CHAPTER 6. Principles of Forensic Evidence Collection and Preservation

Richard Saferstein

Forensic science begins at the crime scene. If evidence cannot be recognized, retrieved, and preserved at the scene, little can be done at the forensic laboratory to salvage the situation. The healthcare professional is in a unique position to facilitate evidence collection. In some situations, the healthcare professional will be in the presence of police personnel at critical moments during the collection and preservation of physical evidence. At other times, the healthcare technician may be the sole determiner of what evidence to collect. The permutations of crime are so varied that one cannot reduce to simple sentences or paragraphs scenarios depicting when the heathcare professional will need to step forward to make critical decisions on evidence preservation. Well-written chapters in this volume already amply depict the basics of crime-scene investigation and the role of DNA profiling in criminal investigation. There is no need to duplicate these efforts. What follows is a short primer on the collection and preservation of key items of physical evidence.

Evidence Sources and the Environment

The conditions under which forensic evidence is gathered are not always ideal, and it may be that the first opportunity to collect evidence will take place in a hospital environment. For this reason, it is imperative that physicians and nurses present in emergency room situations be knowledgeable in recognizing and preserving relevant forensic evidence. This discussion is not designed to mold the healthcare technician into an evidence collector. It is written with the objective of sensitizing the healthcare professional to physical evidence and to an appreciation of how one optimizes the role that science plays in criminal investigation.

The patient’s body, hospital supplies and equipment, medical documentation, and the healthcare environment itself can be important sources of evidence in a criminal investigation. Nurses should be prepared to identify, protect, collect, preserve, and transmit certain items of evidentiary value.

Locard’s principle

When a person or object comes in contact with another person or object, there exists a possibility that an exchange of materials will take place. This is referred to as Locard’s principle. This exchange can prove useful when investigating the circumstances surrounding a crime or an accident. The presence or absence of physical evidence can corroborate or disprove a person’s recollection of events. Physical evidence can implicate a person to the commission of a crime, or it can exonerate those wrongly suspected or accused of committing a crime. Physical evidence is an invaluable tool that law enforcement authorities utilize for the reconstruction of the circumstances surrounding the incident. However, evidence is only of value in an investigation or in a court of law if its integrity is upheld through careful handling, proper collection, and a documented chain of custody.

Chain of custody

Chain-of-custody documents record the link formed between each person who handles a piece of evidence. Transferring evidence from one person or one location to another must be accompanied with written documentation. The end result is a paper trail that records where the evidence was, on what date, and who held responsibility for it from the time it was collected until the time it is presented in court. It is best to use chain-of-custody forms designated by the organization for whom one works. This form should provide a clear and concise presentation for any exchanges of the physical evidence. Once an evidence container is selected, whether it is a box, bag, vial, or can, it also must be marked for identification. A minimum record would show the collector’s initials, location of the evidence, and date of collection. If the evidence is turned over to another individual for care or delivery to the laboratory, this transfer must be recorded in notes and on other appropriate forms. In fact, every individual who has occasion to possess the evidence must maintain a written record of its acquisition and disposition. Frequently, all of the individuals involved in the collection and transportation of the evidence may be requested to testify in court. Thus, to avoid confusion and to retain complete control of the evidence at all times, the chain of custody should be kept to a minimum.

Documentation of Evidence

The first step of proper evidence collection is thorough documentation. Descriptive notes and observations should be recorded as soon as possible. The healthcare professional should make note of the condition in which the patient arrived, as well as how and when the patient came into the emergency department. If possible, appropriate personnel should be encouraged to photograph the patient and each specific injured area before the patient receives medical treatment. However, it goes without saying that the foremost concern is with the patient’s health and well-being. No forensic protocol must be permitted to inhibit a patient’s care. Nevertheless, sensitivity on the part of attending medical personnel to potential forensic investigations may prevent the unnecessary destruction of vital evidence. If photography is a reasonable undertaking, one should avoid cleaning the wound area before it is photographed. A patient’s consent should be obtained before the photographs are taken. By doing this, legal complications regarding inadmissibility of evidence can be avoided. When a patient is unable to verbally consent, possibly one can obtain consent from a relative. It is important that whoever gave the consent and that person’s relationship to the patient are documented.

Photodocumentation

Currently there are two methods or approaches to forensic photography: film and digital photography. There are obvious differences between the ways film and digital imaging technology record scenes, notably the methods by which each type of photography converts light into an image. Photographic film consists of a sheet of light-reactive silver halide grains and comes in several varieties. A digital photograph is made when a light-sensitive microchip inside the camera is exposed to light coming from the object or scene you wish to capture. The light is recorded on millions of tiny picture elements, or pixels, as a specific electric charge. The camera reads this charge number as image information, then stores the image as a file on a memory card.

Although the general public is more familiar with digital “point and shoot” cameras, single lens reflex (SLR) or digital single lens reflex (DSLR) cameras are required for photographing a patient. Both kinds of SLR cameras allow for the use of a wide range of lenses, flashes, and filters. Further, SLR and DSLR cameras give photographers the option of manually selecting f-stop, shutter speed, and other variables associated with photography. Digital photography is rapidly becoming the method of choice in the field of forensic science.

The very nature of digital images, however, opens digital photography to important criticisms within forensic science casework. Because the photographs are digital, they can be easily manipulated by using computer software. This manipulation goes beyond traditional photograph enhancement such as adjusting brightness and contrast or color balancing. Because the main function of forensic photography is to provide an accurate depiction, this is a major concern. To ensure that their digital images are admissible, many jurisdictions set guidelines for determining the circumstances under which digital photography may be used and establish and enforce strict protocols for image security and chain of custody.

Photographs of the patient should include the face, along with the injured areas. A photo log should be kept and should include pertinent information such as a patient’s name, date, time, photographer’s name, type and speed of film, and the specific exposure numbers. Some digital cameras produce an electronic photography log. This log must be submitted along with notes and a handwritten photography log.

When an injured area is photographed, an object of measurement should be included for delineating the size of the injury. For example, placing a quarter next to a bullet hole will allow an investigator to easily interpsret the size of the hole when the photographs are viewed at a later time. More ideally, an American Board of Forensic Odontologists (ABFO) ruler should be employed (see Chapter 7). As the condition of the injured area changes, subsequent photographs should be taken to reflect such changes. Remember that the film and photographs will become part of the chain of custody. Therefore, they should be handled and documented in the appropriate manner. Along with photographs, handwritten notes describing injuries should also be taken.

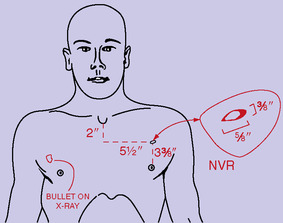

Anatomical charts and diagrams

An anatomical chart is a handy tool to record all of the marks on the body (Fig. 6-1). The description of each mark must include size, shape, color, location, and the characteristics of the edges around the wound. Also, a notation should be made about the presence of any foreign material in or around the wound. Emergency department personnel are often one of the first human contacts a patient will encounter. Verbal statements made by the patient should be recorded using quotations. The value of thorough documentation will prove significant later on during the investigation into what occurred. An inventory list that includes what items were collected, the time and location of collection, the name of the person who performed the collection, and the name and badge number of the officer who received the evidence should be maintained.

Evidence Kits

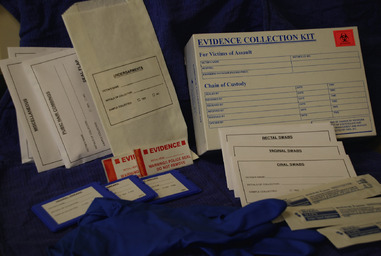

Commercial evidence collection kits are a convenient and useful means for assuring the availability of appropriate evidence containers. Commercial evidence containers will also have appropriate chain of custody information printed on the outside of the container. The kit normally includes a variety of small metal cans for the collection of debris, paint chips, glass particles, or metal fragments. Paper envelopes of different sizes are present to package bullets, cartridge cases, or hairs and fibers. Zipper-locked plastic bags provide packaging for soil samples, drugs, or dried plant materials. Evidence seals are an important component of the kit. They allow for the sealing of the various containers within the kit so that evidence tampering is not possible. Any attempt to gain access to the container will require the obvious breaking and disruption of the seal (Fig. 6-2).

Evidence on Clothing

The recognition of physical evidence is not always an easy task. Often, materials that are transferred from one object to another will only exist in trace amounts. However, by learning to recognize where and how such exchanges take place, emergency room personnel can aid in the collection and preservation of potential forensic evidence. In a hospital environment, there probably is no more important an item of physical evidence than the patient’s clothing. For example, a shooting victim’s clothes may contain a multitude of information. When a bullet penetrates a piece of clothing, characteristic material is usually deposited on the garment. Partially burned and unburned gunpowder particles can be scattered around the bullet hole. The shape and distribution of these particles reveals information about the distance between the firearm and the victim. For example, a shooting victim may claim he or she was intentionally attacked. However, the assailant may claim the shooting was in self-defense and ensued during a struggle. Careful examination of the clothing surrounding the bullet hole may give some important clues. A minute amount of gunpowder residue given off by a firearm may refute the self-defense theory and suggest the weapon was fired at a significant distance between the firer and the target. Even in situations where no gunpowder residue is deposited on the garment, important information can be obtained from a dark ring, known as bullet wipe, surrounding the bullet hole. Bullet wipe is composed of material transferred from the surface of the bullet onto the target as the bullet passes through the fabric (Fig. 6-3).

Another piece of significant evidence that can be retrieved from bullet holes in clothing are the rip patterns caused by a penetrating bullet. When a firearm discharges within direct or very close contact with material, a star-shaped rip pattern may characterize the bullet hole. Often, fibers surrounding the hole made by a contact or near-contact shot will be scorched or melted as a result of the heat from the discharge. Cuts in clothing arising from sharp objects such as a knife blade contain important forensic information. Careful laboratory examination may reveal the type of knife blade used or it may reveal whether the assailant hesitated while inflicting the knife wound.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree