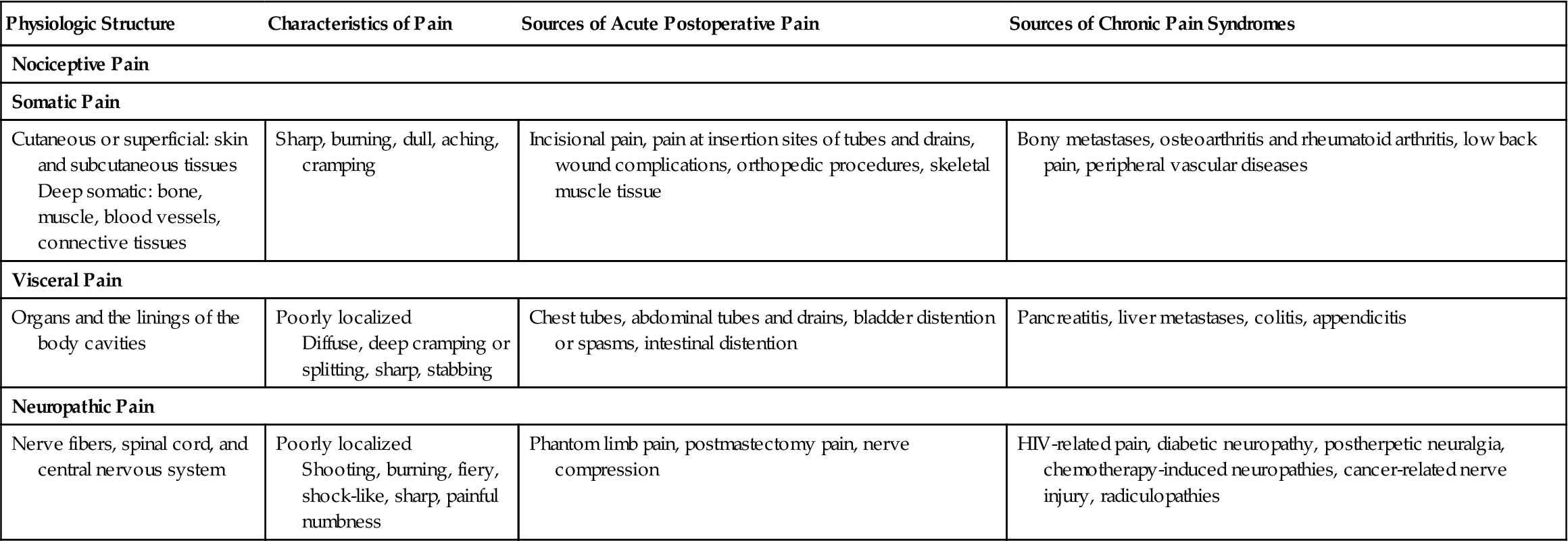

Nociceptive pain is associated with pain stimuli from either somatic (body tissue) or visceral (organs) structures. Somatic nociceptive pain arises from injury to tissue where pain receptors called nociceptors are located. These nociceptors may be found in skin, connective tissue, bones, joints, or muscles. Trauma, burns, or surgery may cause injuries triggering somatic nociceptive pain. Visceral nociceptive pain arises from pathophysiology in visceral organs such as the organs of the gastrointestinal tract. Pathologic conditions triggering visceral nociceptive pain include tumors and obstructions of the organs (Table 7-1).

Table 7-1

| Physiologic Structure | Characteristics of Pain | Sources of Acute Postoperative Pain | Sources of Chronic Pain Syndromes |

| Nociceptive Pain | |||

| Somatic Pain | |||

| Cutaneous or superficial: skin and subcutaneous tissues Deep somatic: bone, muscle, blood vessels, connective tissues | Sharp, burning, dull, aching, cramping | Incisional pain, pain at insertion sites of tubes and drains, wound complications, orthopedic procedures, skeletal muscle tissue | Bony metastases, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, low back pain, peripheral vascular diseases |

| Visceral Pain | |||

| Organs and the linings of the body cavities | Poorly localized Diffuse, deep cramping or splitting, sharp, stabbing | Chest tubes, abdominal tubes and drains, bladder distention or spasms, intestinal distention | Pancreatitis, liver metastases, colitis, appendicitis |

| Neuropathic Pain | |||

| Nerve fibers, spinal cord, and central nervous system | Poorly localized Shooting, burning, fiery, shock-like, sharp, painful numbness | Phantom limb pain, postmastectomy pain, nerve compression | HIV-related pain, diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, chemotherapy-induced neuropathies, cancer-related nerve injury, radiculopathies |

Adapted from Ignatavicius, D.D., & Workman, M.L. (2010). Medical-Surgical Nursing: Critical Thinking for Collaborative Care (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, p. 38.

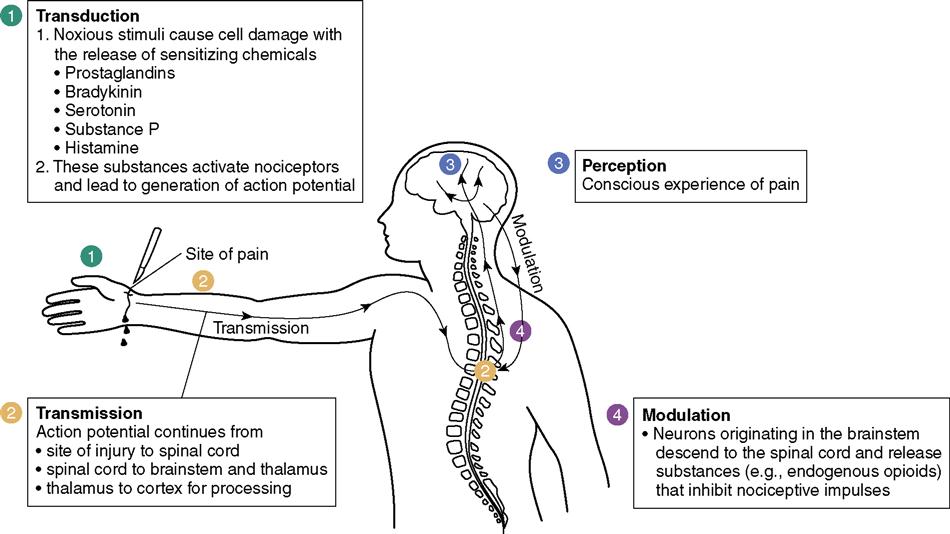

Four phases of pain are associated with nociceptive pain (Figure 7-2) (Lewis et al., 2011):

2. Transmission involves movement of the pain sensation to the spinal cord.

3. Perception occurs when impulses reach the brain and the pain is recognized.

Aspects of nociceptive pain relate to nursing practice in several ways:

Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain is associated with a dysfunction of the nervous system that involves an abnormality in the processing of sensations. These dysfunctions in the nervous system are often associated with medical conditions rather than with tissue damage. The dysfunction may occur in the peripheral or central nervous system. In peripheral nervous system neuropathic pain, it is believed that pain receptors become sensitive to stimuli and send pain signals more easily. Nerve endings grow additional branches that send stronger pain signals to the brain. As the branches grow, they influence touch and warmth receptors. Other peripheral nervous system conditions may cause neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain may be the result of damage to nerve roots such as compression or entrapment. Another dysfunction of the central nervous system occurs when the pain signal that would normally move from the periphery toward the brain reverses and the signal is sent in the opposite direction. Phantom pain, the pain felt in a limb after amputation, is an example.

Aspects of neuropathic pain relate to nursing practice in several ways:

Perception of Pain

Pain is a subjective experience. Only the patient knows the location of the pain, its degree of intensity, and which treatment regimen works and how long it is effective. Reactions to pain can vary widely from person to person and in the same individual under different circumstances.

Pain threshold is the point at which pain is perceived. Relaxation and distraction strategies can alter the perception of pain. Pain tolerance is the length of time or the intensity of pain a person will endure before outwardly responding to it. Tolerance varies among people and is influenced by culture, pain experience, expectations, and role behaviors. People with acute pain (of recent onset, lasting less than 6 months) may have physiologic symptoms such as increased pulse and respiratory rates, increased blood pressure, diaphoresis, and increased muscle tension. They may also experience nausea and vomiting. People with chronic pain (lasting months or years) may have learned adaptive methods that allow them to have some control over their pain. Symptoms associated with chronic pain include irritability, depression, withdrawal, and insomnia. Coping with any pain takes a lot of energy, and patients who are debilitated are less able to withstand pain than are strong, robust people. Fatigue caused by pain can lead to an increase in pain perception.

Pain can cause a variety of physiologic responses, including increased respiratory rate, pulse, or blood pressure; muscle tension; sweating; flushing or pallor; and frowning or grimacing. Although the presence of any of these factors may indicate pain, their absence does not prove the absence of pain.

A person’s cultural background influences feelings about pain. In much of Western culture it is considered valuable to have a high pain tolerance, particularly among men. Other cultures promote the idea that to endure pain is natural, or honorable. A nurse whose cultural background approves the “stiff upper lip” approach to handling pain may see the patient who outwardly expresses pain as weak or manipulative. By contrast, those patients whose cultural upbringing causes them to hide and deny pain may suffer needlessly unless the nurse can intervene and help them to understand that analgesia will aid the healing process by encouraging movement and decreasing fatigue. Learning to accept without judgment the various ways of coping with and expressing pain is a very necessary process for nurses.

Acute versus Chronic Pain

Acute Pain

Patients with acute pain frequently experience fear and anxiety, which can take many forms. They may fear that something is seriously wrong, that they will never get relief from the pain, or that they will become addicted to the pain medication. The anxiety and fear of these patients frequently are alleviated by first providing adequate analgesia to relieve the pain and then educating them about their pain and the methods that can be used to control pain safely. Including patients in planning care reassures patients that health care professionals believe them and want to help.

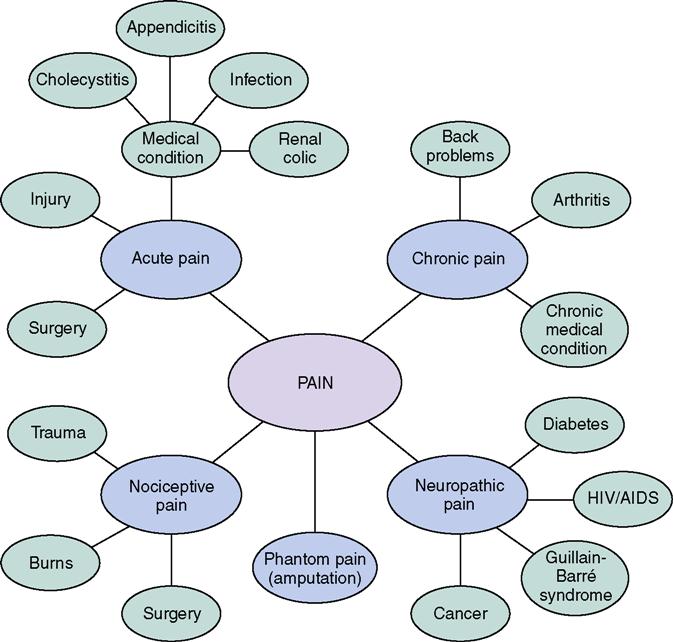

Rely on the patient’s report of pain and intervene to promote comfort. Table 7-2 compares acute and chronic pain. Some nurses hesitate to administer pain medication to patients with a history of drug abuse. Such patients may experience acute pain, for example, following surgery. The postoperative period is not the time to withhold pain medication from any patient. Concept Map 7-1 shows the various types and causes of pain.

Table 7-2

| Acute | Chronic | |

| Duration | Hours to days. | Months to years. |

| Prognosis for relief | Good; may resolve spontaneously or in response to analgesic therapy. | Poor unless complicating factors removed; spontaneous relief unusual. |

| Cause | Relatively easy to identify. | Sometimes cause is known, but diagnosis may be complex or undetermined. |

| Psychosocial effects | Usually transient or none. May temporarily disrupt normal activities or routine. | Can affect ability to earn a living, enjoy social activities, maintain self-esteem. |

| Effect of therapy | Medication usually beneficial, surgery often helpful. | Medications may be helpful, but patient may become dependent. Multiple medication regimen may be used. Surgery may help, but also may worsen the problem. |

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is commonly associated with depression. People who hurt most or all of the time frequently resign themselves to the idea that they can never again live a normal life. Research and the work of several outstanding pain centers and nurse and physician specialists now offer new pain relief techniques for sufferers of chronic pain. Many people whose lives were previously dictated by their pain now experience good control and have returned to normal, productive lives.

Nursing Management

Assessment (Data Collection)

Because no technology can accurately and objectively measure pain, you must use a combination of evaluation methods, including observation and rating scales.

Observation

Appearance

The patient’s face may look tense, drawn, or pale. There may be a grimace or even a look of fear.

Behavior

A normally verbal patient may become quiet or withdrawn. One who is normally pleasant may become irritable, demanding, or argumentative. The individual may protect or “cradle” the painful area with the hands or arms. Tears, refusal of food or drink, or any behavior that is out of the ordinary for the individual may be an indication of pain.

Activity Level

A person in pain often reduces activity to a minimum. Staying in bed, creeping slowly from place to place, stooping over during ambulation, and stopping frequently to rest or lean against a support can all indicate pain.

Verbalization

Many individuals in pain may verbalize their discomfort, but it is not always easy to interpret the degree of pain from what is said. Limited vocabulary, lack of experience in verbalizing abstract concepts, fear of disbelief or disapproval, cultural stoicism, and fear of becoming addicted to the analgesic all can impair the person’s ability to communicate the degree of pain.

Physiologic Clues

Physiologic clues to pain include rapid, shallow, or guarded respirations, pallor, diaphoresis, increased pulse, elevated blood pressure, dilated pupils, and tenseness of the skeletal muscles. However, remember that problems other than pain can also cause these physiologic clues to occur. All physiologic changes must be fully assessed to determine the cause.

Pain Rating Scales

Several rating scales have been developed for use in pain evaluation. When using a pain rating scale, it is important that the nursing staff use it consistently and that the patient fully understands how to use it. The type of scale being used and any pertinent information about how the patient uses the scale must be included in the patient care plan.

When using a pain rating scale, it is important that the nursing staff use it consistently and that the patient fully understands how to use it. The type of scale being used and any pertinent information about how the patient uses the scale must be included in the patient care plan.

Numbered Scale

Numbered scales ask the patient to rate the degree of pain as a number from 0 to 5 or 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain and the highest number indicating the greatest amount of pain imaginable. The numbers in between show graduated levels of pain. The scale may be simply verbal, or it may actually be drawn on a piece of paper so the person can mark or point to the degree of pain. Number scales can be used very effectively with people who have a good understanding of the numerical concept and who like a strictly logical approach. They are not appropriate for young children, anyone who has difficulty with numbers, or anyone who is confused or disoriented.

Visual Scale

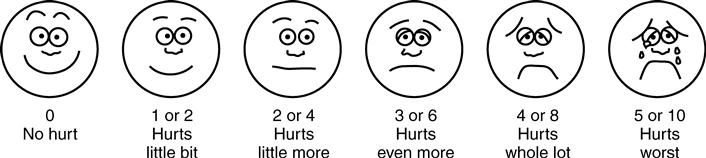

Some visual scales use photographs or simple drawings of faces with expressions showing a pain-free state (happy and smiling) that progress through a series of faces showing increased discomfort. The final picture shows a face either crying or with an intense grimace (Figure 7-3).

or simple drawings of faces with expressions showing a pain-free state (happy and smiling) that progress through a series of faces showing increased discomfort. The final picture shows a face either crying or with an intense grimace (Figure 7-3).

Color Scale

A color scale allows the patient to select colors that represent varying degrees of pain. Colored pieces of paper or plastic (e.g., poker chips), crayons, or markers can be used. The patient selects a color that represents no pain, a color that represents severe pain, and then one, two, or three other colors for pain levels in between. This scale is often used with children, but very young children cannot understand more than three or four possible choices.

Pieces of Pain Scale

This scale uses five poker chips or other identical, plain objects that represent “pieces” of pain. The patient indicates the degree of pain by selecting the number of chips that equals the intensity of pain being experienced.

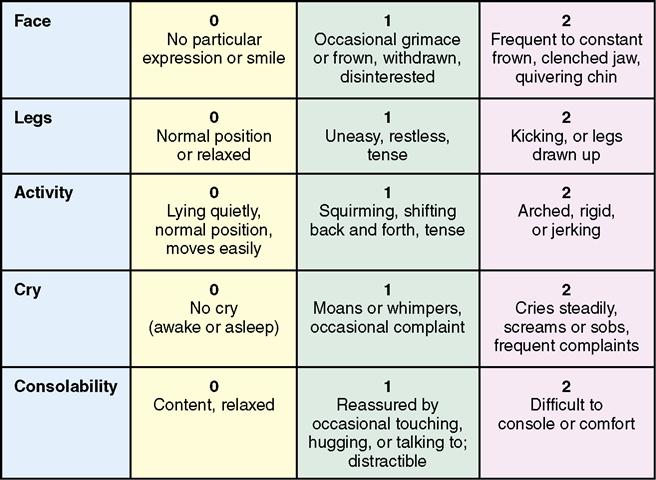

Behavioral Pain (FLACC) Scale

This scale is used with patients who are cognitively impaired or cannot speak. The nurse assesses the patient’s behavior in categories such as facial expression, limb movement, and activity level (Figure 7-4). A score from 0 to 2 is obtained for each category, and the category scores are added together to arrive at a pain score total of 0 to 10. It is useful when assessing the pain of confused or nonverbal adults, infants, and young children.

Data Collection Difficulties

Much of the data gathered when assessing a patient’s pain comes from conversation with the patient, which presents a variety of problems. The first problem is language itself. Concepts of the true meaning of words in a common language may vary greatly from person to person. It is important to discuss the common words used to describe pain and to agree on their meaning (Table 7-3). It also is important that documentation include the patient’s exact words.

Table 7-3

Common Terms to Help Patients Describe Pain

| Degree of pain (from least to most severe) | Absent, minimal, mild, moderate, fairly severe, severe, very or extremely severe, excruciating |

| Quality of pain | Crushing, tingling, itching, throbbing, pulsating, twisting, pulling, burning, searing, stabbing, tearing, biting, blinding, nauseating, debilitating |

| Frequency of pain | Constant, intermittent, occasional, related to something specific (e.g., only when coughs) |

The need to work through an interpreter or to deal with language difficulties when the patient speaks a foreign language compounds the problem of communicating pain. Whenever possible, the nurse should use a medical professional (rather than a family member) with a good knowledge of both languages as an interpreter. Most hospitals have a list of approved interpreters to assist in these situations. Patients may hide personal, embarrassing, or painful information if the interpreter is a family member or personal friend.

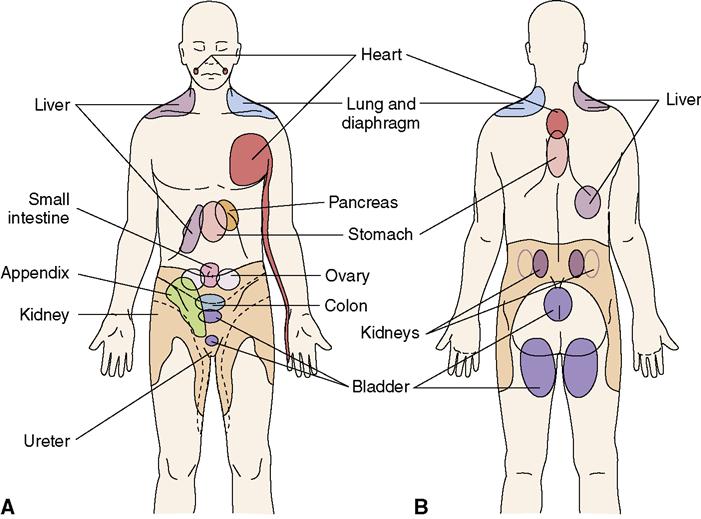

Describing the location of pain can be made difficult by the problem of referred pain (pain felt in a different part of the body from where it actually originates) (Figure 7-5). Heart pain may be felt in the jaw or radiating down the arm. Gastric pain may center in the area of the heart rather than the stomach. There also is a tendency not to believe an individual’s statement of pain if there is no outward appearance of pain. For example, a patient watching

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Elder Care Points

Elder Care Points