CHAPTER 5. Evidence-Based Practice

Vicki A. Keough

Every nurse can be proud to know that evidence-based practice (EBP) began with the founder of professional nursing practice, Florence Nightingale. 24,25 When she threw open the windows of the home hospitals during the Crimean war and insisted that nurses use clean linens to dress wounds and then started keeping a record of the results of her practice, evidence-based nursing practice was born. More than 100 years later, nurses are still asking important questions regarding their clinical practice. Nurses want to know that their interventions make a difference in patient outcomes. But what is evidence? What is quality evidence? What evidence is necessary before a practice can be changed? These questions continue to constitute much of the work of bedside nurses, nurse leaders, nurse researchers, and nurse scholars. Nurses, along with physicians and practitioners in the health care arena, are clearly still in the beginning stages of developing a practice based on evidence. 30

Some popular recent actions taken by nurses as a result of using an EBP model are the use of saline flushes instead of heparin flushes for peripheral intravenous (IV) lines; discontinuing the common practice of placing patients in Trendelenburg’s position for hypotension, highlighting the fact that volume, supine position, and keeping the head of the bed flat are the most beneficial interventions for patients with hypovolemia; and discontinuing the common practice of administering syrup of ipecac for patients coming to the emergency department (ED) with ingestions. 1.5. and 18.

When early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) for sepsis became the standard of care for all septic patients in EDs across the country, 6 the number of patients treated early for sepsis in the ED dramatically increased. This initiative came from nurses and physicians who asked the important question, Does EGDT truly decrease the mortality and morbidity of these patients?1 To effectively use evidence to guide practice, nurses need a very specialized set of skills. This chapter will provide a brief overview of how ED nurses can use EBP to enhance their individual and collective nursing practice and leadership skills.

WHAT IS EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE?

Definitions

One of the most prolific authors and leaders in the use of EBP is David Sackett from the University of Oxford, England. He describes EBP as “the conscious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.”29 Nurses are asking for research-based evidence to guide their practice. Evidence consists of both knowledge gained from clinical experience and knowledge gained from scientific studies. The blending of clinical experience and science provides a solid foundation from which care decisions can be made. 32 Many believe that evidence must be derived only from large, randomized control trials (RCTs) that use sophisticated research techniques to propose changes to practice. However, clinicians know that often these recommendations are either not useful or not practical for their patient population or for their clinical practice setting. This is where the art of nursing enters the arena of EPB. EPB is not just the review and critique of research and translation of these findings into practice, but the integration of all knowledge, clinical experience, and research findings to help nurses make the best decisions for their patients. 8.19.31. and 35. ED nurses are looking for evidence that demonstrates to patients and the public that they are receiving the best possible care within the best-designed health systems. Once the use of EBP is developed, it becomes a lifelong commitment to excellence and a commitment to a continual search for knowledge. If EBP is to be a lifelong commitment, then nurses must understand the importance of developing an organized and thoughtful approach to developing a practice based on evidence. There are several models that guide health care providers to developing EBP routines that will ensure best practices and optimal patient outcomes.

Evidence-Based Practice Models

Although there are many models for conducting EPB, four models will be presented in this section. The first is a model proposed by Sackett as a guideline for clinicians to use to implement EBP. 29 He proposed a five-step approach (Box 5-1). Sackett suggests that first clinicians must recognize specific problems within their practice and come up with a question that can be researched. Then they search the literature for any research or publications focusing on the question proposed. The clinicians will then conduct a critique of the literature and decide whether the findings would be applicable to their practice. Once a conclusion has been made based on the evaluation of the evidence and applicability to practice, a change in practice is implemented and then evaluated.

Box 5-1

S ackett’ s F ive-S tepApproach to C onducting E vidence-B ased P ractice29

1 Convert the need for clinically important information regarding practice decisions concerning diagnosis, prognosis, therapy and other health care issues into answerable questions.

2 Track down the best evidence to answer the question.

3 Critically appraise the evidence for validity and clinical applicability.

4 Integrate the appraisal with clinical expertise, and apply to practice.

5 Evaluate the results.

From Sackett DL: Evidence-based medicine, Semin Perinatol 21:3, 1997.

The University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics has developed a similar model; however, the Iowa model proposes a team approach to EBP (Figure 5-1). 35 The model suggests that a research question must come from problem “triggers.” These triggers can come from actual problems that have been identified through practice or from knowledge such as new research findings or new philosophies in health care. Once these problem triggers have been identified, a team decides whether or not the problem is a priority for the organization. If the team decides that this problem is a priority, the team will then review the current research and literature available on the topic, critique the research and literature, and if needed, develop a plan for a change in practice. This plan may include collection of further data, conducting research, designing new guidelines, or a modification of current guidelines. The team then determines whether or not the recommendations are appropriate for the current practice environment and if so, the change is implemented and evaluated. This model is designed to be used within an organizational type of environment, rather than a private practitioner–based environment, where the Sackett model may be more appropriate. An important aspect of the Iowa model is the recognized need for support staff and organizational support as an integral part of the model. For example, resources such as librarians, risk management information, financial data, and benchmarking data are integral to the success of this model.

|

| FIGURE 5-1 Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care. (From Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman VJ et al: The Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care, Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 13:497, 2001.) |

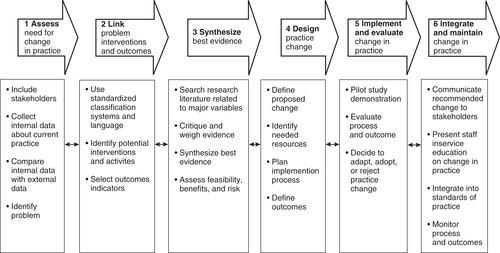

Rosswurm and Larrabee28 (Figure 5-2) developed a model for nurses using an approach based on theories of EBP, research utilization, standardized nursing language, and change theory. Step 1 of this model uses important concepts of change theory by assessing the need for change among stakeholders. Stakeholders can be patients, nurses, administrators, interdisciplinary team members, administrators, etc. The stakeholders then take control of the investigation and come together as a team to collect internal data about the current problem or practice to be challenged and compare the results of the internal data findings with published data. The team of stakeholders then clearly identifies the problem and makes a commitment to develop an evidence-based change. Step 2 links the problem with practice by using standard classification systems of Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) and Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), which allow nurses to link patient problems with nursing activities. The use of standardized language allows nurses to communicate more effectively, determines the effectiveness and cost of care, and helps to identify nursing resources. In step 3 the findings from the research and literature review are synthesized and critiqued. In step 4 a change in practice is designed. Step 5 focuses on implementing and evaluating the change in practice. Finally, step 6 involves integrating and maintaining change in practice by using a strategic approach to change. Having an open and ongoing relationship with the stakeholders, administrative support, and a clear dissemination of the findings of the research will enhance acceptance of the new protocol.

|

| FIGURE 5-2 Rosswurm and Larabee model. (From Rosswurm MA, Larrabee JH: A model for change to evidence-based practice, Image J Nurs Sch 31:317, 1999.) |

Finally, the ACE Star Model of Knowledge Transformation is a simplified model to help transform evidence into practice (Figure 5-3). 3.27. and 33. The value of this model is that it is very easy to remember and provides a practical approach to clinical practice. The ACE Star Model uses the five points of the star to represent the five stages of knowledge transformation. The top of the star represents knowledge discovery, followed by evidence synthesis, translation into practice recommendation, implementation into practice, and finally evaluation.

|

| FIGURE 5-3 Star Model of Evidence-Based Practice.Rights were not granted to include this figure in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book. (From Stevens KR: Systematic reviews: the heart of evidence-based practice, AACN Clin Issues 12:529, 2001.) |

FINDING THE EVIDENCE

What Is Evidence?

Once a clinical question or problem has been identified, whether by a nurse at the bedside or by a team within the institution, the identification and revelation of the evidence related to the problem is the next step in finding a solution to the problem. There has been much discussion about what type of information can be considered as evidence. Evidence can range from very scientific research publications such as RCTs, survey research, and cohort studies to case studies of interesting or unusual cases, expert opinions, or consensus conference recommendations. 12.26.29. and 36. RCTs are generally large experimental research studies designed to randomly assign patients to experimental and nonexperimental groups and compare the results of one form of treatment against a control group, which generally receives the current standard of care. The researchers then determine if the new experimental treatment is more effective than the current treatment. The “gold standard” for evidence used to guide practice is clearly RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. 29.32.33. and 38. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are types of research whereby the authors review multiple studies on a particular topic, separate the best research, critically analyze the research, and then make practice recommendations based on the findings. 17.33. and 38. These very carefully and systematically designed research trials have the greatest ability to inform clinicians about the best practices based on research. It is unrealistic to think that individual nurses or physicians have the skill, knowledge, or time to conduct systematic reviews of every question they have regarding their practice38; therefore systematic reviews or meta-analyses can be very useful to the health care provider. The Cochrane Collaboration is an international organization that was initiated in an effort to promote the accessibility of systematic reviews on the effects of health care interventions. 14 When a topic is chosen by the Cochrane Collaboration to undergo a systematic analysis, a rigorous standardized review process is undertaken by a group of experts on the topic. Once the review is completed, recommendations for practice are published. Cochrane reviews have been found to be more rigorous than either systematic reviews or meta-analyses published in peer-reviewed journals. 13 For more information on interpretation of systematic reviews, the journal Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine has published an excellent three-part guide for interpreting systematic reviews. 15.17. and 20.

Although RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses are the gold standard for providing evidence, many topics do not have an RCT, systematic review, or meta-analysis of the data available to help guide the clinician. Therefore it is important for the nurse to examine the available data on cohort studies, smaller experimental studies, qualitative studies, or case studies. Although it is clear that this type of research represents a less rigorous research design and is rated lower on the hierarchy of evidence, it is still very important information that will alert the nurse to trends or problems in current practice that need to be identified and examined. Most large trials result from a compilation of smaller studies that alert the scientists to the need for larger studies. Case studies are excellent means of highlighting a problem or issue that needs to be addressed by the health care community. A case study generally highlights an unusual or interesting case a practitioner has encountered. Although this is not considered scientific evidence, it may represent an interesting finding or a future trend in health care.

How to Search for the Evidence

Conducting a literature review takes time, a great deal of research knowledge, and mastery of the art of reviews. Many health care organizations employ research librarians who can be an invaluable resource to nurses conducting a search for evidence. The review must be conducted in an organized and systematic manner. The first step of the literature review is to formulate a question that provides clear direction for the literature search. For example, What is the best treatment for croup? can clearly be researched, as opposed to a question that is nebulous and difficult to search such as, How can patients live with croup?

Once the question has been formulated, a search can begin. The first step is to conduct a computer-generated search on the keywords involved in the topic. Common keywords can often be found within databases. Common databases used by nurse researchers include CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online), CANCERLIT (cancer literature), and PsycINFO (psychology information). 26. and 33.

When beginning to conduct a literature search, a nurse must first understand the difference between primary research and secondary sources. A simplified explanation of these two concepts is that primary research studies are studies published by the researchers who actually conducted the study. Secondary sources are authors who publish papers about research conducted by others. Because secondary sources generally report, critique, and evaluate the research of primary studies, they are providing their interpretation of the research and do not provide a detailed account of the original research. 26

Finding the best research or secondary sources that evaluate the research takes skill and practice. It is not good enough to simply find all the research and literature published on a specific topic; it is necessary to find “evidence that matters.” Evidence that matters refers to finding evidence that has implications to change a patient’s “overall prognosis and outcome and quality of life.”38 An acronym exemplifying this concept was coined in 1994 by Slawson and Shaughnessey—POEM, patient-oriented evidence that matters. 38 This concept was developed by a group of clinicians in England that publishes monthly findings of POEM research. They also have an active web site (http://www.infopoems.com) with monthly updates on current reviews. Before the evidence on a particular topic can be considered for a possible change in practice, the evidence has to meet the following three criteria (http://www.infopoems.com/index.cfm):

• It addresses a question that faces clinicians.

• It measures outcomes that clinicians and patients care about (i.e., symptoms, morbidity, quality of life, and mortality).

• It has the potential to change practice.

Searching for systematic reviews can also be conducted using a search of systematic review sources. Some of the sources that publish systematic reviews are listed in Table 5-1 and are available online, either free or with a yearly subscription. Journals can also be a rich source of systematic reviews, and a list of journals dedicated to publishing systematic reviews is included in Table 5-1. 22.26.33. and 38.

| Name | Web Address: http://www. |

|---|---|

| SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS | |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | cochrane.org |

| BMJ Evidence Center | clinicalevidence.com |

| DynaMed | dynamicmedical.com |

| First Consult | firstconsult.com |

| SUMSearch | sumsearch.uthscsa.edu |

| InfoRetriever | infopoems.com |

| TRIP Database | tripdatabase.com |

| The York Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) | crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb/ |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) | ahrq.gov |

| US Preventive Services Task Force | ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfab.htm |

| The Joanna Briggs Institute | joannabriggs.edu.au |

| The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) | oldhamilton.ca/phcs/ephpp/ReviewsPortal.asp |

| JOURNALS | |

| ACP Journal Club | acpjc.org |

| American Family Physician | aafp.org/afp |

| Bandolier | medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/journal.html |

| Evidence-Based Nursing | evidencebasednursing.com |

| The Journal of Family Practice | jfponline.org |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access