CHAPTER 5. Exploring importance and building confidence

• Introduction

• Five strategies for exploring importance

• A case example of exploring importance

• Five strategies for building confidence

• Reminders on action planning

• A case example of building confidence

• Overlapping of importance and confidence

• Conclusion

Explore importance

1 What would have to happen for it to become much more important for you to change?

2 What would have to happen before you seriously considered changing?

3 Why have you given yourself such a high score on importance?

4 What would need to happen for your importance score to move up from X to Y?

5 What stops you moving up from X to Y?

6 What are the good things about… [current behavior]? What are some of the less good things about… [current behavior]? [Alternative: things you like and dislike…]

7 What concerns do you have about… [current behavior]?

8 If you were to change, what would it be like?

9 Where does this leave you now? [When you want to ask about change in a neutral way]

Build confidence

1 What would make you more confident about making these changes?

2 Why have you given yourself such a high score on confidence?

3 How could you move up higher, so that your score goes from X to Y?

4 How can I help you succeed?

5 Is there anything you found helpful in any previous attempts to change?

6 What have you learned from the way things went wrong last time you tried?

7 If you were to decide to change, what might your options be? Are there any ways you know about that have worked for other people?

8 What are some of the practical things you would need to do to achieve this goal? Do any of them sound achievable?

9 Is there anything you can think of that would help you feel more confident?

Introduction

Patient 1: Maybe I will quit one day, maybe I won’t. Giving up is not really a problem. I’ve done it before without any problem whatsoever. I enjoy smoking and it doesn’t seem to be doing me any harm. I know I shouldn’t smoke in front of the children, especially little Maria with her bad chest. I don’t suppose it sets a very good example. Still, my granny smoked 80 a day for 60 years and got run over by a bus while she was running across the road at the age of 85! I just enjoy smoking and it doesn’t worry me.

Some patients attach a low importance to behavior change.

Patient 2: It’s no good me trying to stop smoking. I know what you’re saying is right. I ought to and I’ve tried lots of times but I’ve got no willpower. I last a couple of weeks and I’m back where I started.

Patient 3: I really can’t see myself being able to remember to take this inhaler three times a day. It’s easy to remember when my chest is bad. But when I feel better, I just forget completely although I know it’s important to prevent my asthma attacks. I’m just not organized enough to do it.

Other people have so little confidence that it doesn’t seem worth their even trying.

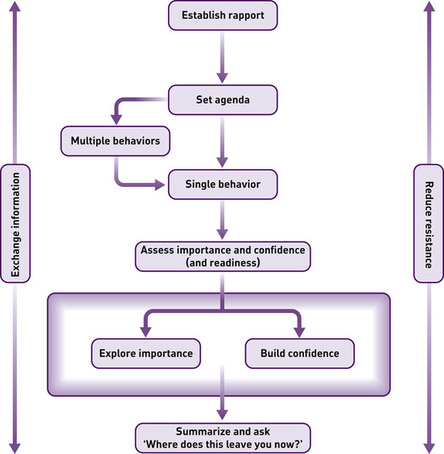

Having assessed the importance of change for patients and their confidence to put plans to change into action (see Chapter 4), you reach a critical junction. You need to decide where to go next, and whether to focus on importance or confidence. This chapter summarizes a selection of strategies for working within either dimension. Usually, it is most productive to work on whichever seems to be lowest. For each of these topics, importance and confidence, we have constructed a menu of strategies. Which one to use depends very much on the circumstances, your aspirations and the needs of the patient.

The delicate dance

In moving both within and between these dimensions, the practitioner will require all the skill and deftness of a dancer leading a partner through a sequence of movements, simultaneously leading and being led, keenly alert to subtle threats to the synchrony of the partnership. Resistance from the partner is not met by force, but by transforming the movement in a constructive direction, if at all possible. No amount of dedicated adherence to the strategies described below will be effective if this state of mind is absent. The strategies are merely aids to avoiding collision, like the steps one learns in a dancing class.

A certain degree of relaxation is required to maintain this spirit in the consultation. As noted earlier in this book, we have found it useful to develop a committed but curious state of mind when talking about behavior change. There is no sense in which you can be expected to have all the answers. Indeed, if you are to work within the spirit of this approach, you must believe that these lie mostly within the patient.

Five strategies for exploring importance

Five strategies are described in this section, all of which are options for exploring importance:

The range of strategies for exploring importance is best viewed as a menu from which you select one to suit your needs. Indeed, we suggest that if you have time for development work, you adapt these strategies and construct new ones more appropriate to your client group.

Care should be taken not to view these strategies as techniques applied to or on patients. If this happens, it is an indication of detachment which we presume will damage rapport. The strategies are simply ideas for structuring a purposeful conversation. Their specificity should also not be misunderstood; this is intended as a guide, as a concrete reference point which we know is likely to minimize resistance. As noted from the outset, creative adaptation, not slavish adoption, should be the goal.

Tailoring the strategy to the patient

Some of the strategies for working on importance are best used at fairly high levels of this dimension (i.e. with scores above 5/10 on the formal assessment). This applies particularly to exploring concerns; for example, if a patient does not see change as particularly important, and you use a strategy like exploring concerns, you could be in trouble! The patient will say, What concerns? The same logic applies to the hypothetical look over the fence. Others are safer or more widely applicable at all levels of importance: for example, scaling questions, and examining pros and cons. The strategies below are thus presented in ascending order of suitability to patients, from lower to higher levels of perceived importance.

Your use of words to describe different degrees of concern about a behavior can be critical. If a patient says, My drinking is sometimes a problem, and you respond reflectively with, You think you might be becoming an alcoholic, you could elicit resistance. If you give people a chance to talk, they will use a variety of words about change. You should watch out for these and match them as far as possible. Many of the strategies below start with a leading question that implies knowledge of how concerned the patient is about a behavior. Sometimes, however, one does not get a lead from the patient, and one has to take a deep breath and see what happens.

We have noticed that if one imagines a continuum of importance, from 0 to 10, different words are suitable at different points along this continuum. The wording, What is it you don’t like about [behavior]? is the safest bet, applicable for most people, provided that the level of reported importance is not 0. In ascending order, the following terms are appropriate, as the level of importance gets higher: dislikes or less good things (2–3/10 or above), concerns (6/10 or above), and difficulty or problem (7–8/10 or above). When you are paying close attention to the way the patient is talking, their choice of words and body language, you will be able to choose intuitively the right way to phrase your inquiries.

Strategy 1. Do little more

If a patient’s level of perceived importance is markedly low, particularly if accompanied by a low level of confidence, it might be advisable to close the discussion of behavior change and either turn to an issue they consider more important or end the consultation. How this is done is important. You could leave the patient feeling downhearted or even reluctant to come back and see you again. Consider saying something like:

Perhaps now is not the right time to talk about this? How do you feel?

You say you are unsure about what to do. I do not want to push you into a decision, it’s really up to you. I suggest that you take your time to think about it.

I have met other people who have felt just like you do. Some, for good reasons of their own, decide not to do anything for the time being. Others do the opposite and make the change. You will be the best judge of when is the right time to consider change. Is there some other issue that feels more important to you?

Whatever you do, acknowledge the uncertainty, do not just leave the patient hanging in the air. If you are not sure what to do, ask the patient. For example, he or she might want to talk about it again on another occasion when other priorities have subsided: I would like to talk about losing weight sometime but just now I’m so worried and stressed looking after my Mum while she’s sick, I just can’t think about it.

Many practitioners faced with this situation are tempted to take a deep breath and simply provide information, seeing it as their professional responsibility to at least inform the patient of existing or potential risks. If this does not damage rapport, the approach seems understandable and justified. Chapter 6 discusses an approach to doing this.

Strategy 2. Building on the scaling questions

This involves using a set of questions designed to understand and encourage the patient to explore the whole question of the personal value or importance of change in more detail. It builds on the numerical assessment described in Chapter 4 (adapted from work by de Shazer et al 1986), although it can also be used in a non-numerical form. Typically, having elicited a numerical judgment of importance, the set of simple questions noted below can open up a very productive discussion in which the patient is doing most of the talking and is thinking hard about change (see Rollnick et al 1997).

You have already conducted an assessment of how important it is to the patient to change, and you have a given level, ideally a number, in mind although this is not essential. You can then ask open questions along the lines of: Why so high? How can you go higher? What would it take to move you up a step? What number would you need to be on before you would give it a go?

The aim of these questions is two-fold: first, for patients to better understand their own points of view and to hear themselves speaking positively about change as something that might, at some point, be desirable or possible. Second, for you, the practitioner, to better understand the key issues for patients and their current attitudes to change. To achieve this, ensure that the pace of the discussion is slowed down, and develop a genuine curiosity to know how this person really feels. You should listen to the answers to your questions, using techniques like reflection and other simple open questions to help patients express themselves as fully as possible. Your attention should not be on your own thought processes, What should I say next?, but as much as possible on the meaning of what the person is saying, What exactly is it they are telling me? Trust the process and the patient. Watch carefully for resistance, because this is a signal that you are going too far or too fast.

Why so high?

Ask why he or she scored a given number and not a lower number. For example:

You said that it was fairly important to you personally to change [behavior]. Why have you scored 6 and not 1?

The answers amount to positive reasons for change, or in the jargon of motivational interviewing, change talk (Miller & Rollnick 2002). For example:

I am at 6 and not 1 because I cannot go on like this forever.

An obvious response is simply to ask Why not? or What concerns you most about continuing as you are in the long term?

Your task is now to elicit the range of reasons why the person wants to change. The pace should be slow, and simple open questions can be very useful. If the answers are obvious, elicit them and move on. If more complex, take your time trying to understand all the ramifications. If the patient gave the importance a level of 0 or 1, you would probably choose not to use this strategy! However, even with a 2 you might say:

So it’s obviously not a high priority for you. However, you gave it a 2 and not a 1 or 0. I thought you might put it right down the bottom of the scale but you didn’t. It sounds as if a little part of you attaches some importance to it? What’s that about?

Can you see how different it would be if you asked, Why is it only as low as that? This would invite negative statements about change and encourage patients to identify with the resistant side of the ambivalence.

Having elicited some change talk, explore it, reflect it, ask for more reasons why and ask for specific examples.

How can you go higher?

A second kind of question moves in the opposite direction, up the scale from the number given by the person. For example:

You gave yourself a score of 6. So it’s fairly important for you to change [behavior]. What would have to happen for your score to move up from 6 to 9? or How could you move up from 6 to 8 or even 9? or What stops you moving up from 6 or 7 at the moment?

Note that one can ask about either your score or just you. The second often feels better. In answering these questions, the patient opens up the possibility that change might be an option at some point, perhaps if things were a bit different. It also helps the practitioner to understand the obstacles or barriers to change.

Here is an example of dialog which illustrates that the key challenge for the practitioner is to carefully follow the patient’s response, with further questions and reflective listening statements. In this example, the practitioner starts with the first kind of question described above: Why so high?, and then simply follows the responses of the patient. It is not necessary in this example to move on to using the second kind of question: How can you go higher? The conversation flows quite naturally into that territory; what would make the person more motivated? Note how the use of a new strategy involves being quite directive to begin with; the practitioner offers a structure to the conversation.

Practitioner: [A few minutes into the consultation. Decides that the patient will respond to a quick assessment of importance and confidence] How do you really feel about taking more exercise? If 0 was ‘not important to you at the moment’ and 10 was ‘very important’, what number would you give yourself?

Patient: [A short silence] About 6.

Practitioner:And if you did decide now to take more exercise, how confident are you that you would succeed? If 0 was ‘not confident’ and 10 was ‘very confident’, what number would you give yourself?

Patient:About 8.

Practitioner:So if you decided to do it, you feel fairly confident, but you are not sure how important it is for you right now.

Patient:Well yes, that’s about right.

Practitioner:You said it was fairly important for you, a score of about 6. Why did you give yourself 6 and not 1?

Patient: [Initial silence] I am at 6 and not 1 because I know I need to make my heart work harder in order to get it strong again. I understand the logic of that. If I had broken my leg, I’d do physio to get better again. Now that I have had a heart attack, I guess I should go back to my walking and swimming.

Practitioner:It will be good for you. [Intonation as reflection rather than advice]

Patient:Well that’s what you people always say!

Practitioner:But you’re not so sure.

Practitioner: [Decides to use information exchange. Becomes more directive] So getting well is your priority. Have you ever had a good talk about what happens in the heart after a heart attack?

Patient:Yes, sort of, but I don’t understand…

Note that the practitioner could have returned to the structure provided by the scaling question on a number of occasions: for example, So your fear of damaging your heart is stopping you taking more exercise. Were it not for this, what score would you give yourself for wanting to get more exercise? In this example, however, the scaling method was used as a springboard, not as a scaffold for the entire conversation. In other situations, it can be very useful to go back to the scale and the numbers.

You might wonder about the outcome of this kind of discussion. Where should it lead? It is unwise to generalize about this, because it depends on the unique needs of the individual. The point is that simply talking about the importance dimension can help to clarify things. It might or it might not lead to firm talk about change. The question, Why so high? invites the patient to spell out the reasons for change, which is more useful than their sitting listening to you doing that. It is best to follow the patient. If the discussion ends without action talk, simply summarize what has been said, offer whatever future support you can, and leave it at that. The aim of the consultation is not to get agreement or a decision to change, but to support the patient on the journey towards deciding what to do. Exploring importance is just that – exploration.

Strategy 3. Examine the pros and cons

Unlike Strategy 2, use of Strategy 3 does not have to be based on an explicit assessment of perceived importance. It is sometimes completely obvious that the importance of behavior change is an issue, and the only challenge is to decide what strategy to use to explore whether this importance can be increased at all. When it is preceded by a numerical assessment, this strategy is ideal when the score is around 5/10 on the scale. At 1/10, the patient might not perceive any costs associated with the behavior at all.

One aspect of the internal conflict (see Miller & Rollnick 2002) focuses on the costs and benefits of both staying the same and change. A conflict like that described in Table 5.1 might arise. Whichever way the person turns, there are costs and benefits associated with each option, change or no change. This has been termed a double approach–avoidance conflict.

| Someone facing the apparent need to change their diet might feel thus: | |

| No change | Change |

| COSTS | COSTS |

| Feel ugly and unattractive | Will have to think about what to eat all the time |

| Difficult to buy nice clothes | Will have to give up my favorite junk foods |

| Greater risk of heart disease and diabetes | Healthy food is often expensive |

| Can’t run around easily with the children | |

| BENEFITS | BENEFITS |

| Don’t have to think about what to eat, can eat with the family | Feel good about achieving it |

| Can eat the food I really like | May feel fitter and be healthier |

| If I lose weight, I will feel more attractive and confident, and be able to buy nice clothes | |

| Will be able to be more active | |

The different ways in which people experience this kind of conflict are not understood well enough. Certainly the experience embraces both psychological and social dimensions. In the addictions field, it has been well documented by Orford (1985). From excessive drinking, through gambling, to forms of sexual promiscuity, the intense battle between episodes of indulgence and restraint can render a person confused, elated, guilty, depressed, optimistic, and often enmeshed in conflict with others. It is therefore not surprising that alternatives to direct persuasion like motivational interviewing were first developed in the addictions field (see Miller 1983). The potential for conflict with a counselor is great. Within a few minutes, a patient’s mood can swing from defiance to remorse, from agreement about a problem to apparent denial of one.

In health care, we are not necessarily working with someone in the throes of a severe addictive problem, or what Orford (1985) called an excessive appetite. It could be a much more common dilemma. Mood swings might not be so severe and there is no reason to believe that overweight or even obese people walk around in a state of severe conflict. We simply do not know enough about how people facing behavior change feel. Clinical experience tells us that, among the people seen in healthcare settings where behavior change is discussed, the nature and extent of the conflict vary considerably. This variation occurs on a number of dimensions.

One of the most striking variations is in the breadth of the conflict. Some people are truly faced with the kind of multifaceted conflict described in Table 5.1. Others appear to be very uncertain about change, not because they are in conflict about the status quo, but because one major issue or perceived cost of change predominates over all else. An example would be a back pain sufferer who would very much like to become more active, but who feels reluctant to do some simple exercises because of a fear of causing further damage.

There is also variation in people’s awareness of the conflict, and whether they have spoken about it before. Smokers, it seems, are usually aware of the competing costs and benefits, excessive drinkers generally less so. Some patients have never spoken about their feelings and views before, and leave one feeling privileged to be hearing an account for the first time. Yet we all know patients for whom this is all familiar territory, almost to the point where they are ready and waiting for the practitioner to open up this little black box. They know the contents and they are ready with the answers that allow them to avoid consideration of change at this point in their lives.

An interesting dimension is the degree of emotional intensity involved. This varies across individuals and behaviors. Generalization would be unwise, as would a conclusion about whether it is better to encourage patients to explore these issues on an emotional or a cognitive level. Sometimes, the emotional expression of ambivalence can feel confusing for patients, and it is the articulation on a more cognitive level that seems clearer, more conscious and more helpful. The opposite can also be true. It is probably best to let the patient be one’s guide here, paying careful attention to resistance at all times. We have also found that as the patient makes a decision to change and ambivalence is resolved (at least temporarily), this is often accompanied by an emotional reaction. The person sighs deeply or even becomes upset. This can be most constructive, although the patient will obviously need commitment from the practitioner to look after him or her in an appropriate way.

Finally, there is often a distinction between short- and long-term consequences, with the former having a more powerful effect on decision-making than the latter.

A drink makes me feel better today although I will wake up tomorrow feeling rough.

Smoking feels good and seems to relax me now although I know it is dangerous to my health.

It feels better to be spontaneous and not to use condoms, although I know I am risking getting an infection at some point.

In summary, this aspect of ambivalence is not unlike an accountant’s balance sheet: rigid and rational, consistent in structure. It is an individual conflict about the personal value of change, often riddled with unique perceptions and contradictions. As such, there are few grounds for dogmatism and generalization about its content.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access