CHAPTER 6. Exchanging information

• Introduction

• Two strategies for exchanging information

• A case example of exchanging information

• How does information relate to importance and confidence?

• How is information exchange different from giving advice?

Exchange information

1 Would you like to know more about…?

2 How much do you already know about?

3 The test result is… X, what do you make of this?

4 What happens to some people is… and… What about you?

5 How do you see the connection between X and Y?

6 Now that I have given you this information, how does it apply to you?

7 Take me through a typical day in your life, and tell me where your [behavior] fits in? …So, on Monday, you woke up, how were you feeling? …Then what did you do? …You’re going a bit fast for me! Can I take you back to when you left the house on Monday morning… What happened then, and how did you feel?

Introduction

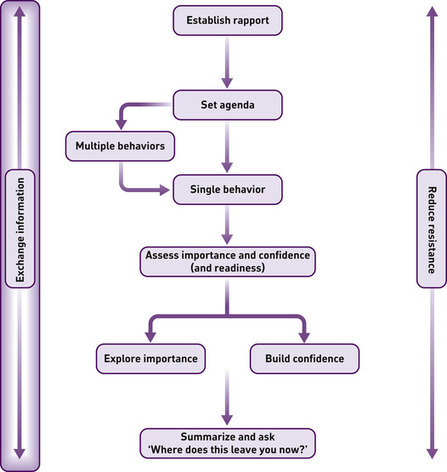

There are two tasks that a practitioner might need to perform at various stages throughout a consultation: exchanging information with the patient and responding constructively to resistance. This chapter describes the first.

An overweight young woman is referred ‘for dietary and fitness advice’. She sits down by your desk a little apprehensive and expectant. The overall task, as you both know, is to set her on the path to successful weight loss. You need to know some key things about her before you can imagine what might work for her. She is expecting you to give her information about diets and exercise. You expect that she has probably dieted before and has some knowledge and ideas about how to do it. You need to know how much she already knows and how accurate her existing information is. You want her to leave the consultation with all the accurate information she needs to make a success of a weight-loss program.

A middle-aged man has been diagnosed with liver disease. You need to discuss with him the importance of stopping drinking alcohol. You don’t know whether he already realizes that he needs to think about his drinking. You don’t know what part alcohol plays in his life and how much he would mind giving it up. You know a lot about strategies for giving up drinking and places he could get support, and you would like to give him as much of this information as possible.

A large part of the practitioner’s role is giving information to the patient. A large part of the patient’s role is giving information to the practitioner.

Done badly, this task will make the patient a passive recipient of expert knowledge, disconnected from his or her context and concerns. Done well, it is a vehicle for true understanding and, it appears, a better outcome. For the practitioner, information exchange will be linked to specific medical or behavioral matters. For the patient, it often also includes broader personal concerns. To deal with the former at the expense of the latter can be a serious mistake. Improving various aspects of the information exchange process can enhance the congruence between patient and practitioner, and encourage the patient to think positively about change. This is not just a ‘technical matter’ or an exercise in the exchange of facts, but something that involves the use of skillful listening, careful questioning, and well-timed intervention. There are few parts of the consultation that do not involve the eliciting or providing of information.

Studies of communication reveal that the way in which practitioners exchange information can be strikingly one-sided and, at times, insensitive. For example, one study found that practitioners interrupted patients an average of 18 seconds into their initial description of the problem; in another study, patients and practitioners did not agree on the main presenting problem in 50% of outpatient consultations (Starfield et al 1981).

Given its obvious importance, it is something of a surprise to notice that information exchange is seldom taught as a specific topic in its own right. It is difficult to find clear and teachable strategies that help practitioners to carry out this task. Rather, they are left to find their own ways of doing this. The purpose of this chapter is to bring together what we understand as the most effective and satisfying way to exchange information, in a form that can be learned and practiced. This is not only relevant to behavior change consultations. It also applies to other kinds of consultations, such as when breaking bad news, talking about diagnoses, and so on.

The lack of progress in developing such methods is not just a practical problem, but also a conceptual one. Information exchange has been too readily viewed as a one-sided process, hence the emphasis in both research and practice on either assessment (getting information from the patient) or feedback (giving information to the patient); both of which are activities derived mainly from the agenda of the practitioner. The education of medical and other students is usually guided by this kind of one-sided approach. As the strategies described below will reveal, the conceptual framework being used is explicitly two-sided, where the practitioner also encourages the patient to drive the discussion at certain points in the exchange process. Thus, the patient will not only be assessed and receive feedback, but will also express his or her information needs and be encouraged to arrive at a personal interpretation of the information received.

Conceived thus, information exchange is a skillful task which will benefit from further development work and careful attention to the process of how best to improve practice. The practical strategies below come from two sources: first, the study of communication and the patient-centered method, and second, motivational interviewing.

The patient-centered method

Research on communication reveals, as one might expect, that practitioners vary considerably in how they exchange information, and that outcome can be improved if information is clear and simple, and if practitioners negotiate and agree on treatment goals in a cooperative manner (Becker 1985). Although these findings are obviously useful, much of the research on compliance is based on the notion that behavior change is best ‘induced’ by the expert-driven delivery of clear information, a view we explicitly reject (see Butler et al 1996).

Of more direct relevance, has been the work on patient empowerment and the patient-centered method carried out by a number of North American research teams. Not all of this research focuses on information exchange, although a number of studies, reviewed by Stewart (1995), have looked explicitly at the process of history-taking. Four correlational studies, all of them in outpatient settings, reveal that during history-taking, activities like a full discussion of the problem, the asking of questions by the patient, providing information, and giving emotional support are all associated with better outcomes, such as the resolution of headaches and numerous other physical symptoms. Two randomized controlled trials found that practitioner training in history-taking improved levels of psychological distress in patients, and another two studies found that brief patient education (20 minutes) in how to ask questions not only improved participation but led to improved physical health such as control of blood pressure and blood glucose levels.

Of course, information exchange does not only occur during history-taking. A number of other studies of patient empowerment have involved the training of patients to be more assertive in other phases of the consultation. Thus, Innui et al (1976) found that giving patients greater control over what is talked about and encouraging them to seek personally relevant information can improve outcomes like control of blood pressure. Greenfield et al (1988) demonstrated that people with diabetes who were trained to be more involved in the consultation had better health outcomes than those who were not trained. Similarly, patients seen by health educators and coached to ask questions made better use of appointments over the following months (Roter 1977). Therefore, this approach is by no means new, conceptually. The challenge has been to translate research findings into better practice across the board.

Finally, it is worth taking note of Silverman’s (1997) observation of a feature of advice-giving which avoids being too personal and eliciting resistance: if the advice is couched in terms of information, i.e. in a broader, more neutral context, patients seem more likely to respond favorably.

In summary, there is clear evidence that if patients are more assertive during information exchange, outcomes can be improved. There is much less evidence that practitioners can be trained to improve their skills. There are clear correlations between elements of good-quality information exchange and patient outcome.

Motivational interviewing

A second source of innovation comes from the work of William R. Miller on motivational interviewing in the addictions field. He found a way of training counselors to encourage curiosity, question-asking and personal reflection among clients about the meaning of information provided to them. This process, it turns out, can have a powerful effect on people’s decision-making. It appears that this is not just a matter of presenting appropriate information clearly to people, but of distinguishing between ‘facts’ and their interpretation. In these drinkers’ check-up studies (see Miller & Sovereign 1989), the counselor provided the facts in a non-judgmental, neutral manner, and then encouraged the patient, through the use of simple open questions, to arrive at a personal interpretation of them. More detail about this process can be found in Miller et al (1988). The ideal outcome would be for the patient to say or think, I see, I never thought about it like this before, I wonder if this means that…Strategy 1, outlined below, is based on this aspect of motivational interviewing. It was refined further in the development of brief motivational interviewing (Rollnick et al 1992), where a clearly defined and documented information exchange strategy was taught to a group of general healthcare workers doing health promotion work with heavy drinkers in a general hospital (Heather et al 1996). Rollnick et al (2008) devote a whole chapter to the skills of informing in the context of motivational interviewing in a healthcare setting, and note that, ‘a relationship, even if it lasts no more than a few minutes, lies at the heart of informing’ (p. 88).

What emerges from these developments is a view of information exchange as part of a delicately balanced conversation. It does not need to be a sterile, expert-driven activity. From a conceptual viewpoint, we do not adhere to the view of information exchange as a practitioner-driven process either of eliciting facts from patients (assessment) or of providing them with information (feedback). In both such activities, the patient will be driven along by the agenda of the practitioner, who will do most of the talking. Instead, we view the process in terms of the following circular elicit–provide–elicit process described below (Strategy 1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access