Section 6. Respiratory, renal and gastrointestinal systems

6.1. Respiratory system

Cough mixtures and decongestants

A cough is a symptom and the underlying cause should be found where necessary. The cough mixture will only treat the cough and not the cause.

If the cough is dry and unproductive, a cough suppressant may be given. These are useful if sleep is disturbed but can cause retention of sputum in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) where they should not be used.

▪ Opiates are powerful cough suppressants.

▪ Codeine phosphate is most commonly used and is available as codeine linctus or as pholcodine. It is constipating and may cause dependence if given over a period of time. Large doses may also cause some respiratory depression.

▪ Morphine is used in palliative care as a cough suppressant in terminal lung cancer. Methadone linctus is an alternative but may accumulate due to its long duration of action. These drugs are not used for other forms of cough as they cause opioid dependence in addition to sputum retention.

▪ Cough suppressants sold over the counter (OTC) usually contain sedating antihistamines such as diphenhydramine as the cough suppressant and their main action is to cause drowsiness.

▪ Simple linctus is a cheap and safe preparation that may sooth a dry and irritating cough. It contains citric acid and is safe to give in paediatric form to children.

Expectorants are taken to aid the expulsion of secretions when coughing. There is no real evidence that they can actually do this.

▪ Ammonia and ipecacuanha mixture would cause vomiting in larger doses but in a small dose is taken as an expectorant. It has to be recently prepared.

Mucolytics are given to decrease the viscosity of the sputum and so enable it to be expectorated. They are helpful in some patients with COPD.

▪ Carbocisteine and mecysteine hydrochloride are used but should not be given to people with peptic ulcer as they interfere with the mucosal barrier in the stomach.

▪ Dornase alpha is an enzyme that breaks up DNA in the sputum in cystic fibrosis, thus reducing viscosity and aiding clearance of secretions. It is produced by genetic engineering and administered by inhalation of a nebulised solution.

Nasal decongestants may be given orally for systemic action to prevent the rebound congestion that can occur following nasal administration.

▪ They contain pseudoephedrine and are stimulants of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) so should be used with caution in a list of conditions including hypertension (see the British National Formulary (BNF) for detail). They should not be given to patients taking monoamine oxidase antidepressants (see section 4.5).

▪ Available preparations include Sudafed® and Galpseud®. Many OTC preparations also contain pseudoephedrine.

Aromatic inhalations of volatile substances such as menthol and eucalyptus may be taken to relieve nasal congestion or in sinusitis. Tincture of benzoin (Friars’ balsam) is also occasionally used. These substances are added to hot, not boiling, water and the vapour is inhaled. Great care must be taken not to scald the person.

Pulmonary surfactants

These are used in neonates to prevent respiratory distress syndrome. The immature lungs in a preterm baby cannot manufacture their own surfactant. This is needed to reduce surface tension in the alveoli and prevent the lung collapsing following expiration. Available are beractant ( Survanta®) and proactant alfa ( Curosurf®), both given via the endotracheal tube in specialised neonatal units.

Respiratory disorders

May be divided into:

▪ obstructive – causing narrowing of the airways such as in asthma and bronchitis

▪ restrictive – where the actual volume available in the lungs for gas exchange is reduced as in pulmonary fibrosis.

Asthma and chronic bronchitis are the two main obstructive disorders affecting the respiratory tract.

The effect of the autonomic nervous system on the airways

▪ The airways are constricted by acetylcholine, the transmitter of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). They are relaxed by circulating adrenaline (epinephrine).

▪ Mucus secretion is inhibited by the SNS and stimulated by the PNS as well as chemical mediators and cold air.

▪ Drugs that inhibit the action of acetylcholine will relax the airways and reduce mucus secretion. One such drug is ipratropium ( Atrovent®) which is a cholinergic antagonist.

▪ Bronchodilators such as salbutamol and ipratropium are needed to relax the smooth muscle of the airways when bronchoconstriction is present.

Asthma

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory respiratory disorder that varies in severity from mild to fatal. Initially it is a reversible condition caused by bronchospasm, increased secretion of sticky mucus and oedema.

Symptoms include a cough, wheeze, chest tightness, difficulty with expiration and shortness of breath. These symptoms tend to be:

▪ variable

▪ intermittent

▪ worse at night

▪ provoked by triggers including exercise.

Asthma has three characteristics:

▪ Airflow limitation usually reversible with treatment.

▪ Airway hyper-responsiveness.

▪ Inflammation of the bronchi with oedema, smooth muscle hypertrophy, mucus plugging and epithelial damage.

As a result of the inflammation the airways are hyper-reactive and narrow easily in response to a wide range of stimuli.

While initially reversible, the inflammation may lead to an irreversible obstruction of airflow. If the bronchospasm is frequent and prolonged, the bronchial muscle layer may become permanently thickened which results in long-term bronchoconstriction.

During exacerbations the patient will have reduced peak flow rates and usually a wheeze. Outside acute episodes there may be no objective signs of asthma.

In extrinsic asthma there is a definite external cause. It commonly develops during childhood, often runs in families, and identifiable factors provoke wheezing. It is a hypersensitivity disorder and may be associated with hay fever and eczema that also occur in individuals who are atopic (have a high incidence of allergies due to increased levels of IgE antidodies in their blood).

Precipitating factors may include house dust mites, pollens and spores, pets, smoke, chemicals, certain foods and drugs (especially beta blockers and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen). In some, an asthma attack is brought on by exercise or even just cold air. Emotional factors may also be involved.

In intrinsic asthma no causative agent can be identified. This type of asthma begins in adult life and airflow obstruction is more persistent. Most exacerbations have no obvious stimuli other than a respiratory tract infection.

Response to an allergen usually begins within minutes (early reaction), reaches its maximum in about 15–20 minutes and subsides within an hour.

Following the immediate reaction, many, but not all, develop a more prolonged and sustained attack that is more resistant to drug therapy.

Acute severe asthma

The patient may be very anxious and a calm atmosphere is essential. It should be noted that speed of onset varies – some attacks come on over minutes, in some deterioration occurs slowly over days.

Asthma can produce symptoms of all grades varying from very mild to life-threatening. Its danger should never be underestimated and several hundred people die each year from asthma.

Asthma can produce symptoms of all grades varying from very mild to life-threatening. Its danger should never be underestimated and several hundred people die each year from asthma.Life-threatening asthma

▪ PEF <33% of best or predicted best (approx. 150 l/min in adults).

▪ Saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO 2) <92%.

▪ A silent chest, cyanosis or feeble respiratory effort.

▪ Bradycardia or hypotension.

▪ Exhaustion, confusion or coma.

Patients are not always distressed and may not show all these features – any one of the features is sufficient.

Patients are not always distressed and may not show all these features – any one of the features is sufficient.If the patient deteriorates despite pharmacological interventions it may be necessary to use intermittent positive-pressure ventilation.

Medication in asthma

The British Thoracic Society (BTS) has published revised guidelines in 2007 – the British Guidelines on the Management of Asthma.

These recommend a stepwise treatment but do emphasise that treatment can begin at any step on the ladder (Table 6.1). If that step does not control the asthma, the treatment moves up to the next step.

| *Beclometasone diproprionate or equivalent |

| Patients should start treatment at the step most appropriate to the initial severity of their asthma. Check concordance and reconsider diagnosis if response to treatment is unexpectedly poor. Move up the steps to improve control as needed. Move down to find and maintain lowest controlling step. |

| Step 1 – mild, intermittent asthma |

| Inhaled short-acting β 2 agonist as required |

| Step 2 – regular preventer therapy |

| Add inhaled steroid 200–800 mcg/day* |

| 400 mcg is an appropriate starting dose for many patients |

| Start at dose of inhaled steroid appropriate to severity of disease |

| Step 3 – initial add-on therapy 1 Add inhaled long-acting β 2 agonist (LABA) 2 Assess control of asthma • good response to LABA – continue LABA • benefit from LABA but control still inadequate – continue LABA and increase inhaled steroid dose to 800 mcg/day* (if not already on this dose) • no response to LABA – stop LABA and increase inhaled steroid to 800 mcg/day. * If control still inadequate, institute trial of other therapies, leukotriene receptor antagonist or SR theophylline |

| Step 4 – persistent poor control |

| Consider trials of: • increasing inhaled steroid up to 2000 mcg/day* • addition of a fourth drug e.g. leukotriene receptor antagonist, SR theophylline, β 2 agonist tablet |

| Step 5 – continuous or frequent use of oral steroids |

| Use daily steroid tablet in lowest dose to provide control |

| Maintain high-dose inhaled steroid at 2000 mcg/day* |

| Consider other treatments to minimise the use of steroid tablets |

| Refer patient for specialist care |

The aim is to totally control symptoms and reduce medication to a level that will maintain this control.

Drugs are usually delivered directly into the lungs by inhalation.

Two major types of medication are used:

▪ Relievers – bronchdilators e.g. salbutamol.

▪ Controllers – anti-inflammatory steroids.

Drugs used in bronchoconstriction – bronchodilators

Bronchodilators give relatively rapid relief of symptoms and are believed to work predominantly by relaxation of airway smooth muscle.

▪ Xanthines e.g. theophylline.

▪ Muscarinic receptor antagonists e.g. ipratropium bromide ( Atrovent®).

β 2 Agonists

These are physiological antagonists of smooth muscle contraction and so they can relax the smooth muscle of the respiratory tract whatever the cause of the bronchoconstriction.

▪ Short acting – salbutamol, terbutaline.

▪ Longer acting – salmeterol, eformotorol.

Short-acting β 2 agonists

Most frequently used is salbutamol. It causes dilation of the bronchioles and thus helps breathing. Will also relax uterine muscle and may be used to delay the onset of premature labour (see section 7.5).

Salbutamol has a direct action on the β 2 adrenergic receptor that:

▪ relaxes the smooth muscle

▪ inhibits mediator release from mast cells

▪ may inhibit vagal tone and increase mucus clearance by an action on the cilia

▪ has no effect on chronic inflammation.

Salbutamol is the drug of choice in an emergency as well as in mild asthma, where it is given as needed.

▪ Does not reduce the underlying inflammation in the respiratory tract. If asthma worsens the patient should not rely on this drug but needs additional steroid therapy.

▪ Has a rapid onset of action and starts to work within minutes. Its maximum effect is within 30 minutes and its duration of action is up to 4–6 hours.

Salbutamol is usually given by inhalation. This enhances selectivity by increasing concentration in the airways and reduces the chances of systemic side effects.

The inhalation may be in the form of a metered dose inhaler (MDI) or a dry powder device.

▪ 20% of the inhaled dose may be absorbed into the body. Only 10–25% actually stays in the lungs – the rest is swallowed.

▪ The inhaler may be taken prior to an activity or stimulus that is likely to cause bronchoconstriction. Many patients can prevent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction if they inhale a short-acting β 2 stimulant 5–10 minutes before exercise starts.

▪ In a severe asthma attack the client will need higher doses of β 2 stimulant which is given in the form of a nebuliser.

Salbutamol is also available orally in the form of a syrup or tablets. A solution for intramuscular or intravenous administration is available.

Side effects

▪ Tachycardia – reflex effect from increased peripheral vasodilation via β 2 receptor.

▪ In high doses it also causes a muscle tremor – commoner in older patients.

▪ Reduces the potassium level in the blood and may cause hypokalaemia – especially if xanthines and steroids are given as well.

β 2 stimulants do not control the inflammation in asthma.

β 2 stimulants do not control the inflammation in asthma.▪ Some evidence that tolerance to salbutamol can develop in asthma as with intense prolonged use there may be a decline in the numbers of β 2 receptors in the lungs.

▪ Steroids can help here because they inhibit beta receptor down-regulation.

▪ Patients with mild or moderate chronic asthma should take shorter-acting β 2 stimulants as needed to relieve symptoms. Regular fixed-interval use gives no additional benefit and may possibly cause harm.

If given to asthmatic patients, β 2 antagonists such as propranolol can precipitate a potentially serious asthma attack. This is because the bronchodilation normally occurring in response to stimulation of the β 2 receptor cannot occur if it is blocked.

If given to asthmatic patients, β 2 antagonists such as propranolol can precipitate a potentially serious asthma attack. This is because the bronchodilation normally occurring in response to stimulation of the β 2 receptor cannot occur if it is blocked.Long-acting β 2 agonists e.g.salmeterol, formoterol

The longer-acting β 2 stimulants are not used in the immediate management of acute symptoms as they take time to work. They are designed for regular twice-daily administration and not for use prior to activities.

A single dose gives bronchodilation lasting 8–12 hours.

Used in asthma but only when the patient is already on inhaled corticosteroids.

Salmeterol and fluticasone (a steroid) are available in one inhaler ( Seretide®).

Muscarinic receptor antagonists (anticholinergics)

Ipratropium bromide (Atrovent®)

Related to atropine and relaxes bronchial constriction caused by increased tone due to parasympathetic stimulation. This occurs in asthma produced by irritant stimuli and can occur in allergic asthma.

▪ Can provide short-term relief in asthma but salbutamol acts more quickly.

▪ Effective in COPD.

▪ Inhibits mucus secretion and may increase mucociliary clearance of bronchial secretions.

▪ Has no effect on the later inflammatory stages of asthma.

▪ Given as an inhaled dose in an aerosol or nebuliser and is not absorbed from the gut.

▪ Maximum effect 30–60 minutes after inhalation and lasts about 3–6 hours.

▪ It has few unwanted effects and in general is safe and well tolerated.

▪ It can be given with β 2 agonists.

Side effects

These are due to the antimuscarinic effects.

▪ Dry mouth.

▪ Nausea, constipation.

▪ Headache.

▪ Tachycardia and occasionally atrial fibrillation.

Can cause worsening of glaucoma (dilate the pupil) and may cause retention of urine in prostatic hypertrophy.

Xanthines

Naturally occurring xanthines include theophyllineand caffeine. Theophylline and caffeine are contents of tea and coffee.

Xanthines are bronchodilators but the use of theophylline has declined due to the great effectiveness of β 2 agonists.Theophylline has many more side effects and a lower safety profile than salbutamol. It is necessary to monitor the levels of theophylline in the plasma as the drug has a narrow margin between the therapeutic and the toxic dose. 10–20 mg/l are usually needed for bronchodilation but adverse effects may occur even in this range. As the concentration increases so does the severity of the toxicity.

Plasma theophylline concentrations are increased in heart failure, liver disease and in the elderly. Concentrations are decreased in smokers and chronic drinkers.

Plasma theophylline concentrations are increased in heart failure, liver disease and in the elderly. Concentrations are decreased in smokers and chronic drinkers.Modified-release tablets of theophylline are available as Slo-Phyllin®, Uniphyllin Continus® or Nuelin SA®.

Theophylline, as aminophylline(theophylline mixed with ethylenediamine to give greater water solubility), is occasionally given by very slow intravenous injection (over 20 minutes) or in dextrose 5% as an infusion for severe asthma.

Modified-release tablets of aminophylline are available as Phylocontin Continus®. Usually given at night in COPD or to prevent nocturnal attacks of asthma. Phylocontin Continus Forte® tablets are available for smokers or those with increased metabolism of theophylline.

Mechanism of action

▪ Inhibits the enzyme phosphodiesterase and so prevents the breakdown of cyclic AMP. Produce direct smooth muscle relaxation.

▪ Does have some anti-inflammatory action as well.

▪ Relatively high doses are needed for airway smooth muscle relaxation but there is increasing evidence that theophylline has anti-inflammatory properties or immonomodulatory effects at lower plasma concentrations (5–10 mg/litre).

Other actions and side effects

▪ Actions on CNS. Have a stimulant action causing increased alertness. Can cause tremor and nervousness and interfere with sleep.

▪ Actions on the cardiovascular system. All xanthines stimulate the heart. Have positive inotropic and chronotropic action. Cause vasodilation in most blood vessels but vasoconstriction in the cerebral blood vessels.

▪ Actions on the kidney. Have a weak diuretic effect.

▪ Increase adrenaline (epinephrine) secretion.

▪ Inhibit prostaglandins.

▪ Side effects include nausea, vomiting, nervousness, tremor, headache, restlessness, gastro-oesophageal reflux.

▪ In greater concentrations arrhythmias may occur that can be fatal.

▪ Epileptic seizures, especially in children (usually plasma concentration >3 mg/l).

Caffeine is very similar to aminophylline and is a mild central stimulant. It is not used therapeutically in adults.

Histamine antagonists

Although mast cells are thought to play a part in the immediate phase of allergic asthma, histamine antagonists have been disappointing in the treatment of asthma. Some of the newer, nonsedating antihistamines such as cetirizine have been shown to be effective in mild atopic asthma such as that due to pollen allergy.

Preventer therapy in asthma

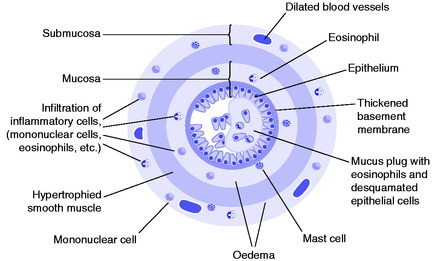

It is important to prevent chronic inflammation of the airways and airway remodelling from occurring in asthma. These changes are due to the release of chemical mediators such as leukotrienes, prostaglandins and bradykinin produced by inflammatory cells including eosinophils (a type of white blood cell). Histamine produces immediate bronchoconstriction, whereas leukotrienes act more slowly. They attract large white blood cells called macrophages to the area and these release more chemicals that can be damaging to the lining of the airways, causing loss of epithelial cells and increased hyper-reactivity. Growth factors are released that cause thickening of the basement membrane and the smooth muscle layer in the bronchioles. These changes are shown in Figure 6.1.

|

| Fig. 6.1 Schematic diagram of a cross-section of a bronchiole showing the changes that can occur with severe chronic asthma. The individual elements depicted are not of course drawn to scale. Reproduced with permission from Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology, 6th edition, by H P Rang, M M Dale, J M Ritter et al, 2007, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh. |

Steroids in asthma

The most effective drugs to prevent inflammatory changes in adults and older children are inhaled steroids. They are given by inhalation to prevent asthma attacks and were introduced in the 1970s. Their use is increasing in younger children and infants as evidence of their safety increases. All patients with regular, persisting symptoms of asthma need treatment with inhaled steroids. They reduce the inflammatory swelling of the airways and decrease the number of asthma attacks, preventing airway remodelling.

Mechanism of action

▪ Bind to glucocorticoid receptors in the cytoplasm that regulate the expression of multiple genes.

▪ Inhibit the generation of chemicals by white blood cells, particularly the leukotriene IL-5. This reduces the recruitment of inflammatory cells such as eosinophils.

▪ Inhibit other leukotrienes including the spasmogens LTC 4 and LTD 4 as well as the prostaglandins PGE 2 and PGI 2.

▪ Long-term use eventually reduces the early phase response to allergens and prevents exercise- induced asthma. This may be because they reduce the synthesis of the cytokine that regulates mast cell production.

▪ They inhibit the downregulation of the beta receptor and so prevent tolerance to β 2 agonists. Salmeterol should not be prescribed unless the patient is already receiving a steroid by inhalation.

▪ They do have side effects over a period of time and are given in an inhaled form to prevent systemic action as much as possible.

▪ Reduce airway hyper-responsiveness. Improvement occurs slowly over several months.

▪ They suppress inflammation but do not cure underlying cause.

Administration

The exact threshold for the introduction of steroids is still open to debate but the asthma guidelines say they should be considered if the patient has had exacerbations of asthma in the last 2 years or the salbutamol inhaler is being used more than twice a week or the patient has asthma symptoms three times a week or is waking one night a week.

Five inhaled corticosteroids are licensed for the treatment of patients with asthma. These are beclometasone dipropionate (BDP) ( Becotide®),budesonide ( Pulmicort®), fluticasone propionate (FP) ( Flixotide®), mometasone furoate ( Asmanex®) and ciclesonide ( Alvesco®).

Each is available for administration via a metered dose inhaler (MDI), with or without a spacer, or as a dry powder from a range of different devices.

The starting dose is usually 400 mcg of BDP daily in an adult, and when control of the asthma has been established, this is titrated to the lowest dose needed to control the symptoms. The reader is referred to the BNF and asthma guidelines for the doses of different inhaled steroids and their equivalency.

Most inhaled steroids are more effective if taken twice daily, except ciclesonide which is once daily. When control is good, once-daily steroids may be given, at the same time of day.

Side effects

These are less than occur with the systemic use of steroids but are a major issue in the long-term use of inhaled steroids. They are mainly related to the size of the inhaled dose but some people do appear more susceptible. High doses of inhaled steroid should only be used when smaller doses are less effective and the large dose is clearly beneficial.

Local side effects

▪ Due to deposition of inhaled steroid in the oropharynx.

▪ Candida infections of the mouth may occur in about 5% of patients (thrush). This is due to local lowering of resistance by the steroid and a spacer helps to prevent this. It can be treated by antifungal lozenges without discontinuing the steroid inhaler.

▪ Hoarseness (dysphonia) develops in up to 40% of patients taking high doses.

▪ Throat irritation and cough may be due to additives in the MDI – rarely with dry powder inhalers. The salbutamol inhaler should be taken first to prevent this.

Systemic side effects

These are due to absorption both from the respiratory tract and the gastrointestinal tract. Absorption from the gastrointestinal tract is greatly reduced by the use of a spacer and mouthwashes.

▪ Adrenal suppression can occur with high doses over a prolonged period and a steroid card should be carried. Patients may need corticosteroid cover when having an operation or at other times of stress. Excessive doses should be avoided in children where adrenal crisis and coma have been seen.

▪ Reduced bone density and osteoporosis can occur with high doses over a long period.

▪ Growth should be monitored in children as slowing may occur. With normal doses this does not appear to affect the growth achieved in adulthood.

▪ Small risks of cataract and glaucoma have been reported.

Oral steroids

▪ A severe acute asthma attack is treated with a short course of oral steroids. Prednisolone is given in a high dose (e.g. 40–50 mg daily) for a few days only. It can usually be stopped abruptly but should be tailed off if asthma control is poor.

▪ Regular oral steroids (at the lowest possible dose) are only indicated in the most severe asthmatic patients who cannot be controlled with high-dose inhaled steroids and additional bronchodilators. The inhaled steroid is continued to allow the smallest dose of oral steroid to be given.

▪ The oral steroid should be given once daily in the morning as this upsets the body’s own rhythm of secretion less.

▪ Enteric-coated tablets cause less gastrointestinal disturbance.

Parenteral steroids

Hydrocortisone is sometimes given intravenously in a severe asthma attack.

Cromates

Sodium cromoglicate (Intal®), nedocromil sodium (Tilade®)

▪ Little used now but are alternatives if steroids cannot be used.

▪ Of benefit in some adults but more effective in children aged 5–12 years.

▪ Need to be given regularly and do reduce both immediate and late-phase asthmatic responses, reducing bronchial hyper-responsiveness in some cases of allergic asthma.

▪ Action is not totally understood but stabilises the mast cell and prevents release of histamine.

▪ Very poorly absorbed orally and given by pressurised aerosol or rotahaler.

▪ The usual dose is three to four inhalations daily.

▪ Bitter taste – now available in menthol aerosols to mask the taste.

▪ Burning sensation due to activation of thermoreceptors.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

Montelukast (Singulair®) and zafirlukast (Accolate®)

The cysteinyl leukotrienes LTC 4, LTD 4 and LTE 4 are important chemical mediators in asthma. They are released by eosinophils, basophils and mast cells. Activation of leukotriene receptors results in contraction and proliferation of smooth muscle, oedema, eosinophil migration and damage to the mucous layer in the lung.

Side effects

Include gastrointestinal symptoms and headaches.

Some have developed abnormalities in liver function – need to check regularly.

Treatment does not allow a reduction in existing corticosteroid treatment.

Omalizumab

This is a monoclonal antibody that binds to IgE. It is licensed as an add-on in those who have proven IgE-mediated sensitivity to inhaled allergens when asthma cannot be controlled by the use of other drugs. It is only prescribed as prophylaxis by asthma specialists.

Inhalers and nebulisers

Inhalation is the preferred route for drugs aimed at the respiratory tract. The drug is administered directly to the bronchioles, therefore smaller doses are required. Compared to oral administration there should be more rapid relief with fewer side effects.

Inhalation devices

Inhalation devices include pressurised MDIs, breath-actuated inhalers and dry powder inhalers.

▪ The choice of device is vitally important as incorrect use leads to suboptimal treatment.

▪ The choice is dependent upon several different factors including the severity of the disease, the patient’s age, co-ordination of movement and manual dexterity.

▪ Patient preference is also important.

▪ Many can be taught to use pressurised MDIs but there are groups such as the very young and the elderly who find this difficult.

▪ Spacer devices help here as there is no need to co-ordinate actuation with inhalation. Spacers are effective even in children under 5 years.

▪ Alternatives are breath-actuated inhalers or dry powder inhalers. These are activated by the patient’s inhalation and eliminate the need for correct co-ordination. They may cause coughing and are less suitable in children.

▪ There is an optimum peak inspiratory flow (PIF) for any inhaler device. The MDI uses a propellant, and to get the best lung deposition, inhalation should be slow. In comparison, dry powder inhalers work better when inhalation is faster.

MDIs

▪ Most commonly used type of inhaler.

▪ Suspension of the active drug with particle size of 2–5μm, in a liquefied propellant.

▪ The inhaler releases the drug in a droplet size of 35–45μm. The propellant (responsible for the increased particle size) evaporates on expulsion from the inhaler.

▪ Older inhalers were chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) propellants and damaged the ozone layer. These have changed to hydrofluoroalkanes which do not cause this damage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access