IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

Policy problems addressed through federal–state relations in health usually centre on ‘fiscal squabbles’, ‘waiting’ and ‘waste’. ‘Fiscal squabbles’ break out between different levels of government when one level tries to shift costs to another or, alternatively, seeks to minimise its contributions to funding health services. Much of the politics and negotiation between the federal and state governments involves deciding who has fiscal responsibility for various health functions and programs and then developing mechanisms to ensure that each level of government meets its agreed responsibilities for funding.

‘Waiting’ drives much of the politics of health. The public, through the media, is primarily concerned about access to services (particularly acute hospital services). As Kingdon has stressed, indicators frequently identify problems requiring policy intervention (Kingdon 1984). When indicators of access suggest services are unavailable, unaffordable, very distant or require a long wait governments come under pressure. Not surprisingly, professional groups and service providers often fuel these debates. Given the Australian and state governments share responsibility for service provision, they then share responsibility for criticisms over access to services. As with cost shifting, there is a tendency for each level of government to blame the other for access problems. In addition to the fiscal rules, health agreements between the Australian and state governments often have a heavy emphasis on defining responsibilities for demand and access to services.

‘Waste’ is a proxy for inefficiency, fragmentation and duplication in the delivery of health programs. At its worst, this leads to significant concerns about quality. Often discontinuity and conflict between the Australian and state governments is blamed for poor health outcomes and inefficient use of resources. A significant drive to improve the productivity, quality and effectiveness of the health system underpins inter-governmental negotiations.

In this chapter we approach analysis of these policy problems by focusing on how inter-governmental relationships within the federal system affect the design and implementation of particular health programs. It is our view that coordination across programs and the boundaries between them is the most fruitful area of analysis in addressing the problems we have briefly outlined above.

However, before moving to a more detailed discussion of program coordination and boundaries and policy options for addressing them, we need to consider how federal and state government responsibilities are distributed and what mechanisms have been put in place to manage federal–state relationships.

THE CURRENT DISTRIBUTION OF FEDERAL AND STATE GOVERNMENT RESPONSIBILITIES

In Australia, total health expenditure has grown rapidly over the past decade. In constant prices, expenditure has increased by $31 billion and 1.7% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the decade from 1994–95 to $87.5 billion and 9.8% of GDP in 2004–05. Estimated health expenditure was $4319 per person, up from $2797 10 years earlier (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2006).

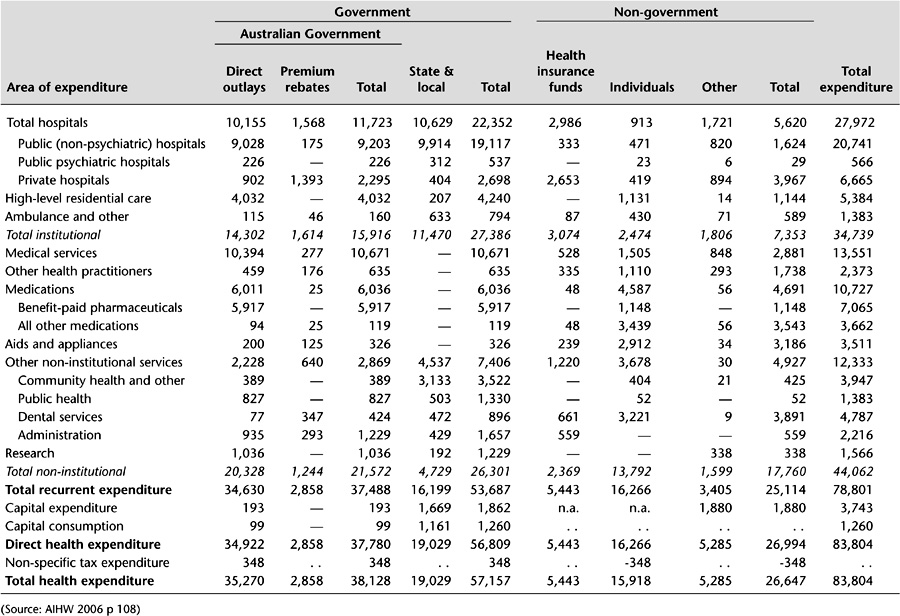

Table 6.1 shows the distribution of health expenditure for different areas of activity for 2004–05. Of the total, 42% went to hospitals and residential care. Non-institutional services made up 53% of total expenditure. Only 1.5% was spent on public health programs to promote health and prevent illness and disease.

Table 6.1 Total health expenditure, constant prices, Australia, by area of expenditure and source of funds, 2004–05 ($million)

The Australian government is by far the most significant funder of health services. In 2004–05, the federal government provided 45.6% of the funding, states and territories 22.6%, individuals (out-of-pocket expenditure) 19%, health insurance 6.5% and other non-government sources (including injury compensation agencies) 6.3% (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2006). These shares are unevenly distributed across programs.

The federal government has primary responsibility for funding primary and specialist medical services through the Medicare program. In practice, the states and the Australian government jointly regulate medical services through registration bodies and the policy and compliance provisions of the Medicare program. Inpatient and outpatient medical services in public hospitals are the responsibility of the states. The federal government provides a Medicare subsidy for medical services provided in private hospitals.

The states are primarily responsible for providing a range of public health, primary health, and community care services, including maternal and child health, school health, community health, mental health, and alcohol and drug services. More recently, the Australian government has augmented these primary care services through Medicare and by directly funding non-government agencies for allied health services.

The federal and state governments jointly fund home and community care for frail older people and younger people with disabilities through the Home and Community Care (HACC) Agreements and the Commonwealth State Disability Agreements. The states are primarily responsible for the operation of the services covered by these agreements, although the Australian government retains responsibility for providing employment services for younger people with disabilities.

While in Australia government provides the majority of funding for most mainstream health programs and services, this is not the case for oral health. Individuals pay the majority of the costs of these services themselves. The states provide limited public oral health programs for children and low-income adults. Almost no funds for public oral health services are provided from federal sources.

The Australian government has the major responsibility for funding the provision of pharmaceuticals in primary and community care settings, and meets the lion’s share of pharmaceutical expenditure (85% for prescribed medications). Pharmaceuticals are provided to consumers through the Pharmaceuticals Benefits Scheme (PBS) with a mandatory co-payment and a safety net where total annual expenditure exceeds preset limits. Safety and quality of pharmaceutical products and other therapeutic goods are managed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Pricing by pharmaceutical companies is regulated through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). States are responsible for the provision of inpatient pharmaceuticals in public hospitals with some exceptions for highly specialised drugs. Responsibility for funding outpatient pharmaceuticals in public hospitals varies between the states. The Australian government, consumers and health insurers have joint responsibility for funding pharmaceuticals in private hospitals.

The states have primary responsibility for operating and regulating public hospitals. Funding is provided jointly by the federal and state governments through the Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA). These 5-year, bilateral agreements are designed to provide universal, free public hospital care on the basis of clinical need to all Australians, regardless of location. They set the national framework for public hospital services.

The federal and state governments have very different emphases in terms of their respective expenditure patterns. Public hospitals and community and public health services are the main objects of state government expenditure: these two items together account for almost three-quarters of their health expenditure. The main objects of federal government expenditure are medical benefits (28% of its funding), public hospitals (25%), pharmaceutical benefits (16%), and high-level residential care (nursing homes, 11%). This different expenditure pattern leads to different emphases in policy focus and attention, discussed further below.

Australian and state government funding, regulation and operation of health programs is a mosaic of overlapping and blurred boundaries. Much of this reflects the history of federal–state relationships through Australia’s unique form of federalism. The next section outlines the institutions of Australian federalism.

POLICY RESPONSES: THE INSTITUTIONS OF FEDERALISM

The Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia (Parliament of Australia 1987), drafted last century, defined the relationship between the national government and the states to limit the powers of the former and to make these powers difficult to change. Where the Australian government had powers, it was intended that these should prevail over the powers of the states. But the states retained sovereignty over areas where the national government had no jurisdiction. Unlike the United Kingdom, where the national parliament is able to resolve constitutional questions, in Australia the High Court was established as the vehicle for adjudicating in disputes about the powers of the Australian government, thereby inevitably placing the High Court in a quasi political and legislative role (Davis et al. 1988).

As economic and social pressure on the Australian state has become more complex, the federal government has progressively sought to extend its powers. Section 96 of the Constitution gives it power to provide general and specific purpose payments to the states as it sees fit. In order to exercise that power it must have the fiscal wherewithal to force the states to the table. It achieved this by restricting state borrowing powers through establishing the Loans Council in 1927 and by its acquisition of universal income tax powers in 1942 (Rydon 1989). The Australian government has progressively gathered significantly more revenue than it spends for its own purposes, while the converse is true for the states – a situation known as ‘vertical fiscal imbalance’.

The states have therefore become dependent on the Australian government for specific-purpose payments made through federal–state agreements to provide services. In health and related areas these include the Australian Health Care Agreements, the HACC Agreements and the Commonwealth State Disability Agreements. In 1999 an Intergovernmental Agreement on the Reform of Commonwealth–State Financial Relations established a Goods and Services Tax (GST) implemented federally to provide the states with a revenue stream. Funds from the GST flow to the states on the basis of relativities determined by the Commonwealth Grants Commission. The GST is a growth tax which largely replaces previous financial assistance grants made by the national government to the states. It also places a set of specific state government taxes. In part, the intention of the GST is to provide a more certain fiscal environment for state governments.

Notwithstanding the introduction of the GST, the own-purpose expenditure of the states continues to exceed their own-purpose revenue. Currently, it would be difficult for the states to replace federal government contributions in major agreements, such as the AHCA and HACC, from their own revenue streams. Therefore they have only limited ability to resist the national government’s fiscal directives in health-related Special Purpose Payments (SPPs).

The Australian government’s powers have been increased through judicial decisions and constitutional referendums. While referendums have generally been unsuccessful, two of the eight that have been carried since federation were vital for extending the federal government’s ability to develop national social policy. The most important of these, the creation of section 51xxiiiA in 1946, allowed for:

the provision of maternity allowances, widows’ pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorise any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances.

In the second case, the successful 1967 referendum to amend section 51xxvi allowed the Australian government to make laws for Aboriginal people.

High Court decisions

As Rydon notes, the Constitution is not clearly worded and there is considerable scope for interpretation (Rydon 1995). As a result, in a number of cases High Court decisions have also extended the federal government’s powers to make laws in relation to social programs. For example, the Australian government has been able to use the external affairs power to enter into international agreements and then legislate and create programs in areas where previously it had no direct powers.

In combination with the original constitutional powers over quarantine, marriage and divorce, invalid and old-age pensions, immigration and emigration and ‘the influx of criminals’, these new powers form the basis for the Australian government’s ability to create and administer its own social programs. As well, section 96 gives the Australian government power ‘to grant financial assistance to any state on such terms and conditions as the Parliament thinks fit’. This section has formed the basis for gaining state agreement to federal government policy objectives where the national government’s powers are absent or difficult to exercise for practical or political reasons. It has been particularly used to circumvent the constitutional limitation on the nationalisation of key sectors of social and economic activity which is set out in section 92.

Most recently the Australian government has won a major extension of its powers when the High Court decided in relation to Workplace Relations Case (Roth & Griffith 2006) that the national government has a broad power to regulate foreign, trading or financial corporations. Many health institutions, particularly public hospitals and larger community health agencies, are corporations and the federal government therefore appears to have the power to regulate any aspect of what they do.

Nevertheless, although the Australian government’s power has grown, its dominance is not absolute and constitutional ambiguity and the interpretative powers of the High Court ensures an inherently flexible, emerging and contested relationship between the federal government and the states. For many important areas of national social and economic policy, the Australian government requires the agreement of the states to achieve change. Moreover, in a number of cases, where the constitution gives neither level of government dominance, dual systems of federal and state administration, funding and provision have developed. In the face of changing social and economic conditions federalism is continually being reinvented. Not surprisingly, a number of coordinating and negotiation structures have arisen to deal with these uncertainties.

Federal–state councils

Most importantly, federal, state and territory heads of government meet annually (since 1992 called the Council of Australian Governments, COAG) to consider a range of federal–state matters of national importance. In 1999, the Ministerial Council for Commonwealth–State Financial Relations (Treasurers Conference) was established as part of the Intergovernmental Agreement to Reform Commonwealth–State Financial Relations. The council considers overall fiscal policy, revenue shares and federal payments to the states and territories, including the GST and SPPs.

Similarly federal, state and territory portfolio ministers meet annually as ministerial councils to consider specific policy issues. In this respect, for example, the Australian health ministers’ and community services ministers’ councils are central to the resolution of national policy disputes regarding the development of specific social programs such as those which relate to continuing care services for people with psychiatric illness, frail older people and those with disabilities.

Given its constitutional limitations, which necessarily fragment legislative and administrative responsibilities for significant social and economic functions across levels of government, the national government is forced to negotiate with the states and territories through these forums when it wants to initiate major reform proposals which cross-jurisdictional boundaries. While the Australian government is able to wield significant fiscal power and use its national voice in direct appeals through electoral processes, the states and territories nevertheless have significant capacity to frustrate the federal government by refusing to cooperate. Clearly when differing political parties are in government at the national and state levels, particularly in the most populous eastern seaboard states, these problems are accentuated.

The previous sections have outlined the broad context for understanding federalism and health. However, the issues come alive for health consumers when they try to access particular services. The way services operate is determined by the programs which each level of government provides. Programs are the currency for discussing federal–state relations in health. Both levels of government organise their funding, regulation and direct provision of services through programs. Programs have goals, objectives, funding and accountability mechanisms, guidelines and regulations. As outlined above, the Australian federation ensures that each level of government has sovereignty in the way it designs its programs. The problems of federation (and the actual experience of consumers) are then the problems of program boundaries and coordination.

PROGRAM BOUNDARIES AND COORDINATION

Program boundaries are an inevitable consequence of public sector program design. In order to ensure appropriate parliamentary accountability of expenditure, programmatic rules need to be developed to determine what services will be funded, what people will be eligible, and in the case of ‘special appropriations’, rules also need to be developed about how much will be paid for each service or product. These rules inevitably create problems at the margin. With income-support schemes, rules can create poverty traps and very high effective marginal rates of taxation if a low-income person earns additional income. Service delivery programs create equivalent gaps and perverse incentives and so it is not possible to design a service system with no problems of service coordination and transitions across boundaries. The quixotic quest for a perfectly coordinated system ignores the service reality: strengthening some interrelationships necessarily weakens others. Strong coordination of community and inpatient mental health services inevitably implies weaker links between community mental health and generalist community services and between inpatient psychiatry and other inpatient services. As Leutz paraphrased Abraham Lincoln: ‘You can integrate some services for all of the people or all services for some of the people but you can’t integrate all services for all of the people’ (Leutz 1999).

But this is not to say that policy should not attempt to minimise the perverse impact of program boundaries. Programmatic boundary issues can be characterised as being of two kinds:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree